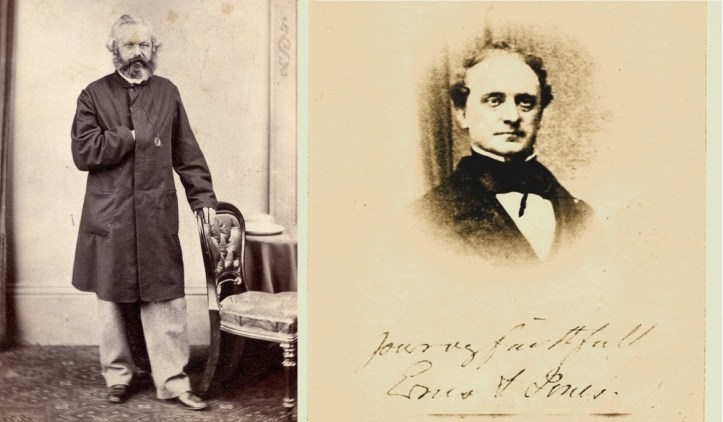

A letter that marks key elements in an extraordinary period of growth for Marx in his early thirties, and the gathering of what the world would know as Marxism. Notably, these ascents occurred during his family’s most desperate personal existence. Exiled from Continental Europe after the Revolutions of 1848 and living as an impoverished refugee in London, Marx immersed himself in the British workers’ movement of the early 1850s. There he started a short, but, for Marx, transformative relationship with the revived Chartists and its leading figures, including the German-born–and speaking (valuable for Marx still learning English)–Ernest Jones after his 1850 release from prison. Marx would help edit Jones’ new People’s Paper, particularly its economic content, beginning his epoch-making study of British conditions which would form the basis of Capital published fifteen years later. Though there were numerous small-scale colonial projects of the German states or companies going far back, the German Empire had yet to exist in 1850, let alone begin overseas colonies, while for Britain, the ‘sun never set’ on that loathsome Empire. A radical Chartist at a time of the Imperial zenith, and the slums of Manchester, Jones made the connection between the Empire and the exploitation and political oppression of the English working class. Jones was arrested in 1848 for calling for support of Ireland’s Young 48ers, and denounced rule in India with poems like “Revolt of Hindostan or the New World,” written while in prison. His passion and perspective would deeply influence Marx, helping to introduce him to an anti-imperialist world view. In this letter written on June 17, 1853 Marx looks behind the figures of British economic reports, connecting them to a wave of strikes in Northern England, includes a full letter from Jones analyzing the situation, and ends his weekly letter with an acrid comment on the current debate in British parliament on the future of India.

‘English Prosperity, Strikes, and India’ by Karl Marx from The New York Daily Tribune. Vol. 13 No. 3809. July 3, 1853.

London, Friday, June 17, 1853.

The declared value of British exports for the month of

April, 1853, amounts to £7,578,910

Against, for April, 1852 5,268,915

For four months ending April 30 [1853] 27,970,633

Against the same months of 1852 21,844,663

Showing an increase, in the former instance, of £2,309,995, or upward of 40 per cent.; and in the latter of £6,125,970, or nearly 28 per cent. Supposing the increase to continue at the same rate, the total exports of Great Britain would amount, at the close of 1853, to more than £100,000,000.

The Times, in communicating these startling items to its readers, indulged in a kind of dithyrambics, concluding with the words: “We are all happy, and all united.” This agreeable discovery had no sooner been trumpeted forth, than an almost general system of strikes burst over the whole surface of England, particularly in the industrial North, giving a strange echo to the song of harmony tuned by The Times. These strikes are the necessary consequence of a comparative decrease in the labor-surplus, coinciding with a general rise in the prices of the first necessaries. 5,000 hands struck at Liverpool, 35,000 at Stockport, and so on, until at length the very police force was seized by the epidemic, and 250 constables at Manchester offered their resignation. On this occasion the middle-class press, for instance The Globe, lost all countenance, and foreswore its usual philanthropic effusions. It calumniated, injured, threatened, and called loudly upon the magistrates for interference, a thing which has actually been done at Liverpool in all cases where the remotest legal pretext could be invoked. These magistrates, when not themselves manufacturers or traders, as is commonly the case in Lancashire and Yorkshire, are at least intimately connected with, and dependent on, the commercial interest. They have permitted manufacturers to escape from the Ten-Hours Act, to evade the Truck Act, and to infringe with impunity all other acts passed expressly against the “unadorned” rapacity of the manufacturer, while they interpret the Combination Act always in the most prejudiced and most unfavorable manner for the workingman. These same “gallant” free-traders, renowned for their indefatigability in denouncing government interference, these apostles of the bourgeois doctrine of laissez-faire, who profess to leave everything and everybody to the struggles of individual interest, are always the first to appeal to the interference of Government as soon as the individual interests of the workingman come into conflict with their own class interests. In such moments of collision they look with open admiration at the Continental States, where despotic governments, though, indeed, not allowing the bourgeoisie to rule, at least prevent the workingmen from resisting. In what manner the revolutionary party propose to make use of the present great conflict between masters and men, I have no better means of explaining than by communicating to you the following letter, addressed to me by Ernest Jones, the Chartist leader, on the eve of his departure for Lancashire, where the campaign is to be opened:

“My Dear Marx:…To-morrow, I start for Blackstone-Edge, where a camp-meeting of the Chartists of Yorkshire and Lancashire is to take place, and I am happy to inform you that the most extensive preparations for the same are making in the North. It is now seven years since a really national gathering took place on that spot sacred to the traditions of the Chartist movement, and the object of the present gathering is as follows: Through the treacheries and divisions of 1848, the disruption of the organization then existing, by the incarceration and banishment of 500 of its leading men—through the thinning of its ranks by emigration—through the deadening of political energy by the influences of brisk trade—the national movement of Chartism had converted itself into isolated action, and the organization dwindled at the very time that social knowledge spread. Meanwhile, a labor movement rose on the ruins of the political one—a labor movement emanating from the first blind gropings of social knowledge. This labor movement showed itself at first in isolated cooperative attempts; then, when these were found to fail, in an energetic action for a ten-hour’s bill, a restriction of the moving power, an abolition of the stoppage system in wages, and a fresh interpretation of the Combination Bill. To these measures, good in themselves, the whole power and attention of the working classes was directed. The failure of the attempts to obtain legislative guaranties for these measures has thrown a more revolutionary tendency in the labor-mind of Britain. The opportunity is thus afforded for rallying the masses around the standard of real Social Reform; for it must be evident to all, that however good the measures above alluded to may be, to meet the passing exigencies of the moment, they offer no guaranties for the future, and embody no fundamental principle of social right. The opportunity thus given for a movement, the power for successfully carrying it out, is also afforded by the circumstances of the present time—the discontent of the people being accompanied by an amount of popular power which the comparative scarcity of workingmen affords in relation to the briskness of trade. Strikes are prevalent everywhere and generally successful. But it is lamentable to behold that the power which might be directed to a fundamental remedy, should be wasted on a temporary palliative. I am, therefore, attempting, in reorganizing with numerous friends, to seize this great opportunity for uniting the scattered ranks of Chartism on the sound principles of social revolution. For this purpose I have succeeded in reorganizing the dormant and extinct localities, and arranging for what I trust will be a general and imposing demonstration throughout England. The new campaign begins by the camp meeting on Blackstone Edge, to be followed by mass meetings in all the manufacturing Counties, while our agents are at work in the agricultural districts, so as to unite the agricultural mind with the rest of the industrial body, a point which has hitherto been neglected in our movement. The first step will be a demand for the Charter, emanating from these mass meetings of the people, and an attempt to press a motion on our corrupt Parliament for the enactment of that measure, expressly and explicitly as the only means for Social Reform—a phase under which it has not yet been presented to the House. If the working classes support this movement, as I anticipate, from their response to my appeal, the result must be important; for, in case of refusal on the part of Parliament, the hollow professions of sham-liberals and philanthropic Tories will be exposed, and their last hold on popular credulity will be destroyed. In case of their consenting to entertain and discuss the motion, a torrent will be loosened which it will not be in the power of temporising expediency to stop. For you must be aware, from your close study of English politics, that there is no longer any pith or any strength in aristocracy or moneyocracy to resist any serious movement of the people. The governing powers consist only of a confused jumble of worn-out factions, that have run together like a ship’s crew that have quarreled among themselves, join all hands at the pump to save the leaky vessel. There is no strength in them, and the throwing of a few drops of bilge water into the democratic ocean will be utterly powerless to allay the raging of its waves. Such, my friend, is the opportunity I now behold—such is the power wherewith I hope to see it used, and such is the first immediate object to which that power shall be directed. On the result of the first demonstration I shall again write to you.

“Yours truly, Ernest Jones.”

That there is no prospect at all of the intended Chartist petition being taken into consideration by Parliament, needs not to be proved by argument. Whatever illusions may have been entertained on this point, they must now vanish before the fact, that Parliament has just rejected, by a majority of 60 votes, the proposition for the ballot introduced by Mr. Berkeley, and advocated by Messrs. Phillimore, Cobden, Bright, Sir Robert Peel, etc. And this is done by the very Parliament which went to the utmost in protesting against the intimidation and bribery employed at its own election, and neglected for months all serious business, for the whim of decimating itself in election inquiries. The only remedy, purity Johnny has yet found out against bribery, intimidation and corrupt practices, has been the disfranchisement, or rather the narrowing of constituencies. And there is no doubt that, if he had succeeded in making the constituencies of the same small size as himself, the Oligarchy would be able to get their votes without the trouble and expense of buying them. Mr. Berkeley’s resolution was rejected by the combined Tories and Whigs, their common interest being at stake: the preservation of their territorial influence over the tenants at will, the petty shopkeepers and other retainers of the land-owner. “Who has to pay his rent, has to pay his vote,” is an old adage of the glorious British Constitution.

***

On the 13th inst. Lord Stanley gave notice to the House of Commons that on the second reading of the India Bill (23d inst.) he would bring in the following resolution:

“That in the opinion of this House further information is necessary to enable Parliament to legislate with advantage for the permanent government of India, and that at this late period of the session, it is inexpedient to proceed into a measure, which, while it disturbs existing arrangements, cannot be regarded as a final settlement.”

But in April, 1854, the Charter of the East India Company will expire, and something accordingly must be done in one way or the other. The Government wanted to legislate permanently; that is, to renew the Charter for twenty years more. The Manchester School wanted to postpone all legislation, by prolonging the Charter at the utmost for one year.—The Government said that permanent legislation was necessary for the “best” of India. The Manchester men replied that it was impossible for want of information. The “best” of India, and the want of information, are alike false pretences. The governing oligarchy desired, before a Reformed House should meet, to secure at the cost of India, their own “best” for twenty years to come. The Manchester men desired no legislation at all in the unreformed Parliament, where their views had no chance of success. Now, the Coalition Cabinet, through Sir Charles Wood, has, in contradiction to its former statements, but in conformity with its habitual system of shifting difficulties, brought in something that looked like legislation; but it dared not, on the other hand, to propose the renewal of the Charter for any definite period, but presented a “settlement,” which it left to Parliament to unsettle whenever that body should determine to do so. If the Ministerial propositions were adopted, the East India Company would obtain no renewal, but only a suspension of life. In all other respects, the Ministerial project but apparently alters the Constitution of the India Government, the only serious novelty to be introduced being the addition of some new Governors, although a long experience has proved that the parts of East India administered by simple Commissioners, go on much better than those blessed with the costly luxury of Governors and Councils. The Whig invention of alleviating exhausted countries by burdening them with new sinecures for the paupers of aristocracy, reminds one of the old Russell administration, when the Whigs were suddenly struck with the state of spiritual destitution, in which the Indians and Mahommedans of the East were living, and determined upon relieving them by the importation of some new Bishops, the Tories, in the plenitude of their power, having never thought more than one to be necessary. That resolution having been agreed upon, Sir John Hobhouse, the then Whig President of the Board of Control, discovered immediately afterwards, that he had a relative admirably suited for a Bishopric, who was forthwith appointed to one of the new sees.

“In cases of this kind,” remarks an English writer, “where the fit is so exact, it is really hardly possible to say, whether the shoe was made for the foot, or the foot for the shoe.” Thus with regard to the Charles Wood’s invention; it would be very difficult to say, whether the new Governors are made for Indian provinces, or Indian provinces for the new Governors.

Be this as it may, the Coalition Cabinet believed it had met all clamors by leaving to Parliament the power of altering its proposed act at all times. Unfortunately in steps Lord Stanley, the Tory, with his resolution which was loudly cheered by the “Radical” Opposition, when it was announced. Lord Stanley’s resolution is nevertheless self-contradictory. On one hand, he rejects the Ministerial proposition, because the House requires more information for permanent legislation. On the other hand, he rejects it, because it is no permanent legislation, but alters existing arrangements, without pretending to finality. The Conservative view is, of course, opposed to the bill, because it involves a change of some kind. The Radical view is opposed to it, because it involves no real change at all. Lord Stanley, in these coalescent times has found a formula in which the opposite views are combined together against the Ministerial view of the subject. The Coalition Ministry affects a virtuous indignation against such tactics, and The Chronicle, its organ, exclaims:

“Viewed as a party-move the proposed motion for delay is in a high degree factious and discreditable…This motion is brought forward solely because some supporters of the Ministry are pledged to separate in this particular question from those with whom they usually act.”

The anxiety of Ministers seems indeed to be serious. The Chronicle of to-day, again recurring to the subject, says:

“The division on Lord Stanley’s motion will probably be decisive of the fate of the India Bill; it is therefore of the utmost importance that those who feel the importance of early legislation, should use every exertion to strengthen the Government.”

On the other hand, we read in The Times of to-day:

“The fate of the Government India Bill has been more respectively delineated…The danger of the Government lies in the entire conforming of Lord Stanley’s objections with the conclusions of public opinion. Every syllable of this amendment tells with deadly effect against the ministry.”

I shall expose in a subsequent letter, the bearing of the Indian Question on the different parties in Great Britain, and the benefit the poor Hindoo may reap from this quarreling of the aristocracy, the moneyocracy and the millocracy about his amelioration.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (for Marx) wrote hundreds of articles in English for the New York Daily Tribune which ran from 1841 and was closely associated with Horace Greeley and, until the founding of the Republican Party, progressive Whigs. Marx contributed from August 1851 to March 1862 as the Tribune’s London correspondent. One of the largest papers in the U.S., Marx’s work was read widely, including by Lincoln who was a subscriber. The Tribune was an important outlet for Marx’s political ideas in the years of European reaction between the failure of ’48 and the International. Marx would break with the paper in 1862 over its increasing conservatism and compromising attitude towards the abolition of slavery during the Civil War. The ten years of political writings for the Tribune in the 1850s, often covering European wars, empires and politics, show Marx’s evolving understanding of imperialism, particularly his work on India and China. We need a Marx-Engels series entirely devoted to collecting and annotating their entire Daily Tribune articles. Until then, we will post compelling ones here.

Access to PDF of original issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030213/1853-07-01/ed-1/seq-5/