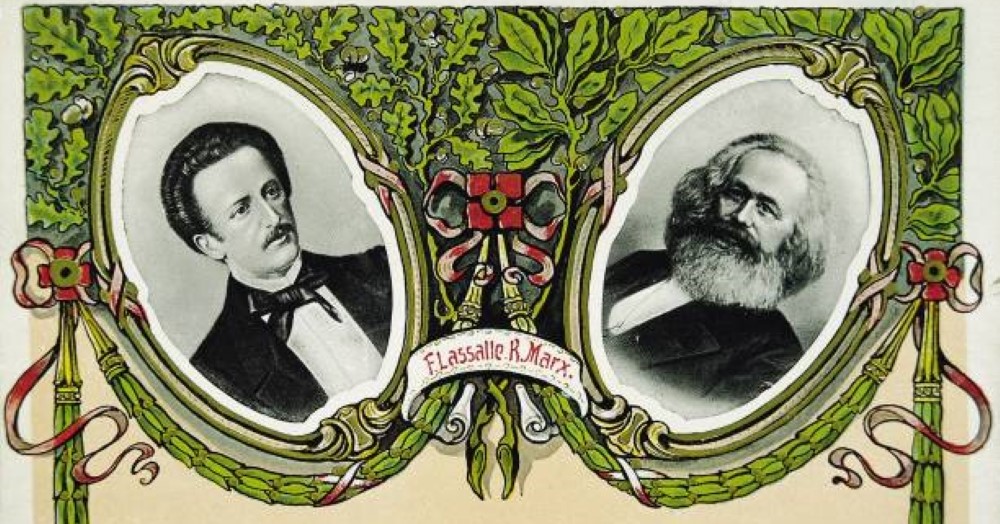

A valuable biography of the great working class leader. The U.S. version of Lassalleanism was the predominate political voice of the Socialist Labor Party until the ascendancy of Daniel De Leon in the mid 1890s.

‘Ferdinand Lassalle: A Brief Sketch of the Life of the Immortal Thinker’ from Workmen’s Advocate (New Haven). Vol. 5 No. 35. August 31, 1889.

Ferdinand Lassalle, though the son of a modest silk merchant, nevertheless, led a life of the greatest public activity. He was born at Breslau, April 11, 1825, and his parents naturally intended that he should become a merchant also; and the wealth at his disposal, together with the opportunity of succeeding to a well-established business, certainly would have had attraction for a less brilliant character. But Lassalle began early to interest himself in the classics, and Heine’s works had a peculiar fascination for him. He dreamed of becoming a great poet, and the democratic ideas of Heine were his models. His parents reluctantly listened to his importunities for a higher education, and finally, at the age of eighteen, sent him to the Breslau University, which he soon exchanged for the University of Berlin, where he industriously studied philology and philosophy. His restless spirit was not satisfied with learning only; he must work; and although he had not yet given up the idea of becoming an author of prominence, he could not succeed in his efforts in this direction. His manner of living was luxurious, and his family paid the bills, though they strongly objected to his extravagance.

After finishing his studies at Berlin in 1844 he went to Düsseldorf, and then to Paris, in both of which places he still pursued his favorite studies. In Paris he made the personal acquaintance of Heinrich Heine, who, skeptical as he was, acknowledged his admiration for Lassalle with wonder. He once wrote him: “You have a right to be bold. In comparison with you, I am but a modest fly. I love you much; not to would be impossible, for you tease one till he loves you.” Heine welcomed Lassalle as a fortunate acquisition of contemporary time. On ending his studies in Paris he again went to Berlin to settle down as a private tutor and lecturer to students at the University, where he enjoyed the friendship of such important personages as Alexander von Humboldt, the naturalist, and Boekh, the philologist. It was at this time that he became acquainted with the luckless Duchess Hatzfeldt, whose husband treated her with such cruelty, and which led to the celebrated case before so many courts, in which Lassalle vigorously defended the sorely persecuted woman who was forcibly parted from her children. This connection led to many persecutions of the young lawyer himself, and his servant was bribed to forswear himself and accuse his employer of advising friends to commit theft. It was in his defense of himself and friends that Lassalle made the great speech which attracted the attention of all Europe, after which he was declared not guilty, and carried to freedom amid the applause of the multitude.

During the memorable year of 1848, Lassalle once more entered political life. It was at this time that Freiligrath wrote his famous poem, “The Dead and the Living,” for which he was arrested August 28, 1848. But Lassalle was at work among the people, and such a public sentiment in favor of the imprisoned poet was engendered that it influenced the jury, and on October 3 the great poet was liberated.

The authorities, however, feared the bold tribune, and sought to put him out of the way. So on the 22d of November he was arrested on the charge of “persuading the citizens to arm themselves against the king.” The trial was purposely lengthened, new charges added, and finally, after a year of prison and court-room life Lassalle was allowed to go free in the winter of 1850-51. Then he continued the great case of the Baroness Hatzfeldt until victory crowned his efforts. His client never deserted him, and they lived together in Düsseldorf. Lassalle, however, with new means at hand, played spendthrift in his private life. Finally he made Berlin his home, and for a number of years there was rest for him so far as active politics was concerned. He continued to work, however, and his ideas were already ripening into socialism, for he had long been acquainted with the writings of Marx and Engels. About this time he completed his principal literary work: The System of Acquired Rights” (Das System der erworbenen Rechte), in which he attacked the principle that the existing social order, with the rights and laws which find their source in it, must be sacred for all future time; holding, on the contrary, that every period had the right to decide, not being under the denomination of the past, and, consequently, not bound to recognize as right anything which antagonized its conception of right. In 1862 he wrote a philippic, abounding in withering criticism, against Julian Schmidt, the literary historian. In this year, also, he again mounted the rostrum to address the people during the constitutional campaign then agitating Prussia. The two great political parties looked upon him as a dangerous enemy, and he criticised them unmercifully, paying especial attention to the Progressists, whom he attacked in his pamphlet, “Might and Right,” in which he held that they had no right to speak of rights, since they accepted wrongs without opposition; rights were only to be found in true democracy.

In connection with Lassalle’s activity in these years, the last November’s number of Neue Zeit, published in Stuttgart, printed a valuable contribution anent the establishment of the Socialist Party in Germany. It is in the form of a letter, written by Lassalle to Dr. M. Hess at Paris, and dated August 17, 1863. In it he said:

LASSALLE’S LETTER.

“You know how I fared in the movement and how it came about. It is not a theoretical one, nor the consequence of a theoretical work, but a practical agitation. Had I written a theoretical, economic book I would have proceeded quite differently and advanced further. I was about to begin such a book when the possibility for practical work came to me from Leipzig. I almost hesitated to improve the opportunity, in view of the objective attractiveness of a systematic economic work, which I clearly saw would be forever withdrawn. from me by the agitation. But then I said to myself: How much has been written and proved already, and still almost forgotten by the world! Through such a book another advance in science, a nourishment of thought, would be achieved in from thirty to fifty years. Here, on the contrary, was the incentive to a mighty action affecting the whole nation. It meant that while the German slow-coaches à la Schulze-Deutsch believed every socialist thought dead and buried, they should suddenly see socialism arise as if by magic in the form of a political party, and that was the cause of their great astonishment.

“A theoretical movement and a practical movement differ in this: The former, to be of value, must prove the consequences of a principle, and to the last stage if possible; and the more a book fulfills this demand, the better it is. In the case of a practical movement, however, one must throw himself upon the immediate sequence–the first practical, possible step, in which the whole principle is embraced, involving a decided accentuation and a sharp theoretical exhibition of the same. In this way the masses are proffered something definable and tangible on the one hand, while, on the other hand, many good-natured people with only partial insight are won. At any rate, something practical and possible is set up as a goal, exciting more intense opposition than if one made demands carrying more extensive consequences which do not for the moment threaten danger.

“Since I went to work on this idea, I think I have achieved the great success which is now part of the history of our movement. For, no matter what our numerical strength, such a success is not to be wiped out by denial. It exists in the unparalleled excitement which has seized all Germany.

“Without desiring to belittle the merits of Marx and the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, I think I may presume to say that now, for the first time, a socialist party exists in Germany, which has a political significance and represents a mass.”

And it was this practical side of Lassalle’s activity which has contributed so materially to the importance of the Socialist movement in Germany. It was the presentation of a precise program, a goal possible of attainment, which left out of account for the nonce mere numerical strength, which made success possible, nay, sure. It was the fact that a socialist party had entered the political field which constituted the success, not the number of votes cast. It was the fact of successful political organization which laid the foundation for future action, and, finally, after years of practical endeavor, made the political movement of the German Social-Democracy what it is. For us in America there is little doubt as to what Lassalle’s position would be were he among us in the vigor of life.

Of Lassalle’s private life it is of no particular advantage to speak, and it offers no practical suggestions in the line of our movement. His loves and passions and his social predilections were matters concerning which there can be no positively correct opinion formed. What little has been given to the world would show him to have been erratic and, from a prosaic standpoint, even silly. It was a love affair which led to his death A duel with a rival, who succeeded by intrigue in obtaining the hand of a lady with whom Lassalle imagined he was in love. The duel took place near Geneva, and Lassalle was mortally wounded on first tire, though he lived two days after the affair. His remains were buried in the Hebrew Cemetery at Breslau. The grave is marked with a modest stone, upon which Is inscribed:

“Here rests what was mortal of

“Ferdinand Lassalle

“The Thinker and Warrior.”

He lived not in vain, nor did the great movement which received the impetus of his activity end with his life. The socialist workmen honor his memory, and on each anniversary of his death bedeck his grave with garlands.

The Workmen’s Advocate replaced the Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement and the English-language paper of the Socialist Labor Party originally published by the New Haven Trades Council, it became the official organ of SLP in November 1886 until absorbed into The People in 1891. The Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, published in Detroit and New York City between 1879 and 1883, was one of several early attempts of the Socialist Labor Party to establish a regular English-language press by the largely German-speaking organization. Founded in the tumultuous year of 1877, the SLP emerged from the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, itself a product of a merger between trade union oriented Marxists and electorally oriented Lassalleans. Philip Van Patten, an English-speaking, US-born member was chosen the Corresponding Secretary as way to appeal outside of the world of German Socialism. The early 1880s saw a new wave of political German refugees, this time from Bismark’s Anti-Socialist Laws. The 1880s also saw the anarchist split from the SLP of Albert Parsons and those that would form the Revolutionary Socialist Labor Party, and be martyred in the Haymarket Affair. It was in this period of decline, with only around 2000 members as a high estimate, that the party’s English-language organ, Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, appeared monthly from Detroit. After it collapsed in 1883, it was not until 1886 that the SLP had another English press, the Workingmen’s Advocate. It wasn’t until the establishment of The People in 1891 that the SLP, nearly 15 years after its founding, would have a stable, regular English-language paper.

PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90065027/1889-08-31/ed-1/seq-1/