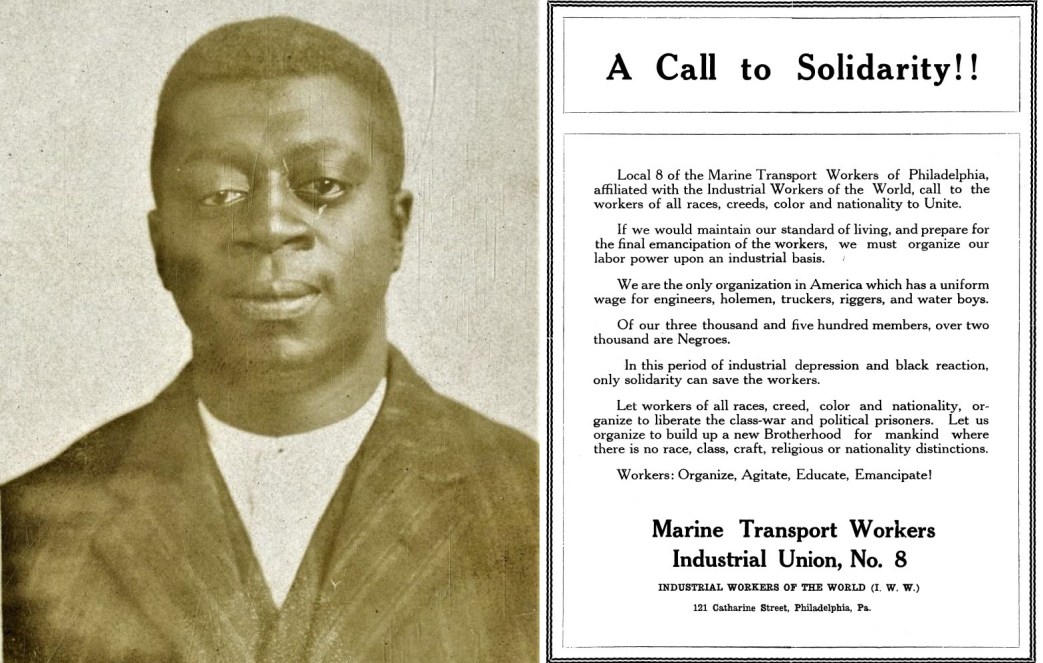

The Messenger visits a meeting of Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union Local 8 as they build and inter-racial union on the Philadelphia waterfront, an extreme rarity in the East at the time.

‘Colored and White Workers Solving the Race Problem for Philadelphia’ from The Messenger. Vol. 3 No. 2. July, 1921.

IN the city of the Quakers, the Southern bugaboo, the contact of Negro and white peoples, has been routed by the plain, unvarnished workers. In the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union, No. 8, there are 3,500 men, three fifths of whom are Negroes. During the war there were more than six thousand men in the organization.

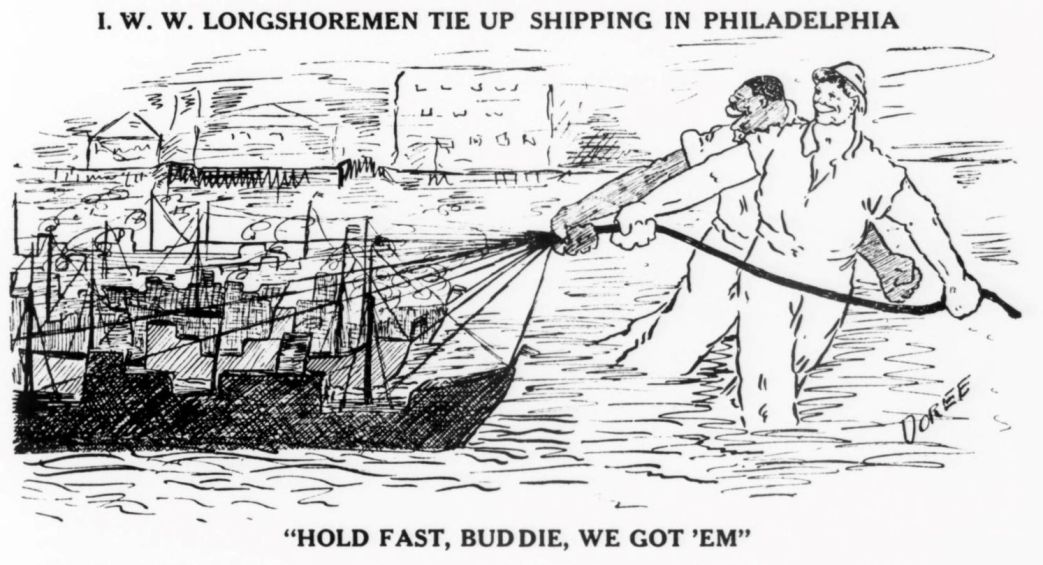

Despite the affiliation of Local 8 with the I.W.W., no attempt was made during the war to destroy the organization, doubtless due, so it is rumored among the men, to the recognition by the boss stevedores of the fact that the union had the power to tie up the port of Philadelphia.

Another signal achievement to which the men point with great pride is that no mishaps, such as explosions of any kind, occurred in their port–one of the largest and most important ports in the country, during the war, from which munitions and various materials of war were shipped to the Allies. Yet, malicious propagandists have sought to stigmatize these men as “anarchists” and “bomb throwers.”

Again, the organization has been the lever with which the men have raised their wages from 25 cents to 80 cents and $1.20 per hour. They have also established union conditions on the job. They have overthrown monarchy in the transport industry of Philadelphia, and set up a certain form of industrial democracy, in that the boss stevedores and the delegates of the union confer to adjust differences that arise between the longshoremen and the shipping interests. This is quite a long way from the day when the boss stevedores hired and fired, and reduced wages without let-up or hindrance. Then chaos reigned on the waterfront. The longshoremen had no power because they had no organization.

“But times have changed,” so one of the men assured us with a twinkle of triumph in his eyes; seeming at the same time to imply that they would never again return to the old conditions.

“We have no distinctions in this union”–another vouchsafed. “Everybody draws the same wage, even to the waterboy.”

At this time, our interesting confab with the different workers standing around in the hall, was abruptly cut short by a sharp rap of a gavel re-enforced by a husky voice, calling for order. Men were seen, in different parts of the hall scamping for seats. As we turned and looked to the front of the hall, we observed two workers, one black and one white, seated upon a platform. We inquired of their functions, and were informed that the colored worker was the chairman and the white worker the secretary.

The chairman was direct and positive and yet not intolerant. The meeting proceeded smoothly, interrupted here and there with some incoherent remarks, giving evidence that John Barleycorn was not dead. This was taken good-naturedly, however, as the worker, in question, was known as a good union man.

The most interesting phase of this meeting was the report of a committee on a movement to segregate the Negroes into a separate union. Strange, to say, this move came from alleged intelligent Negroes outside of the union, who have heretofore cried down the white union workers on the ground that they excluded Negroes from their unions.

It is interesting to note, in this connection, that the white workers were as violent as the Negroes in condemning this idea of segregation. All over the hall murmurs were heard, “I’ll be damned if I’ll stand for anybody to break up this organization,” “It’s the bosses trying to divide us,” “We’ve been together this long and we will be together on.”

Finally a motion was passed to adopt a program of action of propaganda and publicity to counteract this nefarious propaganda to wreck the organization upon the rocks of race prejudice.

Here was the race problem being worked out by black arid white workers. They have built up a powerful organization–an organization which has been the foundation of a good living for the men. Many a man told us that he had been able to maintain his children in high school on the wages Local 8 had secured for him, and at the thought of anyone attacking the organization, his eyes flashed–a hissing fire of hate–regarding such an attack as an attack upon his life and the lives of his wife and children.

Colored workers told us, too, that they remember when a colored man could not walk along the waterfront, so high was the feeling running between the races. But now all races work on the waterfront. Negro families live all through that section. It is a matter of common occurrence for Negroes and white workers to combine against a white or a black scab.

And the organization, Local 8 of the Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union did it all! The white and black workers were then pulling together. Why should they now pull apart? What they have done, they can do, and even more, if only the workers of races realize that their power lies in solidarity–which is achieved through industrial organization.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/1921-07-jul-mess-RIAZ.pdf