In a four-part series, Joseph Freeman introduces us to the ‘Gomez’ and ‘Romero’ families, activists in the cigarmakers’ union and Communist Party members, and through them the larger story of Tampa’s fighting cigarmakers.

‘Tampa, Florida’ by Joseph Freeman from The Daily Worker. Vol. 11 Nos. 112-15. May 10-14, 1934.

GOMEZ, a delegate to the state convention of the Communist Party recently held in Miami, asked me to look him up when I got to Tampa. I found him living above a garage on a tree-lined street in Ybor City with his wife and year-old son.

Gomez is 25, works in an office, wears close-cropped hair above a sensitive, serious, intelligent face. He reads everything and asks questions about John Strachey, Grace Lumpkin, Granville Hicks. He is continually talking about problems that arise in organizing the workers. He remembers every victory of the Tampa cigarmarkers and every mistake. We must not make that error again, he is always saying. His activity, in terror-stricken Tampa makes it necessary to conceal his real name.

We shake hands with his wife and baby; the baby is also serious. His mother is worried because everybody at first sight takes him for a girl. We assure her that eventually he will grow hair on his chest, be a working-class leader, a real hombre, and nobody will ever mistake his gender.

“NOW TAKE THIS N.R.A. BALONEY” Gomez’ mother, 45, smiles through her glasses, asks us to stay to supper. She walks back and forth between the kitchen and the living room explaining the life of Tampa workers. She has worked in cigar factories since she was 13, and her father. worked in them before her. She was born in Tampa, speaks good English, but better Spanish, and alternates between the two tongues.

“Now take this N.R.A. baloney,” she says. “Cigar workers are supposed to get a minimum wage under the code–$12 a week. They get paid by piece-work but are supposed to get no less than $12, no matter how few cigars they make. But the bosses get around that. They pay you for the cigars you make at a low rate; you average, let’s say, five or six dollars a week. Then they make you sign a paper that you received $12. That’s a lie; but you got to sign the paper or get fired.”

YOUNG GOMEZ waits until his mother goes back to the kitchen and says: After the 1931 strike the bosses and the government bust up the Tobacco Workers Industrial Union; it was a fine union with about 6,000 members, truly revolutionary; and they smashed it. They deported the secretary, Jose Ferras, to Cuba. The police raided the union headquarters, grabbed the membership list and confiscated the funds, thousands of dollars contributed penny by penny by the workers. Immigration officers visited the homes of workers who were not American citizens and threatened them with deportation if they did not drop out of the movement.

“I can give you an example of this N.R.A. stuff,” said Mrs. Gomez coming in from the kitchen. “At Berriman Brothers, a cigar factory in Palmetto Beach, on the Hillsboro River, they actually have two lines on pay day; one for workers who made $12 or more at piece rates, and one for workers who made less but must sign papers saying they were paid $12. One worker protested. He said: ‘You are robbing me; I am entitled to $12; the government says so. The foreman says: ‘Yea? What are you going to do about it?’ The worker says: ‘I am going to call a cop…”O.K.,’ the foreman says, ‘here is your goddam twelve dollars–you are fired.'”

“WE HAD WONDERFUL PICKET LINES”

“It was tough,” young Gomez said, “to have the union smashed after the magnificent strike of 1931. We had wonderful picket lines. The Labor Temple was crowded every night and speeches went out through loud speakers to overflow meetings in the street. We flew the red flag on the roof of the Sanchez y Haya factory…The terror is very bad now, but I guess we made some mistakes in the conduct of the strike. We must avoid those errors in the future…”

Mrs. Gomez comes into the open kitchen doorway peeling platanos. Plumply smiling through the glasses, she says: “And the bosses own the cafeterias near the factories, and the workers got to eat there or get fired. They take your food bill off your pay; you got to eat there whether you like it or not.”

In 1933, young Gomez continues, a new union was started, the local independent union–Union Local Independiente de la Industrial del Tobaco, with about 5,000 members. It had a left-wing program: militant class struggle, solidarity with the workers of the world. But many of the workers had illusions about the N.R.A.; they were taken in by the Roosevelt demagogy. At its own expense the union sent a delegation to see General Johnson in Washington about a code for the tobacco workers.

A YOUNG, fat, dark, good-looking girl came in; we were introduced to her, a daughter of the Romero family. She corrects Gomez: “The union sent two delegations.”

That’s right; there were two delegations, and both of them got nothing in Washington. But here in Tampa the police started a vicious terror against the union, and against the Unemployed Council which we started last year. They were especially vicious against the Council because it drew in many Negroes; for the first time in Tampa many Negroes joined with white workers in one organization. We never saw so many Negroes in the Labor Temple. When conditions became intolerable, the union began discussing a strike. The police came to union meetings and ordered: there must be no strike; the city of Tampa does not want a strike. But the union voted for a strike despite these warnings. The police retaliated with a series of brutal raids on the union and the Unemployed Council. Many white and Negro workers were arrested; one Negro had his ear cut off in the police station; the cops told him this was a sample of what would happen to all Negroes who listened to the Reds.

Mrs. Gomez, coming out of the kitchen, said: “And when a boss or foreman likes a woman, she’s got to give in to him. If she don’t, he will fire her, and all her friends and relatives.”

THE STRIKE MET WITH DIFFICULTIES

The strikers demanded union recognition, young Gomez went on, the restoration of the readers abolished in 1931; a 30 per cent wage increase bringing wages back to the 1929 level, with additional increases commensurate with the rising cost of living…The strike met with a lot of difficulties; some of the union leaders were young and inexperienced; they were afraid of exposing the N.R.A. for what it is, the worst form of exploitation we have had yet. These leaders played into the hands of the manufacturers, who used the N.R.A. for all it was worth. Rank-and-file committees led by Communists had to issue leaflets criticizing these leaders.

From the kitchen door Mrs. Gomez said: “I don’t know what they pay in all the factories, but I know that in the Havana-Tampa, owned by that bloodsucker Woodberry, the average wage is about $6 a week.”

II.

BUT that wasn’t all, young Gomez continued. The growth of our union and the spread of the strike gave the A.F. of L. some ideas. Their southern organizer, a palooka named George L. Googe, came down here to start an A.F. of L. union. The capitalist press gave him plenty of good publicity and the city government and the bosses gave him a helping hand. Googe set out to break the strike. He urged our workers to quit a union that leads them to jail and deportation. Join the A.F. of L., he said, which has friends in the government of Washington and Tampa; we will get you higher wages while you stay peacefully at home. Our strike lasted three weeks. Police terror, N.R.A. illusions, and the A.F. of L. propaganda finished our union.

There was noise in the doorway; people came in and we were introduced: Mrs. Romero, a stocky Mexican mestizo in her fifties, brown-faced, intense, with steady grey eyes; her son, Vesper, now almost 17; her daughter Yorkina, now 19; finally, Vladimir, now almost 13, with a beautiful, mobile, spoiled, clever face, always smiling. His mop of black hair reminds you of the young Sergei Eisenstein. I am giving the real name of the Romeros, loved by the workers of Ybor City; they have served jail sentences; their story is on record.

With the Romeros came Paul Lima, Communist candidate for governor of Florida in the last elections. He is a young, alert, unusually serious Latin with scraggly down on his upper lip.

“After the strike was broken,” Lima takes up Gomez’ story. “the cops started their reprisals. They raided comrades’ houses, arrested them, beat them up something terrible. Police Chief Logan in person led the raid on my house. I expected it; whenever the cops come down on the workers, they visit the houses of John and Paul Lima; so one day before the raid I moved our mimeograph on which we print leaflets and manifestoes to another house…The A.F. of L. got about 3,000 of our members by their fake promises; but as months passed and nothing came of those promises, many members dropped out…While the A.F. of L. fakers were helping the bosses break our union, a socialist faker, named Paulnot, organized the so-called Unemployed Brotherhood to take members away from the Unemployed Council. He has the co-operation of the police, which protects his meetings while breaking up ours, and of the local authorities who let the Brotherhood meet in schools while closing down our halls. The terror has reached the point where Police Chief Logan announced that there will be no more meetings because the Reds favor intermarriage of whites and blacks and the good people of Tampa will not stand for that.

“Besides,” said Mrs. Gomez from the kitchen, “they come to a workers’ house, grab him in the middle of the night, take him to the police station, and in the dark they let him out into the street where the bosses’ hired gangsters beat him up. Do you remember, Paul, the way they beat up Hy Gordon? They smashed his face, and broke his arm with revolvers. He was laid up for months in the hospital. Then they had the nerve to hand him a bill for medical treatment. He never paid it. He said: ‘Send that bill to Mayor Chaney.’

Of course, said young Gomez reflectively, we made some tactical errors; we must not repeat them: we must learn to work illegally, to build the movement under conditions of terror. Above all we must not stop with Tampa; we must organize the whole state of Florida.

ASKED Mama Romero: How old are you? You don’t have to tell me exactly, just in general; and she said: I am exactly fifty-three.

I am calling her Mama Romero not because she has six children, all of them, from 32-year-old Carolina to 13-year-old Vladimir, militant class-fighters; not even because her face, lined with suffering and struggle (yet now and then flashing echoes of the coquetry of her youth) is deeply that of a working-class mother. She is in spirit the youngest and most vigorous of the Romeros; I am calling her Mama Romero in order to distinguish her from the other Romeros.

MAMA ROMERO’S STORY

I asked her to tell me in Spanish–her English did not meet the needs of her narrative the story of her imprisonment during the great strike of 1931. Here is the gist of the story:

The revolutionary tobacco workers of Tampa asked the city authorities for a permit to hold a parade on Nov. 7. The permit was granted. Then the mayor asked what the parade was for; it was to celebrate the 14th anniversary of the October Revolution. Hmm…Hmm…Where did the parade intend to go? It was going to pass down Center Ave…Hm…That settled it. Center Ave. is the main stem of the Negro section; no parade to celebrate revolutions; no parades among the Negroes; no permit.

The workers decided to hold an indoor celebration in the Labor Temple. Mama Romero went to the meeting accompanied by her daughter Carolina, then 29; her daughter Yorkina, then 16; and her son Vesper, then 14. Near the Labor Temple, a comrade stopped her: the cops have just arrested your son Vladimir.

Vladimir, the beautiful young devil, was at this time only ten; but he was active in the Pioneers. His father, a Mexican worker, a fighter in the revolutionary movement, had named him after Lenin.

Mama Romero, followed by Carolina, Yorkina and Vesper, ran down the street, seized a policeman who was holding Vladimir by the neck.

“Why are you arresting my son? He is only a baby!”

“I don’t give a damn if he is your son,” the cop said. “He’s been selling the Daily Worker and other Red trash. He’s going with us.”

“If you arrest my baby, you will have to arrest me, too!”

“O.K., lady, come on.”

A cop grabbed Mama Romero by the arm. Her two daughters and her son started to run toward the Labor Temple: “Companyeros! They are arresting Mama!” The cops chased after Vesper and the girls and arrested them. The Romero family was dragged off to the patrol wagon. Workers came running out of the Labor Temple, nearby houses; a big crowd gathered in the street.

“Look, comrades!” Mama Romero shouted. “See how they treat women in the land of liberty, the land of Washington and Lincoln!”

Cops twisted Mama Romero’s arms; one of them clapped his hand over her mouth. The Romeros were shoved into the patrol wagon. It was jammed with other comrades arrested during the meeting. The wagon started for the city jail. Mama Romero and the comrades sang all the way at the top of their voices: Bandera Roja, the International.

III.

LATER Mama Romero learned what had happened at the Labor Temple. A policeman had grabbed Vladimir and other Pioneers selling the Daily Worker and the Labor Defender. He dragged Vladimir toward the hall.

Felix Marero, a comrade standing in the doorway, protested: “What in hell do you mean by arresting a ten-year-old kid? Let him go!”

The cop hit Marero and Marero shot his fist into the cop. Whistles shrilled. A lot of cops came rushing into the hall; they fired revolvers into the crowd of workers. A policeman was shot, wounded; another was clipped by a brick…

From the city jail Mama Romero and her son Vesper and her wo daughters and the other comrades, 17 prisoners in all, were taken to the county jail. Vladimir had been released. The women were separated from the men, segregated with other white women on the third floor of the coop.

The next day a woman from the Juvenile Court came: What are your children doing here? They are minors. I must get them out…After spending 24 hours in jail, 16-year-old Yorkina and 14-year-old Vesper were released; but Mama Romero and her oldest daughter Carolina and 13 other comrades were kept in jail for two months without trial.

On Jan. 2, 1932, they were finally brought to trial before a picked jury of native whites, hostile to revolutionary organizations, prejudiced against Latins, bitter against those who try to organize the Negro workers. The witnesses for the prosecution were cops, full of the usual unscrupulous lies.

The defense put Yorkina on the stand to testify for her mother. She took her oath without protest from the prosecutor, went through her testimony. left the stand. Suddenly the prosecutor called her back.

“Do you believe in god?” “I do not,” Yorkina, said. “Then how did you dare to get up on this witness stand and take a false oath?”

“I did not swear by god; I affirmed; I spoke on my word of honor.”

The prosecutor turned to the jury: You see, gentlemen, the child does not believe in god. Whose fault is it? Who corrupted her? Her own mother! That is the kind of woman we are up against.

The judge ruled: Yorkina swore falsely; her testimony must be stricken from the record.

Throughout the trial, detectives sat near the jury box, commenting in stage whispers about the testimony of the defense witnesses. You could hear their hoarse voices through the court room: that’s a lie, that’s a lie…

Mama Romero was not allowed to take the stand.

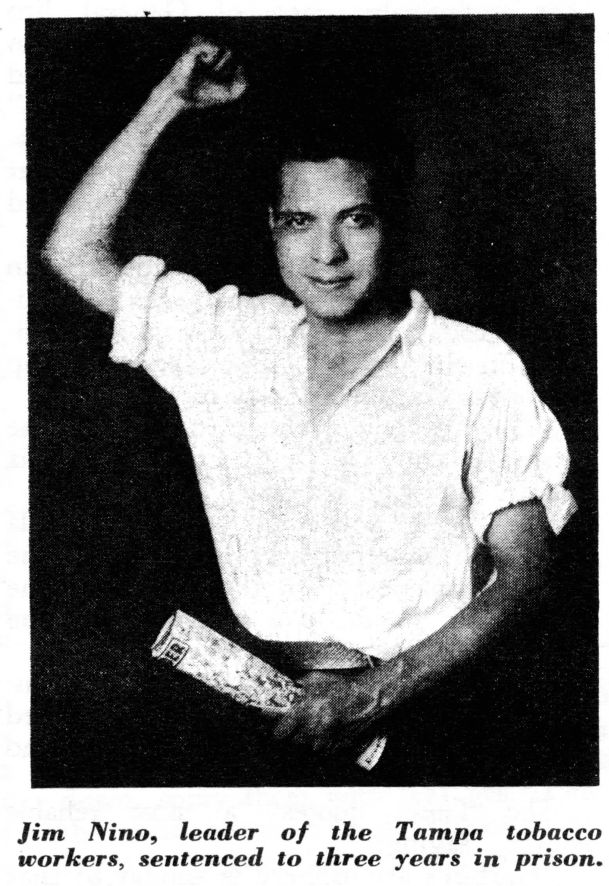

THE defendants were found guilty. Those who were not American citizens were deported: Jim Nine to Mexico, Enrique Bonilla and Carlos Lezama to Uruguay. Two year sentences were handed out to Felix Marera and Caesario Alvarez; longer sentences to McDonald and several other comrades. Eight, including Mama Romero and her daughter Carolina, were sentenced to a year and a day in the state pen at Raiford.

“DANGEROUS CHARACTERS”

The Romeros were not allowed to see their relatives or even to phone them. They were put in with 20 white women serving time for stealing. forgery, killing their husbands. The matron called all the prisoners together, and, pointing to the Romeros, said:

“These women are dangerous characters. They are Reds, Communists. Have nothing to do with them. Don’t talk to them; don’t listen to them; keep away from them; they are no good.”

FOR nearly a year Mama Romero and her daughter remained in the pen. They worked, sewing prison clothes; they had bad food and little of it: salt pork, two ounces of sugar a week, beans. The women prisoners were compelled to cook their own food; every day they had to sew 12 pairs of prison pants.

After the first few days, Mama Romero and Carolina began to talk to the other women prisoners. At first they would not listen; later they softened; then they paid careful attention. They got to like the Romeros. They sat hunched over the whirring sewing machines listening to Mama Romero explain how the church enslaves workers and how Communism frees them. There came a day when the women prisoners stopped going to chapel. The matron yelled at them, cursed the Romeros, the dirty Communists, but the prisoners stayed away from the services.

“The matron is crazy,” the prisoners said to Mama Romero. “You are not bad, you are very good. If all Communists are like you, they are not dirty at all; they are very fine people.”

On Dec. 21, 1932, the Romeros were released. “You and your daughter should never have been locked up in here,” Captain Dobbs of the prison guard said to Mama Romero as he let her out. “You were framed.”

FROM the Tampa Daily Times, March 31, 1934: “Forward march! The West Coast Better Times parade and pageant will get under way at seven p.m. sharp Monday. From the skies will come an aerial bombardment; the Spirit of Tampa will rise in a mighty demonstration to show that this city celebrates the accomplishments of the New Deal and welcomes the dawn of an era of better times ahead. Tuesday at nine a.m. will see the start of an extensive drive to recruit an army of buyers who will assure a victorious followship to the demonstration of happy days.”

From the Tampa Daily Times, March 26, 1934: “The idea of the parade is to aid the return of better times and to rout the spirit of pessimism. The American Oil Company financed the expenses of the happy march as an investment in the general prosperity of the West Coast.”

From the Tampa Daily Times, March 26, 1934: “List of Prizes for the Better Times Parade: Girl with the biggest smile, $10; Man with the biggest smile, $10; Fancy costumes, first award, $10; second, $5; Funny costumes, ditto. Oldest and oddest auto, $10; Float depicting better times–Franklin D. Roosevelt trophy. Best appearing band-Better Times Trophy. Best appearing Drum and Bugle Corps–Happy Days Trophy. Best appearing ladies’ marching group–West Coast Trophy. Finest appearing drill team–Spirit of the West Coast Trophy. Firm having the greatest number of employees in line–Live Wire Trophy.”

IV.

AT NIGHT there was a meeting of Ybor City’s leading militants, some Communists, others sympathizers. The revolutionary movement is virtually illegal in Tampa, and the meeting had to be held in a private home. The workers walked up the dimly lit stairs in silence, singly, in twos.

Gomez, sitting at the head of a long table covered with white oil-cloth, was chairman. Men, women, young people crowded the big room facing the yard, and the smaller room beyond it facing the street. Mother Gomez sat in the front row, smiling thru her glasses; Yorkina sat with her elbows on the far edge of the speaker’s table, facing the chairman. In the last row of the front room sat Mama Romero, Vesper on one side of her, Vladimir on the other. Vladimir was standing up, waiting for the meeting to begin. He kills time by throwing shadows on the wall with his hands; it takes him ten minutes to make a rabbit. When his mother, exhausted by the day’s trials, leans over burying her head in her hands, he strokes her back gently; he loves her very much.

The Will To Fight

All the chairs are filled; around the walls workers stand closely packed together; in the back room, courteously giving place to their elders, stand members of the Young Communist League. Most of the audience are men; all of them Latin-Americans. Their dark faces are handsome, underfed, alert with the will to understand, to fight. “Comrades,” Gomez says in Spanish, “we have some visitors from the north who will speak to us later. But they have requested that first we tell them something about conditions in Tampa. I will ask you therefore to speak on conditions in cigar factories. You may talk in Spanish which they understand and which is easier for you.”

ONE after the other, men and women stand up in various parts of the house and speak with that extraordinary passion and eloquence so common among Latin American workers; their language is dramatic, direct, rhythmic; in terms of the most basic necessities and struggles they paint the life of proletarian Tampa:

The terror is growing; unemployed workers are literally starving, employed workers get wages on which it is impossible to live humanly. The Chamber of Commerce, the manufacturers have demanded that the workers accept further wage cuts. Every means is used to crush protest and organization; the blacklist marks every worker who is known to be active in the revolutionary movement. The bosses’ slogan is: no work for Reds. Stoolpigeons in the pay of the cigar manufacturers hang around the workers’ center trying to demoralize the workers, playing on their fear of starvation for their children, urging them to accept further wage cuts. The police has broken up so many meetings, arrested, jailed and deported so many comrades that the workers are forced to meet in secret. In this period of machine-gun rule, the A.F. of L. has betrayed the workers again, signing a pact with the bosses that no strike shall be called in the next three years.

Describe Abuses

One worker says: formerly, in the boom period, I made $40 a week. Here is my pay envelope for this week: $10.50…And I am lucky because I am a specially fast worker and we all get piecework rates. Most cigar workers today make between $5 and $8 a week.

Other abuses are described: since the industry started in Cuba, it has been the custom for workers to receive an allowance of five cigars a day which they roll for themselves. The allowance has now been cut to three. If you make more for yourself, you are fired; you may even be arrested. Women are not allowed to smoke at all in the factories…More important, the readers, abolished in 1931, have not yet been restored.

IN THE back of the room a young blond worker rises: “Comrades, nothing has been said so far about the conditions of the youth. We young workers growing up in the period of the crisis have no chance to learn a trade. We are not allowed to work in the big factories, only in the small sweatshops, and all we can make is 10 cents for a hundred cigars–that is, 10 to 20 cents a day. And we must pay for learning the trade; and like the older workers we must pay the foreman part of our wages in order to keep our jobs–you know, the kick-back. But the youth wants to organize; we will not let ourselves be terrorized; we will build a mighty organization of workers capable of leading us to victory.”

Another young worker, who, like most of the others, wears no tie, has his collar wide open at the throat, says: “Comrades, we have had reports only about the cigar industry. I want to say a few words about the citrus industry, started here recently, the factories where they can and pack citrus fruits. The girls there get only 10 cents an hour. They work standing on wet floors; the juice runs down on the floor, they get wet feet and fall sick; and when they are laid up they get no pay.”

Near the speakers’ table a swarthy worker stands up: “Comrades, we ought to have a report on the discrimination against Negroes in the tobacco factories. The Negroes, especially those from Cuba, know cigarmaking as well, sometimes better, than the white workers; but they are systematically excluded from Tampa factories.”

A short, stocky man, ruddy-faced, bald headed, gets up in back of the room. He is smaller but looks remarkably like the farmer from the palmetto section whom we heard at a meeting in Miami. “Comrades,” he says, “I am a farmer from Ruskin, where they have a lot of truck farms. The white farmers are getting sore about conditions. Every day you can hear conversations among them something like this: A farmer stands besides a heap of vegetables, unsold. He says: ‘Where is the market?’ Another farmer says: “The market has passed.’

“What am I going to do with all this stuff if I can’t sell it?’

“‘Eat it.’

“How can I eat all this?’

“I don’t know, but you voted for all this, didn’t you?’

“Comrades, I am myself a northerner, from the middlewest; but I have lived and farmed in Florida 28 years, and I know that the biggest problem here is the Negro problem. It’s hard for northerners to understand that, I sometimes think, as hard as it is for them to pronounce Tuesday the way a southerner does. But our chief job is to organize black and white; in order to fight capitalism we’ve got to overcome race prejudice.”

“The way to overcome race prejudice,” Gomez interjects from the chair, “is not to make abstract speeches about it either to Negro or white. We can unite workers of both races on the basis of concrete struggle. Black and white workers will unite when they have a common fight; and that common fight is the fight for better wages, hours, living conditions.”

An organizer sums up; he urges the workers not to be disheartened by the terror, by the loss of last year’s strike; he reminds them that the methods of capitalism in Tampa are the methods of capitalism everywhere

Germany, Japan, Poland, Latin America, China, Chicago, New York, Detroit, Pittsburgh. The revolutionary movement of Tampa is part of the world revolutionary movement; the Tampa workers must take courage from the heroic struggles of their comrades in these other countries, these other American cities…He contrasts conditions in Tampa tobacco factories with those in Soviet tobacco factories which he has visited and reminds them of the importance of the U.S.S.R. to the workers of the entire world.

Terror must be offset by proper organization, mass organization; they must build a new union, profiting by the mistakes of the last one; they must develop a local defense organization, an I.L.D. branch, which will make it easier to carry on the struggle; they must circulate the Daily Worker and other revolutionary publications among the workers, and must get out a local paper, even if it is only mimeographed. They must start study groups, possibly a school where local leaders may be trained in the theory and practice of the class struggle, where open forums may attract workers to the movement. The solidarity of the working class, led by the Communist Party, is the true road to victory.

There is no applause; this speech, like all the others, ends in silence. Applause would attract the attention of the police to the meeting. At the close, comrades shake each others’ hands hasta la vista hasta luego. They go down the stairs in silence, singly or in twos…

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1934/v11-n112-may-10-1934-DW-LOC.pdf