Louis C. Fraina was a keen observer and incisive chronicler of the German Revolution, here giving an analysis of National Congress of Workers Councils held in Berlin on December 16, 1918.

‘End–And Beginning’ by Louis C. Fraina from The Revolutionary Age. Vol. 1 No. 11. December 28, 1918.

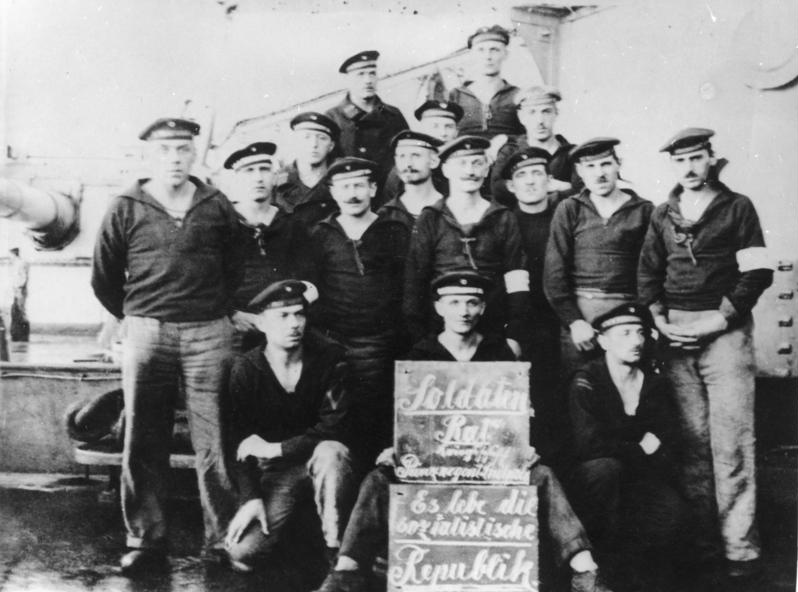

THE National Congress of Councils of Workmen and Soldiers, which convened in Berlin on December 16 and was dominated by the moderates, marked the end of the first stage of the German Revolution.

Simultaneously, the movement among the masses, the temper of the revolutionary proletariat, the tremendous problems which are pressing upon Germany and Europe, and the whole tendency of events as determined by the proletarian revolution in Russia and its influence upon the coming peace conference indicate that the beginning of the second stage of the Revolution is developing–the stage of the definite accomplishment of a proletarian revolutionary alliance with Soviet Russia, and the breaking forth of new international antagonisms, revolutionary war and civil wars.

The days preceding the convening of the Congress were marked by rumors of counter-revolution, even actual preparations, by the feverish activity of the revolutionary Socialists, by ministerial crises and the refusal of Dr. Solf to resign (which he subsequently did, however, being succeeded by another hack of the old regime), and by the German workers engaging in huge strikes and preparing to interfere in the process of industry. This economic activity of the masses is vital, for unless the masses develop a consciousness of economic power, the will to establish workers’ control of industry, the revolution will remain political, and become a wasted opportunity.

The Spartacus Socialists, a few days before the Congress met, promulgated a program wholly in accord with the revolutionary requirements of the situation: “Disarmament of all police officers, non-proletarian soldiers and all members of the ruling classes; confiscation by the Soldiers’ and Workmen’s Councils of arms, munitions and armament works; arming of all adult male proletarians and the formation of a Workers’ Militia; the formation of a proletarian Red Guard; abolition of the ranks of officers and non-commissioned officers; removal of all military officers from the Soldiers’ and Workmen’s Councils; abolition of all Parliaments and municipal and other councils; the election of a General: Council which will elect and control the Executive Council of the soldiers and workmen; repudiation of all state and other public debts, including war loans, down to a certain fixed limit of subscriptions; expropriation of all landed estates, banks, coal mines and large industrial works; confiscation of all fortunes above a certain amount.” This program, an immediate, practical program of action, may yet rally the revolutionary masses and would imply the dictatorship of the proletariat a great stride onward to Socialism, and the preparation of the revolutionary German proletariat for the decisive international revolutionary events that are coming.1

The Congress of Councils met on December 16, with a clear majority for the moderates and the petty bourgeois Socialists. It dodged every actual problem of the Revolution, being intimidated alike by the enormity of these problems and the threat of what the Allies might do under certain conditions. The Congress allowed itself, perhaps willingly, to be brow-beaten by Ebert and Scheidemann–while outside in the streets of Berlin raged the revolutionary masses who repeatedly invaded the Congress. By a vote of five to one, the Congress refused to allow Karl Liebknecht and Rose Luxemburg to address it with advisory functions, while essentially counter-revolutionary speakers were listened to and often applauded. The Revolution had been accomplished by the uncompromising use of Bolshevik methods and Bolshevik slogans, which the Congress now rejected in favor of petty bourgeois democracy.

The reactionary character of the Congress was indicated in the repeated attacks on the old Executive Committee which, heaven knows, was moderate enough. The old executive was too radical for the Congress. Barth attacked Ebert and the Government for its food policy but the Congress sustained Ebert. Ledebour, the left Independent Socialist, who still hesitates, however, accused Ebert of furthering counter-revolutionary plans, and stigmatized him as “a shameful smirch on the Government,” amid scenes of protest and disorder. But the Congress approved of the Ebert ministry–and the right Independents, Haase & Co., in spite of all, retained their membership in the government of the counter-revolution. The Congress climaxed its reactionary attitude by the election of a very moderate Executive Committee in accord with the Government, giving this committee power to “control” the Government–in the event, perhaps, that it might become radical!

Repeatedly, during the sessions, delegations of workmen and soldiers insisted upon being allowed to present demands, a right they insisted upon in spite of the oppositional attitude of the Congress. One delegation of soldiers demanded the dismissal of all officers and military control for the Councils. A delegation of workers, which was allowed to speak only after violent protests, presented the following demands: “That all Germany be constituted as one single republic; that all government power be vested in the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Councils; that the supreme executive power be exercised by the Executive Council; the abolition of the existing government; measures for the protection of the Revolution; disarmament of the counter-revolutionists; arming of the proletariat; propaganda for the establishment of a Socialist World Republic.” In spite of these revolutionary proposals, they were decisively rejected, the Congress adopting a hesitant, compromising, petty bourgeois policy.

The Congress was stampeded into deciding for an early convocation of the Constituent Assembly, the date being set for January 19 by a vote of 400 to 70, amidst cries from the gallery of “Shame! Shame!” and “Cowards, we shall teach you a lesson yet! You are robbing the people of the fruits of the Revolution.” The counter-revolutionary character of this stampede in favor of the Constituent Assembly was indicated in Scheidemann’s speech, who told the delegates “very plainly” that if the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Councils continued in operation unspeakable woe would befall Germany, worse even than what had been suffered already; they were bound to drift into Bolshevism, no matter how little they desired it, and they would transform Germany into a second Russia but worse than the latter, because in Germany there was more to destroy. The Independents of the right had nothing to say against this counter-revolutionary manoeuvre. The Soviets of the revolutionary masses made the Revolution, and they are to abdicate–in favor of petty bourgeois democracy. This would mean the end of the Revolution. Again, the issue is clear–Constituent Assembly and Capitalism, or all power to the Soviets and Socialism.

The Congress of Councils indicated a definite swing to the right, to reaction. The representatives of the masses acted in accord with the policy of the petite bourgeoisie and not in accord with the policy of the revolutionary masses. But the Congress was not decisive. There were indications, moreover, that the reaction is temporary: the majority Socialist organ, Vorwaerts, declared during the sessions of the Congress:

“It must be declared openly that there is danger of the whole government apparatus crumbling and the armistice and peace negotiations being broken off on the ground that no competent German Government exists, and then all Germany will be occupied by Entente troops.”

It is precisely this threat that is temporarily holding in leash the action of the masses. The majority Socialists and the bourgeois cliques are shamelessly using this threat, declaring that the Allies will never permit a proletarian government in Germany–and being willing, if necessary, to invite the intervention of the Allies against the Revolution. The proletariat wants peace; it dreads a new war, exhausted by the old, and a definite proletarian revolution might conceivably mean a new wars–revolutionary war against international Imperialism. Will the revolutionary masses develop new reserves and new energy for the great final struggle.

The German proletariat will realize more and more how hopeless is its position unless it definitely completes the Revolution. It will realize that the policy of moderate, petty bourgeois Socialism is offering the proletariat as a sacrifice to international Imperialism; and the realization of this fact will mean swift and drastic action come what may.

The German revolutionary proletariat has a mighty ally in the Soviet Republic of Russia, and in the awakening proletariat of the other European nations, particularly France and Italy. Soviet Russia has offered the Germany proletariat three million soldiers if a war against Entente Imperialism becomes necessary; and in this revealed the splendid strategy of Lenin–the peace with Germany, in spite of its onerous character, allowed revolutionary Russia an opportunity to recuperate and reorganize, to establish the conquests of the proletarian revolution, to organize a new Socialist army for its own defense and for the defense of Socialism everywhere. The censorship on news from Russia cannot hide the fact that the Soviet Republic is stronger than ever, that it has largely restored normal conditions, that it is securing new allies, and that it has the military strength to become a real factor in coming events. Already, the revolutionary war against international Imperialism is starting in the Baltic Provinces, particularly in Esthonia, and the further into these provinces the Bolshevik troops penetrate, the nearer they come to Germany, the easier becomes revolutionary co-operation between the German and the Russian proletariat.

Coming events will surely assume a giant character, may mean the flaring up of new revolutionary struggles…

In Germany itself the Spartacides are being strengthened by the counter-revolutionary trend of events. Reaction conquers, but out of reaction comes new revolutionary action. The Independent Socialists have split and this split has strengthened revolutionary Socialism. The economic crisis is acute, and strikes are becoming numerous, the workers making what the bourgeois consider “impossible” demands. The workers, moreover, are developing, hesitatingly and awkwardly, the tendency toward workers’ control of industry, but of this practical movement, determined by necessity, may develop larger doings. The proletariat is face to face with problems which life itself must and will compel them to tackle by revolutionary means. The impulse of the economic crisis plus the sinister plans of international Imperialism, and the international revolutionary opportunity will create new revolutionary currents, will instill new energy into the exhausted masses: and the Revolution again flare up into action. The Ebert-Haase Government of the counter-revolution, in spite of the approval of the Congress, is shaking, threatened by counter-revolution from the extreme right and revolutionary action from the left, from the betrayed masses.

End and beginning–they jostle each other in Germany. Will the German proletariat act, and assure the international Revolution?

1. Rosa Luxemburg, some time previously, published in Die Rote Fahne, the Spartacus organ, the following program: “The rebuilding and re-election of the local Soldiers’ and Workmen’s Councils; the constant session of these representatives of the masses, transferring real political power from the small committee of the Executive Council to the broader base of the Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Councils; immediately to call a national council of workers and soldiers to organize the proletariat of all Germany as a class; to organize immediately, not the ‘peasants,’ but the rural proletariat and small peasants, who as a class have thus far been outside of the Revolution; the formation of a Red Guard of the proletariat, for the defense of the Revolution and the organization of a workers’ militia in order to break the power of the absolutist and militarist police-state and its administration, judiciary and army; direct confiscation of landed property, especially the large estates, as a provisional first step to secure food for the people; immediately to call a Workers’ World Congress in Germany in order to make the Socialist and international character of the revolution sharply and clearly apparent, because in the International alone, in the world revolution of the proletariat, lies the future of the German Revolution.”

The Revolutionary Age (not to be confused with the 1930s Lovestone group paper of the same name) was a weekly first for the Socialist Party’s Boston Local begun in November, 1918. Under the editorship of early US Communist Louis C. Fraina, and writers like Scott Nearing and John Reed, the paper became the national organ of the SP’s Left Wing Section, embracing the Bolshevik Revolution and a new International. In June 1919, the paper moved to New York City and became the most important publication of the developing communist movement. In August, 1919, it changed its name to ‘The Communist’ (one of a dozen or more so-named papers at the time) as a paper of the newly formed Communist Party of America and ran until 1921.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/revolutionaryage/v1n11-dec-28-1918.pdf#page=6