A Bolshevik and Kronstadt sailor who became the leading figure in the Red Navy and hero of the Civil War followed by, in 1921, becoming the first ambassador to an independent Afghanistan offers this absolutely fascinating, and still relevant analysis of a Civil War that has, in many ways, not stopped since this writing.

‘The Civil War in Afghanistan’ by Fyodor Raskolnikov from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 9 No. 7. February 8, 1929.

Afghanistan is a country with a considerable historical past. Its small connection with the economy of the world, its centuries of artificial isolation, have preserved in Afghanistan quite a number of antiquated forms of feudal rule. The remnants of feudalism which may be found in abundance in China, India, Persia, and a number of other Eastern countries, have been preserved in Afghanistan in their original undisturbed form. The entire economy of the country is based on agriculture, in which again feudal property is predominant. Enormous masses of the population have not yet settled down to a regular tilling of the soil but carry on a nomadic pasturage. Every year at the beginning of spring tens and hundreds of thousands of herdsmen wander with their flocks and herds, their families, and their entire scanty possessions to the blooming mountain pastures (encountering on the way all sorts of obstacles and not infrequently warring against the settled peasant population), to return in the autumn to the lower-lying winter encampments. In the system of Afghan economy, the few and thinly populated towns play no important role. Despite the wealth of natural treasure concealed in the mountains of the Hindukush, mining is insufficiently developed. The industrial output, concentrated at Kabul, is yet in its infancy.

This backwardness in the development of productive forces determines the class structure of the country. The overwhelming majority of the population consists of peasants (engaged in agriculture, pasturage, and cattle-breeding). The peasantry lives in the utmost poverty, is subjected to spoliation and coercion on the part of the landowners, suffers under the incompetency of the officials, and has to wrest from nature every hand’s breadth of tillable soil.

The political power lies in the hands of the landowners, the so-called “sirdars”. The ruling class is connected with the mass of peasant population only by means of the individual links in the long feudal-bureaucratic chain.

Unter the conditions of this patriarchal manner of living, the heads of the clans and the elders represent the organised authorities.

In contradistinction to China, India, and Persia, where there is a pronounced national bourgeoisie, there is practically no middle-class at all in Afghanistan. Not only that there can naturally be no question of an industrial bourgeoisie, seeing that the few existing factories are in the hands of the State even the commercial bourgeoisie is still at an embryo stage. The entire foreign trade, which is mainly carried on via India, is (with negligible exceptions) in the hands of Indian merchants. At the same time it is possible in Afghanistan to observe the interesting process of a dovetailing of landed-property and commercial capital. Many landowners invest their land-revenues in commercial enterprises and employ the profits gained thereby in extending their landed property. While in Persia the voice of the bazaar exercises a considerable influence upon the policy of the Government, the small element of the Afghan commercial bourgeoisie possesses absolutely no political significance. The small number of industrial workers have not yet begun to feel themselves a special class and are thus altogether unorganised. They figure just as little in the political arena as do the artisans who are dispersed all over the country. The Islamite clergy, on the other hand, has long since grown used to exercising an important political influence, amounting in the main to a pronounced support of reaction.

In the past, when the cruel and despotic Abdur Achman or the sensual Habib Ullah still sat upon the Afghan throne, all proceeded on the lines of a well-ordered feudal State. The great sirdars guided the destinies of the country, the peasants sowed and reaped neath the sweat of their brows and paid the onerous taxes. From time to time the Government sent punitive expeditions to conquer the independent tribes of Kofiristan or of the more distant Balackstan.

Under cover of a [unreadable word] of its foreign relations British imperialism turned Afghanistan practically into a subject colony.

In 1919 there was a palace revolt in Afghanistan. One February morning Habibulah, who had been hunting in the surroundings of Jalalabad, was found to have been murdered.

What were the reasons for the overthrow of Habibulah? He had failed to take into consideration the changes and developments which the world war and the October revolution had brought about in the international position of Afghanistan. He continued to bow to the Viceroy of India. In the meantime, however, the war had weakened the authority of Great Britain, and the October revolution changed fundamentally the proportion of power in the countries immediately adjoining Afghanistan. Up to the October revolution Afghanistan was in the toils of the two imperialist allies Great Britain and Russia, which could at any moment suppress any Afghan attempt at national emancipation. After the October revolution the Soviet Union was practically at war with Great Britain. Habibullah did not understand how to exploit these international differences in favour of the national interests of his country, and for this incompetency he paid with his life. The rise of the revolutionary movement in India which set in in 1919, stimulated the activity of the Young-Afghan nationalists, who brought about a palace-revolt. The Young-Afghan party then placed upon the throne the third son of the late monarch, Amanullah-Khan, who was proclaimed Emir in defiance of the prior claims of his two elder brothers. At the same time, the brother of the murdered Habibullah, Nasrullah Khan, laid claim to the throne. A civil war ensued, but did not last very long, since the troops of Amanullah, supported by the peasant population, soon gained the upper hand; Nasrullah was taken prisoner and shortly afterward executed.

This civil war created a marked line of demarcation between the adherents of the old feudal conditions and the champions of a reconstruction of Afghanistan. The pious and reactionary pan-Islamitic leaders rallied round them all the conservative elements, from the feudal landowners to the Islamitic priests. The progressively-minded Amanullah relied on the peasant masses, on the army, and on the organised Young-Afghans, who were to the greater part descended from the more progressive of the small landowners.

The programme of the Young-Afghans contained the claim to the independence of Afghanistan as regards foreign politics, besides radical reforms in the country itself.

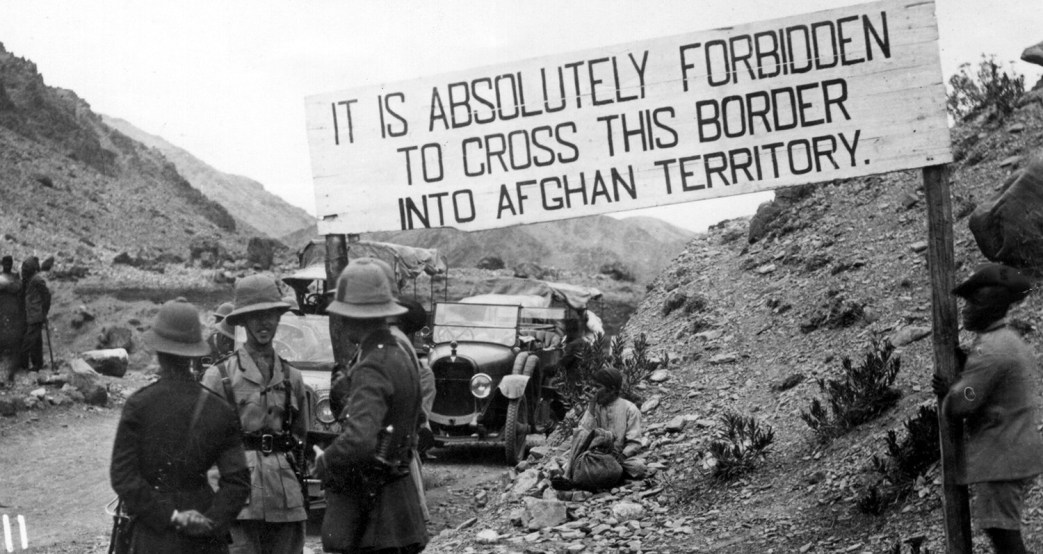

The first step of the new Government was the declaration of the independence of Afghanistan. But Amanullah was quite aware of the fact that such a declaration alone would not suffice. The country’s independence had to be fought for. He therefore turned all his arms against the usurper of Afghan independence, against British imperialism. A small but fanatical Afghan army invaded the frontiers of British India in the spring of 1919. Naturally the fight was unequal, since Great Britain was furnished with all up-to-date implements of war. The Afghan troops had to retire across the frontier and for a time even to leave the town of Hosta in British hands. But the internal position of India was very critical, for 70 million Indian Moslems openly sympathised with the Afghans and were inspired with such revolutionary zeal that the British could not profit by their victory. They saw themselves forced speedily to make peace and with heavy hearts formally to recognise the independence of Afghanistan.

Simultaneously with his declaration of war on Great Britain, Amanullah sent Lenin a telegram with the suggestion of an initiation of diplomatic relations. Soviet Russian most readily acceded to this proposal and was thus the first Power to recognise the newly gained independence of the young State.

The entire activity of Amanullah in regard to foreign politics was neither more nor less than an epoch of “enlightened absolutism under the specific conditions of a backward Oriental country”.

In the course of the past ten years, the Young-Afghans under Amanullah’s leadership effected some great reforms, which covered various fields of activity: 1. Creation of a native State industry (arsenals for the supply of the army, cement-works, etc.); 2. Enhancement of the cultural level of the country (development of the school system, delegation of teachers to study abroad, institution of female schools, etc.); 3. Reorganisation of the army; and 4. Emancipation of women (abolition of yashmaks, creation of women’s organisations, etc.).

These reforms were of progressive significance for Afghanistan, guiding the country in the direction of bourgeois development. The tragic of Amanullah’s case lay in the fact that he undertook bourgeois reforms without the existence of any national bourgeoisie in the country.

By his crusade against the feudal system and his exclusion of the clergy from political power, Amanullah naturally incited these classes against his reforms. The difficulty lay in the fact that he needed a firm class basis for his fight against feudalism and the Islamitic clergy.

The organic fault of all the reforms of Amanullah lay in the fact that they were devoid of an economic basis. These reforms, in themselves highly progressive, were extremely superficial and entailed no real advantages to the Afghan peasants.

But at the same time the reforms occasioned a tremendous outlay. The peasants, who had already plenty of taxes to pay, had to part with their last ruppes to pay for these expensive reforms. Taxation increased. Thus the tax due on assets rose by 400 per cent. in the course of ten years. Amanullah’s chief mistake lay in the circumstance that he opposed feudalism without effecting any comprehensive land reform.

Amanullah could easily have had the entire peasant population behind him, if he had taken the land from the feudal lords and given it to the peasants or if he had decreased the tax pressure on the peasantry by increasing that on the landowners.

Under the given circumstances the increased tax pressure caused the greatest dissatisfaction among the peasants, a fact the reactionary elements immediately turned to account.

The oppositional tendencies developing by reason of this pauperisation were exploited by the Afghan reactionaries for their own ends. Naturally it was not the entire peasantry that opposed Amanullah. The bulk of the peasant population observed an expectant neutrality, a section thereof rallied round the King. The fact remains, however, that the peasants of Kugistan and the Shinvari tribe rose in arms against Amanullah.

As an Oriental reformer, Amanullah has not infrequently been compared with Kemal Pasha. The later, however, was in a very much better position, since he effected his reforms in a less backward country. Therefore, based on the Turkish national bourgeoisie, he succeeded in destroying the Caliphate, separating the church from the State, and breaking the back of the clergy.

For lack of a firm social basis, Amanullah was not in a position to attack the clergy and religion with such determination. He went more cautiously to work, restricted himself to half-measures, left the “shariat” untouched, and merely renovated and [unreadable word] it a bit. Such an ambiguous position could not be without serious dangers.

The complicated national conditions in Afghanistan added to the complexity of the class struggle. There are in the country numerous tribes which are constantly at variance, thus the tribes of Shinvari and Mangal which have had a feud between them for centuries. Such differences have often been exploited by the Government.

The feeling of State citizenship is not very pronounced in Afghanistan. Each citizen is in the first place a member of a tribe and only in the second place an Afghan. Amanullah’s policy of centralisation aroused resistance not only on the part of the feudal landowners but also of entire tribes. His propaganda for national independence was highly comprehensible to the Young’ Afghan officers and students of the Kabul Academy, but failed to awaken an echo in the minds of the nomad tribes.

Finally, the policy of the British imperialists played a great role. The British Government could never get over its failure to subdue Afghanistan; which remained the sore point in British world hegemony. All the intrigues of British diplomats, from Lord Curzon to Sir Francis Humphrys, the Minister at Kabul, were directed towards bringing about a rupture of diplomatic relations between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. Threats and promises, secret notes and open ultimata, terrorist attempts and reactionary risings in a word, the entire arsenal of an experienced bourgeois diplomacy was employed to this end.

The British need a dummy in Afghanistan after the pattern of King Fuad of Egypt or of King Feisal of Mesopotamia. Amanullah is naturally not to be used in such a way. Once the British diplomats had recognised this fact, they had already decided to get rid of him.

During Amanullah’s visit to Europe last year, the rising was prepared and there can be no doubt but that Bacha-i-Sago, “famous” as a chief of banditti in the vicinity of Charikar, was in close touch with the British Legation at Kabul.

From the standpoint of war-preparations against the Soviet Union Afghanistan is a highly important base for the British. An independent Afghanistan represents a danger to the British possession of India, while on the other hand an Afghanistan under British souzerainty would mean a real menace to the Central Asiatic regions of the Soviet Union.

Amanullah has not yet abandoned the fight. If he regains his authority he will be obliged to broaden his social basis, to rely on the peasants, to effect a land reform, to lessen the taxation of the peasants and to carry on the fight against the feudal lords and the priests with greater determination than hitherto.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1929/v09n07-feb-08-1929-inprecor.pdf