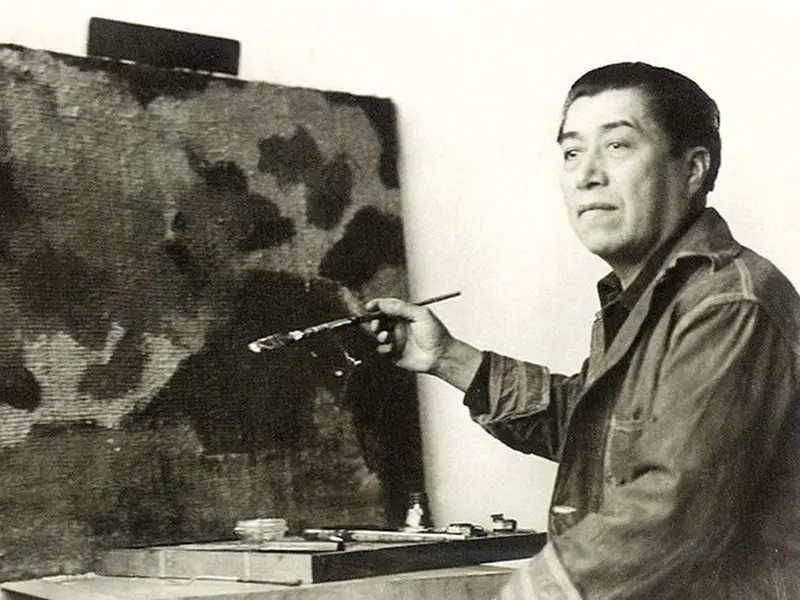

Xavier Guerrero plants his flag, declaring the revolutionary purpose to his art. Translated by his comrade Tina Modotti.

‘A Mexican Painter’ by Xavier Guerrero from New Masses. Vol. 3 No. 1. May, 1927.

Translated by Tina Modotti

Ca’canny, opportunist and fake revolutionary art, convertible into a cheque to bearer, has nothing to do with art involved in the class.

The plastic arts, as the noblest manifestation of man and as an intense means of expression, must be put to the service of world revolution.

The undeniable advance towards social transformation in the present century in the most developed parts of the world demands clearly of the directors of the culture of our time a system of responsible social ethics. They owe it to the youth of today to seek out and tell the truth about the bases of our social structure.

The lack of vision of those who control education, and what is worse, their deliberate “intellectual” manoeuvring to hold back advanced study, have already borne fruit in the confusion and lack of direction of the main part of the youth of the world. The future advance of society will be wrecked if responsible leaders fail to throw light on the mainsprings of human activities. Men and women, awake to their age, must set to work. Let us explain the economic bases of the world to the four winds, hold up into the light the roots of the class war between exploiting and exploited. Then and only then will we have proved that plastic art really exists as one of the important currents of human life.

Organization of the producing class against the dominant class invariably produces conflict. Out of this struggle come more or less intense rhythms of emotion, tracing out the curves of the beauty implicit in the ardor and joy of the fight, the natural results of the tussle with a mighty economic problem. Thus plastic art becomes divided into two opposed factions, passive art and active art; bourgeois art, convertible into expensive bric a brac, and proletarian art as a collectivist international doctrine.

Slave-owning society had its own aesthetic and plastic expressions; so did feudalism; the Renaissance remade art to suit its needs. Whether we like it or not, social-political-economic conditions have their way with the multiform activities of man’s life. From the expression of the enslaved to the expensive fittings of aristocratic-bourgeois society, every human gesture must change in an age when an electric current applied to a particle of radium on a hill will light up a whole city. How much more will they change when the worn out social moulds crumble away, leaving one single class?

If we are strong we must be cogs in the advancing social machine.

Into this vast prospect art goes forward in its social function. In Mexico, four centuries ago, the whites arrived, clothed in iron and ambition, and took from us, among other things, our cosmic paganism. Our ancient culture caved in with the disappearance of our writers, geometricians, astrologers, painters and sculptors. The conquerors gave us phonetic writing instead of picturewriting. But still under all the oligarchies, wars, and political squabbles, the power to produce art has survived among our people. We still can express the passion for beauty and rebellion; and now with a new courage that is a scorn of etiquette and of the wasted dynasties of politics and taste, we are ready to give expressive form to the class struggle.

Art today must be impersonal, a weapon fashioned and wielded by the international proletariat. It must formulate the demands of the masses. In Mexico today we can’t write on the cliffs with obsidian knives nor can we carve out of basalt, but we can, after four centuries of very gradual transformation, open the throttle and drive ahead into the first rank of world events.

Instead of romantic consumptive art, steeped in the theatricalism of the intellectuals, let’s have an art that is a simple day’s work in defence of the exploited. The needs of the great collective masses will dictate the forms of a simple art modelled out of the harsh stuff of life.

This is the great task.

The ocean is stormy and full of reefs. The old diploma-ed artists are raising their voices in lamentation.

But the youth of the twentieth century will pay no attention to dotards. We will paint in the street, we will design revolutionary posters, paint signs on stores for the sake of leaving in the corner the symbol of the hammer and sickle or a single phrase of propaganda. Don’t the oil companies proclaim their commercial strength in thousands of bright painted service stations? We will put up walls at crossroads to describe in painted tiles the misery of our country people, starving in a land of abundance. Don’t they put up crosses and niches for saints at the same crossroads to proclaim the fanatical fetichism of the church? The villages in Mexico have their own painters; with them we will paint in fresco the struggles of workmen and peasants, so that the adobe walls of the smallest hamlets shall tell stories to the country people and the children. We will put up playgrounds and bathhouses; on their walls in clear colors we will paint simple instruction in hygiene. Since our governments have not taught the people to read type, we will give them plain visual forms to read.

Our function is to paint in union halls, in cooperatives, in workers’ meeting places, always leaving the stamp of the class struggle on our work. We will fight too, to spread the proletarian press until it reaches the most inaccessible crannies of the hills, always interpreting the feelings and the daily fight of the masses until at last we shall have built an economic, political and military structure of our own that will be the scaffolding of an international proletarian art and of the classless culture of the future.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1927/v03n01-may-1927-New-Masses.pdf