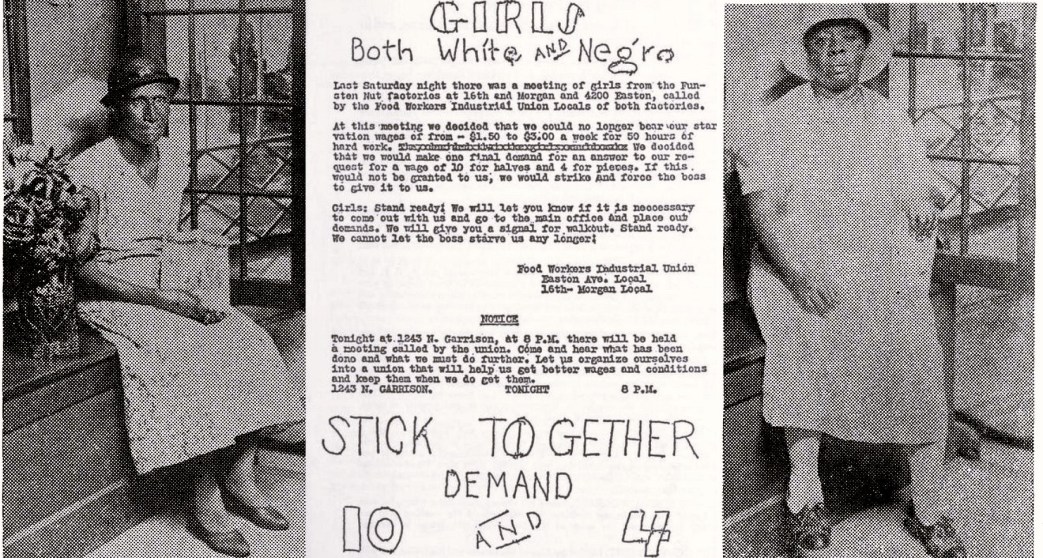

Two of its leaders tell the story of 1933’s historic Funsten Nut strike. The T.U.U.L.’s Food Workers’ Industrial Union organized a successful strike in the St. Louis nut picking industry with its almost all Black women workforce.

‘We Strike and Win’ by Carrie Smith and Cora Lewis from Working Woman. Vol. 4 No. 6. August, 1933.

The working women should follow the example of these militant and courageous working-class leaders, and have faith in their own abilities to struggle, fight and organize. What has been done by the comrades in St. Louis can and should be followed in every section of the country in struggle against the slavery imposed upon the women through the National Industrial Recovery Act.

By CARRIE SMITH

I worked for the same company, am 42 years old, married. I have the Funsten Nut Co. of St. Louis for the last 18 years. I have worked in every one of their shops, in the last shop I worked for the last three months. I belong to a fraternal organization, and to a church. Before the strike I was earning $3.00 per week, after the strike and at present I am earning $9.00 per week.

I didn’t know about the movement or the union until a week or ten days before the strike. Laura, a girl in the Easton shop, told me about the union, and how we can overcome our miserable conditions in the shop. I had worked in the Easton shop and quit because the boss used to curse at us so much. When I heard about this movement, I was in a hurry to get in. The next meeting was on a Wednesday night, but I joined on Sunday night, and the strike was pulled in a week later.

To be Thrown Out of Jobs.

I heard that the Easton shop was to close down and move into Kinlock County, thus throwing the girls out of work. I let the girls in that shop know about it. Comrade Shaw, the organizer of the Communist Party in St. Louis, asked me when the best time to pull the strike, and I said Monday morning, because the shop was to close down the following Thursday.

The Strike Spreads.

Monday morning when I came to work, I told the girls, “In here with your heavy stuff!” They wanted to know what I meant, and I told them that the girls in the Easton shop were striking at 7:30 that morning and would be here at 8:00 a.m.

They were to signal me, with a whistle, but I never heard it, but looked up and saw a truckload of girls and told those in my shop, “The heavy stuff’s here!” Get your hats and coats and let’s go.”

The foreman went to lock the door, I said, “Don’t lock it a second time!” He said he wasn’t going to lock it, I said, “Darn it, get away from that door.” Then I called to the girls to come, girls from both sides marched.

Negro and White Join Strike.

The white girls stayed inside. The floorlady told them that all the colored girls were going on a picnic, one white girl looked out, and she knew what kind of a picnic it was.

The floorlady told her that if she looked again, she wouldn’t have a seat. She saw enough to know that we were not on a picnic. Tuesday morning all the white girls went on the picket line, joined hands with the colored girls and went side by side.

When we walked out, we marched to the 15th St. park, there they made me chairman of the strikers, ten workers were elected as a committee and we went to the main boss. He said he would see only two girls. We sat in conference with him for two hours. He said he couldn’t raise wages. We left, and went back to wages. We left, and went back to the headquarters, there we consulted our organizer, and the next morning we decided to call Mayor Dickman.

Rabbi Isman had the committee to Wednesday of the next week, meet with him and his council. After talking he said he would take it up with Mayor Dickman, but that was the end of the story. On Monday we had a demonstration at the City Hall. I was the first speaker and Mayor Dickman was the second. The committee went upstairs with him and we made arrangements to meet with him the next morning at 9:00 a.m.

We went the next day and the Mayor asked me, “Why didn’t you get in touch with the Urban League to represent you instead of the Communists?” I told him, “The Urban League and all the rest of them knew we were sitting in that sweat shop for nothing. None came to our rescue but the Communist Party and I think that I have just as much right to choose who I want in my council as you have in yours. As for the Communist Party, I was with them.”

He told me, “Leave the City Hall at once.” But I just sat there, and he got so mad he left himself. We were excused for lunch and told to come back at 3:00 o’clock. When we came back the Mayor was smiling at me. He said, “Mr. Funston wouldn’t pay $1.00 per box.

Mayor Sides With Boss.

I told him that we were working people and couldn’t have a decent living out of our work, why couldn’t we, we obeyed the laws of the city and loyal citizens. Why can’t we get a living wage? He said, “Mr. Funston wasn’t making much and could not pay the dollar.” We said, “If he won’t pay the dollar, we won’t take under 90 cents per box.” They let us go and called Funston back. Funston agreed to pay 90 cents then.

However, I must say that the Funston Nut Shops are closed and that no one else except members of the union can work in this shop. On thousand eight hundred ninety two girls joined the union and 52 girls joined the Communist Party. Over 50 the Young Communist League. The girls are loyal to the union. “You better not say anything against the union or they will fight you.”

By CORA LEWIS

I am 43 years old and a widow with six children, the youngest being eleven years old.

I belonged to the Good Samaritan Lodge, and belong to a church.

Before the strike I was earning $3.00 per week, today I am earning $6.30 per week.

I work in the Easton Shop. One of the girls working in the shop was asked by her brother who is a Communist about conditions in the shop, and he got her to get a group of girls together to take up the grievances in the shop.

I heard about it and fell head foremost into the work. At first we met at homes. At the first meeting there were only three girls. At the second there were five, at the third there were six, at the fourth there were twelve, and that the fifth meeting we began to discuss the demands.

At this shop I was made chairman. In the discussion someone proposed higher wages. The first demand was ten and four (10c for picked half shells and 4c a lb. for broken pieces).

We Organize a Union.

At this meeting the eight girls were already organized into the union, and they succeeded in beginning the strike. At the next meeting we had about 92 girls, a committee of ten girls went to see the foreman with the following demands, 10 cents for picked half shells and 4 cents a lb. for broken pieces; definite answer within ten days, and that if we wouldn’t get an answer to our satisfaction, then we would walk out.

At the end of ten days we went to the foreman again. He wouldn’t say, he didn’t know, and if we didn’t like it to get in the street and find a job.

Win Weak Sisters For the Strike.

One girl who walked out of the Easton went back, served dinner and returned to work. Her sister came and told the Party what she did.

Carrie Smith and I went to her home. Carrie won her to the strike again.

Next morning the picket line began. Four girls picketed, two white and two colored, and the International Labor Defense worked with us side by side and helped to get us out when we were arrested. The foreman promised us that if we didn’t walk out that he would call the boss and see what he could do, but instead he called the police.

Communist Party on the Job.

The Communist Party had trucks there, and the police told them to move on, one girl got scared and jumped off the truck.

The girls did not want to picket the back entrance because they could not see what was going on, but we must that brothers, say sisters, daughters, mothers, children and all went the picket line. One said, “that his wife was earning the living and that she went strike in order to get higher wages, and that if anyone lays a hand on her, they would never live to see the day thru.”

The children took it for granted, that they should the picket go on line.

My daughter pickets all the shops in the city. The strikers met every day and every night. Committees from all the shops met at the headquarters.

At the beginning all but 22 girls joined the union, but now all the girls are in 100 per cent. Our demands to the boss were the following:

1. Ten and four.

2. All strikers to go back to work before anyone else.

3. Equal pay for Negro workers for equal work.

4. No cheating on scales.

5. Removal of general inspector.

6. Recognition of shop committees of union.

We Won All Demands.

We won all these demands, the grievances in our shop are all done away with, and all are settled with the shop committee of four and the union.

I was elected to be chairman of the shop committee. The girls are all tickled to death with the union. We have no more terror from the foreman, he quit, and a new one was hired. The girls are loyal to the union, and meet regularly with us. When we went to the Mayor in discussion, I told him that my youngest boy was in the reform school. He wanted to know why and I told him, “Working for Funstan, five days and one half and one hour over the half day in a week with such low wages, I was unable to support the boy, he tried to support himself, in doing with whatsoever was in carried sight, police arrested him, took him to the House of Detention, gave him a trial and sentenced him indefinitely to Bell Fountain Reform School. That was in the last council.

The Mayor Can’t Fool Us.

“Mrs. Lewis,” he said, “you certainly fought a hard fight. You have gained a victory without a blemish, so I am bound to give it to you.”

But I must say that it was not he who helped us, but because all of the girls white and colored stuck together and determined to win this strike, that is why the victory was gained.

The Working Woman, ‘A Paper for Working Women, Farm Women, and Working-Class Housewives,’ was first published monthly by the Communist Party USA Central Committee Women’s Department from 1929 to 1935, continuing until 1937. It was the first official English-language paper of a Socialist or Communist Party specifically for women (there had been many independent such papers). At first a newspaper and very much an exponent of ‘Third Period’ politics, it played particular attention to Black women, long invisible in the left press. In addition, the magazine covered home-life, women’s health and women’s history, trade union and unemployment struggles, Party activities, as well poems and short stories. The newspaper became a magazine in 1933, and in late 1935 it was folded into The Woman Today which sought to compete with bourgeois women’s magazines in the Popular Front era. The Woman today published until 1937. During its run editors included Isobel Walker Soule, Elinor Curtis, and Margaret Cowl among others.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/wt/Working-Woman-v4n6-OCR-aug-1933.pdf