How barbarous a country is the United States? It is this barbarous. Apologies ahead of time for the language in this justly famous expose of the hellacious convict-lease labor camps producing toxic turpentine in Florida’s swamps.

‘Turpentine: Impressions of the Convicts Camps of Florida’ by Marc N. Goodnow from International Socialist Review. Vol. 15 No. 12. June, 1915.

THE huge pine forest, its cool shadows interlacing across a ground growth of palmetto stubble, afforded a tranquil retreat to a lonely wayfarer that Sunday morning. The pungent aroma of fresh resin was exhilarating. Palmetto leaves playing against each other in the light spring breeze and a distant, mournful baying of hounds were the only sounds that broke the stillness.

Suddenly the baying of hounds grew near and raucous; every tree became a sounding-board—a voice in itself. Nearer and nearer came a great scuffling and crunching. A man plowed his way through the mat of dead leaves, grass and pine needles—a Negro running head-long, his face burnished with sweat, casting furtive glances over his shoulder. On his body was the flannel garb of a convict.

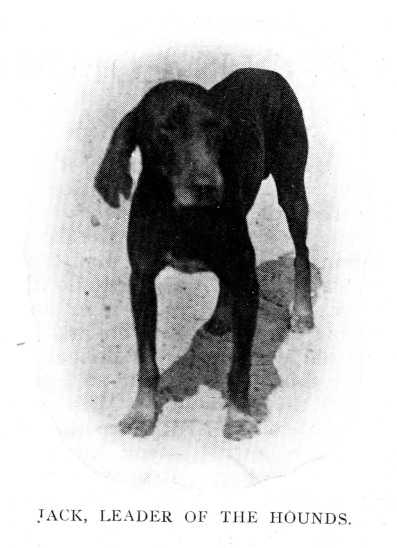

For a moment the swift impression of witnessing an escape flashed through the spectator’s brain, but there was not the slightest chance of that! The dogs were beating through the palmetto growth like an avalanche down a mountain side—six of them, their dilated nostrils scenting the ground every few leaps, tongues hanging dry from their vicious mouths.

Great drops of sweat flooded the receding forehead of the hunted black; sweat glued his striped shirt to his muscle-taut body; to one foot clung a coarse shoe; his trousers were torn and frayed from contact with sharp palmetto leaves and wet and sticky with the ooze of a nearby swamp.

He swept one last look across his shoulder. Then, with an agility surprising to see in a body seemingly spent from long pursuit, the black arms shot up, the legs came up under the thick trunk, and the Negro in one giant, primitive spring, had landed six or seven feet up the stock of a virgin pine—straddling it as a gorilla would a grapevine—and “shinned” on up to a place well beyond the reach of the dogs.

Almost in the same instant a hound pup sprang even higher up the tree and fell back savagely, not once taking his hungry, fire-shot eyes from the crouching form above. In another instant the entire canine detachment had surrounded the tree, baying furiously.

A shout arose as three husky young men, mounted upon horses and wearing large black slouch hats, with long barreled pistols protruding from their hip pockets, swept up in full pace. They dismounted, leashed the dogs, and led them back through the woods. When they had reached a safe distance, the black, with the hunted look still on his face, crept down and shambled after.

It was only the usual Sunday morning practice, the rehearsal of the hounds—professional convict-trailers—from a nearby turpentine camp manned by forty Negro convicts, sold body, mind and soul, to the distiller of turpentine for the sum of $400 apiece per annum. And this usual Sunday morning rehearsal took place, not as you might suppose, in South America or Zanzibar, or Mexico, but in the state of Florida!

Of course, dogs must needs be kept in practice; disuse might dull the keenness of their sense of smell. It is a practical application of the theory that men and animals alike lose the talents which they do not improve. A “cracking” good hound dog in a convict camp is a much more fit object for the pride of officials than the black man who dips pitch or scrapes resin and toils in palmetto scrubs and swamps, wet to his shoulders and ill with pneumonia, rheumatism or consumption!

There is small fear that the Negro who plays the role of escaped convict will escape. His trail is only an hour or two cold, so the hounds pick it up easily and follow rapidly. Yet, who knows but that the hunted creature on that balmy Sunday morning, shot forward blindly in a mad desire to escape the punishment meted out to him in the midst of a wilderness of pine forest and infested swamps, might not have been bent actually upon no “make-believe” escape? At any rate, the officers and guards did not inquire after the health of the convict at the end of the chase; they only patted the dogs’ heaving ribs and stroked their heads in appreciation.

This particular chase I witnessed two years ago. It was then a weekly custom in each of the thirty-one convict camps of the state of Florida. Since then some of these camps have gone out of existence and the state has made a beginning in humane consideration of its prisoners. But other camps were given a new lease of life and are still running. While the light of a new day is dawning in the penology of Florida, the conditions now to be described and the spirit back of them, still play a dominant part in the treatment of convicts not only in Florida, but throughout a large portion of the South.

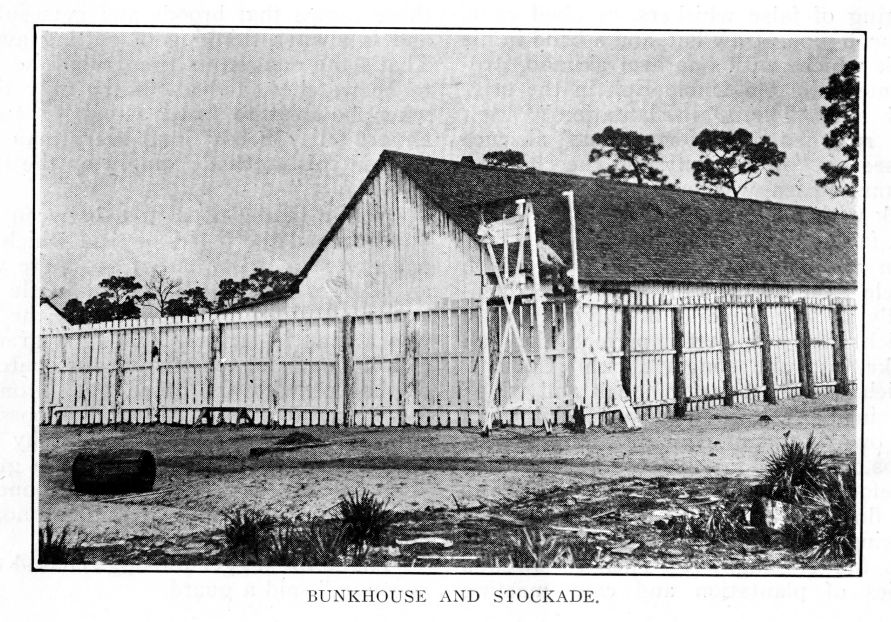

Along the homeward trail through the pine woods that Sunday morning, horses, riders, hounds and Negro lengthened out in caravan-like twists. A mile’s tramp brought the party to a clump of whitewashed, rough board buildings squatted in the white sand close to a railroad. From a distance the largest building had the appearance of a warehouse or a stable surrounded by a high board fence or stockade. It was a story and a half high, thrice as long as its width, with windows along the sides heavily barred.

At two opposite corners of the high stockade were rudely constructed platforms sheltered by as rude a roof of pine boards. Beneath these shelters sat two young men lazily smoking cigarettes, their long-barreled pistols beside them.

Near the railroad was the camp store, or commissary. Inside another enclosure was a small, one-story shack from one end of which a cloud of smoke issuing, proclaimed the kitchen. Farther back in the same enclosure was another shack, open on three sides, and a pig pen.

In the middle of the sandy yard stood a well, fed from surface water and the excess of the bayou more than a mile away. There were no trees, no grass, no shade of any kind, nothing but hot white sand and a few stumps.

A lean, swarthy man of thirty-five years, wearing the ubiquitous black slouch hat, and known by the official title of Captain, welcomed me as a visitor, and announced that dinner would be ready shortly. Until then we might inspect the camp.

Working Squads.

The convicts are worked in three or four squads, each in charge of one or two guards and several dogs. One squad may box virgin trees, another dip fresh pine pitch, another scrape third-year trees, another pull fourth-year trees, and another back-box older trees that are sufficiently large to yield still more resin.

The work is so arranged that the squads arrive at a certain stage of their rounds on certain days of the week. The entire territory is covered between early Monday morning and Friday night or Saturday noon. But it is constant and heavy work. A soft pitch is gathered from the open face of the blazed tree from March to October. From October to March, the gum must be scraped or pulled from the tree. The still, in which the gum and pitch are distilled into spirits of turpentine, is located near the camp and is kept supplied by teamsters and their wagons. A barrel of soft pitch produces approximately ten gallons of spirits of turpentine. In a single charge of ten barrels of scrapings, or gum, there are about six barrels of resin and two barrels of spirits. The stills run two charges a day ordinarily, and produce from 100 to 120 gallons of turpentine in one charge.

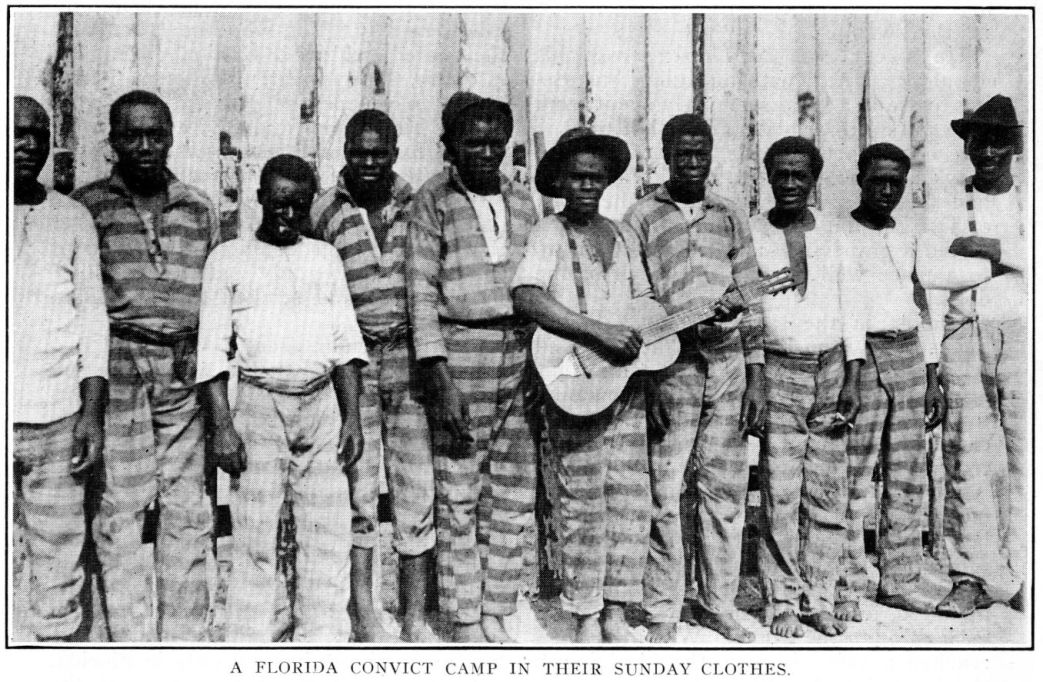

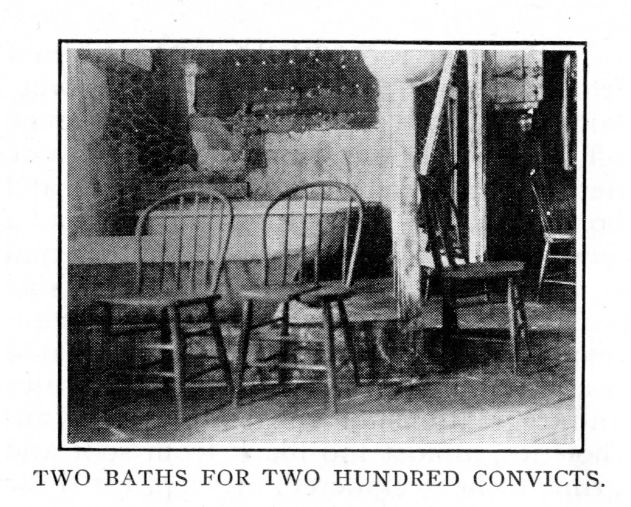

“Sunday mornin’ the men spend in cleanin’ up, takin’ a bath, and changin’ clothes,” drawled the captain, as the big gate of the stockade swung open and a growing pile of soiled, striped flannel garments became conspicuous. Here was the unique sight of a score of nude convicts, exchanging soiled garments for fresher ones. Their glistening bodies were burnished bronze in the strong sunlight and their huge, knotted muscles played under the skin like great cables.

“The odor won’t be very pleasant,” added the captain as he led the way to the bunkhouse and mess-room, “but it is more the smell of disinfectant than anything else.”

The interior of the building was even more crude as a place in which to live than the exterior as a means of shelter. No attempt had been made to “finish” the building, as craftsmen would say; that is, to ceil, or plaster, or remove the bare effect of finished rafters and boards. A barricade of heavy timbers set vertically from floor to roof formed a partition between mess-room and sleeping quarters. Next to the only door of the building, was a small cage built of heavy timbers and furnished with a small heating stove and a chair for the guard who kept night watch over the forty sleeping convicts.

Two zinc-covered tables to the right of the entrance formed the dining-room tables; boxes and broken chairs formed the seats. In a corner close by stood a sink and basin where the dishes were washed. Only dishes, pans, and spoons are used inside this stockade. There are no knives or forks (except for warden and guards). Fingers were made first; besides, knives and forks are much too ugly as weapons in a quarrel.

In the same room, at the corner farthest from the door, were two cracked porcelain-lined tubs set in a space not screened off but merely surrounded by torn wire netting. Several more broken chairs and boxes and a heating stove within a wooden pen, completed the furniture and equipment of the mess-room. On one wall hung an illumination of the ten commandments, and several illustrated psalms. On another wall hung the rules and regulations of the state prison authorities, almost too black from soot and grime to be deciphered. Except for these wall decorations, there was no evidence anywhere of any reading matter.

The bunk-room was a long, low compartment filled with iron beds supporting filthy mattresses. The floor was bare and reasonably clean, and the entire interior smelled strongly of a mixture of formaldehdye and other disinfectants.

“The beds are a bit old,” was the explanation volunteered, “but we’ve made a requisition for new ones. We disinfect every other day and scrub the floor every morning. Sunday morning, of course, the men always take their time about things.”

In the mess-room the prisoners were singing and laughing and telling jokes. In one corner a black figure was just emerging from his “tub;” in another, the rattle of tin and granite dishes told of preparations for dinner.

The Vaudeville Troupe.

“Where’s Charlie Jackson?” called the Captain, and two barefooted men shambled off to find Jackson. Presently the most genial smile one ever saw peered around the jamb of the door and a slender young Negro of thirty years shuffled into the room.

“Charlie,” said the Captain, “let’s have a little harmonizin.’

“Yassah, boss,” he smiled, and forthwith assembled his troupe of vaudeville entertainers. Charlie disappeared for a moment and returned in his theatrical rigging of false whiskers, crooked cane, corncob pipe, straw hat, and a bend in his back which, with one arm akimbo, proclaimed him old Uncle Eph in the original skit “The Old Plantation.” Eph had returned after forty years’ absence to see his “ole mammy and the chillun.” Mammy Liza was enacted by a young buck with a bandana tied about his head and falling over his shoulders.

In the midst of this skit, in which Uncle Eph referred to his children generally as “big hunks o’ midnight,” and in which each was letter perfect, they all broke into the song, “Pickin’ Cotton,” which was the cue for “buck and wing” dancing. Each of the seven indulged in his own brand of dancing and executed steps one never saw before–in shoes and barefoot. Some one pitched a quarter to the floor and the antics of the dancer in picking up the coin threw the observers into fits of laughter. Then followed a series of plantation and camp-meeting songs and hymns by another set of singers curiously enough, the most vicious men in the camp, it was said.

“Almost every night it’s just like this,” said a guard. “They go over this stuff time and again. They gave a minstrel show last Christmas and made quite a lot of money from the visitors.”

“Don’t they do it largely to forget they are here?”

“All their singing and dancing wouldn’t make them forget that,” answered the guard with a significant glance. “But after the first three or four months, the tragedy wears off and they get to be like the fellows who have been here for years. It’s the man who first comes to one of these camps that broods and gets sullen and is always thinking of getting away. That’s the dangerous time, when he has to be watched, and about the only time when he tries to break camp. I could almost tell you how long every man has been in this stockade simply by the look on his face.”

Outside in the open area between the building and the fence, beyond which no one except a trusty might go, there was an odor of meat boiling in a kettle set over a small fire. Hovering over the fire was a man in stripes, holding a granite dish in one hand and stirring the contents of the pot with the other, and intoning something about “dat ole swamp ‘possum an’ yam tater.” And then as if by the magic of his words, he drew out a great yellow potato as well as the leg bone of a ‘possum, truly the greatest gastronomic delight of the Negro.

“That’s the n***r the dogs chased this morning,” said a guard.

Certainly he was enjoying himself now, however great the strain of the morning might have been.

In another corner of the yard, a dozen men were engaged in shaping and smoothing long pine poles for use in pitch gathering. Charlie Jackson had come away from his vaudeville within and was now laboriously turning the crank of a grindstone while one of his co-workers sharpened the end of a three-cornered file for use in the woods.

All the men were in their barefeet; feet, too, that were swelled and misshapen almost beyond recognition. They were spread out, broken down, cut, gouged, blistered and scratched; and the ‘nails of many of their toes were gone. It is hard to imagine what comfort such feet will ever find in the shoes of civilized society when release from prison conditions finally comes.

“Niggah’s dat fust comes heah,” said Charlie’s mate at the grindstone, “what ain’t use’ to bein’ on dey feet, gits fagged easy an’ hit mek dey feet swell up sumptin’ awful, boss. Dat’s why dey all goes barefoot in de stockade an’ roun’ camp. Dey shoes ain’t big enough foh dey feet. Mine doan swell no mo.'”

One could see that easily enough; they had already reached their limit.

Doodle’s Kitchen

Few American housewives would put up with such conditions as were found in Doodle’s kitchen, to which the captain and visitor and several guards now went for dinner. Doodle was a wiry little cook with a genial and continual smile, but he had not been schooled in domestic science. On one corner of this unique culinary establishment was a rude stove of bricks with a metal strip across the top. In another corner was a barrel of flour and a bread board; and finally, a chest containing supplies.

There was no flooring; the kitchen was carpeted only with a soft layer of sand. Through the open door strolled at will two huge Berkshire hogs and any of the six or seven dogs that happened to smell something they liked. The dining-room adjoined the front of the kitchen.

The meal consisted of stewed tomatoes, boiled rice with tomatoes, soggy cornbread, leaden biscuits and fried chipped beef. Cream for coffee came from condensed milk cans, fly-specked and rusty. The knives and forks were encrusted with a thick coating of rust which made contact with one’s teeth the equivalent of excruciating toothache and produced a form of nausea. The beef was well cooked, though it was too strongly seasoned with sand to make an appropriate viand for a Broadway cafe.

The state report catalogues the following as the diet of the prisoners:

“Good bacon, meal, flour, grits, rice, peas, white potatoes, onions, beans, syrup, coffee, vegetables. In addition, prisoners are served twice a week with fresh beef, pork, or fish for a change. On Thanksgiving, Christmas and July 4, when there is no work, they have chicken, turkey, pork, pies, cakes and all kinds of fruits.”

A tempting menu. But this is what the convicts tell you they get: “Three biscuits and a piece of meat for breakfast; biscuits or cornbread and meat for dinner in the woods; biscuits, meat and beans for supper. The meat is generally salt pork, sometimes bacon or fresh pork. And beans till you can’t rest.”

Being able, however, to catch racoons or opossums and to buy the big sweet potatoes or yams, the convicts often feast in the stockade at no expense to the lessee.

At Baseball

When two o’clock came there were twenty men in line at the gate ready to file out for a game of baseball. The yard man counted each one as he came through and checked off his name on a list. Two guards carrying rifles walked just ahead.

The game—there were six innings of it—was uproarious. It was crude, of course, but full of life, each side bantering and joking with the other over an error or a “strike-out.” And the pitchers invariably yelled that old cry of “judgment!” after each pitched ball.

Only the catcher and first baseman wore gloves. These were fashioned from hemp sacking, stuffed with straw and rags. The rough diamond was covered with palmetto roots and stubble; yet most of the men played in their bare feet, and they were fleet runners, too. But they were ready to quit at the end of the sixth inning, and marched back to the stockade under guard.

After the game I shared my seat on a log with a guard. “Jack” and “Scrap,” two of the “dogs of war,” followed and flopped down before us.

“They’re lazy looking pups,” I suggested.

“Yes,” he smiled, “till they get on the trail.”

“Then its serious business, eh?”

“I should reckon. They don’t allow no one to mess around ’em. They’re tired now; had a two-mile chase this mornin’.”

“Would they have torn up that black this morning if they had gotten him?”

“They sure would. We train most of them just to follow the scent and keep a barkin’ after they’ve treed him; but Scrap there, goes right after his man. The other dogs would jump in, too, if Scrap got the fellow before he shinned a tree.”

“But Scrap’s only a cur dog,” he continued after a pause. “Can’t keep full bred blood-hounds in this country; they get sick and die. AH our pack here is nothin’ but plain cur dogs. But they follow a scent as well as a blood-hound. Scrap got after a white fellow just yesterday and was chewing up his leg when I got to him.”

He spat a stream of tobacco juice beyond the dog’s body and stroked Scrap’s head reflectively:

“If I had my choice,” he added, “between dogs and guns, I’d take the dogs every time. There’d be twice as many escapes round here if there wasn’t any dogs.”

“And do the dogs always track down the fugitive?”

“They do if there is any scent at all. When the nine men broke out of the back end of the stockade last year while the guard—he was hard of hearing—went out to ring the night bell, they got about three hours start before we knew they were gone. Three of our picked dogs chased them for miles. They never were captured. The dogs died a few days later from the effects of the chase; too much exertion, I s’pose. Two men got out later, but the dogs treed them.”

From the total of 1,421 state prisoners “on hand” in Florida, January 1, 1912, 516 of whom had been committed the previous year, there were in all 96 escapes. Just 47 of this number were captured and returned. The company which leased them lost the $400 invested in each escaped convict.

Seven convicts died in this camp in a single year from diseases contracted from standing or working in water around their waists at all seasons of the year. There were no funeral services. The local carpenter throws together a rude coffin of pine boards; the black, inert hulk is rolled into a blanket, dropped in the box, nailed up and carted to the burying-ground—mourned, perhaps, by a disgraced mammy who may have raised the future governor of a state.

July and August, the rainy season in Florida, are the worst months of the year for ague, chills, fever, pneumonia and the like. Then it rains almost every day and the water floods the country.

“Dat’s de time when it gits yo,” said a convict in a whisper. “Mah Gawd, men, hit’s sho’ awful, standin’ in watah an’ runnin’ all day long in the wet grass up to yo’ waist. Why, man, Ah’s got a lump in mah chist right now as big as yo’ fist. Every man in this heah camp has got sumpin’ the matter of him.”

In 1910, Governor Gilchrist considered twenty deaths among 1,781 prisoners a low rate, because “so many are diseased before entering the camps.” He also declared “at least 75 per cent of the colored prisoners have syphilis in some of its stages.”

Few men are sent to these camps on short terms. It isn’t profitable to the sublessees to have them, for the cost of keeping a prisoner is figured at $2 a day, and constant changing increases the cost and interferes with the work. But even though it pays $400 a year for each convict, in addition to nearly $750 a year for his upkeep, the camp mentioned here made a profit of $25,000 on distilled turpentine and resin in 1912. If there is any loss in earnings from the year to year, it is generally the pine trees that are at fault and not the men who work under the task system. Their stint for the day or week is about the same, rain or shine, sick or well. The treatment, of course, depends very largely upon the captain, who sometimes has an interest in the business.

Keeping Order

My host, the captain, was a slender, wiry fellow who, one could see at a glance, was accustomed to overseeing Negroes. He showed a certain quiet reserve of manner, but an unmistakable force. There was a catlike stealthiness, springiness, about him even in moments of repose, that gave one a kind of wonder, when he discussed the treatment of prisoners.

“‘Tisn’t necessary to handle the men roughly, except when they get incorrigible or commit some act that requires punishment,” he said with a typical drawl. “Yes, we use a strap; but not very much. I don’t have much trouble.”

My mind reverted to the picture which the tales of people who lived close to this camp had conjured up for me, of Negroes yelling for mercy while being flogged: “Oh, Captain , I’ll be good. I’ll be good, Cap’n. Please don’t beat me no more, Cap’n.”

No one who has seen that strap—a heavy leather lash four inches wide, with a thick handle–could have any difficulty in picturing a prisoner prone upon the floor receiving full punishment at the hands of a broad-shouldered guard of even from the lithe, wiry captain himself.

“Of course,” observed the captain, “there are some things about a convict camp that are best not talked about.”

In confidence he told of an instance just that week in which a Negro had refused to work. The captain was on the point of shooting the fellow for insubordination, he said, but changed his mind and only knocked him down three times with the butt of his revolver, as the prisoner rushed at him. Refusal to work, induced frequently by other things than sheer laziness, forms the basis for a large part of the punishment.

A trusty at the turpentine still seemed to voice the inevitability of the thing when he said: “We all gets pretty good treatment, boss. ‘Cose, Cap’n, he drives pretty hard, an’ a man gits sick oncet in awhile, boss; but then that doan mek no difference ‘roun’ heah—dey all jes works ’bout de same, nohow.”

All prisoners are worked on the task system, and if they finish their work on Friday evening or early Saturday morning, they have the balance of the week in which to rest. This system, inspectors say, has been the means of getting good work out of the men without punishment. But there are many camps where there is entirely too much punishment, where the wardens and guards are not at all suited to their positions. Thus does the state delegate to thirty or more wardens or captains and six or seven times as many guards, the very important feature of punishing its prisoners.

The captain draws $150 a month; the guard draws $25 a month—$35 if he has a horse. The life they are compelled to lead drives them to excessive drinking as well as to gambling and other questionable practices. One of these captains was a part owner of the still and business, and allowed the prisoners to work overtime, for which they were paid. Then, because of his fondness for gambling, he compelled the prisoners to gamble with him, and in that way won back all the overtime he had paid out. These practices exist despite the fact that the warden or captain is an officer of the law, as much as is a county sheriff.

In addition, there is the “private pardon” system, operated by a firm of lawyers who for $25 will start proceedings to secure a pardon. It is always the great hope of the man who goes to prison; he thinks he is innocent; he is sure his case was not presented properly in the first place. Perhaps the case is started, applications filed and other legal overtures made. Then, another payment of $25 is necessary to carry the proceedings on farther. There is another period of overtime work or appeals to relatives by mail and the second installment is sent on.

Sometimes a pardon does come; that is why the scheme is so well and faithfully patronized by men who wear the stripes. But what chance is there for the average prisoner? Of the 1,821 prisoners in 1911, the state report shows that only 37 were pardoned. Of a total of 1,928 prisoners during 1912, 60 were pardoned.

When you cut or burn your finger and run to the medicine cabinet for a bottle of spirits of turpentine, you seldom stop to think of the way in which this medicine is gathered; how much more of pain it involves than the pain which you seek to allay by its use; what bodily and mental travail; what cost in human life ; what degradation of a great and beautiful state merely for the sake of a few paltry dollars—the continuation, in fact, of a slavery even blacker in its sin than that before the war.

At the time of my visit to this camp, 1,800 or more convicts were leased by the state of Florida to one company—the Florida Pine Company—for the sum of $323.84 per convict annually and in turn subleased by the company to the individual turpentine distillers operating the 31 convict camps of the state for the sum of $400 a year apiece. Thus the Florida Pine Company was collecting the tidy little sum of about $76 per annum per man upon the labor of between 1,400 and 1800 convicts—a total of perhaps $125,000 a year This company paid to the state in 1912 for the use of convicts $307,116.48. (during the thirty-two years in which the convict has been leased by the state, the state has received a total of $2,722,620.14.) The arrangement was so satisfactory and profitable to both parties that the lease was renewed in 1909 for a period of four more years; and on January 1, 1914, a number of leases were renewed for two years.

But what does the convict get out of it?

Nothing but a whitewashed stockade, work the year round in all kinds of fever and weather, punishment with a leather strap for infraction of rules or lagging at work, no energy left for overtime work even if he were paid for it, and no money for those who may be dependent upon him.

This is what Florida— and in greater or lesser degree a score of other states—gives these men in return for the more than $300,000 worth of labor they annually produce.

This is the opinion also of the Commissioner of Agriculture, in whose department convict labor is placed. He asks in his report: “What has the state done for the convict?” and answers his own question by saying: “Nothing. But we have taken the money from his labor and have appropriated and used the same for every known purpose except one—the betterment of his unfortunate condition.”

Until 1914 the state owned not a single prison building, stockade, hospital, or any other equipment. All these belonged to the lessee or sublessee companies. There is a system of state inspection, which seems never to have had any effect upon the type of buildings, or to have been used for any real reform in prison practice. The whole idea of the camp’s local government is to get out the full run of turpentine or lumber; the previous record is always before its eyes.

As thousands of pine trees lose their productiveness each year and are cut down for lumber, it is no longer profitable to operate some of these camps. Several went out of existence when the four year lease expired on January 1, 1914. Scores of convicts have since been turned back to the state or released for some other work.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n12-jun-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf