A valuable study of conditions and politics in Greece a decade after defeat in the war with Turkey and the ‘September 11 Revolution’ from Kostas Karagiorgis, a major figure in early Greek Communism, then editor of Rizospastis, who would later play a central role as Communist military leader in the Resistance and Civil War.

‘The Situation of the Working Class in Greece’ by Kostas Grypos (Kostas Karagiorgis) from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 12 Nos. 57 & 58. December 22 & 29, 1932.

1. Introduction.

The present descendants of the ancient Greeks are one of the poorest peoples in the world. The diet of the Greek workers and peasants consists of bread, cheese, onions and olives. Ten years of uninterrupted wars (1912-1922) have, it is true, extended the sphere of action of Greek capitalism and brought in enormous war profits, but they have at the same time left behind as a legacy, 11⁄2 million refugees from Asia Minor and Thrace, for the most part poor expropriated petty bourgeois, peasants and workers and small traders, who are scattered over the whole of Greece and delivered over to ruthless exploitation by international finance capital. A further direct heritage from the war is the general post-war crisis of Greek capitalism, which of course is influenced and complicated by the international economic crisis. A characteristic feature of this crisis is the chronic agrarian crisis, which commenced immediately after the war and in the last four years has assumed disastrous forms. In trade and industry the first phase of the crisis (1922 to 1923 24) was followed by the relative stabilisation, which lasted till 1928-29. This new phase of the crisis, which commenced in 1929, involved not only agriculture, trade, industry and shipping, but since last year has extended to credit, finance and State finances. The currency has lost half its value, and the tariff walls are being raised to insurmountable heights. The deficit in the trade balance is growing, imports and exports are declining, and the deficit in the State budget will amount to 600 million crowns.

What is the situation of the working population in these circumstances? According to data derived from official sources, out of a population of 6,204,084 (1928 census) 250,000 are unemployed. Kotzias, the chairman of the big merchants’ organisation in Athen, estimates the number of those who “lack the barest necessities” at 700,000. There is hardly any unemployment benefit in Greece. The unemployment benefit which has existed hitherto for the tobacco workers is about to be done away with. The eight-hour day is recognised only in a very few industries, and even there it is not strictly observed. In a whole number of industries there exists a legal ten-hour day. Women and children work for ridiculously low wages. When even a reformist in the Labour Office of the League of Nations was appalled at the misery of the working Greek children, Mr. Vurlumis, a member of the government and wholesale fruit-dealer by profession, replied: “What are we to do with the children who have nothing to eat at home? We let them work!” Thousands of young people are working without any pay, “because they are learning”.

Professor Svolos, wrote as follows in the “Elevteron Vima” of June 2, last:

“It is clear that a State whose citizens are compelled to work right from their earliest childhood, and thereby become crippled as a result, a State in which the national industry is based mainly on low and often starvation wages, in which tuberculosis and malaria play havoc with the life and health of the individual, and, finally in which civilisation has not yet extended its power beyond the narrow circle of the rich classes and the central districts of the capital town and a few other towns, should have far greater obligations to fulfil towards the working population.”

This capitalist professor sees that the danger is greater than ever.

The lot of the peasants is even worse than that of the town workers. The small peasant is only nominally the owner of his property; in reality everything he has belongs to the agrarian bank, the money lender and the State. Professor Andreadis wrote in “Le Capital” of February 1932:

“The Greek tax-payer is weighed down mainly by the burden of direct taxes, and then by the indirect taxes, which are imposed on the most necessary articles of consumption, including bread, and are worse than in any other country in Europe.”

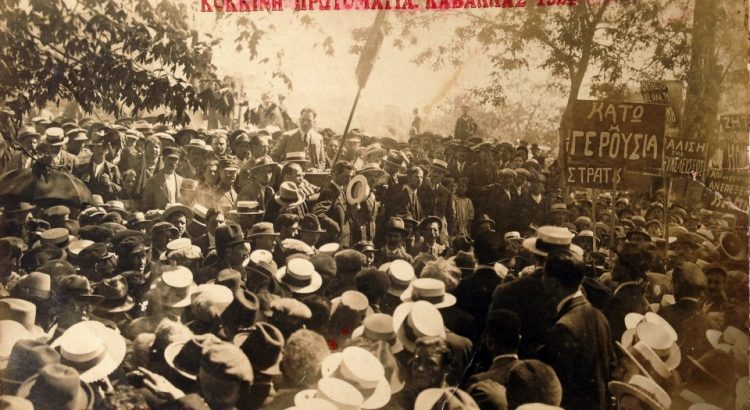

This enormous misery of the Greek working masses has not failed to call forth resistance on their part. The Greek workers replied to the first outbreak of the crisis in 1929 with a wave of strikes in which 60,000 workers took part. In the first seven months of 1932 the strikes reached almost the same extent. Important sections of the working class, such as the tramwaymen, railwaymen, tobacco workers and civil servants, joined in the struggle. Hardly any strike ends without collisions with the police, wholesale arrests, killed and wounded. The peasants flee to the mountains in order to avoid paying taxes, beat up the tax collectors and set fire to the tax offices. The hunger marches of the peasants have shaken and are shaking the whole country, in particular Thessaly and Macedonia.

The general revolutionisation of the toiling masses is shown by the results of the elections held on September 25, when the Communist Party achieved a big success and made considerable progress towards winning the majority of the proletariat and the toiling masses.

2. The Tobacco Workers.

The men and women workers engaged in the tobacco industry constitute an important part of the Greek, and also of the neighbouring Bulgarian, proletariat. They occupy a prominent place in the history of the Balkan proletariat. The first strike of the tobacco workers broke out in Salonica in the time of the Turkish feudal rule, after the revolution of the Young Turks in July 1908. At that time the first “solidarity fund” was founded by Jewish tobacco workers. The tobacco workers also formed the main strength of the “Socialist Federation”, which helped to bring to birth the proletarian revolutionary movement, in Macedonia. In 1912 there took place the first Congress of the tobacco workers of Eastern Macedonia. Since 1918, the tobacco workers have formed the main portion of the Greek proletariat. Numbering 55-60,000 and possessing a firm socialist ideology, they dominated central and Eastern Macedonia, Thrace, Thessaly and Agrini, and played a considerable role in Piraeus and Mytileni. The tobacco workers’ union was founded at the beginning of 1919 at the first Congress of the tobacco workers in Volo. Since then hardly a year has passed without a strike of the tobacco workers. The period of relative stabilisation of Greek capital was accompanied by a broad offensive of the tobacco workers in order to improve their economic position. By means of this struggle, which found its strongest expression in the big strike of 1924, they achieved an agreement with the State according to which the daily wages of the tobacco worker must amount to seven-twenty-fifths of an English gold Pound, and those of the working woman to 40 per cent of the man’s wages.

A further result of the fierce struggles was the founding six years ago of the tobacco workers insurance, the first insurance of this kind in Greece. The tobacco workers had to pay the same contributions as the employers, i.e. 6 per cent., and later 7 per cent., of their wages. It is mainly an insurance against sickness, and only partly against unemployment.

The following conditions accompany the unemployment insurance of the tobacco workers: in order to qualify for unemployment benefit a tobacco worker must have worked 125 days, but benefit is only paid for 60 days in the year.

The present phase of the crisis of Greek capitalism, which commenced in commerce and industry in the year 1929, has had disastrous effects on the tobacco industry. Greek tobacco, which in 1929 constituted 53 per cent. of the total production of oriental tobacco, in 1931 constituted scarcely 37 per cent., being ousted by Bulgarian and Turkish tobacco. From 1929 to 1931, the area under tobacco declined by 31 per cent., output receded by 46 per cent., exports by 14 per cent., whilst since 1927 the prices fell by 70 per cent. Between 1929 and 1931, the number of tobacco planters in Thrace and Macedonia declined from 73,983 to 51,494, i.e. by 31 per cent.

The disastrous crisis caused the employers to launch a fierce offensive against the rights that had been won by the tobacco workers. But the workers immediately replied with a counter-offensive. In 1929 a general strike of the tobacco workers broke out, during the course of which it came to barricade fighting in Agrini. By this means the workers not only repelled the attack of the employers, but also succeeded in getting the period of unemployment benefit extended from 60 to 75 days, and the qualifying period reduced from 125 days work to 100 days.

Nevertheless, since 1930 the employers, taking advantage of the rapidly growing unemployment and the dissolution of the tobacco workers’ union, following a decision pronounced by the Courts, succeeded in depriving the tobacco workers of the economic rights they had won. The agreement, according to which the daily wages of the men workers should amount to 7/25ths of a Pound (105 Drachma) was broken. The gates of the tobacco factories were opened to workers who were paid 85, 70, 60, and last Summer 30 and even as little as 18 drachmas a day. This means a wage reduction of 40 to 65 per cent. Sick benefit is only granted to workers who have worked 100 days. The others can simply die in the street. Maternity benefit has been done away with. The convalescent home in Thassos has been closed. Over 3000 women tobacco workers do not receive any sickness and unemployment benefit although they have to pay 6 per cent. of their wages into the insurance fund. Everywhere the eight-hour day is exceeded. All trade union action in the factories, even the payment of trade union contributions, is prohibited. Hundreds of tobacco workers are in prison and in exile. Finally, a month ago the government issued an order doing away with payment of unemployment benefit to the tobacco workers, whilst at the same time rendering generous financial aid to the tobacco manufacturers.

The black spectre of hunger is haunting the tobacco districts of Eastern Macedonia, Thessaly and Thrace. Not only the tobacco workers, but the whole of the working population of these districts are drawn into the vortex of the crisis. Last Summer over 3000 tobacco workers carried out a determined strike struggle. The monstrous brutality with which the government is proceeding against the tobacco workers will not prevent them from again engaging in a general strike.

3. The Industrial Proletariat–Miners–Seamen.

After the end of the wars, which for Greece lasted until 1922, Greek capitalism, thanks to the huge profits it acquired, and by exploiting the cheap labour of the refugees, was able to build up an industry far and away beyond the pre-war level. Greece is today the most industrialised country in the Balkans, although as yet it does not possess any heavy industry.

It is absolutely impossible to ascertain the exact number of the Greek industrial proletariat, as the State statistics are very poor. According to the latest census of all workers and employees who were at work on 4th September 1930, the number of workers, employees and State officials, both men and women, was 350,000. Of these, 161,000 are industrial proletarians, 8,000 miners, 25,228 transport workers, 40,235 tobacco workers (of whom 16,661 are women), 66,781 office and bank employees, and 45,000 civil servants. Seamen and agricultural workers are not included in this census.

One cannot speak of social insurance in Greece. Only the 45,000 civil servants come under a system of insurance, which is as inadequate as was that of the tobacco workers.

After the outbreak of the crisis in 1929, the capitalists started a fierce offensive against wages and the miserable insurance which existed in the case of the tobacco workers and civil servants. Owing to the lack of organisation of the Greek workers and the fact that the big trade unions had been converted by the reformist leaders into an appendage of the State, and also owing to the great weakness of the red trade unions, the Greek bourgeoisie were able for the greater part to realise their programme. There is no branch of industry in. which wages have not been reduced by at least 30 per cent. Wages in the textile industry have been reduced 40 to 50 per cent. Up to 1929 there existed a legal nine-hour day in the textile industry, which was extended to ten hours until 2 months ago, when it was finally extended by law to 11 hours. The collapse of the carpet industry has brought tremendous misery to the carpet weavers, mostly young women.

The “Power” electric company in Athens is a ruthless exploiter of the electric and transport workers. This exploitation has assumed a colonial character (military drill, speeding up, engagement of large numbers of temporary workers, dismissals etc.). The repeated attempts of the “Power” company to reduce wages by more than 6 per cent. have fortunately been frustrated by strikes. Similar measures were adopted against the railway workers, who, in addition to a 6 per cent. wage cut, have had their holidays reduced by half, and many of them have been dismissed. It is now announced that the European railways intend to have the international trains running on Greek territory manned by their own staff, so that about 1500 Greek railway workers can be dismissed. For dock workers there has been introduced a State “Autonomous Harbour Board”, which rationalises work according to fascist-military system, i.e. thousands of workers who had worked in the docks for years have been dismissed, and wages have been reduced by 30 per cent.

In the Greek mines in Naxos, Chalkidike, Lavrion etc., which for the greater part are run by foreign capital, over 10,000 proletarians are employed under the most frightful wage and working conditions. Accidents with killed and wounded are, of course, a daily occurrence. As a result of the earthquake in Chalkidike, which destroyed the Stratoniki mines, about 1000 workers were rendered unemployed and are delivered over to starvation without receiving any relief or compensation.

The seamen, who constitute a strongly developed and militant part of the Greek proletariat, have since May 1930 been forced to accept wage cuts amounting to 40-50 per cent. There are 7000 unemployed seamen in Piraeus and other big seaports. As Greek shipping has been severely hit by the crisis in the last seven months and many very big ships are lying idle in the docks, unemployment among the seamen will increase tremendously this year.

4. Refugees-Civil Servants-Unemployed.

The immigration of refugees from Asia Minor, East Thrace and of Greeks from Bulgaria to Greece constitutes a special and unprecedented social-political phenomena. 11⁄2 million people were suddenly torn from their old surroundings, and settled in North Greece, in the sterile, malaria-ridden, mountain districts. This settling in Greece meant a sudden proletarianisation of the masses of refugees who, for the main part, consisted of urban petty bourgeois and peasants of all categories. This new proletariat, devoid of all class consciousness, was unable to play a revolutionary role in the years so critical for Greek capitalism following the disaster in Asia Minor. By means of the first agreement regarding the exchange of population, according to which compensation amounting to the value of the property left behind in Turkey was to be paid to the refugees, the Venizelos party fostered the illusion among the masses, consisting mainly of petty bourgeois, that they would regain their former material basis and no longer be looked down upon as “mere workers”. The League of Nations supported this agreement so long as it appeared necessary to it in order to secure the so-called refugee loan, amounting to millions of English pounds. In June 1930, following a new agreement between Venizelos and Mustafa Kemal Pasha, all further payments of compensation to refugees ceased. The profound ferment among the masses of refugees shows that they are no longer the reactionary wall which they constituted hitherto, but that they are now rapidly taking their place in the revolutionary movement of the workers and peasants.

The present situation of the masses of refugees has become worse. The barracks in which they live, the cattle and farming instruments of the peasants are mortgaged to the European and American capitalists, to whom they have to pay compound interest. The camps of the refugees in the towns, a heap of dirt, tumble-down huts and rags, certainly constitute at the moment the most miserable human habitations in the whole of Europe. There are absolutely no sanitary arrangements. Water for drinking and washing brought by motor lorries and distributed in tin buckets. Prostitution and venereal diseases are rife. The economic cris which has prevailed in Greece for three years has, of course, greatly aggravated the desperate position of the masses refugees.

The number of civil servants in Greece is about 45,000 special category of them are the so-called “auxiliary” officials, who for years have lived under the constant threat of dismissal. The first declaration of the Tsaldaris Government consisted in the announcement that it would dismiss without compensation most of the auxiliary officials. When Venizelos came into power in 1928, he promised the civil servants that the Government would provide the sum of 180 million Drachma for the purpose of increasing their salaries. But Venizelos not only did not grant the 180 million but reduced the salaries of all civil servants by 6 per cent., although the salaries had already lost 40 per cent. of their purchasing power owing to the depreciation of the drachma. Promotions were practically abolished on grounds of economy. Most of the 13,000 elementary school teachers do not earn even 2,000 drachma a month (about £3). The Federation of Civil Servants was dissolved and any centralised organisation of the civil servants was prohibited. A special law forbids them to strike, and a further law provides that any civil servants going on strike are to be immediately called to the colours and placed under military law.

The civil servants however have not tamely submitted to this offensive. A considerable part of them are led by the Left All-Greek Civil Servants’ Committee, which recently held at successful national Conference at which it was decided to organise the fight of the civil servants. A few months ago there took place a strike of the post, telegraph and telephone employees, which compelled Venizelos to resign.

There are no official statistics in Greece regarding unemployment. The factory statistics for 1930 show a 30 per cent. increase in unemployment compared with 1928, and the crisis has developed even more rapidly since 1930. In addition, the number of workers who are employed only two or three days a week is very high.

There is no State unemployment relief in Greece. Led by the Communists the unemployed movement enforced some trifling relief from the municipalities.

The only hope of the unemployed is their more systematic and strong mobilisation under Communist leadership. The slogan: “Unemployment relief out of the military budget”, which is rousing the masses of the unemployed, will in the near future form the basis for more intensive fights of the unemployed together with the employed workers.

5. The Situation of the Toiling Rural Population.

More than 50 per cent. of the national income of Greece is derived from agricultural production. According to the last census, held in 1928, out of a total population of 6,204,683, 3,598,716, i.e. 58 per cent. belong to the rural population. Further, Greece differs from the rest of the Balkan States in that it does not produce sufficient corn for its own consumption; its main products are four luxury products--tobacco, sultanas, wine and olive oil–the greater part of which is exported.

The present stage of the chronic agrarian crisis, which has existed since the end of the war, is expressed in the reduction of the area under cultivation, declining production, falling exports and the drop in the price of all agricultural products.

In the case of tobacco there was a decline in the production, the exports and prices already in 1928. Since 1929-1930 the area under tobacco has declined by 38 per cent., output has fallen by 46 per cent., exports by 14 per cent., while prices have declined by 70 per cent. since 1927.

Before the war Greek sultanas accounted for 75 per cent. of the world output. After the war Greece’s share in the world output of sultanas was reduced by 30 per cent. owing to development of sultana production in other countries, especially in California and Australia. The position in regard to sultana production is rendered still more difficult by a law which came into force in 1930, according to which 20 per cent. of the harvest must be retained in the country and delivered er to the spirit industry. This constitutes a legalised robbery thousands of vine-growers for the benefit of a few spirit distilling firms.

In 1929 to 1931 the export of wine declined by 68 per cent. The olive oil output of Greece, which forms 18 per cent. the world output, declined by one half in the period from 1929/31, as did also prices.

60 per cent. of the peasants are engaged in grain production. In 1928 grain production amounted to 356,129 tons, and in 1930 to only 264,200 tons. The decline of grain production is due to the backward methods of farming and the exploitation of the peasants by the Greek fertiliser industry, which enjoys a sort of monopoly, although its products are not only useless but even directly harmful, as was officially stated in Parliament. As a result, Greece is compelled to import 5-600,000 tons of grain a year, an item which accounts for 40 per cent. of the deficit in the trade balance.

The following quotation from the “Oekonomikus Tachydromes” of April 1932 gives a general picture of the decline of agricultural production:

“Last year the output of grain declined so much owing to natural disasters, that the crops did not suffice to meet the peasants’ requirements in the way of food for themselves and fodder for their cattle. A great part of the vines were destroyed by frost. The harvest which was got in remains unsold as a result of the crisis, and prices are steadily falling. There is also no demand for tobacco, olive oil or wine. They lie unsold in the warehouses and peasant houses, and their prices are constantly sinking.” Various so-called “autonomous protection organisations”, which were founded by financial and industrial capital with the support of the State, have the task of rescuing the peasants and promoting national production, i.e., increasing the exploitation of the working rural population to the utmost limits. These institutions have in their hands the export monopoly for sultanas and a very considerable part of the tobacco industry and commerce.”

A further fact tending to worsen the situation is the difference between the prices of industrial and agricultural products. Whilst since 1928 wine has fallen in price by 30 per cent., sultanas by 50 per cent. and tobacco by 70 per cent., bread has continually risen.

The exceedingly high taxes complete this depressing picture. Last year and in the current year the taxes amount to 50 per cent. of the net income of the working peasants. When the peasants hear of the arrival of the tax officials, they flee to the mountains,

A further form of oppression is forced labour for the municipalities. Refusal to perform this work is punished by fines.

This whole situation is leading to a rapid differentiation in the villages. The small peasants form a vast mass who never possess actual cash but only the paper money of the Agrarian Bank. Last year, 31 per cent. of the Macedonian and Thracian tobacco planters completely abandoned the cultivation of tobacco.

There are no statistics regarding the landworkers, hardly any of whom are organised. Thousands of charcoal burners, tree fellers etc. are working on the big forest lands belonging to the State, the monasteries and the landowners. There are no fixed rates of wages. The workers undertake 15 hours hard work in return for a sum arbitrarily fixed by the employers which only suffice to purchase a piece of bread.

The agrarian crisis vividly reveals all the class contradictions in the rural districts and causes a rapid revolutionisation of the poor and middle peasants and agricultural workers. There is no district in Greece without hunger-marches of the peasants. The tax collectors’ offices are set on fire. The slogan: “Free maize!” resounded last Autumn and Winter throughout the whole of Macedonia and Thessaly; granaries were stormed, in Thessaly. Hundreds of revolutionary peasants have been sent to prison or banishment islands.

The Communist Party of Greece is exerting every effort in order to mobilise the working rural population for the fight. The chief weapon in this fight in the rural districts is the landworkers trade unions and the fighting committees of the working peasants.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1932/v12n57-dec-22-1932-Inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1932/v12n58-dec-29-1932-Inprecor-op.pdf