A veteran logger describes life and work in the woods, where there is zero romance in ‘simple living’.

‘The Life of a Lumberman’ by George Ward from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 1 No. 6. August, 1919.

(Card Number 245818)

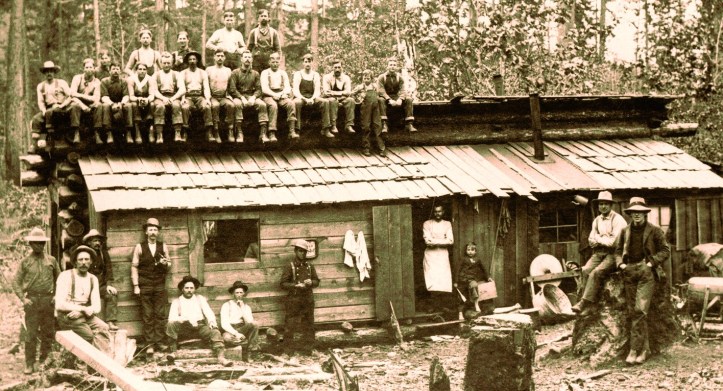

AT THE AGE of 18 in the year 1898 I landed in a lumber camp for the first time. That was in upper Michigan for Smith & Alger Lumber Co. Since that time I have visited several and have found them all pretty much alike. The wages at that time was from $20 to $35 per month and board. The board consisting of corned beef, commonly known as red horse, salt pork, beans, potatoes, bread and some pastry. This camp worked a crew of about 90 men, all sleeping in one bunk house. Double-decked board bunks that the Jacks called “muzzle loaders,” which means that the bunks are built along each side of the bunk house, spaced off to allowing 4 ft. 6 in. for two men. Of course, we had to sleep two in a bunk. One had to crawl in and lay with head to wall and feet toward main floor, which made it so dark one could not read without a light even in day time. In the center of the floor was a large stove to heat the building and also to dry the wet clothing including socks, which are wet every night. One can imagine how one would feel wakening up in the morning after inhaling such fumes all night.

In the fall of the year they cut the timber, skid it out to the sleigh road and decked it into large roll ways. At this time they would work the crews eleven hours per day. Then when winter set in and it got cold enough they make ice roads and start hauling the logs on sleighs to the landing on the river bank, where they are again decked in large rollways, until the spring freshets come, then they are rolled down to the mills which are built further down, close to a market where they are sawed into lumber.

When the sleigh haul started were the great days. The company always saw to it that they had a good live foreman, one who could “con” the men and keep them in good spirits and get the work out of them even to the extent of having a stool pigeon system organized among them carrying tales to him about one another. When the sleigh haul started, the only thought seemed to be to get the logs to the landing. The foreman would see to it that there was a rivalry started among the crew, which of course had the result of increasing the efficiency of the crew with no expense to the company. For instance, there was always a striving among the loaders to see which gang could put on the best load in the shortest time and also among the teamsters to see who could haul the most number of feet at a load and make the best time to the landing. Four-o’clock breakfast was the rule, and if a teamster was lucky he would get in at five or six o’clock in the afternoon; if unlucky, it might be nine or ten o’clock, with their horses to take care of after that. I have seen teamsters come in, pull off their rubbers and crawl into their bunk, clothes and all, catch three or four hours’ sleep, and up and at it again. For this they got the magnificent sum of $35 per month. No over time.

Then when the spring thaw came and the ice went out of the river, the drive started. The men would go out, break the rollways to roll the logs into the stream. The most experienced would go down-stream and wherever any logs would jam they would go out on them with peevies and break the jam. This is a very dangerous work, as all jams have what is called key logs, which get fouled on the rocks. The other logs keep piling upon them until huge tiers of them pile up, choking the stream from bank to bank and filling it up for some distance up-stream, causing the water to rise, therefore causing immense pressure. As the men have to work on the key logs, prying and working them loose, when the jam starts the whole seething mass comes pitching and tumbling forward, they have to make a quick get-away, and the least slip of the foot might mean death, being ground into a pulp among the logs.

Others stay behind to keep the logs all in deep enough water, so they will float. This means wading in ice cold water from knee-deep to arm pits, all day, from daybreak until dark. For this they receive $2.50 to $3 per day. The men get breakfast in camp. They each have a lunch sack which they load up to last them through the day, and they are lucky indeed if they manage to keep it dry until eating time. For supper in camp they some times have a hike of ten or twelve miles to camp. As a general thing their clothing is never dry from the time the drive starts until the finish, usually from twenty to sixty days.

The foreman is the big king pin in a logging camp. A logger goes out to camp, gets a job, is told what the pay will be. If he works a month and becomes dissatisfied and calls for his pay, and the foreman feels like it, he will pay him off at what they term “jumpers’ wages,” which is anything that he took a notion to give him. As there were no organizations among the men he would take it and go, as kicking would be useless. And as the foremen were usually big huskies and tough men, unless a man were a good scrapper, he would get beat up and kicked out of camp. But since the I.W.W. have been getting on the job and awaking the working slaves, conditions are getting better. The slaves see where there is strength and power in organization and instead of working for the masters’ interests, they are working for their own, making an injury to one an injury to all, shortening the work day, getting better conditions, and bringing the time closer when we shall do away with the wage system and produce for social use instead of the masters’ profits.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/one-big-union-monthly/v01n06-aug-1919_One%20Big%20Union.pdf