Sweden’s big, vibrant Socialist then Communist youth movement is the subject of this valuable report from Hjalmar Vicksten. Tracing the growth from its organizational origins in 1903, its role as center of the country’s left Socialist trends, and it emergence as one of the largest, with 25,000 members, constituents of the new Young Communist International.

‘Young Sweden’ Hjalmar Vicksten from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 11-12. June-July, 1920.

Besides the Left Social Democratic Party there is in Sweden only one other organisation connected with the Communist International, it is “the Social Democratic Union of Youth”. In the course of its existence this association has played a conspicuous part in the Swedish Labour movement: at first as vanguard of Socialistic propaganda in general, then as centre, which united all the opposition elements of the old Social Democracy, and lastly, as the largest and most truly Communistic organisation. Less than a year has elapsed since the Union of Youth fully adopted a Communist programme and tactics and joined the Third International. The latter decision was adopted by the congress of the Left Socialist Party although not with the same unanimity as at the congress of the Youth. For there is in the Party a minority, pretty considerable so far, which does not recognise Communism, and this minority includes various elements like the parliamentarian-inclined representatives of the Bennerstrom current, and the “humanists”, who dominate the majority of the parliamentary faction, with the majority leader Lindhagen, etc. The Union of Youth on the contrary, which since its final secession from the “right” Socialist Party has become the framework of the “left” Socialist movement, and without whose participation no new party or party publication could have appeared these last three years, is unanimously in favour of the new orientation of the struggle, whose pioneers were and are to this day the Russian Bolsheviks.

It is undoubtedly of interest for every worker in the revolutionary Labour movement outside of Scandinavia to become acquainted with the Communist movement of Youth in Sweden. We shall not give a detailed historical account or description of the movement; all we intend to do is to make a few remarks on the history of the Union of Youth and a brief review of the present situation.

In the eighties of last century, Sweden, owing to certain circumstances, was ripe for the beginning of a working class movement, and Socialist propaganda, through agitators and small newspaper leaflets, penetrated into such layers of the population which the spirit of the time made singularly responsive to it. Organisations began to spring up all over the country. In the early nineties an experiment was made in Stockholm of instituting socialist Sunday Schools, and within a few years, independent organisations of young workers, men and women, sprang up in various places. These local groups formed into a union—which, however, in the first years of the Twentieth Century, lost itself in the jungles of Anarchism and never had much influence.

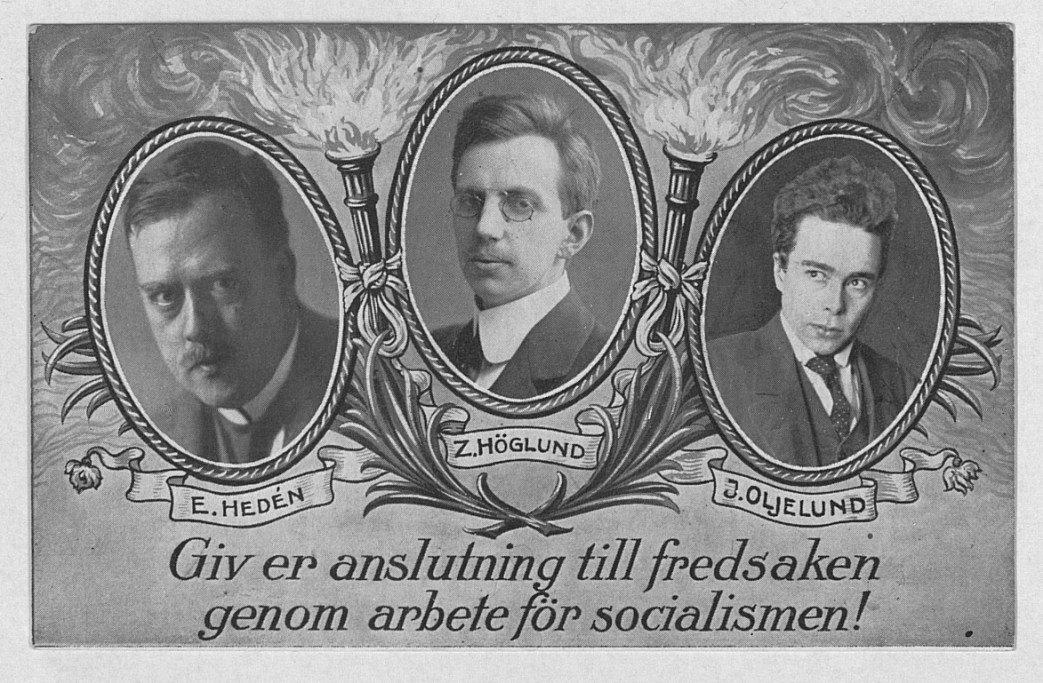

In March 1903 several of the more considerable Social organisations separated from the rest and formed a Social Democratic Union of Youth connected with the old Labour Party, which did not at the time have any influence in parliament, and was very different from what it came to be in later years. The first years of the Union’s existence were a period of intense work, directed partly to the creation of the greatest possible number of local organisations, partly to the assistance of the labour movement generally. The Union of Youth, as soon as born, at once started an organ of its own, a monthly, with the title of “Forward” (“Fram”), which quickly spread and which conducted a successful agitation in favour of young workers standing by themselves and forming independent self-reliant organisations. In the Summer of 1905, when the Swedish-Norwegian union fell apart, the two-year-old Union of Youth first began to act on a large scale. The Chauvinists shouted themselves hoarse calling for war measures against the sister country. “War with Norway!” became the watchword of the nationalist crowd. Among the working class demonstrations began, protests against making war on a sister nation, the other half of the Scandinavian peninsula—and foremost in this protest was the Swedish working Youth. In connection with their Congress of 1905, a campaign was organised against armaments and intervention. The Congress appealed to the young people and to the working class generally in a brief but glowing manifesto, calling on them to stand shoulder to shoulder for the preservation of peace; “Peace with Norway!” became their watchword—and the peace with Norway was not disturbed. But for this manifesto Z. Hoglund got six months in prison, the same Hoglund who afterwards, in 1909—1917 became the first standard bearer of the “red” movement of Youth in Sweden. The following passage from the manifesto will give an idea of its contents:

“The Youth know their duty, and will not allow themselves to be used for a war against the Norwegian workers, who understand very well that the Swedish laborers will turn their weapons—should they be forced to use them—not against the Norwegians.”

After 1905 the work of transforming the organisations of Youth into one mighty fighting body was carried on. Notwithstanding some difference of opinion on the question of independence (some would have subordinated the Union absolutely to the Party managers) relations with the Party were, on the whole, satisfactory. Up to 1908 these differences concerned only one or two questions. From that time on, however, everything changed. In that year the Social Democratic Party assumed a considerably more influential position in the Riksdag, after the Party’s success at the elections. Branting made his appearance there, at the head of the Socialist fraction, which had more than doubled in number.

About the same time the consequences of the economic crisis became apparent; after the great strike of 1909, which ended in defeat (according to Scandinavian standards it had been a grand collision between Labour and Capital) there followed a series of conflicts, in the labour market, unlucky for the stepchildren of capital, and the workers turned to political reform work in the hope of thus relieving their oppressive situation through the medium of the parliament. At the same time the Labour movement passed through another crisis; numerous workers who figures on paper as members of Trade Unions, left them, and a great many active members became victims of the great strike; for the vindictive employers composed “black lists,” owing to which the “guilty” could find work nowhere in the country; nothing remained to them but to emigrate. The Union of Youth suffered most of all. But the “Red” boys and girls were gaining strength in spite of everything, and a year after the great strike, the forces of the entire movement were completely restored, thanks to the energy of the Union of Youth.

In the meantime differences with the Party had matured in the Union; for the parliamentary fraction, headed by Branting, began more and more clearly to manifest its intention to lead Social Democracy into the opportunist camp. At the Union’s congress of 1909, its “Left” wing definitely asserted its will at the election of the Union’s Board of Managers, who, to a man, joined the ever-increasing opposition, which struggled against the Party’s deterioration.

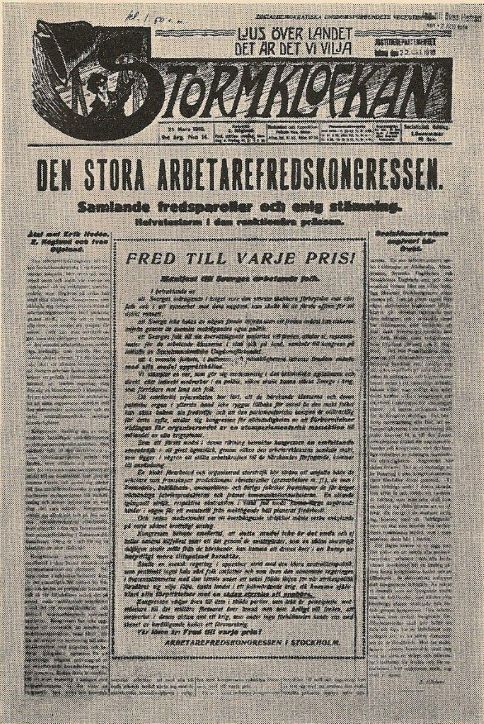

From the year 1909 there began to appear in Stockholm, at the initiative of a few clubs, a weekly paper, edited by Z. Hoglund. This paper, “The Alarm Bell” (“Stormklockan”) was by decision of the congress declared to be the Union’s official organ equally with “Forward.” After the parliamentary elections of 1911, when, for the first time, took place the Party’s so-called “break-down,” while Social Democracy gained a still more numerous representation than before, the country got a liberal government and the Party continued to rule. This was assisted by the fact that a considerable portion of the so-called bourgeois radicals, among whom was the subsequently famous Baron Palmstierna, went over to the side of Social Democracy much reinforced owing to the elections. The “right” wing of the Party began to pave the way for the admission of Socialists into the cabinet, while the Party, in its general policy, entered into intimate relations with the bourgeois “lefts,” the liberals.

In 1912 there was another Congress of the Union of Youth. This Congress declared against the entrance of Socialists into the ranks of government and against any relations with the bourgeoisie, openly emphasizing the will of the working youth, that the masses should firmly stand on the ground of the class struggle. Then all members who were loyal to the Party and true to Branting went out of the Union. On the other hand, many members of the Union expressed approval of the “Alarm Bell,” on account of that paper’s constant, sharp criticism of the opportunist leaders. From this moment—that is to say, for the last eight years–we can speak of a right and a left wing in the Party, the latter being in a great measure supported by the sympathy of the members of the Union of Youth. However open collisions between the two wings occurred only when the war began, when the Party management concluded a “civil peace” with the bourgeoisie, and began to share in the work of reorganization of the army, which resulted in a “budget of national defence” unheard-of for Sweden and her scanty population.

Immediately, after the war began, the Party held a convention, at which Branting by threats of resignation compelled a decision in favour of a liberal Socialist coalition cabinet. This was a new and supreme manifestation of the treacherous policy toward the working masses which has characterized the conduct of the Social Democracy for the last few years.

To this the Congress of the Union of Youth, which took place somewhat later, toward the end of 1914, responded, on one hand, by renewed attempts to obtain the recognition of the Union’s complete independence, and on the other, by a sharp protest against the transformation of Social Democracy into a bourgeois party and the petty barter conducted with the bourgeoisie by a majority of the Party’s parliamentary group. The attempt made in 1915 to draw Sweden into the world war on the side of Germany met with the firm resistance on the part of the peaceably-inclined working class. (The Party did not use all its power to fight the criminal game of speculating with the war, but the “Alarm Bell” took advantage of the opportunity, in the summer of 1915, to show what zealous pro-Germans were some of the more conspicuous “comrades” of the “right” wing, who openly invited recruits to the so-called “activist” clique which “agitated” in favour of Sweden’s coming out boldly for defense of the Fatherland—of the Kaiser and Krupp.

The Party youth, organised in an union of their own, took on themselves the task of proving the necessity of class struggle for Sweden as well as for other countries, and undertook the propaganda of revolutionary Socialism among the working masses in the spirit of genuine Marxism.

When, after the wreck of the Second International, the red banner was again raised all over the world, and, at the initiative of the Russian and Italian comrades, at the Zimmerwald Conference the first blow was the struck at the social-chauvinists of all countries, the Socialist Youth proved themselves ready for events: they sent two representatives to Zimmerwald, and declared their adhesion. After this conference the Union of Youth entered into close contact with the revolutionary currents which were all the time gaining strength in the belligerent countries, and became the vanguard of the Zimmerwald International in Sweden. At the same time the conflict of the young people with the Party entered an acuter stage, as the latter’s course inclined steadily to the right, sinking deeper and deeper into the slough of civil peace.

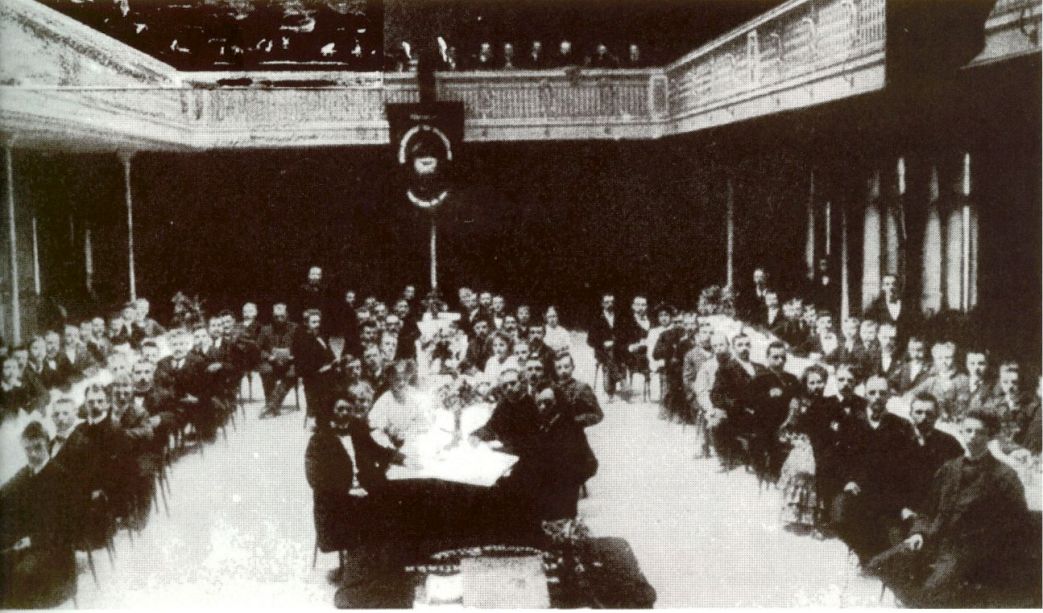

In the beginning of 1916 Sweden was again threatened with the danger of being drawn into the world war, and, it proving impossible to induce the “right” wing of the party to organise measures for averting the criminal speculation with the war, the Union of Youth determined, entirely on their own responsibility, to convoke a Labour Congress on the question of peace. It assembled in Stockholm, in March, 1916, and, besides the delegates of the Young People’s clubs, there came to it representatives of several Trade Unions and local Party organisations, wherein the majority consisted of members of Young People’s clubs and other radical elements, convinced of the necessity of an organised struggle against the German agents who were conducting the agitation in favour of war. Of the important part which this Labour Congress played in the campaign against Sweden’s participation in the universal slaughter, this is not the place to speak. Indictments were laid against thirty comrades, and three of those who attended the congress were tried for high treason. Another consequence of this Labour Congress was that the dissensions in the Party rapidly led to a rupture. The fact that the bourgeois circles of the Social Democracy joined the movement against the congress and those who had taken part in it, did not cause any particular collisions between the two currents. But dissensions took place about this time in the organisation; the group in the Riksdag fell asunder; a group of about ten members formed a “Left Socialist” independent group, separating from the rest of the faction, which consisted of about a hundred members. I have not, unfortunately the precise figures at this moment.

In May the members of the Young People’s clubs, together with the older Party comrades of the “left,” began to issue the “Politiken,” which at first came out every other day (a daily now), as the organ of the Communist movement in Sweden, under Ture Nerman’s editorship.

Thus was sharply marked the divergency of views which was to lead to a complete rupture between the two currents. In February, 1917, a Party conference was convoked; the decisions it took clearly demonstrated that the Union of Youth and the Social Democratic Party had practically nothing more in common, and that there was no hope whatever of forming a majority in the Party in favour of a revolutionary Socialist point of view. A “Left” Social Democratic Party was formed, principally through the efforts of the Union of Youth; then “Politiken” began to appear daily, and many provincial organs were founded. Half the shares of a publication by the Union of Youth, called “Forward,” in memory of the Union’s first organ, suppressed in 1912, were taken by the Party. After the new constituent convention in May 1917 and a congress of the Union of Youth had taken place simultaneously, these two organisations, which covered the whole country, took up the joint work of preparing the ground in Sweden for the liberation of the workers, making it their first task to unmask to the workers the treasonable intrigues of the social patriots and the capitalist oppressors.

During the last three years the Union of Youth no longer has had to devote most of its time to an internal opposition Party policy, and the struggle for achieving a majority in Party organisations. It could give its best to its real object: the education of the young people. The number and importance of Unions of Youth have greatly increased of late. But, at the same time, they neglect no chance of helping the Left in its during revolutionary actions. They put their greatest, most active strength into the struggle against the base campaign which the bourgeoisie and Branting’s followers conduct against Soviet Russia, who is defending her existence with such fearlessness and firmness.

As mentioned above the Union of Youth resolved to join the Third International (when the question of adhesion to the Third International was put to the vote, there were only a few “noes”); that the Social Democratic Union of Youth is carrying on a political struggle against the bourgeois democracy and recognises the dictatorship of the proletariat as a form of transition to the new social order. The constitution of the Union of Youth defines its aims as the propagation of Communist ideas, more particularly among young people. The programme of the Union emphasizes the necessity of disarming the bourgeoisie; this clearly shows the Union’s point of view with regard to militarism, in contrast to all the obscurities of the old programmes in the matter of disarmament.

The Social Democratic Union of Youth (the old name is retained, though with the addition “of the Third International,” is at the present time a powerful and active organisation. To give some idea of its activities, I will say something of what it has accomplished in 1919.

In this year as in former ones, Union agitators travelled all over the country, acting on a definite plan. Their work consists principally in giving evening lectures, partly in localities where there are local organisations of the Union, partly where there have been as yet no such organisations. In addition to this a new method of agitation was tried during this year: organisers were sent out, who were to stay each one month in a given locality, spending several days in this or that place, giving public lectures, instructing clubs, organising the propagation of literature, doing all sorts of enlightening work, in short assisting the organisation of the Young People’s Communist movement. Five organisers worked 126 days in all, during which time they gave 97 lectures, delivered 42 addresses of instruction. It has now been decided to appoint several permanent organisers in districts which are most in need of organising experts. In the course of last year a beginning was also made with a systematically organised body of cyclist agitators. In those parts of the country where railway communication is poor, these special agitators sent by the Union of Youth travel on bicycles. There are 46 of them, and their special work consists in propagating literature and exerting personal influence on the rural population. In the course of this one summer they organised 791 open meetings and 46 closed discussions, at which the members of Young People’s clubs were given instructions about organising new clubs. For travelling about the country the Union’s agitators also utilized “Red” automobiles, each holding two orators and a lot of revolutionary literature; the Union shared the use of these motors with the Left Party.

It should be remarked here that the Union of Youth generally used several kinds of agitation entirely new to Sweden. As to the Red motors, when, in 1911, the “red” Youth of the country first began their automobile excursions, they excited extraordinary interest and universal attention. It was then a great novelty to the bourgeois organisations; they began later with their “automobile agitation,” but never had such brilliant success with it as the Union of Youth with their red motor. The political caricature also was as yet a thing unknown in Sweden. It was the “Alarm Bell” which first made use of it, with the assistance of two talented artists. These are a few instances of the wealth of ideas, of initiative, the perfection of organisation which distinguish this “criminal youth,” as one of the organs that crawled before the bourgeoisie had the impudence to call them.

Among the things accomplished in the course of the year 1919, should be noted the organization of three special “agitation days”; “Red Sunday,” the 2nd of March, devoted to spoken and printed agitation for Soviet Russia; “The Day of the International of Youth,” the 7th of September, and lastly, the “Day of the Second Anniversary of the Russian Proletarian Revolution,” the 7th of November. On these days special orators went to various places and everywhere distributed literature specially prepared for the occasion. A file of the “Alarm Bell” was published in a special edition of 1,500,000 copies; besides which was published a pamphlet against bourgeois charities; also, jointly with the party, the Union issued special First-of-May and Christmas numbers. And, over and above all these things accomplished by the Central Committee of the Union of Youth, the work of the regional organizations should be mentioned. For the Swedish Young People’s Union is divided into 25 regions, each having its own committee, entrusted with the supervision of the work of the local organizations (clubs), within the region.

In the course of the past year the Union of Youth extended its activities so as to enclose the children. In spite of the bitter and obscurantist resistance offered by capitalist society in both church and school, the members of the Union of Youth in about 50 localities rushed into the thick of the fray, with the war-cry “See to the, children”; in order to collect and organize groups of youngsters from 8 to 15 years of age. A special children’s monthly was published, and special instructors were appointed—one in the Union’s board of managers and one in each of the district committees and club committees.

The Educational work deserves a separate chapter.

The Young People’s Union made every effort to foster among the workers the wish for knowledge generally and for Socialist learning in particular. There is in Sweden a general workers union for the propagation of knowledge, common to both the “left” and the “right” Socialist Parties, as well as to the Trade Unions, the Syndicalist and New-Socialistic (Anarchist) groups. The educational work is conducted “circles” belonging to focal organisations—and our Union of Youth possesses an absolute as well as relative majority in the general number of “circles.” In addition to this the Union carries on Communist work, the programme of which includes, among other things, reading and discussing the works of Engels, Bukharin, Radek, Marx, Lenin and others.

We cannot here dwell with greater detail on this side of the work, but must be content with a general deduction. The instruction of the members, especially the Communist branch, has developed considerably during the past winter. The number of single lectures as well as of sets of lectures, has increased amazingly in comparison with the preceding year.

Lastly the propaganda has been going on among the soldiers, who were always year dear to our hearts. Our efforts at revolutionizing the Trade Unions have not been fruitless either. This is proved by the fact that many Trade Unions have refused to join the “right” Socialist Party. All this, together with the above-mentioned facts, gives a tolerable idea of the activity of the “red” youth in Sweden during the year 1919.

The Union of Youth already numbers about 500 clubs, with a membership of over 25,000 (For comparison’s sake we may remark that the “Left” Party numbers not much over 20,000 members, although many members of the Youth belong also to that). We observe of late that, in the various countries to which the activity of the International of Youth extends, the Unions of Youth multiply as rapidly as in Sweden, but, in view of the size of the latter’s population it may be said that, not a single country compares with Sweden, either as to the number of members or as to the extent of the organizations’ activities. For Sweden has, at the present time, a population of only 5 to 6 millions, and it will need no little exertion on the part of any Union of Youth in one of the larger states to bring up to a similar level the relation of membership in proportion to population.

The Swedish section of the International of Youth makes every effort to assist the unification of forces, with the object of demolishing the Chinese wall which Capitalism has erected between the several countries. The Swedish Union of Youth, jointly with Swiss and Italian comrades, took part in the Congress convoked at Berne in 1915. They had representatives at the Berlin congress in 1919; now they have begun to issue a periodical, “The International of Youth,” in Swedish, and all possible measures are being taken for the propagation in Sweden (and even in Western Europe and America), of information concerning the activities of the International of Youth and its aims.

As in all the countries where capitalism still lords it over the labouring class, exploiting and oppressing it, so in Sweden the condition of the proletarian youth is hardly one to be envied. From early childhood the boys and girls of city and country have to leave home and go off to hard work in the mines, in factories and mills, or in sewing workshops,—on sea or land or in forests; after a brief and unsatisfactory course at primary school, they become, equally with their parents, brothers and sisters, the objects of capitalistic exploitation. But work comes harder to the young than to the old generation; they are not yet reconciled to their bondage, have not quite yielded yet to the influence of the clergy and the bourgeois press and many other means of acting on men, familiar to bourgeoisie.

Nor do the young easily give in to the witchery of the social patriotic demagogues and bourgeois democracy. It is significant that in Sweden, where a man like Branting just now “reigns” supreme, where for more than two years the Liberal Socialists have been at the helm, and where now these several months, the country has been ruled even by a socialtraitorous government, with whom the capitalists naturally are delighted,—that in Sweden, where the labourers have not yet seen through the amazing comedy which is being acted by the government Socialists, it should be just the young people who are the most dangerous foes of this gentry and their flunkies. The red youth of Sweden will never forget that, when these last years, the stormy waves of the World Revolution rolled up to the comfortable shelter of the old Social Democratic Party, and when all the elements for immediate action were right there ready to their hands, this worthless, thoroughly rotten Party betrayed the people’s cause. The old workers forget more easily. Already they have forgotten the famine caused by the Entente blockade at the time of the war; they do not remember how Branting and his fellows when striving for power, promised universal suffrage, important Socialist reforms, even socialization on a large scale—and how he afterwards deceived all expectations. Young People’s memory is fresher; they do not forget the appointments, they do not forget for one thing, that the suffrage “reform”— deprived them actually disenfranchised them. Yet, although it is easy to get the proletarian youth to work, for the new ideas, still it proves more difficult to induce them to work on a wide scale within the Communist organizations; in the interest of the cause preference should be given to a separate independent young proletarians’ movement with regard to the party for that indicates a stupendous increase of revolutionary creative energy.

We need to institute “children’s gardens,” (Kindergardens); Communist work among children, as we showed by Sweden’s example is something entirely different. The school for boys and girls, acting under the supervision of good-natured uncles and aunties has no meaning in the period of the “new-evangel,” what we want now is advance detachments of young people for class strife and war united into organizations of their own, acting each for itself, but in complete harmony with its class comrades, soldiers of the international Communist army. Most likely this way of looking at things will not be intelligible to all. Nevertheless there is no doubt that the very best way of training the proletarian masses for participation in the revolutionary struggle consists in forming of them special fighting battalions for that purpose. The Young People’s movement in Sweden is the best proof of this. The movement will in this respect gain immeasurably in importance if, by proving its viability it helps to prepare the soil for the International of Youth in countries in numbers under the red banner of the freedom which, so far, it has been little influence or is yet quite unknown. The older comrades in the Third International should lend a helping hand to the Communist International of Youth, the members of which come forth in ever greater numbers to the red banner of freedom.

Moskow, June 1920

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n11-n12-1920-CI-grn-goog-r3.pdf