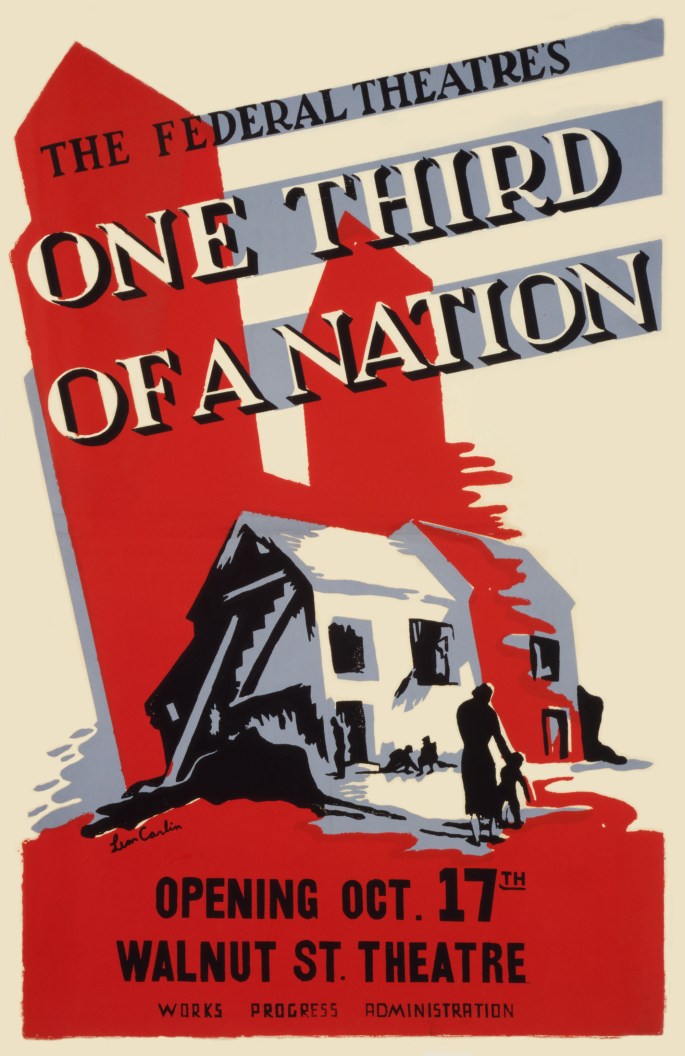

A glowing review of …one-third of a nation…, produced by the W.P.A. Federal Theatre Project.

‘The Federal Theatre Treats Slum-Clearance’ by Walter Ralston from New Masses. Vol. 26 No. 6. February 1, 1938.

THE Federal Theatre’s superb production of …one-third of a nation… reaches a new high in the Living Newspaper series. It gains by comparison with its successful predecessors a difficult test to survive. Combining the ample documentation of Triple A Plowed Under and the brilliant staging of Power, Arthur Arent’s incisive dramatic exposition of the housing problem makes a distinct contribution by linking an immediate social question to its historical sources, thereby adding a new and necessary dimension to the Living Newspaper. Not only is dramatic comprehension heightened by the depiction of two centuries of history, but also the audience’s capacity to discriminate between the futile remedial efforts of the past and the genuine solutions which that experience suggests. The Living Newspaper had already dramatized the headlines; it can now see beyond them.

The tenement-house set, a daring design by Howard Bay, is a permanent background for the historical drama. On its creaky landings and shabby fire-“escapes,” in its cubby-hole rooms and polluted basement, generations of trapped human beings enact their tragic lives. It towers over the stage, a hideous representation of the greed motive in capitalist society. The fire in the opening scene (1924) will perhaps destroy the structure, but it will devour human victims as well. And the ensuing “investigation” only serves to hush up the rotten dereliction. The fire scene is repeated at the end of the play. In between is portrayed an amazing record of graft, corruption, hypocrisy, cruelty, and downright degeneracy.

“Back into History!” cries the Loudspeaker at the opening of the third scene. “The mad scramble for land begins…Who owned it first? How did they get it? Who bought it? And above all, who made the profit?” Trinity Church got the first and juiciest slice from Lord Cornbury, who got it from Queene Anne, who got it, one supposes, from God. But the church parceled it out to parishioners like William Rhinelander. Prices skyrocketed. Astor got in on the ground floor. So did Wendell, Goelet, and those other profiteers whom Gustavus Myers has described in his History of the Great American Fortunes. All they had to do, with the benign endorsement of Trinity, was to sit tight and wait for the population to grow. Every corner of the carpet became priceless. The loot was in direct proportion to human suffering.

Clarence R. Chase, who does a fine job as the average citizen, Buttonkooper, is justifiably shocked when he is let in on these historical scenes. He is furnished with a guide and taken through the housing set-up of the forties, the sixties, and so on. He sees plenty: cholera, plague, malnutrition, the blood and filth of the slums. Buttonkooper wants an explanation. Why did they put up with this? What was done about it? There were, to be sure, investigating commissions, but they didn’t always tell the truth. And when they did, they were seldom backed up by the courts. Always there were legal loopholes of one kind or another. The dramatic scenes in the toiletless single rooms where whole families lived still went on.

But it would be a mistake to give the impression that all is gloom and despondency on the Federal Theatre’s stage. As the action unfolds, the protests of the tenants mount. One scene in a Harlem hotbox is particularly striking. Three Negroes take eight-hour shifts on the same cot, for which they pay triple rent. One young fellow is sick, but his fatigued co-tenant must either go sleepless or kick his friend out. Their expression of solidarity at the end, their decision to cooperate with other tenants in a strike is a glorious reversal of that train of abuses which has been making a nightmare of their lives.

Tenants’ unions are formed; there are marches on Albany; pressure is exerted on the legislature. And the need is finally recognized by the Roosevelt administration. But in Congress, Senator Wagner’s housing bill is whittled down by reactionaries, and in a fitting commentary, the Loudspeaker points out that the war appropriations are greater than the appropriations for this tremendous national need.

Merely to have stated the case for low-housing and slum-clearance projects so successfully would have been a welcome achievement. The Federal Theatre has combined with this statement some healthy laughs. We pity the victims of the tenement, but we also learn that their oppressor was a fraud whom we have allowed to get by through our own inertia. Buttonkooper, who after all represents the audience, decides at the end that things will not go on in the old way if only we get together to do something about them.

The punch of the play, it seems to me, lies not so much in our accumulated indignation at the landlords as in our indignation at our own easy tolerance. When we find Buttonkooper’s naïveté ridiculous, we are really, perhaps for the first time, seeing how absurd was our compliance to a situation which we inherited from the corporation of Trinity Church. And as Buttonkooper learns that those pious blusterers of Knickerbocker days were pulling the wool over the eyes of the poor suckers who were their contemporaries, he vows that he won’t go through the humiliating experience himself. Once he has learned that he has to get together with the fellow next door, he has started on the highway to a better life. That the Living Newspaper has pointed this lesson with careful evidence and witty candor the reader will discover for himself when he goes to see …one- third of a nation… It’s one of the few “musts” of the year.

WALTER RALSTON.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1938/v26n06-feb-01-1938-NM.pdf