Wolfe provides a useful background on the beginnings if U.S. imperial dominance of South America after World War One with a look at investments in, and political intrigue for control of, the Bolivia/Chile/Peru border region.

‘The United States and Tacna Arica’ by Ella Wolfe from The Communist. Vol. 6 No. 2. April, 1927.

AMERICAN imperialism sails under the flag of the Monroe Doctrine into the most remote provinces of South America. Urged on by American interests it participates in all of Latin America’s quarrels. No political or economic problem in the Western hemisphere is too trivial for the U.S. to attempt to settle. No important problem can be settled without the United States. The white man’s burden of American imperialism fights popular uprisings in Latin America; foments revolutions regularly; engages in price-fixing; establishes systems of currency; controls customs; and regulates boundary disputes.

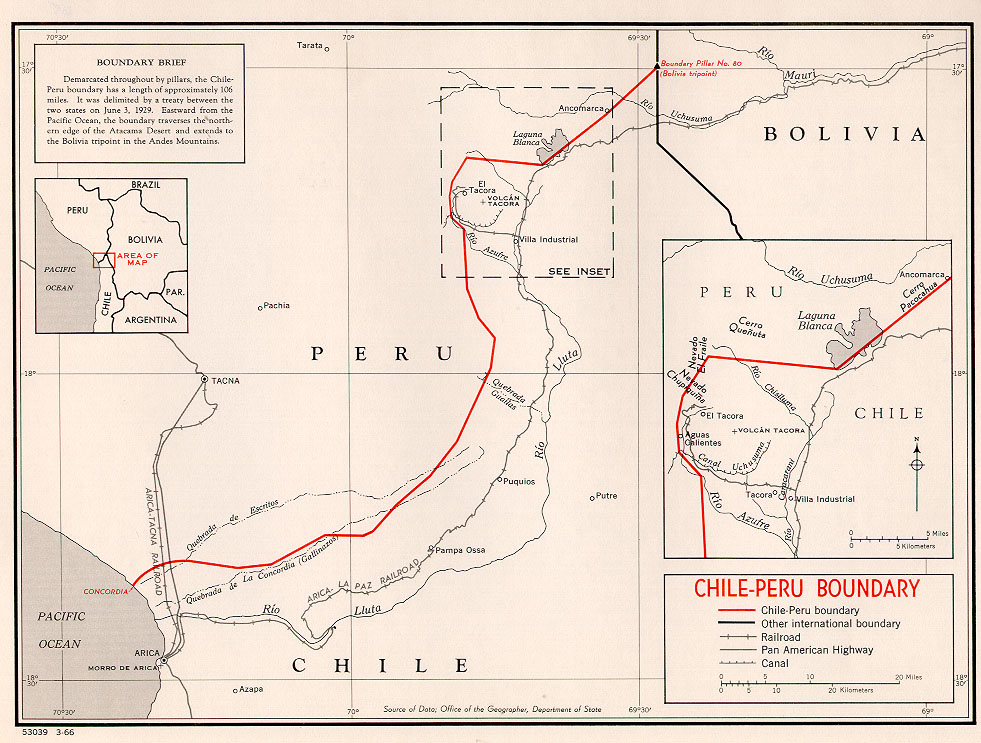

For the past four or five years the agenda of the U.S. State Department has included the long standing quarrel between Chile and Peru over TACNA ARICA. What are these provinces of Tacna and Arica and why are We so busy trying to patch up the quarrel?

Way back in 1873 Peru and Bolivia entered into a treaty of alliance against the aggressive policy of Chile. Peru had accused Chile of seeking a pretext for war in order to secure the rich nitrate deposits of Bolivia and Peru. Chile denounced Peru for intriguing with Bolivia against her interests. When six years later Bolivia imposed an export tax on the products of a Chilean mining company, Chile sent her battleships to seize Antofogasta, Bolivia’s only and most important port. Bolivia then declared war on Chile, and a month later Chile declared war on Peru.

After a bitter three year war Chile, due to her superior military and naval forces, better organization of her government, and the greater unity if her people, came out victorious. The war terminated with the Treaty of Ancon (1883) which provided:

1—Peru, to cede unconditionally, to Chile the province of Tarapaca.

2—To grant to Chile, for a period of ten years, the provinces of TACNA ARICA (containing the richest nitrate deposits in the western hemisphere).

3—At the end of the ten-year period a plebiscite to determine to which of the two countries the provinces of TACNA ARICA were to belong permanently.

Bolivia was forced to give up the province of Antofogasta to Chile, thus losing her outlet to the Pacific.

Because almost half of the revenues of the Chilean government come from the export tax on nitrates produced in TACNA ARICA—Chile has repeatedly refused to carry out the plebiscitary provision in the treaty of Ancon. The result has been continues friction and threats of war between Chile and Peru.

Several attempts at arbitration failed; a move to have the dispute settled by the League of Nations was frustrated by former Secretary of State Hughes, who invoked the Monroe Doctrine. Finally it was decided by President Coolidge to hold the plebiscite. This decision was considered a distinct victory for Chile,—because Chile had had over 45 years in which to Chileanize thoroughly the two districts; first by expelling Peruvian teachers and priests, and by drafting the Peruvian youth into the Chilean army, and in general carrying on a systematic policy of colonization.

Coolidge decided that the plebiscite was to be supervised by a commission consisting of one representative from Chile, one from Peru and an American chairman. The expenses of the plebiscite to be paid by each country, in equal shares, irrespective of the results. And the country receiving the award of the plebiscite was to pay to the other $5,000,000.

The preparations for the plebiscite aroused great bitterness in Chile and Peru. The nationalists of both countries began to adopt extreme measures to insure the victory for their country.

President Coolidge appointed General Pershing to head the Plebiscitary Commission. This appointment was accepted by both countries. When Pershing arrived in Chile he found that the commission was being delayed by alleged violence against Peruvian voters. When Pershing protested against these methods of the Chileans he was attacked by the whole Chilean press and became so unpopular that finally he had to be recalled.

Then Coolidge sent General Lassiter, who after a short while was also recalled and the United States admitted that her attempt to hold a plebiscite was a complete failure.

In an effort to avoid the damage to the prestige of the U.S. for the failure to carry out the plebiscite, Coolidge proposed direct diplomatic settlement, at a conference which was called in Washington. This conference was attended by a representative from Chile, and one from Peru. Secretary of State Kellogg acting as chairman. The American government suggested at this conference that the plebiscite be suspended. Peru accepted the proposition but Chile refused, and the conference terminated unsatisfactorily.

Before summing up the provision of the latest proposal of Secretary Kellogg to Chile and Peru concerning the provinces of TACNA ARICA, let us see why American interests are so much concerned with a policy of peace in the three countries involved—Chile, Bolivia and Peru.

Prior to the war American investments in South America held third or fourth place, but since the war they have jumped to second and in a number of countries hold first place:

BOLIVIA—Since the war American interests have invested heavily in tin mining and in the development of oil resources. In 1912 U.S. interests in Bolivia were estimated at 10 million dollars. In 1920 the U.S. held third place with an investment of 15 millions, France coming first with 20 to 25 millions, and Great Britain second with 17% millions. Today the U.S. investments are over 80 million dollars of which over 50 millions are invested in tin.

The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey has a 7,400,000 acre concession of oil lands in Bolivia for 55 years. This concession includes not only the right to extract oil but the right to operate railways, harbors, telephone and telegraph, and other public utilities.

The National Lead Company of the U.S. has acquired for 30 million dollars huge tin properties, including mines and railways. This new company will control 80 per cent of the tin production of Bolivia. The Guggenheim interests own many of the largest tin mines.

American interests have also secured the concession of building a railway that will connect Bolivia with Northern Argentina.

CHILE—In 1912 the United States had only 15 million dollars invested in Chile. But by 1920 six American companies had invested 119 millions in copper, iron and nitrate mines. Today the total investments of American interests in Chile are estimated at over 400 millions. The chief American investments in Chile are in copper, iron and nitrates.

Copper. The United States ambassador in Chile reporting for an average week in copper production, states that out of 177,000 tons produced 157,000 tons belonged to American investors. Anaconda Copper Co. (Guggenheim) controls the largest copper mines in Chile which are the largest copper mines in the world.

Iron. The Bethlehem Steel Co. has over 15 million dollars invested in the Chile Iron Mines Company which is equipped to produce 1 million tons of iron annually.

Nitrates. American interests are rapidly absorbing this field. W.R. Grace & Co. has a controlling interest in 3 nitrate properties. The Guggenheim interests have bought out the Anglo-Chilean Nitrate Co., which owns the largest nitrate mines in Chile.

PERU. In 1918 American investments in Peru were 50 million dollars. By 1920 the figure jumped to 90 millions, and by 1925 to 100 millions, with Great Britain still in the lead with interests estimated at 125 millions.

The heaviest American interests in Peru are in copper mining. The American Smelting & Refining Co. and Anaconda own some of the largest gold, silver and copper mines of Peru. The Vanadium Corporation of America controls six properties in Peru containing the largest vanadium deposits in the world and producing 92 per cent of the world’s total.

The Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey has over 100,000 acres of oil lands, controls over 70 per cent of Peru’s production of petroleum and over 90 per cent of the petroleum exports. Great Britain produces only 23 per cent of the petroleum.

(All figures taken from Robert W. Dunn’s “American Foreign Investments”.)

It is manifestly to the interest of the colossal and ever-growing investments of the U.S. in the countries of Western South America that the mutual conflicts among these countries themselves be reduced to a minimum. With American investors, sometimes the very same investors in each of the countries involved, this is obviously desirable. But then there are so many conflicting circumstances

The country that is awarded the rich province of Tacna through American influence will be kindly disposed to new requests on the part of American concession seekers. Who, then will get the award?

A few months after the failure of the Washington conference, Secretary Kellogg sent another note to Chile and Peru, in which he suggested that the controversy of TACNA ARICA might be solved by giving the entire disputed territory to Bolivia, in return for payment by Bolivia to both Chile and Peru. The note further provided that the entire district of Arica leading from the Pacific to the interior of Bolivia should be demilitarized. He excluded from this provision the fortress of Morro, which commands the port of Arica, and proposed that the fortress be turned into a “lighthouse” under the control of an “international commission.”

This note provides neither a practical nor an immediate solution. The aim of it is to mark time. Bolivia accepted the proposal with joy. Chile accepted it “in principle,” which means that she will be ready to turn over the provinces to Bolivia after she has extracted all the valuable nitrates. Peru, in her note to Kellogg on January 12, 1927, has categorically rejected his latest proposal telling him that she is not disposed to give away at any price what is rightfully hers.

The provision of the latest Kellogg note that has met the severest criticism in the Latin-American press, is the one referring to the fortress of Morro to be made into a lighthouse under the control of an “international commission.” It was pointed out that Morro fortress would be another point of defense for the United States—her “Gibraltar of the Pacific.”

The provision of giving Tacna Arica to Bolivia has been explained by the eagerness of American interests to get complete control of Bolivia’s tin mines. Tin is an extremely essential raw material for American industry. The United States consumes 60 per cent of the world’s tin output, but is still to a great extent dependent upon foreign sources of supply, in great part British. About 40 per cent of the world’s tin is mined in Bolivia, still to a great extent controlled by British capital. Kellogg’s proposal, therefore, will help American investors secure still more favorable terms in Bolivia.

Chile is not offended by the proposal. After all, the provinces never belonged to her. She feels rather glad that Kellogg did not propose the return of TACNA to Peru because Peru might be more insistent on an early carrying out of such a treaty, but Bolivia is much weaker. At any rate it is easier to make Bolivia see reason, and she can be convinced to wait for TACNA until Chile has exhausted the nitrates therefrom. How can Bolivia refuse to await, when it is her own American friends that are extracting the nitrates in Chile?

Peru’s national pride has been wounded. But what is national pride between friends? With such staunch advisers as Standard Oil and Anaconda—who know how to subsidize the officials and the press—Peru will yet be convinced that what Kellogg proposed will redund to the peace of Latin America and to the prosperity of American finance.

Peru’s unconditional rejection of Kellogg’s last note will rest the Tacna Arica controversy for a long time. The universal hostility toward the recent American policy in Mexico and Nicaragua suggests that Chile and Peru may yet turn to a Latin-American tribunal to decide their problem. In fact, a movement has been started in Chile to organize some judicial body with power to pass upon Latin-American controversies. Many of the intellectuals in the Latin labor movement and some of the trade unions are consciously striving to establish some kind of Latin-American bloc to fight the steady encroachments of the Monroe Doctrine.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This The Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v06n02-apr-1927-communist.pdf