Art Shields, among the twentieth century’s finest labor reporters, tells the story of Edgar Combs, the last prisoner to be held from The Miners’ March, what we now call ‘The Battle of Blair Mountain’ in 1921. Shields was a a witness to the mine war and spent many years covering West Virginia’s labor struggles. Edgar Combs would be pardoned after a vigorous solidarity campaign, in part activated by articles like this, in early January, 1927. While in prison his wife Fannie lost two fingers to the owner’s bottom line in the mill which she was working.

‘The Last Prisoner of the March’ by Art Shields from Labor Defender. Vol. 1 No. 4. April, 1926.

EDGAR Combs, the last class-war prisoner from the lost battleground of southern West Virginia, used to work along Georges Creek, the little yellow mine water stream that tumbles down the narrow valley that cuts like a rut thru the mountain of Logan County. The coal seams here are rich but the coal diggers are very poor and live in the most squalid company houses I have ever seen.

These little tarpapered boxes in the creek bottom, set on stilts over the puddles that gather after a rain — the children bare-legged in the winter cold — the murmur of mothers complaining that the store has cut off their credit and there is no food in the house the day before payday — the thugs loitering by on their masters’ business — all these commonplaces of Logan County will aid the stranger to understand, perhaps, what moved Edgar Combs and several thousand comrades, in that historic week of the summer of 1921, to set forth in the armed march that was intended to end the tyranny in the open shop counties.

Edgar Combs is now No. 13381 at Moundsville. They sentenced him in the Logan courthouse, where Judge Bland ran the court martials for Don Chafin, to 99 years. Combs was denied the change of venue to another county granted other union men held on charges of murder and treason. The Logan authorities had it in for him especially because this prisoner of war used to be a Logan man, who might have been with them, but was against them. He had been, for a time, a boss worker, a contractor, and what business had he to fight the operators! He had even been offered a deputy’s post, and graft, — and had scorned the offer. As Edgar Combs put it to me, talking thru the closely woven steel wire mesh that veils the prisoner from his friends in the reception room in Moundsville: “Don tried to make a thug out of me, and he hates me because he couldn’t do it.”

“That was in 1919,” said Combs. “I couldn’t stand the way the miners were treated and I got up and made a speech to a bunch of them. I said they needed a union. It was the year the United Mine Workers was starting into Mingo and things were stirring everywhere. Don Chafin had a big army of thugs on the job all the time. I took my stand anyhow. They didn’t go after me at first. Beat up a man who was with me, but tried another game with me. Moved me into a better house, rent free. Don thought he had bribed me. Had a talk and asked me to be one of his thugs.

“They couldn’t do it, and they began making things hard for me. One Sunday — it was April 1, 1921 — two deputies came to the house with half a gallon of whisky, planted it down and then arrested me for having it and started to beat me with the butts of their guns. I fought back. Got knocked down. One thug was bearing his gun down to shoot me when my wife knocked it out of his hand, and if the crowd hadn’t grabbed her there would have been one less thug.

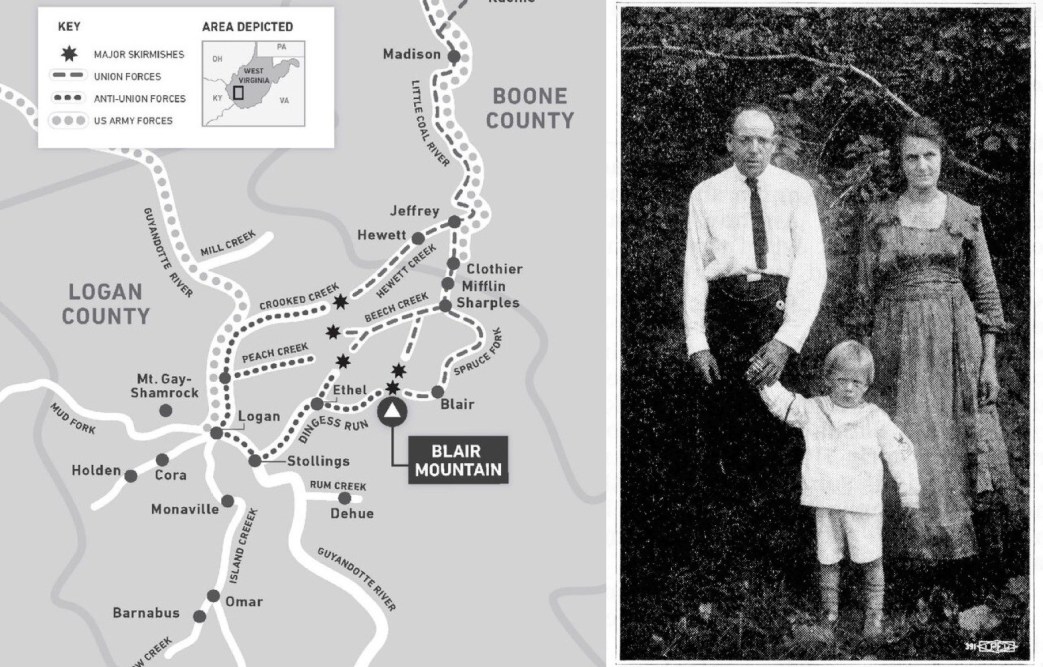

“That’s my Fannie who works in the mill in Moundsville. She has always stood by me.”

I had heard from the miners about Fannie Combs. She is a brave spirit. When Edgar was jailed she moved her six children from the southern end of the state to the penitentiary town in the northern panhandle, to be near her man. But the life is a hard one. There are six children, four girls and two boys. Lillian and Edith, 16 and 15, work and help, but little Edna is less than three and the mother has the household anxieties after her long day in the mill.

Edgar’s voice lost some of its steadiness as he spoke of the folks outside. The boys say he has a most affectionate family life and imprisonment is doubly hard for that reason. The jailer says he sends every cent to his family, including the $5.00 a month the International Labor Defense gives for tobacco and prison comforts. I did not know all this till later, but as he talked on I could feel the affectionate quality of the man. It came with his voice, thru the metal veil that obscured the body. His features were indistinguishable, for the tiny interstices allowed only the general outlines of jaw and skull over the striped suit of penitentiary denim to filter thru.

“I was with the marchers,” he went on; “I never denied it. I did not fire the shot that killed John Gore, but I was in the party up Beech Creek.”

The 813 murder indictments that followed the march were all for the death of this John Gore, who fell in the Beech Creek sector of the fighting. John Gore was one of the chief deputies, Don Chafin’s right hand man. There were a good many other casualties in the 10-mile battle that lasted six days till the federal troops came in time to save the thugs but the coal operators lost no harder- boiled gunman than John Gore. His gat was notched with the lives of workingmen. He was a seasoned instrument of terror and when he passed out abruptly at the age of 45 there were none to regret his loss save his employers.

“Preacher Wilburn led our party up Beech Creek after the thugs started the fighting by shooting up Sharpies,” continued Combs. “Wilburn turned traitor later. He gave state’s evidence for a pardon and promise of $500 and told a lot of lies while he was doing it. We have his signed confession, he made in the penitentiary. It’s in Charleston now. He’s been conducting evangelistic services on Coal River since he got out, they tell me, and working in a nonunion mine. He’s a Baptist. In the old days he was a union man; worked in the week at Blair and preached on Sundays. But that day on Beech Creek he said he’d laid down his Bible and taken his rifle and he didn’t mean to take any prisoners.”

Combs’ name slipped thru the mesh that searched union counties for indictments in the earlier months after the battle. Coal operators, who were then breaking with the United Mine Workers Union, turned over to the Logan authorities, it is said, the list of union men whose dues they had been checking off — and perhaps because Combs had been on Coal River such a short time his name escaped. Anyhow he was not among the first set of three hundred men fetched shackled into Logan courthouse to be arraigned before Don Chafin, with his three heavy guns at the waist; his cousin John, surnamed “Con,” the prosecuting attorney, and their little lickspittle Judge Bland. Combs was not arrested till early 1923. The old man Wilburn and his son John, faced with the need of implicating more men if they were to buy their freedom, named him, among others.

Logan was hungry for a victim. It had, by this time, failed to convict Bill Blizzard, who had gotten a change of venue. The outlook was not too hopeful for getting Frank Keeney. But here was Ed Combs, the fellow who had lived among them and turned against them. They’ll fix him. And they did. He was triumphantly arrested, jailed and held in isolation six months as they worked up their case. No one was allowed to speak to him except his enemies, and his attorney, but the latter even could not confer except in the presence of deputies. Several times a week Sheriff Don Chafin or some of his deputies would walk in, telling him he was sure to hang if he did not squeal. Chafin, a cousin of Don, since killed, used to flourish his revolver in Edgar’s face and threaten to “knock him off,” right there in the cell, a fate that happened to one of the men seized at the outbreak of the march.

One method they used in torturing the prisoner was original. They gave him only boiling water. The single spigot, day and night, ran scalding water only. If the prisoner wanted to drink he draw a cupful and set it. aside till it was tepid enough to drink without injury, and he bathed by sponging from the cup with an end of garment. This from April to November, with nothing to eat but a slim ration of beans, with minute trimmings of butterless bread and sometimes a tiny portion of fat meat. No coffee, tea or fruit.

Time for trial. Word came down he was slated to hang. It was all fixed. The trial was to speed to the framed conclusion — the rope…With this came a promise of freedom if he would betray his comrades. He laughed at them. Then at the last moment came the offer of life imprisonment if he would plead “guilty” personally to having taken part in the particular Beech Creek expedition that fell in with John Gore and his gang. Combs took this alternative. They thought then that he would tell who was with him — and get his freedom. But the miner took responsibility for himself alone and wouldn’t help the state against the rest. In fact he helped to save the rest. At the trial of Frank Keeney in Fayetteville in the following Spring of 1924 Combs came down from Moundsville to swear that Keeney had nothing to do with it. He gave the lie with convincing effect to Preacher Wilburn who was starring for the state. He spoke with the authority of one who had been in the war, and knew the facts about it, and who was not getting paid for his testimony as was Wilburn. And the jury believed him.

Edgar Combs went back to Moundsville to do the rest of his 99 years. But the boys outside were agitating for his release and eventually, a short time ago, his sentence was commuted to 11 years. It is important now to increase this agitation. There is nothing but Logan logic in keeping him inside when the cases against the 813 others have been dropped. And he is needed outside. The open shop, for the time being, has won a complete victory in southern West Virginia. Not only Logan, Mercer, Wyoming, McDowell and Mingo, the traditionally non-union gunman counties are in the enemies’ hands, but Kanawha, Boone and all the others south of the Fairmont region. Every good union man is sorely needed in the fight that is surely coming to win back this territory.

“What do you want the workers to do for you?” I asked him as we parted, thinking he would urge continued effort for his release.

“Send me books,” he said, “books to educate me for the labor movement. I’m going back to it when I come out.”

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1926/v01n04-apr-1926-ORIG-LD.pdf