The second chapter of Mary Marcy’s first book, ‘Out of the Dump: A Story of Organized Charity,’ illustrated by Ralph Chaplin and originally serialized in the International Socialist Review. Telling of an orphaned girl of the working class having to navigate Chicago’s charity system to survive, the story is close to Mary’s own. While still a teen she lost both of her parents becoming the primary care-giver for her two younger siblings, Hazel and Roscoe, as they were shuttled between family and ended up in Chicago with Mary working as a telephone operator. Later in life, after being fired as a whistle blower from the pork-packing industry, she worked for Kansas City charities, which she would be severely critical of and also certainly informed this story.

‘With the Upper Element, Chapter II’ by Mary E. Marcy from Out of the Dump. Charles H. Kerr Co-Operative, Chicago, 1908.

I WAS ELEVEN when I went to live with the Van Kleeks nine years ago, and for several months I felt that I was in a fairy land. Growing flowers I had never seen before and only to look at them filled me with joy. At first the army of servants awed me, and I was never weary of watching the splendid horses, the luxurious carriages and the wonderful automobiles.

I had never imagined dresses of such exquisite texture, nor china so rare, nor real gold plate anywhere outside of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. In the great house, surrounded by the grounds filled with stately trees, I was happy for a time to be an unmarked* observer of the life of the Leisure Class. Mrs. Van Kleeck was usually so overwhelmed with receptions, musicals, balls or dinners that she forgot all about me until she was called upon for her quarterly report from the Home Finding Department of the Charity Organization Society.

In all my life I had never known people who could afford to satisfy their desires, and the Van Kleecks had only to want and be filled. It was to me a new order of things to hear little Holly Van Kleeck, aged six, demand a new pony and English cart, ANOTHER miniature automobile or a small duplicate of his father’s Swiss watch set with diamonds, or some other inconceivable extravagance, and everybody running around to satisfy his demands. I pinched myself when I saw him bang the same watch over his tutors head and break it. The whole world seemed turned upside down.

But money was nothing at all to the Van Kleecks. Holly had a dog harness for his bull terrier, pegged with knobs of beaten brass, that cost more than a year’s rent down at the Dump. And his father roared with’ laughter when Holly threw it into the blazing fire during an evening romp.

It struck me with continual wonder, that first year, to see lap robes, the price of which would have fed the Higgenses royally for a whole year. I was dumb before a homely red vase that was worth money enough to have saved Pete Miller’s leg when it was crushed, by the street car, and amputated a few days later on account of unskillful treatment. It was unbelievable that any woman should spend enough money on a single gown, to have bought a house and lot in the Alley.

The maid in the left wing enjoyed telling me about these things for I sat mouth agape drinking in the new wonders like a young gourmand, or sat stunned trying to understand that there really was as much money in the world as the Van Kleecks seemed to possess. I had always had grave doubts upon the matter before. Indeed, I was too amazed trying to assimilate these new standards to feel much loneliness. It was a glorious and continuous fairyland performance and I only awoke after six or seven months of it.

At the death of his father, Hollister J. Van Kleeck, Jr., had been left a controlling interest in one of the largest wholesale and retail dry goods houses in America. He was just thirty-one. Prior to that time he had spent his days generally like most young Americans who have more money at their disposal than they know what to do with.

When Hollister J., Jr., became head of the firm he knew less about that business and business in general than the greenest office boy in his own employ. But that did not matter, because his father had tied up the estate so that all Van Kleeck, Jr., could do one way or the other was to DRAW DIVIDENDS. And his son was quite content. After all, I guess dividends are the object of business enterprises, so the old man attained his end.

And old Van Kleeck had left capable men at the helm of affairs who were constantly employed in finding avenues of greater profit into which to steer the business barque. So there was no good reason why his son should roll up his sleeves. And he didn’t. He just kept on in his old ways, with the slight diversion of marrying the richest girl in Pittsburg. It was generally more than likely that his wife herself did not know where he was when he went out on a fishing trip or overland with an automobile party. But it did not hurt the business a bit.

But during my time at Guildhall, Mr. Van had become better known in his home town. He even pretended to talk business occasionally. I know sometimes I heard him talking about the “business interests,” and he was made President of the Commercial Club. What the papers said about him is something we should all bear in mind. Their eulogies are surely—fitting.

They said he had become a power in the community and in the whole United States through his wonderful business foresight, his financial acumen, and his integrity. I suppose if we are going to point the moral, we will say, “Choose a RICH FATHER.”

Mrs. Van Kleeck’s father controlled the P.D. & Q.R.R. and two or three other Western roads besides, and riding in a private car was more common to her than a street car ride is to the children in the Dump. There were only two children and President White gave each of them a block of P.D. & Q. when they married, which meant that an army of working folks would labor for them as long as they lived, and that the children of these working folks will in turn have to work for his grandchildren, if something startling does not happen before their time.

Mrs. Van Kleeck’s life before her marriage had not been much different from her husband’s. She went to college and traveled and was introduced. All her life people had been busy performing service for her, making gowns, or hats, preparing dinners, sweating, starving and dying for her.

There were the men who built the cars and laid the road and those who ran the trains and earned the money for the road. They were paid out of the road’s earnings to live on, and all the rest went to Mrs. Van Kleeck, her brother, and her father.

My brother Bob says the new capitalist system has the old monarchical and slave systems beaten to a pulp. The capitalists own the factories, the railroads or the mines. In other words, they own the JOBS. But there are not enough jobs to go around, and as a working man must have work in order to earn money to LIVE, there are always men and women who are compelled to sell themselves for a bare living. These men and women are awarded the jobs because the capitalist is in business only for the sake of PROFITS.

Whenever the workers get an advance in wages it leaves less for the capitalists; and every time the capitalists are able to force a reduction in wages, it means more for them. It looks to me as though it will be a hard matter to reconcile the boss and the workingman under these circumstances. They are bound to fight each other as long as there is any prospect of gaining anything by a struggle.

But as I started to say, Bob says the slave owner had very often to force his servants to work, but in these days the worker’s stomach pushes him on to compete and even beg for a chance to toil. The capitalist does not need to worry about slaves in these times. There are so many more men than there are jobs that there is always an over-supply of those who must work for just enough to exist on, and no matter how many of them may be killed in accidents, or through the use of cheap or defective machines, there are always a score of others to take their places.

Besides, Bob says the working people THINK they are free, so the capitalists do not have to follow the example of the Kings and oppose “Liberty. They simply scream “Freedom” from the housetops on all possible occasions and the armies of slaves go back to work with their heads filled with sawdust.

Bob says if he were a king he would go into business, abdicate the throne, lay down his scepter and talk Liberty to his subjects. Then he would give them jobs in the factory and when they made ten dollars’ worth of cloth, he would pay them $2.00 (or just enough to live on in that king’s country) and the “Glorious, Free Afghanistan Citizen” would put the new boss upon a pedestal and paint a mental halo around his head.

As Bob says, “the owner of a factory could sure put their majesties on to easier and far better paying jobs.” He thinks kinging is “crude and antiquated at this stage of the game.”

Take Mrs. Van Kleeck for an example. I guess this is the first time anybody ever hinted that she was not a public benefactor. Kings are generally considered tyrants, but Van Kleecks are regarded as the cream of the earth, and Bob says men who would balk at an emperor do a lot of side-stepping for the sake of “standing in” with the boss.

But speaking of Mrs. Van Kleeck—she scarcely knew how to dress her own hair. Many times I have heard her boasting to her maid, Antoinette, of the things she couldn’t do. In fact, I believe there is nothing useful in the world she knew anything about, and as for running a railroad—she does not even know what dividends “her” road pays. She has so much money that she does not know how much she is worth. She can speak French, of course, and German, a little, and Spanish and Italian, I believe, but she has nothing clever to say in any one of them.

When I went to work at the office of the Charity Organization Society, the first thing I noticed was a great sign placed over the door through which the “applicants” are obliged to pass when they want to ask for help. It reads this way: “ALL THINGS COME TO THOSE WHO WORK.” I thought of Mrs. Van Kleeck and I laughed inwardly for many days whenever I saw that sign.

Mr. ad Mrs. Van Kleeck and the friends in their set were liberal givers to all the charity organizations, and scarcely a day passed that an employee from the Van Kleeck stores or factory did not apply to one of the organizations for help of some kind. Five dollars a week was the average wage paid to clerks, and you can’t make that amount stretch over seven days, try as you may. Besides, the girls are required to dress well and the shabby girl will not be kept long. When a girl is trying to support her mother, or her brother and sisters on five or six dollars a week, she is pretty certain to need aid from somebody very soon. So the Emporium came to be known as The School for Scandal and many of the girls were forced to add to this pittance in another way.

It was unbearably humiliating applying at the charity societies and if you needed a new and decent waist to wear at the new job at Van Kleeck’s in the morning it would be a be dead of starvation before the “Scientific” Investigators got pretty safe bet to lay on the fact that the whole family would down to a working basis. Or they might present you with an antediluvian waist that The School for Scandal wouldn’t employ at the wrapping counter.

They will tell you, at the charity organizations, that Hollister Van Kleeck, Jr., gave a thousand dollars one year to The Home for Delinquent Females and that Mrs. Van Kleeck became so much interested in the work of checking the social evil that she put up enough money to publish a book on the subject written by one of the “Charity experts.”

There was not, however, any mention made in this book of The School for Scandal; nor was there in it anywhere a hint of a real cure for the disease.

The Right Reverend Doctor Squab tells us that religion will remove the cause; that when the heart is “purified” women will no longer “desire to sell themselves!” As though any man or any woman ever wished to sell themselves—in any way!

The purpose of Scientific Charity is to provide the members of a family with work paying enough to enable them to live, and if a hundred thousand men or women in any of our large cities should stop work to-morrow, there would be more men and women than would be needed applying to fill those positions the next day. When there are two girls for every job, you can’t get jobs for all of us. So it is impossible for the most “scientific” Charity organizations to be “scientific” much of the time.

When a “Scientific” Investigator had Kate Miller’s case in hand, Katy was working at the ribbon counter in the Van Kleeck downtown retail store. She was trying to support her mother and herself on five dollars a week, when one of the buyers took a fancy to her. He paid the room rent and bought her a new dress before he went to New York. Things got worse for Katy after that, instead of better, till the “Scientific” Investigator got hold of her. She lectured Kate and advised her to get a room with some family that would permit her to work at night for her board. Then she brought some sewing for Mrs. Miller, which she was unable to do, with her hands all pinched up from rheumatism. Katy would not go out to work evenings, because she knew somebody had to be home to look after her mother, but they moved into a cheaper room, which the Investigator found and which was so far away from the store that Katy had to pay car fare to the store or walk four miles night and morning.

Then the Investigator fussed with Katy for a while and wanted her to put her mother in The Old Folks’ Home, where Katy could support her comfortably by paying only a dollar a week. Katy finally consented, but the Investigator found that Mrs. Miller was six months below the required sixty-five years of age, or not an American-born, or that she was a Catholic, or there was no vacancy or some other unconquerable obstacle—it may have been she had not been a resident of the state over ten years—I can’t remember what it was; anyway they found Katy would have to go on supporting her mother the same as ever.

About that time the Investigator got busy on another case, but she did not neglect the Miller family. She sent down a bag of beans and some salt pork, and called around to see how they were doing about two weeks later.

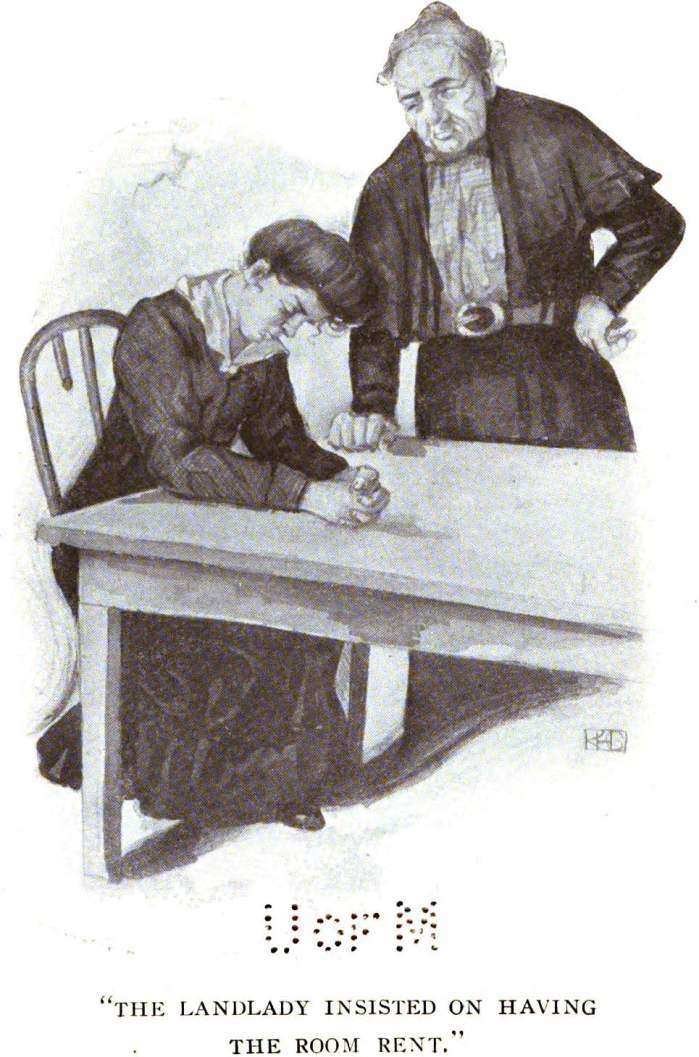

In the meantime the new landlady insisted on having the room rent when it came due. Katy kept right on in the new way till Mrs. Deneen gave them notice and then she made up her mind there was nothing in reforming.

The Investigator was disgusted when the neighbors told her about the Millers and the Society gave Katy up as a bad lot and marked “Very immoral; don’t seem to want to do right; UNDESERVING” after her name on the books. It would have done Katy no good to apply there for help after that.

What the Van Kleecks and their friends gave to the charity societies was not a drop in the bucket to what their own employes were actually in need of, but it enabled the management to turn the applicant over to the organizations. Besides, giving to charity is the best possible sort of an advertisement.

Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement. It remains a left wing publisher today.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/InternationalSocialistReview1900Vol08/ISR-volume08_text.pdf