A turning point in 1920s Europe was the June 9, 1923 overthrow of Agrarian Party leader Aleksandar Stamboliyski by the Bulgarian military, instituting a reign of terror under the White Guard rule of Aleksandar Tsankov. At the time the Bulgarian C.P. was one of the most influential in the world, a genuine mass party it was the largest single Party in Bulgaria and failed to intervene in the coup. Repression was met with lost armed risings, followed by guerilla operations, and then terrorism with the Bulgarian C.P., as it was, destroyed in prison, exile, and the grave over the next years. A generation of revolutionaries wiped out.

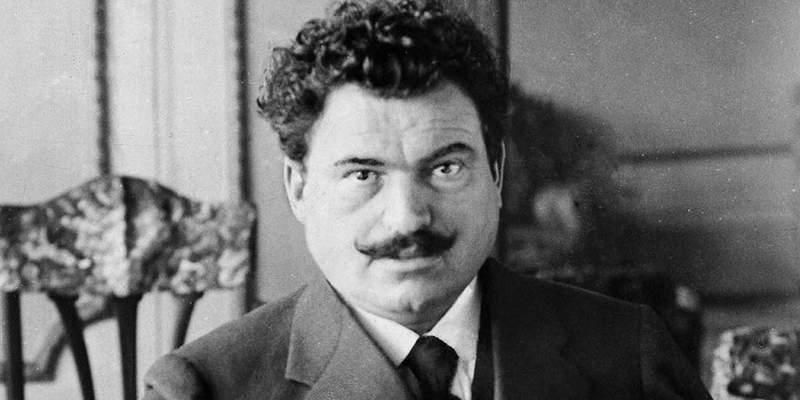

‘The History of the Bloody Terror in Bulgaria’ by G. Dimitrov from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 No. 52. June 25, 1925.

The Bulgarian terror is by no means an ordinary occurrence. Although it reflects the general offensive of bourgeois reaction in the whole capitalistic world, this terror differs essentially, both in its character and its methods from the terror in Roumania and Jugoslavia, in Italy and Spain, in Poland, Hungary and Esthonia and in all other countries.

The essential feature of the terror in Bulgaria is the systematic, organised, physical extermination of the advance-guard of the working class and of the mass of peasants. For the first time in the new political history of peoples, the bourgeoisie, as the ruling class, has shown itself not content merely to rob the mass of the people of their elementary rights and liberties, but is seeking to annihilate the revolutionary workers’ and peasants’ movement by the wholesale extermination of the most awakened and leading sections of the working masses, making use for this infernal purpose of the State apparatus which is in its hands.

How can these peculiarities of the Bulgarian terror be explained?

We must first of all take into consideration that the most important and the leading strata of the Bulgarian bourgeoisie, which do not include as much as 5% of the whole population of the country, have arisen from the ranks of the old usurers and traders who, during the Turkish rule, were agents and middlemen of the Turkish authorities for the exploitation and suppression of the Bulgarian working population. This stratum of the bourgeoisie was saturated to the bone with the shameless Jesuitism and Turkish barbarism which prevailed in the old Turkish empire.

The bourgeoisie maintained an aloof and treacherous attitude towards the revolutionary movement against the Turkish regime, a movement which was guided by the national intelligenzia and supported by the peasants and manual workers. Botew and Lewski were, for instance, victims of the treachery of the Bulgarian “Tschorbadshi” (the rich), the lackeys of the Sultan and of the Turkish Pashas.

The Bulgarian bourgeoisie received the power and its position of supremacy simply as a gift from the hands of Czarist Russia after the Russo-Turkish war of 1877. It never conducted a revolutionary campaign and has no revolutionary traditions. The chief sources of its increase of wealth were the heavy taxation of the mass of the people, trade and speculation in agricultural products, Government loans and the profits they made as commission for their services in helping to subjugate Bulgaria to the Great Powers in connection with the latter’s imperialistic ambitions in the Balkans.

During the 25 years’ rule of the Czar Ferdinand, that crowned agent of German and Austrian imperialism, the Bulgarian bourgeoisie, arch-thief that it is and incapable of independent industrial activity, lusted after rich territories in the Balkans after Macedonia and Thrace, and dreamed of establishing its supremacy in the Balkans.

It was just in the service of the policy of conquest that the Bulgarian bourgeoisie, under Ferdinand’s lead, established an intolerable militarism in the country and prepared on all sides for war against Turkey, in whose hands the territories in question were at the time.

And in 1912, as is well known, they, in alliance with Serbia and Greece and under the protection of Czarist Russia, declared a Balkan war against Turkey. The Turkish army, towards which the local population was hostile, was quickly beaten. Macedonia and Thrace were evacuated by the Turkish armies. Bulgarian troops reached Chatalja, close to the gates of Constantinople itself.

Two years later however (September 1915) Bulgaria was again drawn into the European war, on the side of the Central Powers. The rapid annihilation of Serbia and the occupation of Macedonia as far as Salonika once more turned the heads of Ferdinand and the rapacious Bulgarian bourgeoisie.

Discontent with the prolongation of the war became very widespread throughout the country. It even extended to the army at the front, and was intensified there owing to the brutal treatment of the soldiers and the frequent executions. On September 10th 1918, Bulgarian troops mutinied at Dobropolje, abandoned the trenches, and marched with their weapons in their hands to Sofia, to settle accounts with those responsible for the war. Thanks to the German artillery in Bulgaria, the revolting Bulgarian troops, marching on Sofia, were beaten. That time the bourgeoisie succeeded in retaining the power in its own hands. It was only compelled to sacrifice its Czar Ferdinand, who was forced to abdicate in favour of his son Boris and to flee the country.

For the second time the nationalistic policy of conquest of the Bulgarian bourgeoisie had met with a complete reverse. Bulgaria, instead of annexing Macedonia, Thrace and even Albania, received the treaty of Neuilly. The districts of Zaribrod and Bossilegrad were taken from it, its standing army was abolished, the number of its fighting force limited and the payment of heavy reparations was demanded.

The bourgeoisie, which held the people and its mass parties–the Agrarian League and the Communist party–responsible for the bankruptcy of its adventurous policy, foamed with unbounded rage and lust for revenge on the Bulgarian workers and peasants. But at that moment when, after the victory of the Russian revolution, when the wave of revolution was rising throughout Europe and in the Balkans, and when the Bulgarian people was peremptorily demanding reparation for the horrors and distress it had experienced during the war, it was obviously impossible to give vent to this rage and thirst for revenge on the part of the bourgeoisie. On the contrary, it felt obliged to make some temporary concessions to the tortured mass of the people in order to maintain its class-supremacy in the storms which had arisen.

So the Bulgarian bourgeoisie, with clenched fist and gnashing of teeth, reconciled itself with the assumption of power by Stambolisky’s peasant government at the end of 1919, hoping that it, as had the social democrats in Germany and other countries, would rescue the bourgeoisie from the danger of revolution, and that the bourgeoisie would then manage to take the power once more into its own hands and to revenge itself to the full on the people.

In spite of its half-hearted and inconsistent policy. Stambolisky’s peasant government attacked the vital interests of the bourgeoisie in a way that made itself felt. It followed, though with vacillating footsteps, the path of transferring the burden of the serious consequences of the war, the economic destruction and the crisis, mainly on to the shoulders of the bourgeoisie. It imposed taxes on war profits, on the profits of limited companies and on unearned income. It introduced the grain monopoly, thus depriving speculation capital of its previous enormous profits. It restricted the possibility of speculation capital making use of the credit of the State. A law as to the expropriation of houses for public purposes was passed; a threat to house-property owners. A law as to the ownership of land by the workers was passed; a menace to large property owners.

At the parliamentary elections on March 28th 1920, the whole of the bourgeois parties and the social democratic party together had 300,000 votes out of 1 million votes cast in the whole country, but on April 22nd 1923 they polled only 272,000 votes, whereas the Agrarian League increased its vote from 347,000 to 557,000 and the Communist party from 182,000 to 220,000. Whilst the votes of the bourgeois parties and the social democrats fell from 38% to 26%, the votes of the agrarians and communists together increased from 62% to 74%.

The exasperation of the bourgeoisie reached its utmost limits. Their first revenge exceeded all bounds. Having lost all hope of recapturing power by legal means, by way of elections, they concentrated their whole attention and all their efforts on preparing conditions in which they could, by force and by unparliamentary methods, liberate themselves from the peasant government and from the organised movement of the masses of workers and peasants in the country.

With this object in view they mobilised, with the support of the Court, the ex-officers of the army and the mass of officers who had been placed on the retired-list because of the reduction of the army. They also made use of the 10,000 Russians of Wrangel’s army who were in the country. They won over to their side the armed Macedonian organisation. They made sure of the support of England and Italy who were highly dissatisfied with Stambolisky’s policy, because of the advances he made to Yugoslavia, France’s agent in the Balkans. England, who needed the Balkans in order to strengthen its influence in Asia Minor and to form a solid base for its campaign against the Soviet Union, regarded the Stambolisky Government and the mass communist party in Bulgaria as a serious obstacle, and willingly gave support to the conspiracies of the Bulgarian bourgeoisie.

Having thus laid its plans, both internal and external, the Bulgarian bourgeoisie watched for the moment for decisive action. The subsidence of the wave of revolution in Europe helped in the realisation of its aim. The immediate danger of the proletarian revolution had passed. The policy of the Stambolisky government, which was hostile to the workers and which was doing more and more to encourage dissension between the working class and the mass of the peasants, also helped the Bulgarian bourgeoisie.

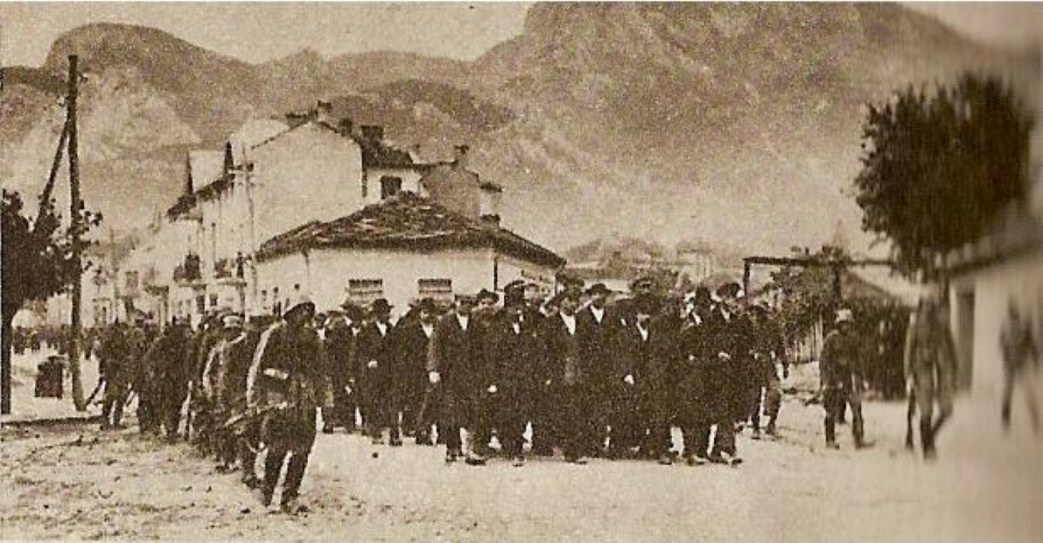

And, on June the 9th 1923, the crew of grasping bankers and speculators, generals who had come to grief in the war and professors who coveted an easy political career, all of whom relied on the support of the plotting military league “Kubrat“, overthrew Stambolisky’s parliamentary peasant government by means of a military revolt, with the help of Wrangel’s followers who were at the time in Bulgaria and of the Macedonian organisation. They seized the power in one night by sheer methods of violence, killed a number of the peasant ministers, deputies and other distinguished politicians, filled the prisons with thousands of peasants and workers who had opposed the overthrow of the government, and subjected the Bulgarian people to a military dictatorship.

The peasant government was replaced by the Zankov Government which was formed on the spot from all the bourgeois parties, including even the social democrats, who amongst them all had only 30 deputies in a Parliament consisting of 245. The enormous majority of the Bulgarian people was decidedly opposed to the late government’s overthrow and showed open hostility to the government imposed upon them. The fatal mistake of the communist party in remaining passive during the overthrow of the government, directly contributed to the bourgeois success. The gang of bankers, generals and professors who were of the opinion that the Agrarian League, having been deprived of their leaders during the putsch, the mass organisation of the Bulgarian peasants was already destroyed, proceeded with the preparations necessary for the destruction of the Labour movement, of the communist party which numbered 40,000 members and 220,000 voters, of the trade unions with 35,000 organised workers of both sexes, of the workers’ co-operative association “Osvobosdenij” with 70,000 members, of the organisations of women and juveniles and of the wide-spread Labour Press which had a larger circulation than that of all the bourgeois and social democratic newspapers put together.

And indeed, two months after the June revolution, on September 12th 1923, the Zankov Government arrested more than 2000 functionaries of the Labour movement (deputies, municipal and district councillors, mayors of villages, journalists, party and trade union secretaries etc.) on the pretext that the workers and peasants were preparing an armed insurrection in order to establish the Soviet power in Bulgaria. They closed the workers’ clubs and turned them into police stations, confiscated the property, the printing works, the private capital and the archives: of the party and trade union organisations, prohibited their newspapers and every other activity and at the same time proceeded with a wholesale persecution of thousands of members and partisans of the Labour movement.

In this way the Zankov Government, in 1923, provoked the September insurrection of the Bulgarian workers and peasants who rose to protect their rights and liberties of which they had been robbed without any ceremony, and to protect their lawful existence.

Having succeeded in suppressing the popular rising with the help of Wrangel’s followers and of the armed sections of the Macedonian organisation, the Zankov Government murdered some thousands of the prominent workers, peasants and intellectuals who were under arrest (the greater part of whom ha been imprisoned during the insurrection), and drove thousands of others out of the country.

In spite of all this however the Government did not succeed in restoring peace in the country and ensuring a tranquil rule. On the contrary, the September massacre only served to increase the discontent and irritation of the people against the regime of terror. The mass of peasants and workers who, by bitter experience, had thoroughly learned that the cause of their defeat lay in their lack of unity, continued with united forces the fight against their executioners and for the recapturing of the rights and liberties of which they had been robbed.

The Zankov Government replied to this justifiable self- defensive fight, in the course of twenty months, by indescribable deeds of violence and cruelty, by an uninterrupted series of political murders and the most insolent provocations. The bourgeoisie once more, in an elementary form, wreaked its revenge on the working class and on the peasant masses in connection with the explosion in Sofia, which, by means of forged documents, they represented as being the beginning of an armed insurrection. On this occasion another 2000 leaders of the workers and peasants were slain, more than 10,000 workers and peasants arrested and handed over to the court martial, and they even went so far as to revive the mediaeval gallows in the city square of Sofia.

By all these atrocities and by their deeds of cruelty, revenge and frenzy, the Bulgarian bourgeoisie, is however, simply proving its unfitness to continue to rule the country and to guide the economic and social development of the Bulgarian people. In shedding the blood of the best of the working masses, in increasing the anarchy and uncertainty in the country to the utmost and inevitably rousing the opposition of every honest element in the country, the Bulgarian bourgeoisie is zealously digging the grave of its own supremacy.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n52-jun-25-1925-inprecor.pdf