Tens of thousands of steel workers strike in Pittsburgh, igniting a labor rebellion in the city and a summer of intense class war.

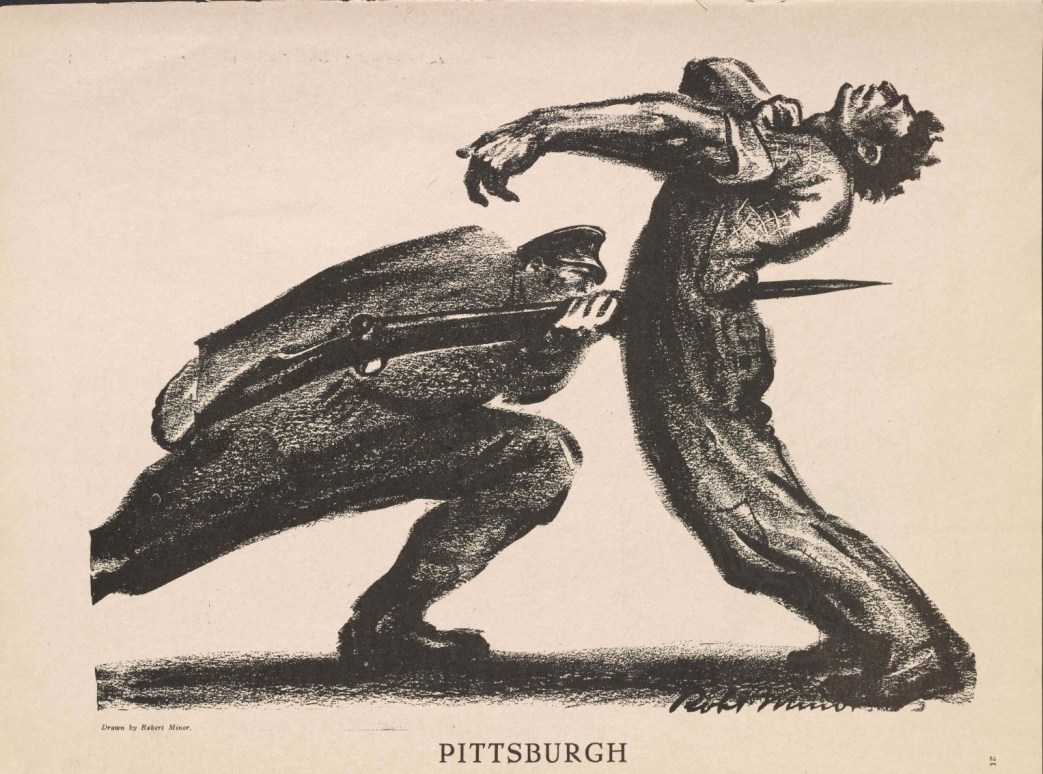

‘The Pittsburgh Strike’ by Dante Barton from The Masses. Vol. 8 No. 9. July, 1916.

WITH a beginning of 60,000 workers on strike for the eight-hour day in the Pittsburg district, Isaac W. Frank, multi-millionaire, president of several great machine works and head of the Employers’ Association of Pittsburg, told the writer of this article that Frank P. Walsh, Chairman of the Committee on Industrial Relations, “ought to be assassinated.”

He rested his violent frame of mind against the body of Frank Walsh on the assertion that Mr. Walsh, as Chairman of the United States Commission on Industrial Relations, had stimulated the demands for the eight-hour day and for better wages to workers and for collective bargaining by workers, and had “intimidated” the big employers of labor into admitting that those demands were right.

Isaac W. Frank, along with the other Pittsburg exploiters of labor, had seen the war profits of all of them dwindling, or ceasing altogether, because the workers had taken their opportunity to force good wages, to force shorter hours, to force their own control of their own lives.

The Steel Corporation, master of Pittsburg, master of the Employers’ Association, and master of Isaac W. Frank, had seen the strike spreading to its own great plants and threatening its own great profits. One million dollars profits a day the Steel Trust had made for nearly a year-and it saw the golden flood dammed by the simple process of those who poured it into their chests refusing longer to pour it.

Seeing those things had made the master Steel Trust and its associate masters mad with fright and mad with the rage of still unsatisfied greed. Something had to be done.

Something was done.

The Steel Corporation remembered that the Carnegie slaughter of the workers in Homestead in 1892 had kept its companies absolute masters of its men for a quarter of a century. It applied that lesson, called to its Edgar Thomson works in Braddock the Coal and Iron Guards of Gary–some of them Ludlow “veterans”–and shot round after round from riot guns into the crowds of men and women and children who were calling to their fellow workers to come out from industrial slavery and be free industrial It killed five workers and wounded sixty others, among them several women. That act of murderous violence linked up perfectly with the expressed desire of murderous violence against the body of Frank P. Walsh.

It was followed with the usual perfect precision of the political-legal machine of the state in arresting the wrong men–in arresting and committing to jail not the employers who had talked or acted murderously, but the victims of the murderous talk and action–some of them wounded, more of them not wounded because they were not there.

The guards and the coroner and the state’s attorney made one mistake. They did not “get” Wiljem Laakso, Eskimo from the north of Finland, American strike picket from the same compassless humanity that led Ibrahim Omar into the front ranks to be shot down by the guards.

Wiljem Laakso had talked brotherhood and workmen’s solidarity to the strikers. By all the rules of that second day of May he had deserved “assassination”–the Capital punishment that only in this United States private Capital is permitted to administer from its own hands. “I stand with you,” Laakso had said to a great mass meeting of the workers–“I stand with you because you my brother, I your brother. I come from Finland to Conneaut Harbor in Ohio. I come here to Pittsburgh. It’s all the same where I come from. I come here. We workers stand together.” Pole and Lithuanian, Turk and Englishman and Irishman all had shouted tremendously when Laakso had come modestly to tell why he had been the most tireless picket of all. They shouted again at his brotherhood talk.

That brotherhood talk and that brotherhood spirit had to be suppressed. They were dangerous. The brotherhood spirit actually had spread to the police force of North Braddock. Every man of the ten men on the force had refused to serve on guard duty for the Steel Trust’s Edgar Thomson plant. They would not line up with the Coal and Iron Guards of Gary. They would not place themselves under orders to shoot their neighbors-workers who talked and practised brotherhood for the rights to eat and to have leisure and to bring up their families decently. Of course the policemen were discharged by the borough commissioners–“for the honor of the borough of North Braddock”–it being deeply dishonorable in Steel Trust ethics for policemen to be brothers with workers.

The ferocity with which the plant was “protected” in the “riot”–in which not a single guard or detective or company man was hurt–was no doubt infecting the police! The ferocity with which Fred Merrick and John Hall and Anna Bell and eight or nine others of the strike’s leaders had been jailed–without bail and without due process of justice–had sprung, too, from the same reasoned terror of brotherhood–brotherhood become a contagion in the very blood of the state.

Fred Merrick had quoted the Constitutional Bill of Rights for the right of citizens to bear arms. At a meeting of workers he had displayed a shotgun as Exhibit A to his constitutional remarks. He had assumed that the right of self-defense was the same in a man who worked 12 hours a day as in a man who rested 24 hours a day. For that he was logically a marked man for the coroner, who, in the ghoulishly candid code of the Pittsburg industrial district, is given jurisdiction for such emergencies. John Hall had asked for more wages and fewer hours of work. The “American Industrial Union,” a small and loosely federated body among the many thousand Westinghouse workers, was his creation. He was sent to jail, too–the reason being that he was not where he could be shot when the shooting was doing. It is only fair to the coroner to say that he would not have put Hall in jail if he had been shot by the guards.

To jail along with Merrick and Hall the coroner sent Anna Bell–also on a charge of accessory to the murder of her friends and comrades in the strike, friends and comrades whom the guards had killed. The Joan of Arc of the strike, Anna Bell had been called. When the men started out from the Westinghouse Electric plant the first day of the strike, April 21, Anna had waved her coat above her head and had run through the workshop aisles shouting, “Come on, girls, don’t scab.” And they came and didn’t scab. Anna’s philosophy of work and life was simple and dangerous. “The girls start in section E at 98 cents, and when they get into section T they start at $1; but, believe me, Mister, them few cents counts”–a simple and dangerous philosophy, denoting a sense of the value of money much to be discouraged in a worker.

Poor little Joan of Arc, who was only sent to jail without bond and without trial because the strike had aroused a sort of unreasoning historic prejudice. On the side lines of the strike in May was Bridget Kenny, the Joan of the 1914 walkout. In that other strike “Biddy” Kenny had stood in front of the state constabulary waving an American flag. “Ye think so much o’ the stars and stripes, git down and salute thim now,” she cried. They did, all of them.

“No, sire, it is a revolution,” said the Minister of Louis Sixteenth to whom the Bourbon had spoken of “the revolt.”

There are fluctuations, ups and downs, surgences and resurgences in every changing order, in every dramatic period of every changing order, in every intense phase of every such period. The Pittsburg strike, revolt or revolution came nourished with a deep, abounding sustenance. It sprang out of the unorganized working class–out of its misery and out of its aspiration. It illustrated all the patience of the workers, their heroism, their desire, their splendid springs of revolt.

It sprang toward organization. It sprang toward self-mastery.

The guns were all in the hands of the organized employers. The state militia and the processes of the courts were all in their hands. If against those odds the tide of revolt ebbs back, let no one be fooled. The waves of revolt are piled up and are piling up for a higher flood tide.

The workers in the Pittsburg industrial district have memories. Memories of suffering, of degradation, of humiliating slavery at the hands of employing masters, too incompetent even to “give” them a meager living. Memories that start in hot anger when the master employers advertise now of wages lost because of the strike–memories of wages and earnings never received when it was to the interest of the employers to strike and close their plants. The workers have been striking for the eight-hour day and have been told that it is “impossible.” They remember when the Westinghouse plants of Pittsburg forced them to an eight hour day for three days a week each alternate week. Their wages then, in 1908, had average, for skilled men and unskilled men, $14.40 a month.

From January 1, 1915, to September 15, 1915, the average wage received by unskilled workers in typical Pittsburg plants (one of them a Carnegie Steel Trust mill) was $4.66 a week.

When 40,000 men and women of one industrial concern (only 1,000 of them allied with trade unions) quit their work together on a hasty summons; when quite as many more in allied industries in the same district cease their work in quick harmony of revolt; when only slaughter and the threat of further slaughter keeps profit-making on its legs; when slaughter succeeds and dominates still only because the few employers and their guards are disciplined and organized and the many workers are undisciplined and unorganized–then the violent panic of employers protected temporarily by the Steel Trust guards can be appreciated. When these things are, and when Labor has its opportunity and realizes it (even though as yet only haltingly) then one can appreciate, too, the frightened rage which wishes the assassination of changers of an industrial hell.

The Masses is among the most important, and best, radical journals of 20th century America. It was started in 1911 as an illustrated socialist monthly by Dutch immigrant Piet Vlag, who shortly left the magazine. It was then edited by Max Eastman who wrote in his first editorial: “A Free Magazine — This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.” The Masses successfully combined arts and politics and was the voice of urban, cosmopolitan, liberatory socialism. It became the leading anti-war voice in the run-up to World War One and helped to popularize industrial unions and support of workers strikes. It was sexually and culturally emancipatory, which placed it both politically and socially and odds the leadership of the Socialist Party, which also found support in its pages. The art, art criticism, and literature it featured was all imbued with its, increasing, radicalism. Floyd Dell was it literature editor and saw to the publication of important works and writers. Its radicalism and anti-war stance brought Federal charges against its editors for attempting to disrupt conscription during World War One which closed the paper in 1917. The editors returned in early 1918 with the adopted the name of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, which continued the interest in culture and the arts as well as the aesthetic of The Masses. Contributors to this essential publication of the US left included: Sherwood Anderson, Cornelia Barns, George Bellows, Louise Bryant, Arthur B. Davies, Dorothy Day, Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Wanda Gag, Jack London, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Inez Milholland, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Carl Sandburg, John French Sloan, Upton Sinclair, Louis Untermeyer, Mary Heaton Vorse, and Art Young.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/masses/issues/tamiment/t63-v08n09-m61-jul-1916.pdf