Ed Moore with a superlative look at a labor movement radicalizing and in transition as the Baldwin Locomotive Works strikers find common cause with the striking Philadelphia trolley lines.

‘The Strike at Baldwins’ by Ed. Moore from International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 2. August, 1911.

A TEST of strength to decide whether all the men who build locomotives shall continue to be employed, or whether some of them shall be thrown out to starve when orders fall off was the cause of the general strike of 12,000 men against the management of the Baldwin Locomotive Works in its plants in Philadelphia and Eddystone. Eddystone is just outside of Chester, Pa.

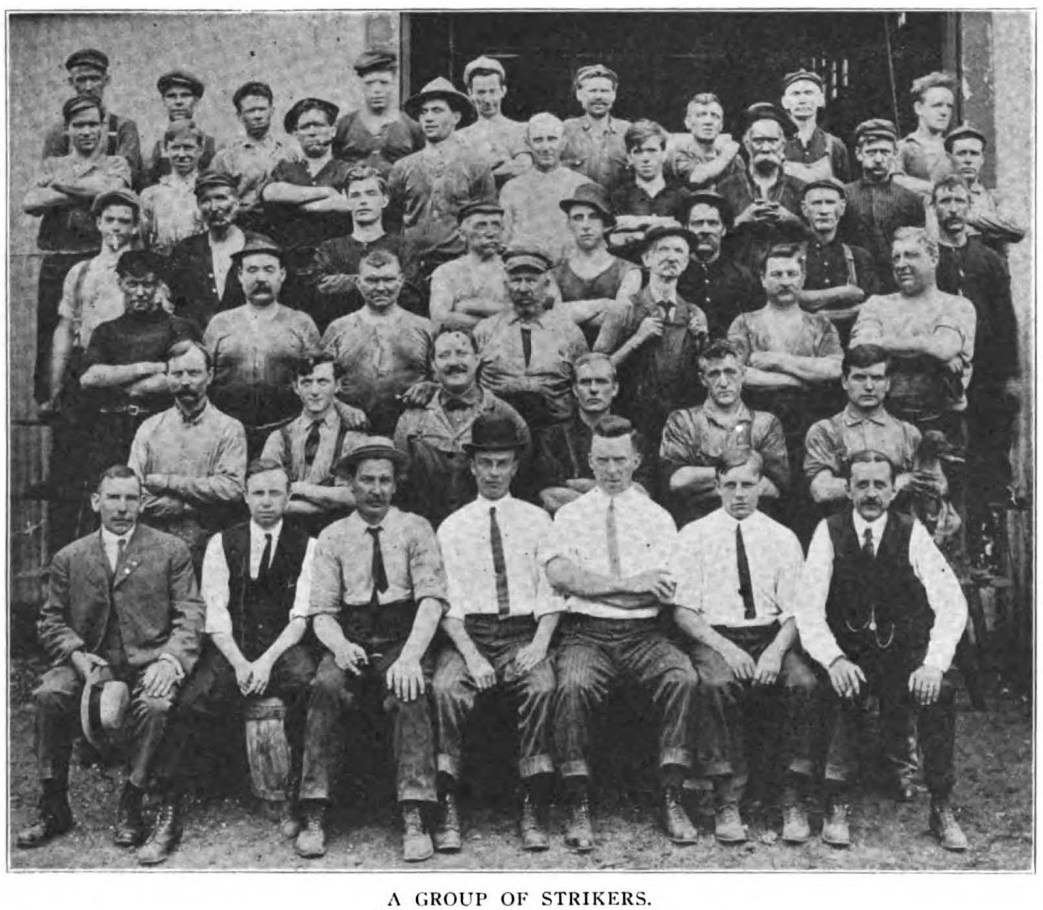

Thirteen different craft unions, federated in the Allied Council of Locomotive Builders, all its members employed in the Baldwin plants, laid down their tools and walked out on strike for the purpose of forcing the general superintendent to order the re-employment of 1,200 men who had been laid off. Most of the men had been picked out, as the general superintendent admitted, because they were openly and boldly active in pushing the work of organizing the locomotive builders and teaching them that profits come out of that part of the work in building locomotives for which the employes receive no money.

“The Hell Hole of Philadelphia,” is what the Baldwin Locomotive works is called in the City of Brotherly Love. For years every effort to get the men employed in it to form or join a union failed. From ten to twenty thousand accidents occur there every year and in hundreds of cases the victims die from their injuries. Apparently this state of affairs made no impression on the fortunate ones who recovered and who were permitted to return to work, nor did the deaths from the fatal accidents seem to be a warning to all the employes of what was likely to be their fate at any moment. But expanding industry—business growing larger—works in mysterious ways its educational mission to perform.

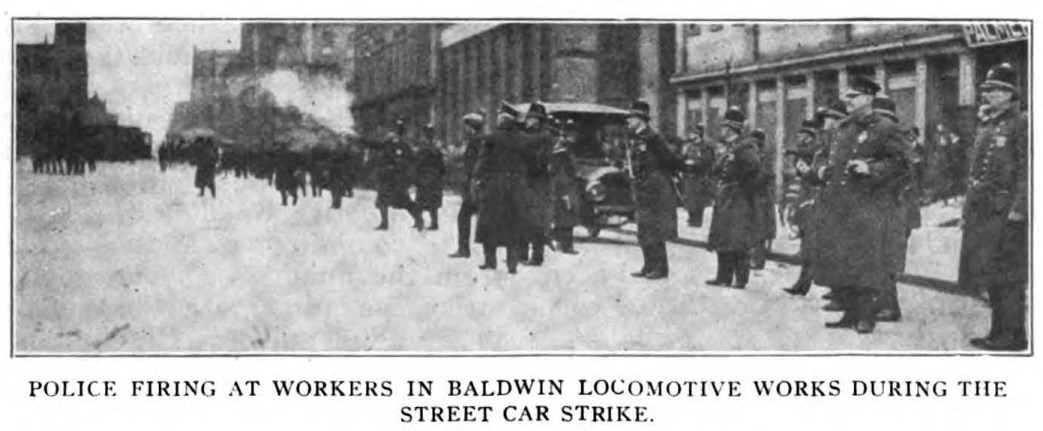

In February, 1910, the motormen and conductors of the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, which operate all of the street railways of the city, struck in retaliation for the laying off of several hundred union carmen without a moment’s notice by the company.

Using the sentiment created by the Socialist party for unity of action by the workers, a clique of trade union politicians, in a spirit of bravado, and to make a bluff to frighten the businessmen, who give the capitalists’ orders to the politicians of the old and reform parties, to make them place union labor leaders as candidates on the capitalists’ tickets, declared they would call a general strike of all the workers in the city if the Rapid Transit Company did not make a settlement with its striking employes.

Unions not affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, and shop associations, some of them formed on the spur of the moment, forced the hands of the bluffing trade union politicians, and, in the wave of class-conscious enthusiasm which swept the city from its conservative moorings, the workers in the Baldwin shops became the smashing shoulder that shivered the bulwarks of the traction company.

Taught their own power by standing shoulder to shoulder to help the trolleymen, the Baldwin workers agreed, while still out fighting for the trolleymen, that they would organize for their own benefit. While in this state of mind, business agents and organizers of the craft unions prejudiced their minds against the Industrial Workers of the World by insinuating that it is the same kind of a union as the Keystone Union, an association of scab trolleymen that the Rapid Transit Company has organized. To keep the ranks of the strikers unbroken, the Industrial Workers of the World, while denying the lying accusations of the craft union officials encouraged the Baldwin men to organize, preferring to see them united in some kind of a union rather than to let them remain unorganized, with each individual at the mercy of the spiteful little bosses. By boasting of the large membership of the A.F. of L., and its financial resources to aid its members in their strikes, the Baldwin men were induced to go into thirteen craft unions. But the idea of one big union had taken such firm root in their minds that it forced the international craft unions to grant to their locals a dispensation to let their members form a locomotive builders’ council. In all matters affecting the Baldwin shops the Allied Council of Locomotive Builders has jurisdiction. It set its face against paid business agents, and it does its work through unpaid committees.

During the year of its existence, the Council has done remarkably good work by shortening the hours of labor—securing Saturday half-holiday—and in getting an increase in wages. It was preparing a new wage scale, and to make sure of its acceptance by the Baldwin Locomotive Works, the several unions in the Council vigorously pushed the work of getting those not members to join them. At the noon hour, the committees went from one department to another exerting moral pressure, sometimes with physical force, on the non-unionists.

A workingman in one of the departments committed suicide, and the charge was made and posted in conspicuous places in the works, that he was driven to it by the insistent demands of the union men that he should become a member. This charge made the union men indignant, and as several of their number had been fatally burned in a preventable accident only a few days before the non-unionist took his own life, they compared the hushing up of the details of the killing of their fellow-unionists with the loud outcry about the death of a man who took his life with his own hands.

Indignation ran high. The boldest among the men wanted to lay down their tools at once and remain idle until the insulting notice was removed. Advised by those who thought it best not to be too ” radical, the insult was swallowed. Before the smart from the sting of the insult had ceased to hurt, committeemen and active unionists were laid off. A falling off of orders was the reason given for laying off 1,200 men. That the company was lying was evident to the men when they were told that they would have to take off their union buttons Unionism and not slack work was the reason the men were laid off.

The Machinist Union in the plant was hit the hardest. At a meeting, it instructed its president, who was one of its delegates to the Council, to insist that a demand should be made that the victimized men should be re-employed. One of the discharged active union men had been a trusted employe of the company continuously for thirty years.

Remembering the big promises of the international unions, and anxious to get the financial assistance they promised to give any of their members who should be forced to strike, the Council called in the presidents of the international unions. These officials, while very generous with words of sympathy for the victimized men, said that in view of the business conditions they would not sanction a strike, and they succeeded in persuading the Council to take no action.

Because he had disobeyed its orders, and because it believed that it was mainly through his influence that the Council accepted the suggestion of the international officials not to order a strike, the Machinist Union deposed its president.

Feeling assured that it had the men beaten at every point, the Baldwin Locomotive works took advantage of the refused support of the international unions. There came a sudden change of front in the manner of General Superintendent Vauclain from sympathetic consideration to a proud and insulting manner. His taunt was that if the men struck hunger would bring them back to the shops. Baldwin’s thought they could slip over a knock-out blow. They aimed in the stay bolt shop. This shop is in the boiler-making department, in which the most aggressive union men work. A foreman was discharged because he would not take off his union button. A number of his men went out with him. This started the stampede which, for all practical purposes, closed the plants in Philadelphia and Eddystone.

A factor, which may have been the predominating one in getting the men to stand together, was the police interference with Elizabeth Gurley Flinn. They had orders to interfere when she attempted to speak at the noon hour in front of the Baldwin Philadelphia plant. It showed the men on whose side the city government is, and they grasped the idea of One Big Union to get the best of the bosses.

One of the first acts of the men after coming out on strike was to take authority out of the hands of the Allied Council of Locomotive Builders and vest it in a strike committee composed of delegates from the unions. The members of the strike committee are the most radical men in the unions. By this act notice was served that the strikers were going to attend to their own business in their own way.

What was the most remarkable thing about the strike was its democratic management, and in a most intelligent manner, by men, who until they came out were unknown in the labor movement, and regarded by themselves and their fellow-workmen as incapable of doing big things. But they handled a situation that would drive a trained tactician from West Point insane, and a Kuraupotkin would have fallen back on suicide to get out of it.

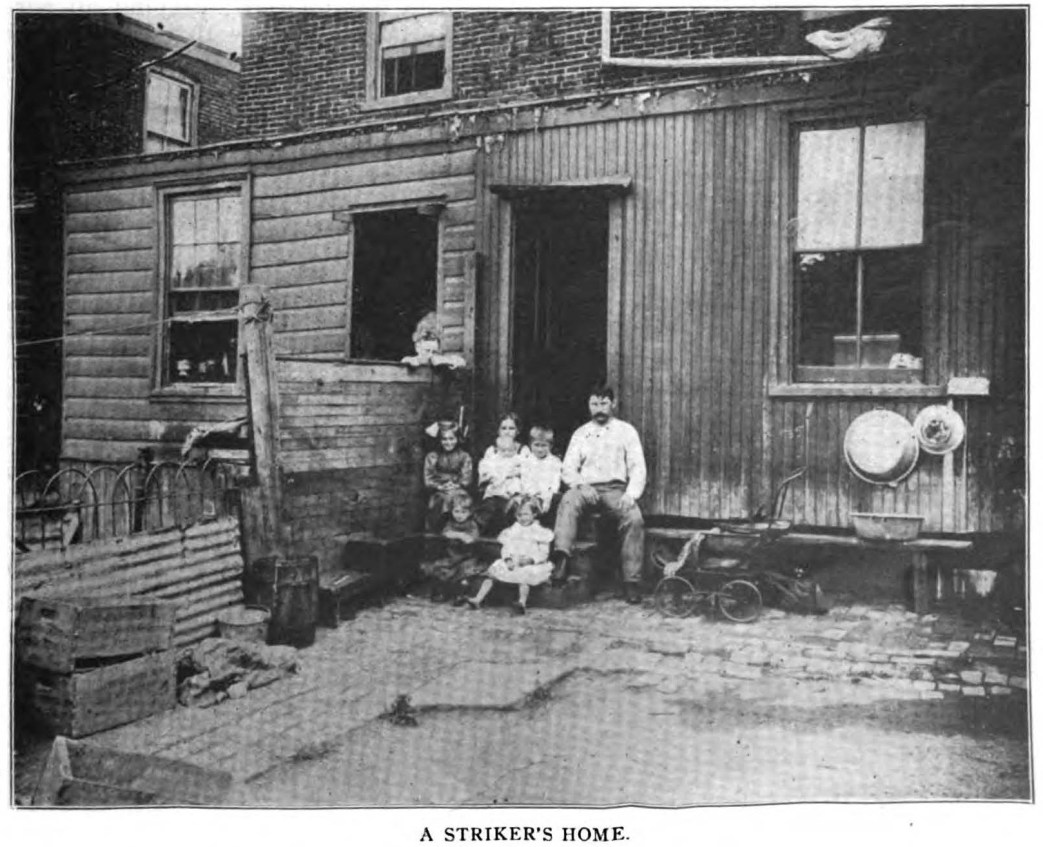

As soon as a relief committee was appointed on the first day of the strike, urgent demands for immediate relief were made. Look at the picture of the striker and his family. His own statement is that he had not made a full week’s time since the first of the year. He pays ten dollars a month for two small rooms and a little outside kitchen in a dilapidated house. It takes a large quantity of food to feed thirteen mouths, and this striker, employed only when the Baldwin works wanted him, owed two months rent, and the grocer had a bill of twenty-seven dollars charged against him. General Superintendent Vauclain told a committee while in conference on the proposition of taking back the men laid off, that if a strike was ordered the company would wait until hunger made the employes beg to get back. Mr. Vauclain is reputed to be a Christian gentleman. Humility is a Christian virtue. Poverty is its mother. Vauclain keeps his workers poor, and that, he thought, would keep them so low spirited that they would never strike.

To keep roofs over their heads, and to get food to put into the mouths of several hundred hungry families of strikers was what the relief committee had to do at once. Official sanction of the strike was refused by the international officers. The international president of the Iron Molders’ Union told striking molders at Eddystone to tear up their union cards, if ordered to do so by the Baldwin Company, and go back to work. In a situation as desperate as this, what would trained military experts have done? Would they have done as well as the relief committee of the Baldwin strikers? And what was it this committee did? On a suggestion from the local I.W.W., endorsed by Local Philadelphia of the Socialist party, collections to aid the strikers were taken up from door to door. Members of the Socialist party and of the I.W.W. acted as guides for the strikers who collected money, as the cards they gave out stated, to keep Morgan from starving them. At last the army of the working class has learned how to live by foraging in the enemy’s country. From the indications m the seamen’s strike, it will next starve the enemy in its own country, by a general strike.

A far extended picket line was thrown around the plants. So vigilant were the pickets that the workers in other industries in the war zone were often held up and made to prove that they were not strikebreakers. Every four hours the pickets were relieved, and a bicycle corps was on continuous duty, bringing in reports to headquarters, keeping all parts of the line in touch with what went on.

An ambitious politician, who wishes to be the next mayor, and his backers in the Department of Public Safety, did not dare to be too brutal, and as the strikers had friends in the neighborhoods where strikebreakers lived, and as these friends took good care of the “Heroes,” no open clash between the city government, the ally of the Baldwin Locomotive works, and the forces of the strikers took place. One striker, a Pole, was seriously wounded by strikebreakers. Charles Schorr, who said he was a special policeman for Baldwin’s, was killed in a quarrel that he started on a street car.

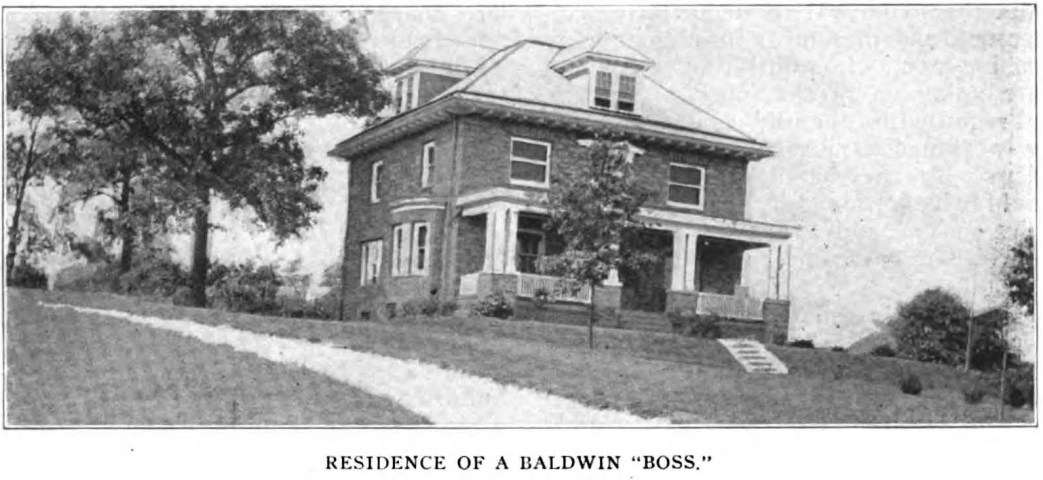

J.P. Morgan has put his fingers into the Baldwin Locomotive works’ pie, and the drawing of the plums from it is the probable cause of the trouble. Organized workers resist when the screws are turned too fast and the pressure becomes too hard in squeezing out their blood.

Under the Morgan scheme of reorganizing the Baldwin Locomotive works, at least $20,000,000 of water was added. As Morgan never takes less than fifty per cent of the spoils, he will probably get $10,000,000 of real money out of the deal. At five per cent per annum, this will give him $500,000 a year income from the labor of the locomotive builders in the Baldwin plants. A weekly tribute to him of $9,615.38, paid out of the wealth put into the locomotives built by the wage-slaves in a great American industry, all in the city where it was proclaimed “all men are born free and equal.” Look at the pictures of where the wage-slaves live, then look at the one of the home of the chief slave driver for Morgan in the Baldwin plants, and show us the equality and freedom that is the boast of our masters.

But we are on our way to freedom, marching on the road of industrial unity under the banner of One Big Union. We are banding together for revolutionary political action. We are calling the working class to revolt by the slogan: “Workingmen of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains; you have a world to gain.”

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n02-aug-1911-ISR-gog-Corn-GR.pdf