An extensive report to the Sixth Congress from the Communist Party of Great Britain on the period that elapsed since the Fifth, which saw the British General Strike, the formation of the first Labour Government. Included are economic and political reports, surveys of political parties and union movements, and the work of the Party the campaigns of its 7, 377 then members.

‘Report of Great Britain’ from The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

ECONOMIC SITUATION.

THE economic situation in the period since the last World Congress has revealed more markedly than ever the decisive changes that are taking place in Britain’s economic position in relation to world economics. Britain’s economic superiority is admittedly lost, and the decline is reflected in the general state of industry in the country. The basic industries—coal, iron, steel and cotton—have shown a steady decline, and doubts are expressed even by the bourgeoisie as to whether these industries will ever again occupy their former place in world economy. On the other hand, there has been a rapid development in certain new industries, such as artificial silk and automobiles, as well as in the chemical and electrical engineering industries. Significant of the changing character of British industry is the large increase in the number of workers employed in industries like the distributive trades, furniture making and building, i.e., in trades ministering to direct consumption, and a large decrease in coal mining, ship-building, iron and steel and engineering.

The present state of the basic industries in Britain has prominently brought to the front the question of rationalisation as a means of arresting the decline, and this is being strongly advocated by the leading sections of the bourgeoisie as well as by the Labour leaders. Rationalisation already carried out in the chemical industry begins to be applied to engineering.

Technical backwardness in the old basic industries proves an obstacle to their rationalisation, which so far has only taken the form of serious attacks upon the conditions of the workers. Nevertheless, a step in the direction of rationalisation has been taken in the coal industry by the formation in Scotland, Wales, and in the Midlands of cartels, and a scheme was brought out in Manchester at the beginning of the year for combining a number of cotton mills under a single company which would reorganise production on more efficient lines. In close connection with the movement for rationalisation is the movement for so-called peace in industry, which is advocated by the General Council of the Trade Union Congress, and supported by the big bourgeoisie headed by Mond, the purpose of which is to prevent the workers’ resistance to rationalisation.

An important symptom of the changing character of British economy is the marked increase in the adverse balance of trade. Since 1924 imports have steadily increased, while exports have remained practically stationary.

In the beginning of this year a levelling tendency in imports and exports was observed, but it has yet to be seen whether this tendency will be maintained. These sustained and considerable adverse balances clearly indicate the extent to which Britain is becoming a rentier country living on returns from foreign investments, and this helps to explain the flourishing condition of the luxury trades in the face of the steady depression in the basic industry.

This is confirmed by the steady increase in the proportion of new capital investments that are invested abroad.

Even in regard to home investments, statistics since 1920 show that the proportion of new capital invested in real industrial undertakings is diminishing, while that invested in government and municipal securities, railways, financial enterprises, and other enterprises likes cinemas, breweries, etc., is increasing. In regard to foreign investments, an increasing share of the new capital is being invested in the colonies.

Looming large in the background of Britain’s struggle to maintain her economic position is her conflict, steadily becoming more distinct and acute, with the United States.

Wages, Cost of Living and Unemployment.

While miners’ wages have dropped catastrophically, wages in other industries, according to government and bourgeoisie economists’ statistics, have remained stationary in the period under review, ranging between the index number of 170 to 175 of pre-war. The cost of living according to the official index has fluctuated with a tendency to drop, and on February, 1928,stood at 166 of pre-war.

The actual earnings of a vast number of workers in Britain, owing to systematic short time and long spells of unemployment, are even below pre-war, and recent investigations of the coal mining industry have revealed that the conditions of the vast majority of the miners are really desperate.

From 1924 to 1926 unemployment steadily increased from 10.3 per cent. in 1924 (out of about 12 million persons insured) to 11.3 per cent. in 1925, and 12.5 per cent. in 1926 (not including miners on strike). The figures for 1927, however, showed a drop to 9.7 per cent., and there has been a steady drop in the weekly returns of the actual number of unemployed in the first three months of 1928 with another rise, however, in the last week of April. The percentage of unemployment, however, continues to range between 9.7 and 10.7 per cent.

POLITICAL SITUATION.

In the domain of politics the situation in Britain since the last Congress has been marked by reaction at home and imperialist aggression abroad.

The so-called Labour Government, under the premiership of Ramsay Macdonald, failing to cope with the rising tide of the Labour movement, was ignominiously thrown out, and it went down amidst the jeers of the very bourgeoisie whose interests it tried to serve. At the general elections, which took place at the end of 1924, the Conservative Party stampeded the electorate by means of the notorious Zinoviev Letter, and succeeded in getting itself returned to the House of Commons with an overwhelming majority.

The period has been marked by the most gigantic social conflicts in the modern history of Britain. For the first time in modern times the power of the ruling classes in Britain was challenged by the working class, and was saved primarily by the treachery of the ofticial Labour leaders. Following this betrayal the Baldwin Government found itself free to turn the counterattack upon the working class, and to pursue its policy of imperialist aggression abroad.

Foreign and Colonial Policy.

The external relations of Great Britain during the period since the Fifth Congress have been determined by the strenuous efforts of the British Government to maintain Britain’s place as the predominant power in world politics in which she is being Strongly attacked by powerful new rivals on the one hand, and by the growing revolt of the peoples under her subjection on the other.

The growing economic development of the British Dominions and their growing economic intercourse with countries outside of the British Empire are causing the restraints imposed upon them by the British connection to become irksome to them, and Great Britain is compelled to resort to skillful maneuvering in order to retain them within the economic orbit of the British Empire.

On the European Continent the policy of the British Government in this period has been to maneuver between the conflicting interests on the continent with the aim of forging a hostile ring (to include Germany and France) around the U.S.S.R. and to prepare the ground for an attack upon her. The first important step in this hostile policy was Locarno in 1925, the second was the rupture of relations with the U.S.S.R., and the third the Birkenhead conversations in Berlin in April, 1928.

In the colonial countries the British Government has been steadily working to tighten the clutches of British imperialism upon the countries it held previously, and to consolidate its position in the new so-called mandated territories. Under a thin cloak of treaties and Acts, which ostensibly grant independence and self-government to these subjected countries, the British Government is conducting a policy of practical annexation. The aim of British imperialism is to acquire undivided mastery of the whole territory from the Sahara to India. In China the revolutionary movement was precipitated by the shooting by the British authorities of unarmed students and workers in Shanghai and Canton, and was later followed by the landing of a large British force in China for the purpose of overawing and crushing the revolutionary movement.

Meanwhile the growing economic rivalry between Great Britain and the United States is being reflected in the domain of politics. After the debt settlement with United States and Britain’s return to the gold standard of currency, the British Government strove to throw off the restrains imposed by the Washington Conference. It made overtures for a renewal of close relations with Japan, and laid plans for naval construction unhampered by an agreement with America. Following the breakdown of the conference between the United States, Great Britain and Japan at Geneva last summer it has become clear that both countries have now entered into a race for armaments with an eye to the day when the United States will forcibly challenge Britain’s command of the seas.

Home Politics.

In the sphere of home politics the Baldwin Government has turned its attention to the Communist Party of Great Britain, rightly judging that it was the only active force in Britain rallying the workers for the fight against the bourgeoisie and their Labour lackeys. After the stage had been properly set by the passing of the anti-Communist resolution at the Liverpool Congress of the Labour Party, the Government in 1925 raided the headquarters of the party and arrested nearly all the members of the Executive Committee, and sentenced them to varying terms of imprisonment.

During the general strike in 1926, and throughout the whole course of the miners’ strike, the Government utilised its forces to intimidate the workers and crushed the strikes. Thousands of workers were arrested and imprisoned for their activities in the strikes.

Following the betrayal of the general strike and miners’ fight by the Labour leaders, the Baldwin Government directed its attacks upon the rights of the trade unions and upon the sources of public aid to which the workers resort in periods of distress. By this means it aimed at cutting away the material support which enabled the workers to maintain their class solidarity. The Government gave legislative sanction to the return to the eight-hour day. This was followed by the Trade Union Act, by which sympathetic strikes, or even the advocacy of such, became criminal offences, and which cuts at the financial basis of the Labour Party.

The Government has also reduced the scales of unemployed benefit, and, moreover, workers suffering from prolonged unemployment have been deprived of benefits altogether.

The Conservative Government has made attempts to perpetuate its reactionary rule by a proposal to reform the House of Lords, which, if carried, would have given that body power of veto over all legislation. The opposition to this measure, however, was too strong, even among the bourgeoisie, to permit the Government to proceed with it. The Government is now endeavouring to achieve the same object by a measure to extend the franchise to women under 30 years of age, on the assumption that the majority of women vote for the Conservative Party.

THE POLITICAL PARTIES.

The Conservative Party.

The apparent division of the party into a “die-hard” group, and a more moderate group, proves to be merely a division of Labour, and so far no differences, if they existed at all, have led to anything in the nature of a crisis in the party. The party continues to have solid support in the House of Commons and that of the agrarians and big financial and industrial capital. The farmers have on several occasions expressed their discontent with the Conservative Government owing to the, in their opinion, inadequate Government support and protection of the farming industry. But the main plea of economy urged by the Baldwin Government finds support among the petty bourgeoisie generally, and even among certain industrialists who formerly supported the Liberal Party, as, for example, the Lancashire cotton spinners, who are demanding still further reduction of expenditure on social services.

The Liberal Party.

The Liberal Party does not show strong signs of recovery from the collapse it suffered after the break-up of the coalition. Nor does it appear to have a wide social basis upon which it can rebuild its power. The big bourgeoisie have gone in with the Conservative Party. The rift between the Grey and Runciman group, representing the traditional Liberal, commercial and industrial groups, on the one hand, and the Lloyd George group on the other, has not been healed. But Lloyd George controls the funds of the party, and therefore controls the party itself.

Under Lloyd George’s leadership the party is to make a big bid for the working class and petty bourgeois vote at the next election. The Liberal Party has advanced new proposals of land and industrial reform. The agrarian proposals are for the increase of taxation of land values, to give powers to local authorities to purchase land, encouragement to small farmers in the way of credit for the purchase of land and implements, etc. The industrial proposals are for the reorganisation of industry under State control, workers’ participation in management, minimum living wage, State acquisition of mining royalties, transference of a large proportion of local taxation to the State, etc. At the Convention of the Liberal Party, held at the end of March, this programme was accepted with slight amendment.

The Labour Party.

While in office the Labour Party proved itself to be no less ready to utilise the forces of the State against the workers than the bourgeois parties, and avowedly adopted the principles of “continuity” in its foreign and colonial policy. It mobilised the forces of the State against the transport workers in anticipation of the strike that threatened in 1924. It exercised the Emergency Powers Act at the time of the underground railway strike in London in the same year. Ramsay MacDonald heralded his entry into office by threats against the Indian national movement, and his Government endorsed the repressive Bombay ordinances under which the Labour and Nationalist movement was violently suppressed in Bombay. MacDonald gave utterance to strong words and even threats to Egypt after the breakdown of his negotiations with Zaghlul Pasha in 1924. Actually, military operations and the bombardment of villages from the air in Iraq were carried out in the period of office of the Labour Government. The Labour Government fostered and carried through the Dawes Plan for the enslavement of the German workers.

The defeat of the Labour Government was no less discreditable than its period of office. During the negotiations for a Trading Agreement with the U.S.S.R. the Labour Government was helplessly buffeted, first to one side—towards an agreement— by the pressure of the masses of the workers, and then to the other—against an agreement—by the pressure of capitalist interests. In the course of three days negotiations with the U.S.S.R. were first broken off, then renewed, and finally an agreement was signed. The bourgeois parties, upon whose votes the Labour Government depended, decided that they had no further use for it. Their opportunity came when, with its habitual vacillation, the Labour Government first instituted proceedings for sedition against R. Campbell, the editor of the “Workers’ Weekly,” and then, owing to the protests of the masses of the workers, dropped the prosecution. Using this as a pretext, they turned the Labour Government out of office in October, 1924. But the crowning shame of the Labour Government, headed by Ramsay MacDonald, was its action in connection with the forged Zinoviev Letter.

As his majesty’s opposition, the Labour Party throughout this period has acted in a manner calculated to paralyse every protest on the part of the masses, and by its sham opposition has acted as a shield of the bourgeoisie. It helped to betray the general strike, and throughout the whole period of the miners’ strike it strove to break the morale of the miners by continually urging them to accept the offer of the employers. Its opposition to the miners’ eight-hour day was farcical. It practically urged the workers to reconcile themselves to the Trade Union Act on the plea that they would come back to power at the next election and repeal it. It helped to create a favourable atmosphere for the despatch of troops to China. Its representative on the Blanesborough Commission signed the recommendation to reduce unemployed pay, but the E.C. of the party did not reprimand her for doing so. It supported the appointment of the Simon Commission on India, and appointed its own representatives to it, notwithstanding the protests of the Indian people against it.

The party leadership as a whole has swung still more to the Right than it was at the time of the Fifth Congress. The pseudo-Left wing led by Lansbury, Purcell and the rest, that emerged prior to the big strike movements, has sunk back into the fold of the Right wing, and has completely merged itself with it.

The Labour Party has thrown overboard the Socialist programme it adopted in the period of the rise of the revolutionary movement in England, and has now even abandoned its postwar demands.

Simultaneously with its policy of alliance with the bourgeois parties, the Labour Party leadership is conducting a ruthless campaign against the radical rank and file of the party.

In all respects the Labour Party is changing rapidly from its previous form of a loose organisation of affiliated bodies allowing the free expression of various views into a regular political party relying mainly on an active individual membership recruited largely from among the intellectuals and the petty bourgeoisie—and from bourgeois deserters from the Liberal camp—with a strong party discipline, relying upon the affiliated trade union membership merely as a base for its financial support. These are the circumstances which have made necessary a change in the attitude of the Communist Party towards the Labour Party.

Independent Labour Party.

The Independent Labour Party finds itself between the hammer of the Communist Party and the growing Left wing and the anvil of the Labour Party. Its former leaders, Snowden, MacDonald and others, have become merged with the reactionary Right wing of the Labour Party leadership, and consequently it has lost its former influence in the Labour Party. Indeed, it is now itself being subjected to attack. At the Blackpool Congress of the Labour Party, the I.L.P. was threatened if it dared to put itself in opposition to the Labour Party policy. Bowing to these threats, the party withdrew the half a-dozen or so “Socialist” resolutions standing on the agenda in its name.

The party has abandoned its “Socialism in Our Time” slogan, and substituted it by the slogan of the “Living Wage.” But even this has now sunk into oblivion. The party repeatedly rejected the offers of the Communist Party to participate in joint campaign in connection with urgent matters like the armed intervention in China and the Trade Union Act, and confined itself to mild verbal protest. It was very strong, however, in its denunciation of the Soviet Government for executing the 20 White Guards and hailed as a “striking victory for Socialism” Pilsudski’s successes at the last general election in Poland.

The Independent Labour Party tries to play the role of conciliator between the various wings of the Socialist movement, and at the beginning of this year issued a manifesto to the Socialist Parties of all countries appealing for unity between the Communist International and the Second International, and also for international trade union unity. This manifesto called forth a telling rejoinder from the Communist Party of Great Britain.

There is a growing section in the party that is dissatisfied with its policy, and the number of workers that have passed from the I.L.P. to the Communist Party is symptomatic of this. Particularly is this the case among the younger members of the organisation, a large section of whom have established close organisational contact with the Young Communist League. At the I.L.P. Conference held last Easter it was reported that last year the party lost no less than 249 whole branches. It is becoming evident to the working class members of the I.L.P. that in this period of acute conflict between labour and capital there is no room for a “centrist” party.

THE TRADE UNION MOVEMENT.

Although considerably weakened as the result of a huge loss in membership, unemployment, etc., symptoms were observed early in 1924 that the trade unions were pushing forward to resist the capitalist offensive. The strike wave of 1924, the setting up of the Anglo-Russian Committee, the emergence of the so-called “Leftists” (Purcell, Hicks, Bramley) on the General Council of the Trade Union Congress, and the launching of a National Minority Movement in the same year were positive signs of the Leftward swing of the masses.

When Baldwin gave the signal for the general capitalist offensive in 1925—”The wages of all workers must come down”—the rank and file of the trade union movement rallied to the counter-attack and expressed their militancy in the united front of July, 1925, which culminated in “Red Friday,” when the General Council was compelled by the direct pressure of the masses of the proletariat to threaten a general stoppage.

This rising tide of mass militancy was confirmed at the Scarborough Trade Union Congress in 1925, at which resolutions were passed which, if honestly adopted and carried out by the leadership, would have brought about fundamental changes in the British trade union movement.

But already at that time the treacherous designs of the official trade union leadership were beginning to reveal themselves. While talking glibly about the necessity for improving the state of organisation of the working class the trade union leaders did not do a single practical thing to organise the workers for resistance to the capitalist offensive. When the test came with the General Strike of May, 1926, the trade union leadership openly adopted a defeatist policy. The so-called Left wing utterly collapsed and fell in with the policy of the Rights.

At the very time when the strike movement was in full swing, when the workers were displaying a solidarity and militancy hitherto unprecedented, the General Council, to the astonishment and dismay of the masses of the workers, informed the Prime Minister that “the General Strike was being terminated to-day (May 12th).”

The Miners’ Federation refused to agree to a settlement on the terms then proposed, and the miners continued the fight alone. But the General Council did all they could to hamper the miners in their unequal struggle. It turned down the demand for an embargo on coal, and also rejected the proposal for a levy on the whole trade union membership in aid of the miners’ strike funds.

Characteristic of the attitude of the official leadership was their contemptuous rejection of the generous aid offered by the masses of the Russian workers to the British workers at the time of the General Strike, and their complaint, like that of the British Government, that the aid rendered to the miners was “interference in British affairs.”

The low-water mark of the bankruptcy of the trade union leadership was indicated, first at the Conference of Executives and then at the Edinburgh Trade Union Congress last year. This Congress registered the complete swing over of the official leadership towards reaction. This was expressed in the resolutions passed at the Congress, the principal of which may be summarised as follows: (1) Capitulation on the question of the Trade Union Act; (2) break-up of the Anglo-Russian Committee—which, in fact, had been sabotaged by the General Council all the time it existed; (3) refusal to deal with the scabbing tactics of Havelock Wilson, the leader of the Seamen’s Company Union; (4) declaration in favour of “Peace in industry”; (5) the declaration of war on the minority movement.

The demoralisation resulting from the defeat created certain favourable grounds for the spread of a scab union movement, led by the renegade Spencer, but the trade union officials took no measures whatever to counteract it. It refused even to take disciplinary measures against Havelock Wilson, who granted a considerable sum of money out of the Seamen’s Union funds in aid of Spencer scab unionism. In the Nottinghamshire coalfields the employers refused to deal with the official Miners’ Union and would agree to recognise only the Spencer Union. They went even further, and attempted to compel the miners to leave the Miners’ Union and join the Spencer Union. The General Council made a great display of energy, and intervened in the case, first of all demanding that all criticism of its actions by the Miners’ Union must cease.

This pompous blackmailing intervention took the form of a proposal to take a ballot of the miners on the question as to which union they desired to belong. The ballot was taken in the early part of May, and resulted in an overwhelming vote in favour of the Miners’ Union—32,277 for the Miners’ Union and only 2,533 for the Spencer Union. The vote showed that scab unionism could be easily crushed if the trade union officials gave a proper lead to the workers.

THE MINORITY AND LEFT WING MOVEMENTS.

The Minority Movement.

The National Minority Movement came into existence in 1924, and since then has made considerable progress. It is now recognised as the organised opposition to the existing trade union leadership, and as such has all the guns of the trade union bureaucracy turned against it.

The following table shows the growth of the movement as expressed in the number of delegates attending the various annual conferences held since its formation and the number of organised workers represented:

The minority movement, guided by the Communist Party, played an extremely important part in the preparations for and the conduct of the General Strike. It convened the first great rank and file assembly; the Special Conference of Action, convened in March, 1926, which denounced the findings of the Samuel Commission on the mining industry and formulated a counter-plan of action. In this, however, it displayed a certain inconsistency, for, while in itself it was an organised protest against the defeatist policy of the General Council and was one of the principal instruments for exposing this policy, it nevertheless issued the slogan of concentrating the leadership of all the unions in the General Council. However, the other items in its plan of action contributed enormously to rallying the workers in the strike and maintaining their militant spirit. These items were: (1) Election of factory, shop and pit committees; (2) concerted action between the trade unions and the co-operative societies; (3) creation of a Labour Defence Corps; (4) propaganda among the forces; (5) agitation for the repeal of the anti-Labour and sedition laws. It is no exaggeration to say that the fine fighting spirit of the masses of the workers in the localities during the general strike was due to the efforts of the minority movement under the political leadership of the Communist Party.

On the betrayal of the strike by the officials the minority movement agitated for an embargo on the export of coal and a levy on the trade union membership in support of the miners’ strike funds.

By 1927 the minority movement had become a serious menace to the trade union bureacracy. That they realised this is evident by the statement made by A. Conley, a member of the General Council, at the Bournemouth Trade Union Congress in 1926 in opposing the affiliation of Trades Councils which supported the minority movement that: “If the Council had agreed to this affiliation, within a short time the minority movement would become the majority.”

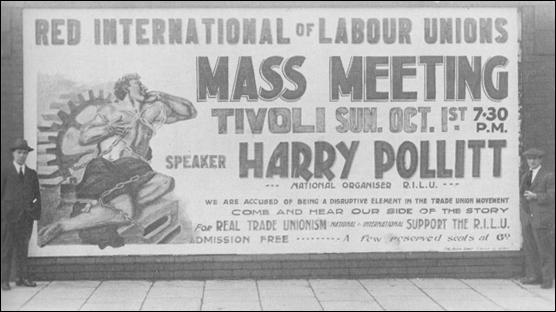

Notwithstanding these attacks the minority movement is making headway in the general trade union movement, and has succeeded in capturing a number of positions on the leading bodies of various trade unions as well as in the local organisations. In this respect the minority movement is particularly successful in the Miners’ Union in Scotland, where it now has a majority on the Scottish Mine Workers’ Union as well as on the executives of the Fifeshire and Lanarkshire Miners’ Unions. Comrade Horner is on the Executive Committee of the South Wales Miners’ Federation and of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain. Comrade Pollitt, for several years in succession, has been elected delegate to Labour Party Congresses by the Boilermakers’ Union. In the recent elections for the general secretaryship of the Engineers’ Union, Comrade Tanner opposed the present secretary, Brownlie, and received 13,476 votes, which represented over 50 per cent. of the votes obtained by Brownlie.

Left Wing Movement in the Labour Party.

The discontent with the defeatist policy of the official leadership in the Labour Party has found expression in the formation of a Left wing in that organisation, which first sprang from the Liverpool exclusionist decisions in 1925, and took organisational shape in 1926, and now has groups throughout the country. The Left wing works in close contact with the Communist Party, and its policy is largely guided by the latter. At the inaugural conference it was reported that 65 groups had been established: 2 in London, 6 in South Wales, 5 in Lancashire, 9 in Yorkshire, 11 in Scotland, 4 in the Midlands, 3 in naval ports, and the remainder in other parts of the country. At the conference 145 delegates were present. The conference discussed the Liverpool decisions of the Labour Party concerning the expulsion of Communists and disaffiliation of organisations refusing to abide by the Labour Party Executive decisions, and preparations were made to put up a fight against these decisions at the ensuing Labour Party Congress in Margate. As a result a strong Left wing fraction consisting of 60 delegates was formed at the Margate conference, which came out in an organised manner against the official policy.

Considerable organisational progress was reported at the Second Left Wing Conference held in September, 1927. At this conference 54 local Labour Parties and groups, aggregating 150,000 individual members, were represented.

By this time also the campaign against the Left wing movement in the Labour Party had been intensified, with the result that at the last conference of the Left wing movement the disaffiliation of 28 local Labour Parties was reported: 19 in London, 5 in South Wales, 2 in Scotland, and 2 in the North of England.

The disaffiliated local Labour Parties continue to function as independent bodies in their localities, in close contact with the Communist Party. At recent local elections the disaffiliated parties have put up candidates in conjunction with the Communist Party against the official Labour candidates with a fair amount of success. Preparations are also being made to put up candidates for the forthcoming Parliamentary elections.

THE COMMUNIST PARTY.

In the period under review the Communist Party of Great Britain has emerged as one of the important factors in British politics generally, and in the Labour movement in particular.

It has not yet succeeded in becoming a mass party from the point of view of numbers, but through its leadership of the minority movement and Left wing movement the party exercises direct influence upon masses of militant workers far exceeding its own numerical strength.

The party has been fighting on numerous fronts under the direct blows of the Government. In the course of their activities during working class struggles thousands of the members of the party, including members of the E.C., have been subject to arrest and imprisonment. Notwithstanding this the party has continued the struggle, and is winning increasing support among the militant sections of the Labour movement.

The party and the Comintern suffered a sad loss by the death of Comrade Arthur MacManus in March, 1927. Comrade MacManus was one of the founders of the party, its first chairman, and also a member of the E.C.C.I. During his comparatively short life he played an active and leading part in the revolutionary Labour movement. From the time when, in 1916. he was deported as a leader of the shop stewards’ movement, up to his imprisonment in 1925-26 by the British Government as one of the twelve Communist leaders, he was in the forefront of party activities. Almost his last activity was to participate, on behalf of the party, in the foundation of the League Against Imperialism at the Brussels Conference in February.

In the main, the party has been able to maintain the unity of its ranks, and while differences of opinion have naturally arisen from time to time on the leading bodies and in the local organisations this has never affected the close co-operation of all units of the party. It must be stated that the party is entirely free from Trotskyist or any other reformist elements.

The Party Policy.

Engaged as it has been in strenuous struggles and tasks of a proportion far in excess of its numerical strength and resources the party has not always been able to see the struggle in its true perspective, and has not been able on all occasions to manceuvre with sufficient flexibility in the midst of changing circumstances. Throughout this strenuous period the party has adopted a sharp line of criticism and of exposure towards the Labour bureacracy, but the effect of this line was diminished to some extent by its weak conduct of the campaign for a change of leadership. This line was marked during the General Strike, and recurred again in 1927 in the resolutions of the Party Congress and in public statements concerning the anticipated coming into office of a Labour Government after the next general election. The party was slow also in reacting to the changed situation created by the sharp differentiation in the Labour movement caused by the decisive turn to the Right of the Labour bureaucracy and the steady swing to the Left of the masses. The tremendous issues involved in the struggle in Great Britain have caused the Comintern to follow the development of events there very closely, and by maintaining constant contact with the British Party has helped it to straighten out its line when it erred.

The New Tactic.

The party executive itself realised that the events of the past two years made it necessary to take stock of the situation and define anew its attitude towards the Labour Party. This it did in an open letter to the party membership, published in the “Worker’s Life” in January last, in which, while noting the definitely reactionary policy of the Labour Party and the swing to the Left of the masses of the workers, declared that criticism of the Labour bureaucracy must be sharpened, but that the time has not come for altering the policy of continuing the fight against the bureaucracy within the framework of tie Labour Party.

Moreover, at the Ninth Congress of the Party a resolution was passed stating that “the fight for a Labour Government is the main task.” The tactics of the British Party in the present period served as one of the principal items of discussion.at the Ninth Plenum of the E.C.C.I., to which the majority of the E.C. of the British Party submitted a thesis embodying the lines enunciated in the open letter. After a thorough discussion of the subject the Ninth Plenum on February 18th this year resolved unanimously—including the British Delegation as a whole, that the change in the situation in Great Britain necessitated a departure from the advice given by Lenin to the British Party in regard to the Labour Party, and that the time had come when the Communist Party of Great Britain must come out openly as the sole political party of the working class opposed to the Labour Party, which has become Social-Democratic in form and bourgeois in character. This line was to find practical expression among other things in the party independently putting up its own candidates for public bodies, and particularly for Parliament, in the forthcoming general election, even in constituencies contested by official Labour candidates, and especially in these constituencies represented by the prominent Labour leaders.

The decision of the Ninth Plenum was discussed at the full meeting of the E.C. of the British Party in March, and carried unanimously. It was also submitted for wide discussion to the rank and file of the membership of the party, and was adopted almost unanimously—a small minority, while agreeing with the general line, insisted upon the abandonment of further demands for affiliation, which had not been decided upon at the Ninth Plenum of the E.C.C.I.

The Party and the Strike Movement.

The party was particularly active in the General Strike and in the Miners’ Strike, and the influence it exercised upon the masses in these struggles proved its fitness to act as the leader of the working class. It was the only party that, during the nine months’ truce between July, 1925, and May, 1926, prepared the workers for the impending fight.

The party initiated and was the leading spirit in the preparations made by the rank and file for the strikes, the formation of the committees of action, local strike committees, etc. The party members were active on all the local strike committees. Through its regular organs as well as through a “Special Bulletin,” which was sent to the districts, there to be duplicated and distributed broadcast, as well as in special literature, the party urged the workers to stand firm in the struggle, warned them against the probable betrayal by the leaders, and strove to give the strike a political turn by issuing the slogan, “Down with the Baldwin Government.”

With the collapse of the General Strike, the party concentrated its forces in the mining districts. Here, too, the party members were active on local committees and among the masses of the miners rallying them to resist the attempts of the trade union bureaucracy to compromise on wages and hours, organising relief for the strikers and rallying the rest of the workers to come to their assistance. The party initiated the campaign for an embargo on the export of coal and for a levy on the trade union membership in aid of the miners’ strike funds.

As a result of these activities the party’s prestige has been raised enormously among the masses of the workers, particularly among the miners, and a large influx of miners as well as other workers into the party took place at that time.

The party has been active on other sections of the industrial field. It took an active part in the unofficial strike of the seamen in 1925, and close contact was maintained between the party’s industrial committee, and the seamen’s strike committee. In the early part of this year the party took a leading part in organising the resistance of the cotton textile workers to the employers’ attempts to reduce wages and increase hours, which resulted in the attempt being defeated. Even the capitalist press admitted that the good fight put up by the workers was due to the influence of the Communists.

The party is also conducting a wide campaign throughout the Labour movement against the General Council’s policy of industrial peace. In addition to participating in these great struggles, the party has initiated and conducted a number of important campaigns in connection with important issues that came up, of which the following ure the most outstanding:—

Hands Off China Campaign.

In addition to persistent propaganda and the distribution of a large quantity of literature dealing with this subject, the party initiated the Hands Off China Committee movement, and it is largely due to the party’s efforts that a wide campaign was conducted in the Labour movement throughout the country. The campaign resulted in the setting up of over 70 Hands Off China Committees in the country and the holding of numerous local conferences, and a large London conference attended by 587 delegates. The party organised the distribution of antiimperialist literature among the troops as they were being embarked for China, which had a marked effect upon the soldiers.

Anti-Trade Union Bill Campaign.

On the initiative of the party the May Day demonstration in 1927 was converted into a huge mass working class demonstration against the Baldwin Bill and against the sham opposition to the Bill by the labour bureaucracy. The party issued the slogan of the General Strike, and called for the establishment of factory committees and the convening of special conferences of trade unions in preparation for resisting the Government’s operation of the Act. However, the party revealed certain weakness in its campaign of exposing the sham opposition of the General Council to the Bill by failing to criticise the General Council with the sharpness demanded by the circumstances.

Rupture with Russia Campaign.

The party has all the time kept to the front the defence of Soviet Russia against the attacks of the Baldwin Government. On the rupture of relations with the U.S.S.R. the party immediately renewed the agitation for Hands Off Russia Committees, and this campaign was extended further, to include agitation for the establishment of councils of action in preparation for decisive action against the Baldwin Government’s preparations for war against the Soviet Union.

Sacco and Vanzetti Campaign.

A big campaign against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti was conducted in Great Britain under the auspices of the official Labour movement in which the Communist Party took an active part. The party, however, was practically alone in pointing out the skillful use to which British imperialism was putting the hostility roused to the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti in its own anti-American policy and in drawing attention to the acts of judicial murder of fighters for liberty in the British Empire.

Parliament and Elections.

The party has only one member in the present Parliament, Comrade Saklatvala, who has voiced the workers’ protest against the acts of oppression of the British Government, both at home and abroad, but not always in complete line with Communist policy.

A number of party members occupy seats on local government bodies in London and in the provinces. Since the Labour Party bureaucracy adopted the tactics of expelling Communists, the party has put up candidates for public bodies in conjunction with the disaffiliated local Labour Parties against official Labour Party candidates. This was practised in the London County Councils elections in March, 1927, when the Communist and Left wing polled a fair vote, and in one case polled a higher vote than the official Labour candidate. The elections to the local public bodies in the provinces in April showed better results, and in a number of cases our comrades were elected.

International and Colonial Work.

The party has kept the struggles of the workers and the oppressed peoples in the colonies well to the front in its press and general propaganda. It has kept contact with the Communist Parties in these countries, and has on various occasions sent its representatives to Ireland, China, India, Egypt and Palestine to obtain first-hand information and to render assistance.

The party was instrumental in getting a large delegation fully representative of the rank and file of the British Labour movement to visit Soviet Russia on the Tenth Anniversary of the October Revolution. On the return of the delegation to England an interesting report was published in two large editions. In addition, a number of other pamphlets were published dealing with special subjects concerning Soviet Russia. The delegates travelled over the country addressing large meetings of workers. A National Society of Friends of Soviet Russia was formed, and local branches were established in a large number of districts throughout the country. A national conference of local Friends of Soviet Russia Societies was called at the end of April.

Agitation and Propaganda Work.

The agitation and propaganda work of the party centre has been widely developed in the period under review, but proper organisation has not yet been achieved in the districts, and measures have been taken to remove this defect. The party centre now issues an Agitprop Bulletin containing information on the important campaigns that are conducted and material to aid the party agitators and propagandists in a closer study of the questions of the day.

A system of party training has been introduced, consisting of the following grades: (a) Elementary party training classes in the locals; (b) party workers’ classes in the districts; and (c) central party school. A party training manual has also been published, and, in addition, a “Self-study syllabus” is published monthly in the “Communist.”

The Agitprop Department regularly issues a political letter to all the locals and factory and pit groups, which serves as a basis for the discussion of important questions and as a useful means of party training.

The party press has had to meet enemy attacks in the form of libel actions in the courts. As a result of an unfavourable verdict the “Workers’ Weekly,” founded at the beginning of 1923, was compelled in 1927 to go into bankruptcy. The “Workers’ Life” has since been issued in its stead. The paper has been much improved in character, and consists usually of six pages, and on special occasions of eight pages. A regular feature of the paper is the “Miners’ Supplement.” The circulation of the paper is not as large as it should be. Lately the party has undertaken a campaign to enlarge the circulation of the paper with a fair amount of success. A gratifying feature of the paper is the fairly large corps of WORKER CORRESPONDENTS it has been able to establish, who provide valuable material directly from the factories in the localities.

The party has fairly well developed its publication work, particularly during the past two years. In this period it has published 28 hooks, including a number. by Lenin, Bukharin, Stalin, etc. The number of pamphlets published during this period was 41, in editions ranging from 5,000 to 35,000, covering a wide range of subjects. In addition to this, 67 leaflets, manifestos, etc., were published in editions ranging from 5,000 to 285,000, the latter figure being that of a manifesto on war.

Work in the Trade Unions.

The Industrial Committee of the party holds frequent consultations with party members holding responsible positions in the trade unions, discusses with them the affairs of the respective unions, and works out the lines of work to be conducted. A special feature of the work in the trade unions has been the drafting of programmes of action for various trades which now serve as the basis for rousing the trade union membership to fight against the inactivity of the leaders, and for intensifying the struggle against the capitalists. Such programmes have been drawn up for the builders, metal workers, vehicle workers (taxi-drivers), textile workers, railwaymen, etc.

The work of the party fractions within the leading bodies as well as in the local organisations of the trade unions has improved. Particularly is this the case with the work of the fractions at national conferences of the separate unions as well as at the Trade Union Congresses, at which the party fraction helps to organise the fractions of the minority movement and works with it.

The fraction work in the Trades Councils is also improving. At the second conference of the Trades Councils, two party members were elected to the Joint Consultative Committee of the Trades Councils and Trade Union Congress, nine party members were elected as delegates to the Trade Union Congress, and a number of resolutions suggested by the party were placed on the agenda of the Trade Union Congress.

A number of party members now hold prominent positions in various trade unions.

Work Among the Women.

Considerable progress has been made in the party’s work among women. This result has been largely achieved by the systematic work carried on by the women party members, especially in the women’s section of the Labour Party.

The party has also extensively developed the system of women delegate meetings and district conferences of women delegate meetings. These women delegates conferences have sent their representatives to all conferences called to discuss national issues, and have participated in campaigns initiated by the party.

Special work among women in the factories is not developed yet to the same extent, but the party’s activity in the recent disputes in the textile industry has helped to stimulate this work.

A tribute to the party’s work among women is the fact that International Women’s Day has now become an established festival in the British Labour movement. This year a huge demonstration of women was organised in Trafalgar Square, London, consisting, in addition to London working women, of numerous delegations of working women from the provinces, particularly from the mining and textile districts. Besides the London demonstration special women’s meetings were organised in numerous provincial towns.

A monthly women’s paper is published, which now has a circulation of about 4,500, and which is increasing. In addition special literature for women is published.

Work Among the Unemployed.

Notwithstanding the large army of unemployed and the attacks made by the Government upon the relief of unemployed workers, the unemployed movement as such has tended to drop into the background in the face of the big struggles that have taken place in the movement generally. Nevertheless, the party has carried on work in conjunction with the National Unemployed Workers’ Committee movement to organise the unemployed and to press forward their demands. An important feature of the party’s work in this sphere have been its efforts to get the unemployed movement recognised as an integral part of the general Labour movement, but so far this has been successfully sabotaged by the trade union leadership. Nevertheless, the organisations of the unemployed have obtained right of affiliation to a number of local organisations. Numerous demonstrations of unemployed have been organised in London and in the provincial towns, especially in connection with the Blanesborough report and the Local Authorities’ Act. The most striking of these was the organisation of the miners’ march from South Wales to London, which was carried out in spite of the sabotage of the Labour bureaucracy, both in the centre and in the localities.

Work in the Co-operatives.

The party’s work in the co-operative movement still lacks development, although greater attention is now being devoted to it.

During the strikes in 1926 the party initiated the campaign in favour of material aid being rendered by the co-operative societies to the workers on strike, and in many districts this was effected.

On the eve of the Congress of the Co-operative Union in Cheltenham, in May, 1927, the party published an open letter, explaining its attitude towards the co-operative movement, which was distributed to all the delegates at the Congress. The London party Committee also called a special conference to discuss work in the co-operative movement. This resulted in the work of the Communists and left wingers being better organised, and a small fraction was formed.

The party’s campaign for sending a delegation of co-operators to the U.S.S.R. on the Tenth Anniversary was successful. Several of the delegates joined the party.

Party Organisation.

It is to be regretted that the party has not managed to build up its organisation numerically, commensurate with its activities and the wide sphere of its influence. Moreover, the party has not yet acquired the organisational methods for retaining permanently the members that join the organisation. During the period under review the party membership has undergone considerable fluctuation. It had a large influx of members during the period of the big industrial struggles in 1926, but since then it has lost a considerable number of the new members. The fluctuation in membership is partly to be explained by the severe victimisation to which active workers in the Labour movement are being subjected at the present time, the brunt of which, of course, falls upon the members of the Communist party.

In 1924 the party membership numbered about 4,000, and the party was entirely organised on the basis of local groups. Since then the party has undergone re-organisation, and a portion of the membership, although not very large, is now organised on the basis of factory nuclei.

By April, 1926, the membership increased to 6,000, and there were already 161 nuclei, with an aggregate membership, however, of only 947. Between that period and September, 1926—the period of the General and the Miners’ Strike—the party had an influx of nearly 5,000 new members. Of the 10,730 members, 1,763 were then organised in 316 factory nuclei.

The great bulk of the new members were miners who came in under the influence of the militant spirit prevailing during a period of the industrial struggles, but the majority of whom drifted out of the party in the course of the next year.

By the beginning of 1927 the party membership had dropped to 9,000. Of these 1,315 were organised in 149 nuclei.

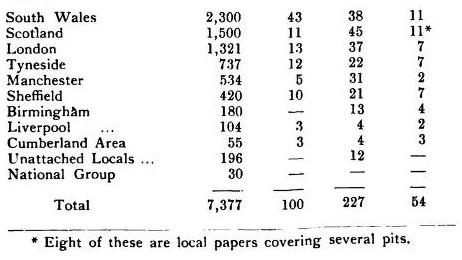

At the time of the Ninth Congress of the Party held in October, 1927, the membership of the Party, the form of organisation and the number of factory papers published was reported as follows:

The total number of women members ts approximately 1,700, of whom, however, only 272 are factory working women.

Of the total membership 5,800 belong to trade unions. Making allowances for those not eligible for trade union membership, the percentage of those unorganised in trade unions is still fairly large, i.e., about 15 per cent.

In regard to the activity of the Party membership, 1,455 members are active in local Labour Parties, 252 are delegates to local Labour Parties, and 690 are delegates to trades councils, 898 members are active individual members of the minority movement.

The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2.pdf