A ‘pan-Americanist’ anti-imperialist, Fraina was deeply interested in the Americas and the role of the U.S. Much of his writings in the period immediately before U.S. entry into World War One are on the subject. Less than five years after this article, Fraina would be sent as the Comintern’s representative to Mexico.

‘Pan-Americanism and the Monroe Doctrine’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 4 No. 2. January 15, 1916.

AT the sessions of the Pan-American Scientific Congress, many beautiful things were said about the “unity of the Americas” and the great ideal of Pan-Americanism. The sentiments were sublime, the aspirations inspiring, the tangible political achievements nil. Secretary of State Lansing’s romanticism bubbled over, giving a touching color to the proceedings: “The American family of nations might well take for its motto that of Dumas’ famous musketeers, ‘One for all, all for one.’” President Wilson indulged in his usual captivating sentiments, compounded in about equal measure of evasions and generalities.

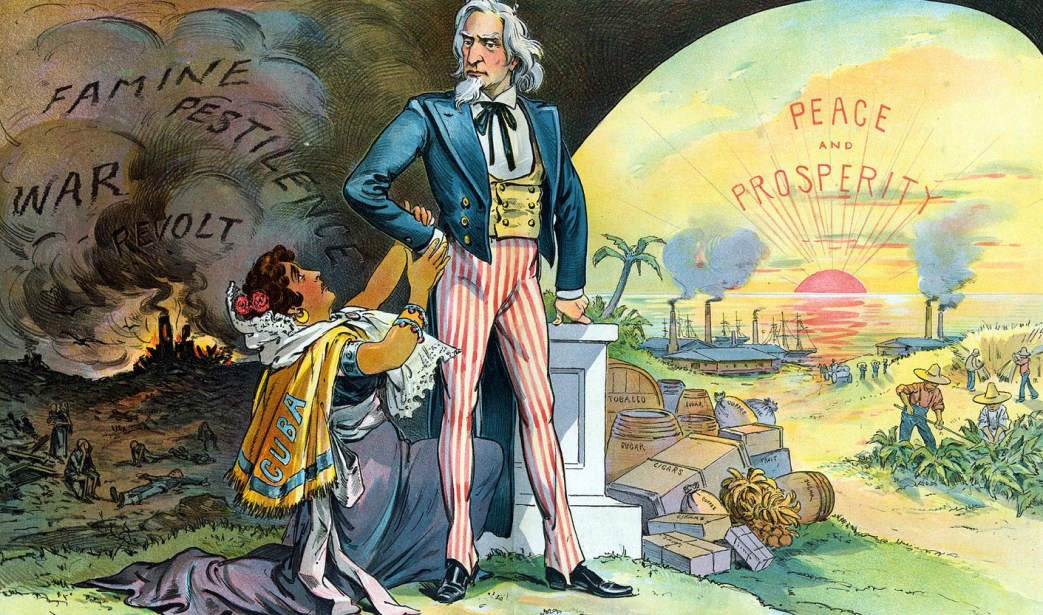

But there was no approach to a definite, sincere attempt at Pan-Americanism—the unity of the Americas. An indispensable preliminary to this unity is the recognition of the equality of all the American nations—the rejection of the hegemony of any particular nation in the American continents. But the Monroe Doctrine implies just such a claim to hegemony by the United States. The Monroe Doctrine is a national policy of the United States; it demonstrates that the United States conceives its political interests as dominant in the American continents, and seeing that within recent years the Monroe Doctrine has assumed a distinctly economic aspect, its economic interests as well. Under the circumstances, real Pan-Americanism implies the end of the Monroe Doctrine, at least as a national policy of the United States.

But in the midst of the ambiguity which was the essential characteristic of the speeches of President Wilson and Secretary of State Lansing, one thing stood out clearly and concretely: the United States, represented by the present administration, has absolutely no intention of abandoning the Monroe Doctrine as an exclusively national policy. Wilson made this clear:

“The Monroe Doctrine was proclaimed by the United States on her own authority. It has always been maintained and always will be maintained upon her own responsibility.”

Pan-Americanism was interpreted by Lansing in terms as futile as they are ambiguous:

“When we attempt to analyze Pan-Americanism we find that the essential qualities are those of the family—sympathy, helpfulness and a sincere desire to see another grow in prosperity, absence of covetousness of another’s possessions, absence of jealousy of another’s prominence, and, above all, absence of that spirit of intrigue which menaces the domestic peace of a neighbor. Such are the qualities of the family tie among individuals, and such should be, and I believe are, the qualities which compose the tie which unites the American family of nations.”

This Pan-Americanism—naturally! since it is meaningless—is, said Lansing, “in entire harmony with the Monroe Doctrine.” And Lansing emphasized the fact that the Monroe Doctrine “remains unaltered as a national policy of the United States.”

Ambassador Suarez-Mujica, of Chili, who presided at the opening session of the congress, expressed the belief that the Monroe Doctrine was about to be absorbed in the larger doctrine of Pan-Americanism. This belief, this hope, was utterly shattered by the declarations of our Chief Executive and his Secretary of State. The United States refuses to recognize the other American republics as sovereign states on an equal footing with itself.

In his speech, President Wilson dealt with his proposed plan for closer union among the American republics. Closely examined, the proposed plan shows slight if any resemblance to genuine Pan-Americanism; in fact, in the phrase of one of the Latin-American diplomats, it merely “legalizes ideas and practices” that have grown up in the relations between the American states. Its chief purpose is to secure economic and governmental stability in the Latin-American republics. Speaking about the proposed plan, Wilson emphasized particularly the necessity of preserving domestic as well as international peace, and made his meaning clear in no uncertain terms: “Revolution tears up the very roots of everything that makes life go steadily forward and the light grow from generation to generation.” Accordingly, the proposed plan is nothing more than an attempt to insure conditions of “law and order” in the republics of the South. ‘Law and order” and “stability” are prime pre-requisites for the protection of American investments.

There is, no doubt, a necessity for genuine Pan-Americanism as a first step to world federation. But, as we have pointed out, this pre-supposes the abandonment of the Monroe Doctrine as a national policy of the United States. Is there any such tendency? On the contrary, the Monroe Doctrine is becoming more and more the conscious instrument of American Imperialism. Before the war, there was a certain sentiment among our publicists in favor of merging the Monroe Doctrine into the larger doctrine of Pan-Americanism. But now that American Imperialism is asserting and clarifying itself, becoming aware of the issues at stake and determining to seize world power, if it can, the Monroe Doctrine is being strengthened, amplified, rough-hewn into an instrument of aggression. The Monroe Doctrine is no longer the doctrine of Monroe, but a doctrine given its definite Imperialistic tendency by President Roosevelt, the end of which is domination of the American continents. Pan-Americanism, in a measure, is the off-shoot of the Monroe Doctrine, the one essentially economic, the other essentially political.

Genuine Pan-Americanism might be based upon the recognition of the equality of all the American states, and the organization of a customs-union—zollverein—that should eventually include Canada. But the United States, with its Imperialistic Monroe Doctrine, offers a political obstacle to this plan; while the Latin-American republics offer an economic obstacle, in that their economic interests are much more identified with Europe than with the United States. In other words, American capitalism has a larger stake in Pan-Americanism than our neighbors. The war has changed this, it is true; but it has not essentially altered the situation, has not created a much larger community of interest. The reason thereof lies in the circumstance that the United States seeks to exploit the situation in the interests of Imperialism, instead of pacific Capitalism. American Imperialism does not desire a federation of the Americas, but exclusive opportunity for investment and exploitation in Latin-America, protected by the Roosevelt [Monroe] Doctrine and the weight of armaments. And unless the present Imperialistic tendency is checked by the counter forces of Socialism and democracy, the Monroe Doctrine and Pan-Americanism will merge as the definite international expression of American Imperialism.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1916/v4n03-mar-1916.pdf