Hook ends this 1934 essay with six framing proposals for a teachers’ movement.

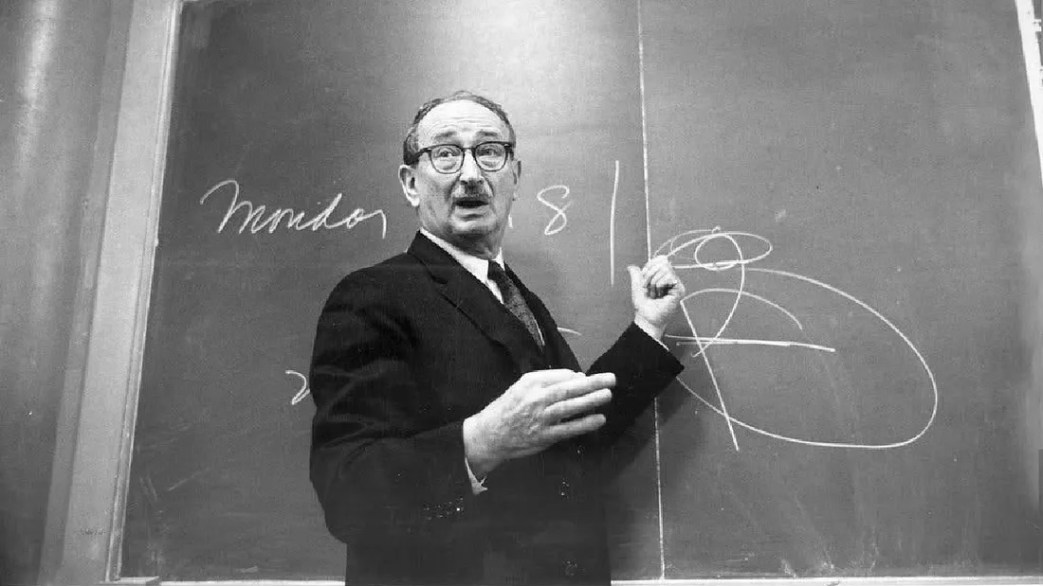

‘The Role of the Educator’ by Sidney Hook from Student Outlook (S.L.I.D.). Vol. 2 No. 5. May, 1934.

THE subject I wish to discuss here is one which is likely to become increasingly important with the accentuation of social conflicts in the next few years. It directly concerns the educational philosophy and activity of more than one million, one hundred thousand teachers in the nation. Indirectly it concerns the entire community which supports the teacher and which is in turn influenced in its pattern of thought and behavior by the instruction it receives. Briefly put, the question is: What is the creative and critical role of the educator in the world today? What are the limits and presuppositions of his legitimate criticism? Is he merely the servant of the community, paid to formulate and strengthen in the minds of the growing generation the values and prejudices of his social environment or is he to regard his teaching as a calling—as a calling to suggest, lead and guide in the creation of new social values?

If the teacher refuses to see this problem, the social order itself brings him face to face with it. Every age of social transition is an age of social criticism and our age is nothing if not transitional. The conflict of social principles, slogans and policies finds its echo in the class-room as everywhere else and the teacher is compelled to become self-conscious concerning the subject matter and method of instruction—especially in the cultural and social disciplines. If the teacher finds himself in a position where some of his views do not accord with those accepted by the group which holds political power in the community, he is likely to be confronted with the charge of being a propagandist and not an educator. He consequently must ask both for the sake of clarification and defence: what is education, how does it differ from propaganda, what is its relation to the school, and what is the role of the educator both as a teacher and a citizen?

These are extremely difficult questions and no one can offer complete answers to them. But a few things seem clear. To begin with, education in its widest meaning—the assimilation and extension of the culture of the group—is not co-extensive with schooling. There are societies in which educational processes go on as part of natural life and activity and in which there are no schools: and there are societies whose schools are not notorious for the amount or kind of educating they do.

Formal schooling on a large scale begins in general when two conditions have been fulfilled. First, where division of labor has been carried to a point at which the needs of production make it necessary to impart instruction in certain manual and verbal techniques: second, where class divisions in society give rise to different social values, and where the social process itself is incapable of enforcing homogeneity of interest, the school becomes one of the institutional agencies by which the values of the dominant class in the community become the dominant values in the community.

The function of the school as the overt instrument of education is therefore, two-fold: it gives instruction in certain knowledges and techniques, and more important, it consciously inculcates certain social and ethical values, attitudes and ideals so that they become a part of the unreflective, unconscious, unquestioned behavior of the members of the community. It is this latter function of education with which I am primarily concerned tonight. It is a function which has been recognized by every realistic social philosopher, statesman and politician from the days of antiquity down to the present. A few illustrations: Aristotle in the fifth book of his Politics (Chapt. 1X) wrote: “But of all things which contributes most to preserve the state is the education of your children for the state; for the most useful laws will be of no service if the citizens are not accustomed to and brought up in the principles of the constitution; of a democracy, if that is by law established, of an oligarchy, if that is.” Napoleon more than 2,000 years after was more forthright: “Of all political questions,” he proclaimed, “that of education is perhaps the most important. There cannot be a firmly established political state unless there is a teaching body with definitely recognized principles.” And to bring the record up to date—I select almost at random—a sentence from an address of a prominent Princeton educator to taxpayers in behalf of public education. “Taxpayers!” he said, “do not cut down school support because the levies on property seem to you to be too high;—remember that in the last analysis the public schools of this country are the most important safeguard of private property we have.”

Now I stress this particular function of education because I desire to locate the chief source of propaganda and creedal dogmatism in the system of public education. If my analysis is sound, the propagandist is no the social critic who examines the roots, conditions and consequences of dominant social ideals, evaluating them in the light of other possible social ideals—the propagandist is the teacher who accepts the status quo and its ideal rationalization as final and fixed, who seeks to make them part of the child’s unconscious by investing them with the sanctity of use and authority, and who teaches that existing institutions and ideals represent that which is invariant in human behavior so that to question them is to undermine the foundations of society and human life itself. It is a strange irony that when a teacher here or there submits to realistic analysis the fetishism of nationalism, success psychology and profit-incentive which pervade the social science curricula of the public school system, he is greeted with outraged cries of “Propagandist! Propagandist!” by those very conservatives who in season and out carry on unremitting propaganda for the dominant values of the dominant class.

But it might be retorted if the propaganda of entrenched conservatism is bad the propaganda of radical dogmas is just as bad. True enough—in the abstract. But if we keep our eye on the actual educational scene we discover that what is called radical propaganda is usually rigorous criticism of the accepted dogmas and not the imposition of new dogmas. Further it may even be argued that where new gospels are unintelligently presented as final truths by some uncritical minds, the fact that they clash with the accepted dogmas purveyed almost everywhere, gives them a certain educational value because they provoke the doubts, queries and difficulties out of which genuine thought arises. Where authorities fall out, critical intelligence gets its chance.

However, I am not one of those who believe that anything significant can be achieved by the inculcation of any kind of dogmas in the classroom. It seems to me that the methods of reaching a conclusion are more important in the long run than any particular conclusion reached. Genuine teaching is critical teaching, and critical teaching consists in the discovery and reasoned investigation of all relevant alternatives to ideals and plans of action under consideration. How much of our teaching is critical today? I venture to say very little, for the very process of challenging existing practices to show their credentials of validity is regarded by those most influential in the public educational system as incompatible with the function of the school in society.

In order to win the right to a free critical analysis of accepted values it becomes necessary to challenge the dogma that the school must be the servant of society.

First of all, society is not a homogeneous unit but is torn by a conflict of interests, groups and classes. Loyalty to society, then, means loyalty to whom? The schools are supported,—when they are—out of the social wealth created by the collective producers of the country. Loyalty to this group may be incompatible with loyalty to a political apparatus or a state machine or an administrative bureaucracy which identifies its own class good with the good of the community. Secondly, granted that we know what we mean by society, to serve society does not mean to be a servant of society. Socrates, Bruno, Karl Marx can claim—certainly with justification—that they served society better than those who, fortified by the doctrine that the educator must serve existing society, prevented and persecuted these men in their educational activities. The educator serves society truly by making a critical survey of social realities and social ideals and then honestly and courageously defending any conclusion he may reach.

This last statement runs counter to the assumption of some educators who call themselves liberal and who hold that the educator can and must make critical surveys but that he must not reach—or if he reaches, he must not state—any positive conclusions. Otherwise, so they say, he runs the risk of being dogmatic, of holding views that may not stand up when all the facts come in. Now the truth of the matter is that all the facts can never come in and there is a risk attached to believing or asserting anything on the weight of probabilities. But is it not queer that although logically the same thing is true in science, these educators do not caution the scientists to refrain from drawing conclusions after examining the evidence? Is it not clear that the real point at issue flows from the nature of the subject matter of social thinking, from the fact that since the social sciences are not genuinely experimental the same consensus of opinion cannot be arrived at as in the physical sciences, so that there is always the danger that the considered judgment of the educator will strike at a dogma which some vested interest is striving to perpetuate? Certainly, there is this danger but only one who regards the educator as a social and political eunuch will desire that he avoid it. In the last analysis intellectual integrity consists in the willingness to take a position after the critical analysis has been made. The position does not have to be advanced as the absolute truth and on some matters the evidence may call for suspended judgment. But this does not in any way justify denying to the teacher and educator the right enjoyed by every other professional worker to express freely and publicly his conclusions no matter whom they affect provided he is prepared to argue critically for them. In fact if this right is denied, the teacher loses his professional status in two different ways. Insofar as the teacher is a specialist in any subject-matter, he loses the respect of the community which will distrust his findings if it suspects that he has been guided or hampered by extraneous considerations in arriving at them. Insofar as he is a teacher of the youth who naturally look to him for leadership and inspiration—what respect can they have for him if they believe that he is free to hold and express only those views which are approved by his superiors?

If my point is well-taken that effective teaching means effective criticism and the class-room right to engage in it, it will not be difficult to show that the duties of the teacher are intertwined with his duties as an intellectual worker and citizen. It requires but a superficial knowledge of what is happening to the educational system of the country to convince him that the conditions of effective teaching, security of tenure, salary and working conditions, together with the health and welfare of large numbers of the young, are rapidly being undermined by the consequences of the existing economic system. No matter how sound his educational philosophy is he will never be able to apply it so long as the continuance of educational services is a function of the business cycle, so long as he cannot control his own vocational destinies by well organized teachers unions, so long as the shadows of war, poverty and fascism make it impossible to turn school into society and society into school.

Space does not permit me to develop these ideas at length but I wish to state programmatically my own conception of the function of the teacher both as a professional worker and a citizen. Since these are days in which every proposal is made in points, I wish to offer the following six point program for a teachers’ movement—I offer them not as dogmas but to provoke the critical discussion which precedes intelligent action.

1. The primary cause of the contemporary chaos in economic, social and political life is private ownership and control of the instruments of production, from which arise recurrent crises, increasing misery of the great masses of the people, insecurity, unemployment, imperialism and war.

2. The specific economic disabilities from which the educational system of our country suffers—retrenchment all along the line, discontinuance of educational services, overcrowding in class-rooms—as well as the pressure under which the teacher labors to make his educational activity subserve the cults of nationalism, political conformity and cultural orthodoxy are directly traceable to the organic processes of capitalist production and the needs of those classes who wield the dominant political power within.

3. Since under the present order the conditions of effective teaching are beyond the control of the teachers, they must organize their energies for a fundamental transformation of the social system.

4. The economic and cultural difficulties of all other producing groups in the country—the workers, farmers and professionals—flow from the same basic factors which are at the source of the teachers’ predicament.

5. The teachers of the country must therefore align themselves with the workers, farmers and professionals in a common struggle for a classless society.

6. This struggle must inevitably assume a political form; the immediate goal of such a movement must be the establishment of a government, of, by and for producers to initiate and enforce the necessary measures toward a classless society.

Going through a series of names in the 1930s starting with Revolt, then Student Outlook, then New Frontiers, and finally Industrial Democracy these were the publications of the Socialist Party-allied National Student League for Industrial Democracy. The journal’s changes in part reflected the shifting organizations of the larger student movement.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/industrial-democracy_1934-05_2_5/industrial-democracy_1934-05_2_5.pdf