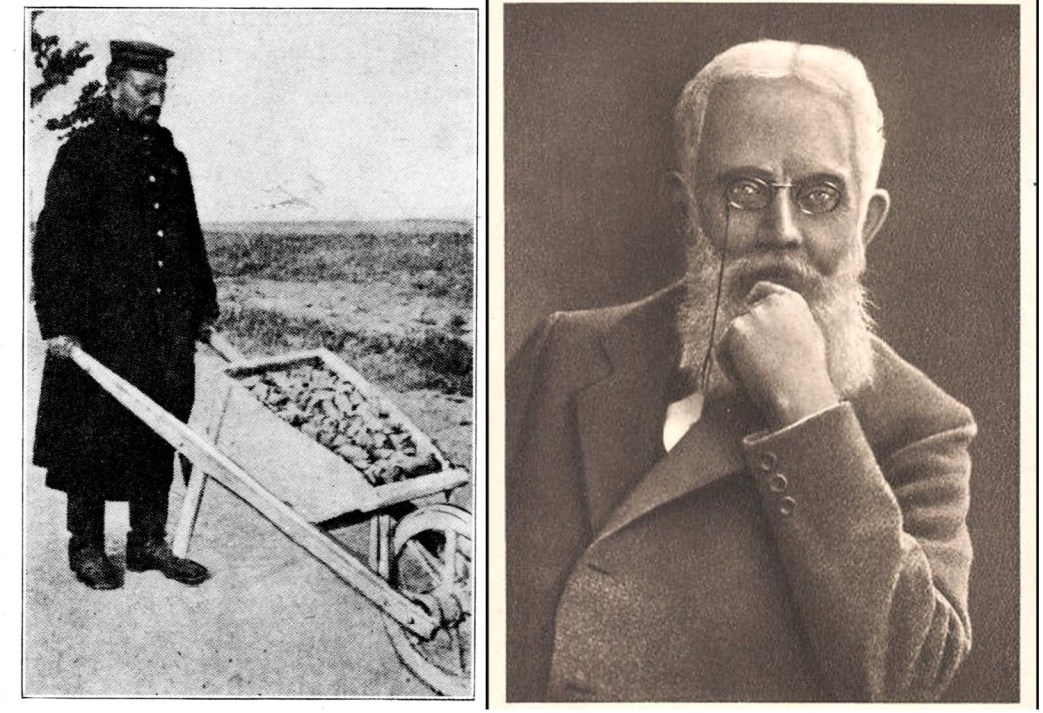

Wonderful words by Mehring as he remembers checking the ardor of a young Karl Liebkencht, now 45 and of great moral stature, serving time in prison for his treasonous May Day call to end the war and the German Empire.

‘Karl Liebknecht’ by Franz Mehring from Young Socialists Magazine. Vol. 11 No. 4. April, 1917.

Stone wall do not a prison make

Nor iron bars a cage:

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for a hermitage.

Lovelace the poet who wrote these words, lived in the middle of the seventeenth century. He was a staunch defender of royalty, a cavalier of Charles I of England, whom he followed into prison, when Cromwell won his victory. It was against Cromwell, his jailor, that these lines were written.

The beauty and truth of these lines so charmed the German Herder that he included their translation in his folk songs, with the Erlkönig and the Heideröschen.

On a cell door of an old prison in Berlin, that has since been torn down, the same thoughts were carved by one of the victims of the reactionary rulers of the past century.

Its words gave courage to youths like Arnold Ruge and Fritz Reuter. And later Freiligrath burst open the doors that held Hübner, the rebel of 1848, with the words of the 17th century royalist on his lips.

And these words again came to my mind, when on the 28th of June, returning to my home, I found on my desk, in a boys unformed handwriting a slip of paper with the words: “My father was condemned to 2 1⁄2 years imprisonment today on the charge of treason.” So the shadow of treason has fallen on the third Liebknecht generation. Karl Liebknecht felt its force much earlier than his eldest son. His mother bore him beneath her heart when his father, in the excitement of war-time, amid a storm of the wildest and most impossible accusations, was held for one hundred days pending investigation on charges that meant the worst. The sufferings that racked the soul of this brave woman in those awful months, she often said, have left an indelible imprint on Karl’s inmost nature.

I have known him for almost a generation. He was a youngster, 17 or 18 years of age, when he wrote me a letter from Leipzig asking me for a copy of the Berlin Volkszeitung, for the use of some students’ organization that he had founded. This was in the time of the Socialist exception laws, when the Berlin Volkszeitung was by far the most radical paper in existence in Germany. I responded gladly to his request, for at that time we, in Germany were not yet so self-sufficient in our wisdom as we are today. We still remembered that Schiller had written his “Robbers” when he was but 19 years of age, and we yet felt that the lovable foolishness of youth is often worth more than the fearsome wisdom of a lame old age.

Several years later, when his parents moved to Berlin after the exception laws had fallen, I met Karl Liebknecht personally for the first time. At that time he was a student, barely twenty years of age, gifted, industrious, brilliant, bold, a little too cock-sure perhaps, as every real youngster should be. But he was never arrogant, never vain, and above all, never hurt when one refused to accept unconditionally his first budding shots of wisdom. Karl Liebknecht had inherited the lovable modesty of his parents.

Later he and I often fought serious battles, although our personal friendship never suffered even under the severest strain. When I conducted the Leipziger Volkszeitung, I often found it necessary to check the enthusiasm of the fiery youth, especially in those days when he conducted the valiant fight for the young people’s movement. He was always a little indignant when he came to Leipzig with his pockets full of burning essays to find the “old man” unexpectedly at his desk. Nothing could arouse him to such furious resentment as to have me refuse some particularly incendiary article of his “for the sake of your wife and your mother,” who both belonged to my dearest friends. For Karl Liebknecht, the real son of his father, has never known personal considerations in his fight for our great cause.

Today I remember my victories over Karl with slender satisfaction. They were so easily won, for after all, they rested upon the power that my control of the printing-presses of the Leipziger Volkszeitung gave me. How fallacial is the much-vaunted wisdom of age! Would the sparks that I so virtuously stamped out at that time, perhaps have kindled a cleansing flame? Today, I do not know. But I do know that the wisdom of forty years in the press and penal laws of Germany failed my young friend after all, when it should have helped him most. Together Karl Liebknecht and I laid the treasonable document that cost him a year and a half in military prison before our friend Teyffert and I approved of its publication. Later, when we fought with equal weapons, I never succeeded in throwing water into the fermenting wine of Liebknecht’s enthusiasm. Today this fact brings to me a melancholy satisfaction.

Young Socialist’s Magazine was the journal of the original Young People’s Socialist League and grew of of the Socialist Sunday School Movement, with its audience being children rather than the ‘young adults’ of later Socialist youth groups. Beginning in 1908 as The Little Socialist Magazine. In 1911 it changed to The Young Socialists’ Magazine and its audience skewed older. By the time of the entry into World War One, the Y.P.S.L.’s, then led by future Communists like Oliver Carlson and Martin Abern, had a strong Left Wing, creating a fractious internal life and infrequent publication, ceasing entirely in 1920.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/youngsocialist/v11n04-apr-1917_Young%20Socialists.pdf