Many thousands of Punjabi Sikh’s came to California as contract laborers around the turn of the last century. At first to cut lumber and build rail, later primarily in agriculture. Already well established communities existed at this writing when Taki Singh Rai, a student at U.C. Berkeley, gets a summer job with fellow Indian worker at a Marysville ranch, where twenty years earlier all Indian workers had been driven from town.

‘Hindus Enslaved, Treated as Cattle on California Ranches’ by Taki Singh Rai from The Daily Worker. Vol. 6 No. 56. May 13, 1929.

(By a Worker Correspondent) BERKELEY, Cal. When the summer vacation came, I started to look for a job. I went from Southern California to as far north as Oroville. Finally I met at Marysville a countryman from India, who told me where I could get a job.

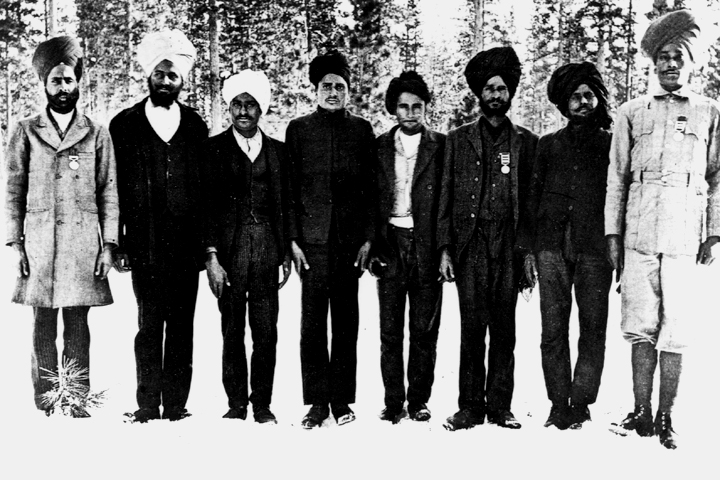

In the evening he took me to the ranch where he worked, which was only 10 miles away. Here I found housed in one of the ranch sheds six more Hindus.

After the usual introduction and hospitality of my countrymen, I was given the option of selecting any place for making my bed. I selected a small shed and moved there, after a week, which it took me to move cut the bones I found in it. My reason for moving out to another shed was in order not to disturb the other workers late at night while studying (I am a student).

From the time I reached that camp in the dark I felt myself thousands of miles away from civilization and in the position of a coolie in one of Lipton’s tea plantations.

Tired Out by Slavery.

My countrymen were so tired out after the day’s work of 12 hours that they had to prepare for the next day’s work with the strongest of liquor. After sleeping in those dungeon-like sheds for about six hours, everybody was rushing back and forth to get started by six o’clock to their assigned work at their usual goose-step speed.

I set out along with my fellow-workers towards the orchard. We started working and everybody began to inquire about me to get thoroughly acquainted, for they could not be very friendly the night before, when they were tired and looked like corpses. Working continued the whole day, with an hour’s interval until 7 p.m. Then I had become incorporated into the routine.

After some days I found a big Studebaker being unloaded in a shed, where nobody could suspect liquor. Everybody except me and another worker agreed to buy a gallon each. The boss directed a scornful look toward the fellow-worker who would not buy. After a few days that worker was fired for not contributing to the bosses’ royalties by buying booze.

A Rich Slave-Driver.

Since I was a student, my fellow-workers were sympathetic toward me and the boss had to excuse me. The owner of the ranch and orchard, a resident of Sacramento, had so many big ranches that he handed ever the management of each to a manager who decided what kind of work was to be done and how many workers should do it.

But he “had nothing to do” about paying them. The workers got their pay from the owner and had to spend a great deal of time and go to great trouble to get their pay. They had to go to Sacramento, where it was as a rule hard to find the owner.

Cheated of Pay.

There were many workers who had not been paid for three months, for whenever they went to Sacramento either they could not find the “Lord” or when they did get hold of him they got only “golden promises.” Seven of us used to send one who worked there for a long time, and he never succeeded in bringing back the real amount due us. Sometimes he came back with nothing but the promises, which were never kept. Some of the workers tried to take up the matter with the labor commission, at the expense of losing their jobs. They had to go from town to town hunting the labor commissioner, wasting their money.

Served Filthy Food.

In addition to their lodging in tarn-like huts, the situation of the workers is miserable, for they were exploited terribly. The ordinary food they get and for which they are charged $1 a day is never worth more than 65 cents a day. Flies on the food and overcooking is the rule of the place.

If any worker cares to object he is kicked out of the ranch. In order to hold the job the worker must be faithful to the boss. The bosses have taken advantage of the presence of so many nationalities among the workers to increase the hours.

A Scheme to Lower Wages.

One scheme of the bosses is to tell the workers they are about to employ Mexicans or Filipinos on the job, who, the bosses claim, are anxious to work for 10 cents an hour less than we are paid. By this system the bosses are enabled to pump out of the slaves more “presents.” The impression of California given by the papers, even in distant parts, is one of a land of Arabian Nights.

The papers do their job of serving the bosses well, for by attracting workers from all over with tales of many workers wanted, the wages are beaten down.

All this has changed my opinion of this kind of a society which causes so much slavery and misery.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n056-NY-may-13-1929-DW-LOC.pdf