Relief kitchens, child care, and dances. Fascinating details of the exemplary work of activists in providing relief, information, and a new social life for destitute workers on a long, hard strike in Little Falls, New York waged by the I.W.W. Ideas that would be welcome home at any strike today.

‘Efficiency in Conducting a Strike’ by Frank Dawson from Solidarity. Vol. 4 No. 9. February 22, 1913.

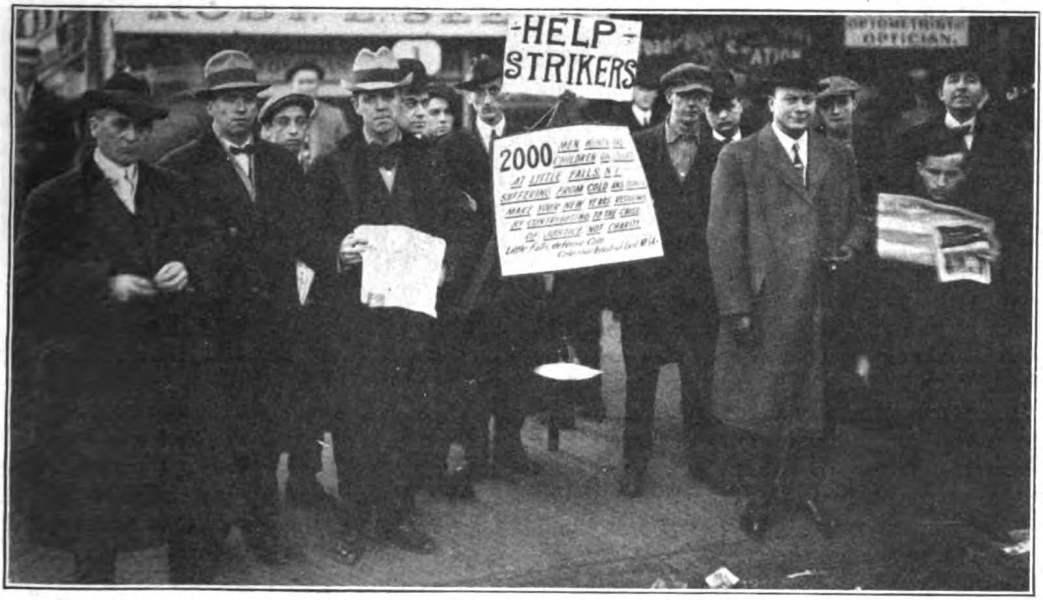

How the I.W.W. Organized Relief and Other Work at Little Falls

Revolutionary movements, like other forms of life, suffer from the inexperience of youth. The I.W.W. is not, nor has it been in the past, any exception to this natural law.

It is therefore with keen pleasure that I write of the Little Falls strike from a new viewpoint which we shall have to pay much more attention to in the future than we have in the past.

This viewpoint is that of efficiency.

Little Falls was not merely a successful social revolt. It was more. It marked an epoch in the conducting of strikes; an epoch of scientific management of strikes, so that waste is eliminated and the hard won money of fellow workers is not prodigally cast forth.

The early days of the strike I shall pass over cursorily. The readers of Solidarity are already familiar with the roots of discontent, from whence prang the strike. They are already familiar with the story of the organization of the strikers under the banner of the I.W.W. They are familiar with the brutal clubbings, false arrests, false imprisonments and generally “American” police methods adopted to force the workers back on the job. To speak of Russia is absurd The American policeman with his night stick and pistol is quite as bloodthirsty as the Russian Cossack equipped with a rifle. The I.W.W. publications have repeatedly and adequately told about these things. For me they shall be taboo.

RELIEF WORK.

It was after the strike had been in progress some time and the specter of hunger was daily becoming more menacing that the foundation was laid for the relief work, which will become a model for future strikes.

Strikers must be fed. That is a simple but none the less essential truth to remember. It was remembered in Lawrence, but the commissary there was organized in such a crude, haphazard, go-as-you-please style that it was impossible to tell how much this branch of strike activity was costing. Not so in Little Falls.

It fortunately happens that Schenectady contains a Mrs. Kruesie. Mrs. Kruesie, whose husband is socialist charity commissioner in Schenectady, has a great amount of practical experience in the organization of relief work. To this she adds a thoroughly class conscious revolutionary spirit. She went to Little Falls to see what could be done and perceiving that the chief strategic point was the soup kitchen she took it in hand. Her maxim was, Organization Means Success. The result of her investigation and work she published in the Schenectady Citizen. I cannot do better than quote from her article. She says:

“During the first 10 days the number of meals served to unmarried strikers was 696. The number of grocery orders filled for married strikers was 130. What did we weigh and pack for each family of five as a fair amount for two days? Two pounds of bread, one pound of pork or lard, half a pound of tea or coffee, one pound of imported macaroni, one pound of prunes, one cabbage, one cake of soap.

“The cost of this was about $1 at wholesale prices and the method was a great advantage over that of giving orders for 50 cents on local stores, which had been issued daily to each striker Previously the wasteful method of 50 cent tickets had been in vogue. I need not dwell on the leakage from this source alone in a large strike. It is to be hoped that other strike committees will copy.

“What sort of meals did we serve? Breakfast at 9 o’clock after picketing, consisted of unlimited quantities of bread, butter, coffee, milk, sugar, herring or fat bacon or apples. Dinner at 2:30 o’clock before the strikers’ meeting was a pot roast with potatoes, or pork and beans and cabbage, or a stew of good meat, onions, rice, potatoes, with tea or coffee and prunes or bananas. The cost of each meal was 7 cents.”

In depreciation and explanation of this low figure Mrs. Krueste remarks: “We had no rent to pay and no wages, but even then we are proud of ourselves for giving people all they can eat at such a price.” Supplementing this report, I would say that there were but two meals a day. A card-filling cabinet was installed and every striker in receipt of relief was given a card. Every meal time the card was punched. Duplicates were kept in the kitchen. By this means it was possible to tell whom you were feeding, and how many you were feeding, and so at any time we were able to calculate the cost of the kitchen. When Miss Matilda Rabinowits, who became famous as the girl who was no bigger than a pint of cider, but who carried dynamite in every fibre of her tense little body, first came to Little Falls she gave all her time and attention to the relief work. As a result, a well conducted clothes bureau was established and a shoe repairing establishment set up. No possibility was overlooked. With the coming of the cold the necessity for coal relief stared us in the face. It was met by patting one man in charge and making the strike committee sole dispenser. The necessity for this branch of relief I need not dilate on, Everyone knows that the keen frosts and biting winds of North America are wondrous strikebreakers.

The work in the kitchen was done mainly by strikers. Experience has proven, however, that when dealing with a type of strikers such as constituted the Little Falls revolting outpost it is well to have some thoroughly class conscious, patient, strong, impartial character in charge. For we found that not only were the strikers lacking in executive ability, but in many cases their prejudice, subjected to such a strain as a strike implies, was too strong to be overcome immediately by the newly implanted sentiments of internationalism. After repeated failures and bitches we heaved a happy sigh of relief when the blind baggage shot off Tom and Charley, both fellow workers from Minneapolis, Minn. Of course in many cases local talent can be found capable of running economically and without friction a soup kitchen. But be sure about it.

One form and a very important and new form of relief is the sending away of children.

Not only does it relieve destitution and poverty, but it hardens the fathers and mothers left behind and stirs into motion the slowly growing social conscience. The day after the children’s departure from Little Falls the newspapers devoted columns of precious space in a vain effort to prove that the children sent away were not strikers’ children. Why? They feared the public. That is why. More than one handkerchief was in evidence that morning and more than one eye glistened suspiciously. In order to prevent the thugs and cops getting one on you it is well to have papers drawn up by a fellow worker lawyer to show that the parents’ consent has been obtained to the exodus

Probably many of those who read about the beatings inflicted by the special thugs from the East Side of New York wondered what was done to alleviate the pain. To meet this situation a doctor was retained by the strike committee. Any morning between 7 and 8 o’clock, in the surgery, could have been seen strikers suffering from contusions, bruises, split heads and the floor bespattered with blood.

The last thing I will say about relief work will be to plead for rigorous attention to getting a competent fellow worker with executive ability to take charge of the finance. Little Falls strikers owe more than they realize or are capable of realizing to the conscientiousness and care taken by Miss Matilda Rabinowitz.

PUBLICITY WORK.

After relief work comes publicity work, that section devoted to sending messages from the front to those waiting anxiously for news. Never before, considering the number of people on strike and the local conditions, has a strike been so well chronicled as was the Little Falls strike. The outside world knew through more channels, was stirred to indignation more frequently at the brutalities, the inhumanity of the police of Little Falls than is usually the case in these industrial battles. In addition to that the facts necessary to put into operation the “due process of law” were collected ably and with systematic thoroughness.

The result of this work was to make our case absolutely water tight and, incidentally, *very incidentally, cause a state inquiry to be held.

This work was done by the organizers and the publicity man, Phillips Russell. To Russell’s good work is due the newspaper articles. To Benj. Schrager, Polish organizer from Chicago, we are indebted for the investigation into housing conditions, which was conducted by the State Department of Labor, who were quite surprised to find that the East Side of New York had much to learn on the gentle art of slow execution from the South Side of Little Falls.

To Schrager’s executive ability and indefatigability we owe the 100 affidavits testifying not to what the police did do, but to what the polies did not do. From day to day through the columns of the New York Call and weekly through Solidarity and monthly through the International Socialist Review were sent forth the only true accounts of what was happening in the jungle of New York state. Only Sebrager’s cool, calm, unwearied, perfectly balanced executive powers made this possible. Others, it is true, contributed their small tributaries to his broad stream. But they did no more. Was a Dan clubbed on the picket line? He noted it. Were unspeakable housing conditions brought to his notice, he investigated them. Did the state board of labor want facts, he had them. Not excited, never apathetic, never wearied, always on the job. That was Schrager; and we all came to love the sight of his gray coat, which was an inseparable part of him. He had brought it from Chicago, and it bore evident traces of much traveling.

To sum up: In publicity work, to be effective, you must be absolutely sure of your facts. You must have many of them. You must know how to use them; know when to be silent, and when to be loquacious. And keep the enemy on the run. Keep him guessing. Make him show his cards. Reserve yours.

SOCIAL LIFE.

The noticeable feature that impressed on the strike investigator in Little Falls was the splendid spirit prevailing, the splendid enthusiasm, the splendid solidarity. On cloner observation this was seen to spring from two interrelated sources. One I have dealt with. That was the keeping of the strikers in good physical health by a well organised relief department. The second source was the cultivation of solidarity among the strikers.

Those who have been on strike or suffered under the sting of the lash of enforced idleness; when that idleness meant potential descent into the lowest depths of the social abyss, know the misery and dispiritedness which drives strikers back to work when they attempt to fight the battle alone and with no other support than perhaps a moral conviction. A vision, confined wholly to pinched faces and intense suffering due to striking, is not conducive to producing and maintaining militancy and revolt. The realisation of this fact caused the establishment in Little Falls of dances, entertainments, amusements anything that would draw together the strikers in a bond of social interest. Once inaugurated the immense possibilities were seen and utilized as much as possible The love of children was given a class consciousness by having a grand Christmas tree and candy distribution on Christmas night. The value of friendship was emphasized by making everybody from Schenectady speak to the strikers even if they only said Good Night. The effects were obvious. The strikers’ hall became the center of strike life. bonds of economic friendship were strengthened and the bonds of differing religions, differing nationalities, differing customs and traditions were weakened. The organisers, mixing among these assemblages bringing all their joys and sorrows to these mass demonstrations or gatherings won the love and gained the trust of the “wops” and “poloks” and “dagoes” who never before knew what equality meant. It was wonderful, this growth of a new morality. Right there in a dingy, small ugly hall, this new morality was being woven.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1913/v04n09-w165-feb-22-1913-solidarity.pdf