Benjamin Glassberg was a pioneer in teachers’ unionism, a history teacher at New York’s public schools until his dismissal in 1919. A founder of the Teacher’s League in 1913, explained below, Glassberg was one of five charter members of Local 5, Teachers Union, American Federation of Teachers in 1919. After his firing he worked for the Labor Research Department of the Rand School and edited the American Labor Yearbook.

‘The Teachers’ League: A New Movement’ by Benjamin Glassberg from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 14. April 5, 1913.

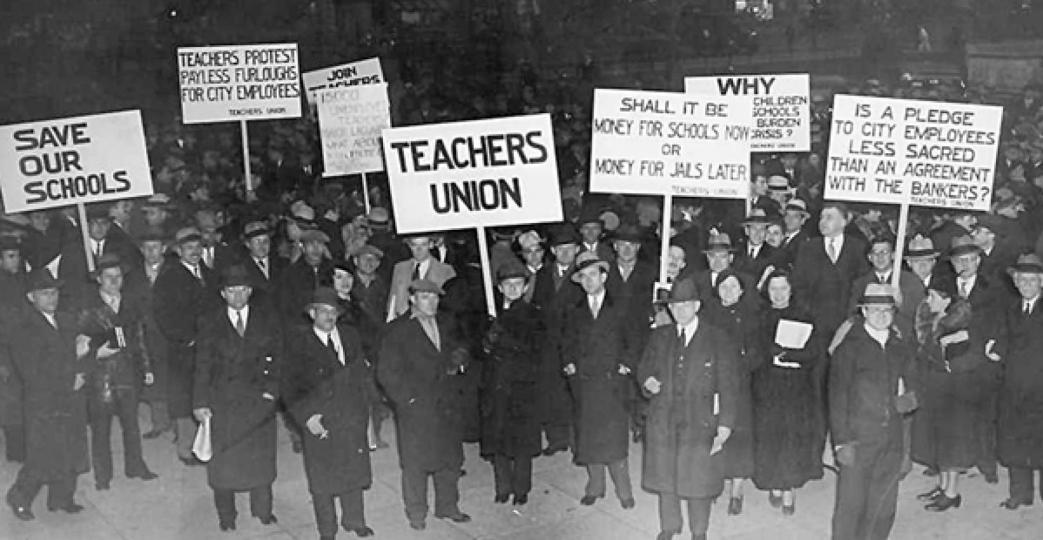

Many and various are the associations of teachers, but their purpose heretofore has been only one—salary protection. On February 28, 1913, the Teachers’ League was organized in New York. Now, for the first time the purpose is the protection of the cause of education, the school, and the rights of teachers.

Systematization and standardization, these two evil genii of large institutions, have reduced the teaching force of New York City to the level of automata. Thinking, on the part of teachers, is looked upon with decided disfavor. Uniformity is the ideal

To obey without questioning is one of the chief requisites of the teacher. Pupils may question and even disobey with impunity, but teachers must not question.

Our schools are supposed to turn out strong, self-reliant, thinking boys and girls. And this is expected to be accomplished by teachers who must repress whatever initiative or ideas they may have possessed when they entered the system, by teachers who find it to their advantage to flatter their supervisors, whose every act and movement is marked out and limited by a principal.

Is it any wonder that no such boys and girls are turned out?

Through their unions craftsmen have a voice in determining the conditions under which they shall work—the hours of employment, the rate of wages, the hygienic conditions of the factory, and the kind and amount of work they shall do. But the teacher who performs what is universally acknowledged as the most important function of society—the training of those who will be the fathers and mothers of the nation, who deals with human beings during the period when they are most susceptible to external influence, has no such privilege. He must teach his pupils according to a syllabus and methods that are determined for him. Throughout the city, the same subject matter, in the same amount, at the same time, and in the same manner must be taught, whether the children come from the

East or the West Side, whether they are immigrants or native-born, with absolutely no regard to difference in the condition, environment or experience of the pupils, and without giving the teachers the right to modify the syllabus to the needs of the pupils. And so we have the anomaly of one course of study and one syllabus for a city with the most cosmopolitan population in the world, with all possible varieties of economic and social conditions.

A French Minister of Education is credited with having said, “I can tell what is being taught in any school of France at any moment of the day.” We may boast of the same proud distinction.

What a comfort it is to turn to the methods adopted by the London schools. We find the following among the regulations:

“The only uniformity of practice that the Board of Education desires to see is that each teacher shall think for himself, and work out for himself such methods of teaching as may employ his powers to the best advantage and be best suited to the particular needs and conditions of the school. Uniformity in detail of practice is not desirable even if it were attainable. No teacher can teach successfully on principles in which he does not believe.”

What rank heresy this would be if uttered by a New York City teacher. To fight for such privileges the Teachers’ League has been organized. In the call issued for the organization meeting the following demands were made: “Teachers should have a voice and vote in the determination of educational policies; teachers should have seats in the Board of Education, with the right to vote; teachers should have a share in the administration of the affairs of their own school as the only practicable way for the preparation of teachers for training children for citizenship in a democracy; there should be serious study of the problems of the size of schools, size of classes, salaries and rating of teachers.”

Such in brief are the most important items in the program of this new league. Such as it is, it is the most radical movement ever begun among teachers in the East. For the first time some among the 17,000 teachers of the city have decided to cease being dumb, driven cattle. For the first time teachers have begun to take an active interest in their rights, in spite of the advice of one District Superintendent of Schools to leave the question of rights to the Board of Education, and of another superintendent who advised the teachers not to unite against their employers.

Vigorous and determined agitation will undoubtedly result in securing these elementary rights. Thus an important step will be made towards the democratization of education, with the consequent increase in the social efficiency alike of teachers and of pupils.

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n14-apr-05-1913.pdf