Another in the series on proletarian military policy, ‘L. Alfred’ speaks to the lessons of the Paris Commune in light of revelations of the French General Staff’s directives for the defense of Paris, Plan Z, in case of revolution.

‘The Paris Commune and the “Z” Plan’ by L. Alfred from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 9 No. 15. March 22, 1929.

The capitalist Governments are preparing not only for an imperialist war, but also for civil war against their own masses. In connection with the war preparations against the Soviet Union and with the swing to the Left of the working class the civil war preparations of the bourgeoisie have become particularly intense lately, because the imperialists know that their criminal attack on the workers’ State can let loose a storm of revolutionary indignation, that such a war means the development of civil war on an international scale. The tactic of suppressing “internal unrest” has become a burning problem in the military literature of the capitalist countries.

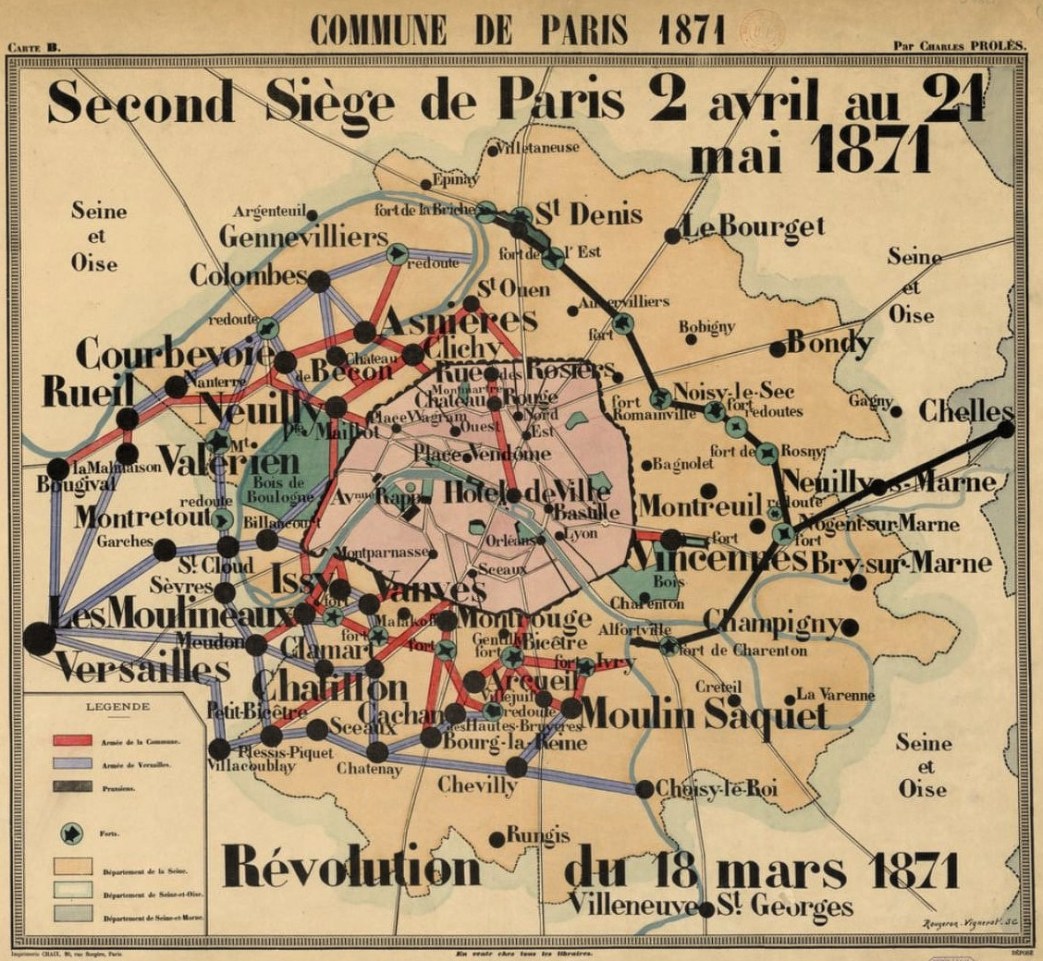

Plan “Z” (the plan of the French General Staff for the defence of Paris in the event of internal unrest) is a typical example of these civil war preparations of the bourgeoisie. This plan has been elaborated on the basis of the experiences connected with the suppression of the Paris Commune. Therefore, it will be opportune to study it a little more closely in connection with the anniversary of the Paris Commune, all the more so as the plan itself is not of a purely French character. According to the “Revue des Vivants”, plan “Z” provides in the event of serious disorders breaking out in Paris for the removal of the troops stationed in the city from the centre, and for their withdrawal to Versailles, in order to recapture Paris from outside, together with the garrisons drawn from the provinces, and to re-establish “law and order”.

As Messrs. Poincaré, Foch and Chiappe intend to adopt the same methods which were used by Thiers, MacMahon and Gallifet during the brutal suppression of the Paris Commune, an investigation of the experiences of the struggles of the Paris Commune will be of the utmost importance also to the workers. We wish to recall a few facts which can throw light on this tactic.

On March 18, 1871, Thiers attacked with the loyal govern- mental troops the Paris National Guard in order to disarm revolutionary Paris. The answer of the working population of Paris to this attack was a powerful revolutionary mass action, an armed insurrection. As the revolutionary ferment was beginning to spread to the governmental troops, and cases of refusal to obey orders and going over to the side of the rebels became more and more frequent, Thiers was compelled to leave Paris in a hurry with the troops which had remained loyal to the Government, and to retire to “peaceful” Versailles.

In Versailles, Thiers prepared a well-planned attack on Paris. He was most anxious to create a reliable army. For this purpose troops were drawn from the provinces which had not been in touch with revolutionary Paris. By agreement with Bismarck, the enemy of yesterday, 60,000 French war prisoners were released from Prussia and included into the army which was to attack Paris. When the concentration and organisation of this army of 130,000 men was complete, the Versailles Government began a regular war against Paris, using the following fighting methods: siege, bombardment, street fighting, and blood baths among the population.

The fathers of Plan “Z” want to use exactly the same methods in the event of serious unrest: if they do not succeed in nipping the revolutionary action of the masses in the bud, they want to withdraw their troops from Paris leaving the city for the time being in the hands of the rebels to concentrate their troops in Versailles and to recapture Paris from outside.

One should realise that the tactic of the plan “Z” is the most consistent civil war tactic of the bourgeoisie. Of course, the gentlemen of the French General Staff will do their utmost to nip in the bud any “internal unrest”. But if they have to do with a real revolutionary mass movement, if direct contact with the excited masses might produce vacillation, disintegration, a revolutionary mood, insubordination and going over to the side of the people, they prefer to withdraw, for the time being, their armed forces from the hotbed of revolution, in order to make use subsequently of tactics which will enable them to keep the armed forces in order and at a safe distance from the rebel population, so as to ensure their immunity from the revolutionary ferment. This can be best achieved by an attack from outside, when the troops act within the framework of big detachments, when they carry on a regular frontal attack on the hotbed of revolution, when they have a “subdued” and secure rear and can keep he necessary distance between the soldiers and the masses with the help of artillery and machine-gun fire. This was the tactic of Thiers, MacMahon and Gallifet. It is also now one of the fundamental rules in the theory and practice of all capitalist countries when it is a question of suppressing mass movements. It does not of course offer a guarantee for the absolute suppression of any insurrection. On the contrary, it cannot be successful if the insurgents know how to set against this tactic of insurrection-suppression a correct insurrection-tactic. For instance, even the victory of Thiers and his helpers over the Paris Commune was to a great extent due to the mistakes made by the Commune. Already on April 12, 1871, Marx wrote to Kugelman: “If they succumb it will be entirely due to their kind-heartedness.” One should have marched at once to Versailles after Vinoy and after him the reactionary section of the Paris National Guard had themselves cleared the ground. The right moment was missed out of conscientious scruples.

If the Commune had taken from the beginning the initiative of action, if it had assumed from the beginning a ruthless offensive, if it had been able to carry out a definite action among the regular forces of the government in order to disintegrate and disarm them or to draw them onto the side of the insurgents, the government would probably not have succeeded in escaping to Versailles with their armed forces. If this had partially succeeded, the Commune should have immediately made an attack on Versailles in order to give the quietus to the remainder of the counter-revolutionary troops which had been withdrawn from Paris.

Through the humaneness and passivity of the Commune the counter-revolution was given the respite which it needed. Up to April 3rd, i.e. for 16 days it was allowed to rally its forces undisturbed, before the Commune attempted its first undecisive attack. Naturally, the columns of the Paris Commune met now with the organised resistance of the Versaillers. As time went on, the correlation of forces took an unfavourable turn for the Commune because it could not possibly compete with the bourgeoisie in regard to army organisation. The technical forces required for such work were almost entirely in the camp of the bourgeoisie. Provided it could have at its disposal more or less docile cannon fodder, it was an easy matter for it to create a well organised army, whereas the organisation of the army was inevitably very slow on the side of the Commune. The strength of the Commune as of every mass insurrection, lay of course not in military organisation, but in the revolutionary activity and the heroic self-sacrifice of the masses, and last but not least, in the strong moral effect of the “spectre of revolution” on the enemy and his armed forces. Through their timorousness and passivity the leaders of the Commune missed the moment when the activity of the masses had reached its climax and when the enemy had not yet concentrated his forces. The greatest heroism in the defence of the barricades could not replace the offensive which should have taken place at the very beginning. In an armed insurrection, it is the first moments which decide the success of the struggle.

Another contributive factor to the suppression of the Paris Commune was the passivity of the provinces, especially of the peasantry. The Commune was certainly proclaimed in several towns (Lyons, Marseilles, St. Etienne, etc.), but even there it did not come to active struggle for and against the army, no efforts were made to prevent the concentration in Versailles of the provincial garrisons and of the troops released from the Prussian war prisoners’ camps.

If the future “internal unrest” feared by the originators of plan “Z” will be limited to Paris, if it is not accompanied by such “internal unrest” everywhere in the provinces and if the rebel masses do not assume from the beginning a ruthless offensive, so as to prevent the concentration of the armed forces of the counter-revolution, plan “Z” will have certainly every prospect of success.

Fortunately, not only the representatives of counter-revolution and reaction profit by the experiences of the class struggles, but also the oppressed revolutionary classes.

The revolutionary proletariat in all the countries believes in the struggle of the Paris Commune, it gathers courage and enthusiasm from the heroic example of the Paris barricade fighters and profits by their mistakes.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1929/v09n15-mar-22-1929-inprecor.pdf