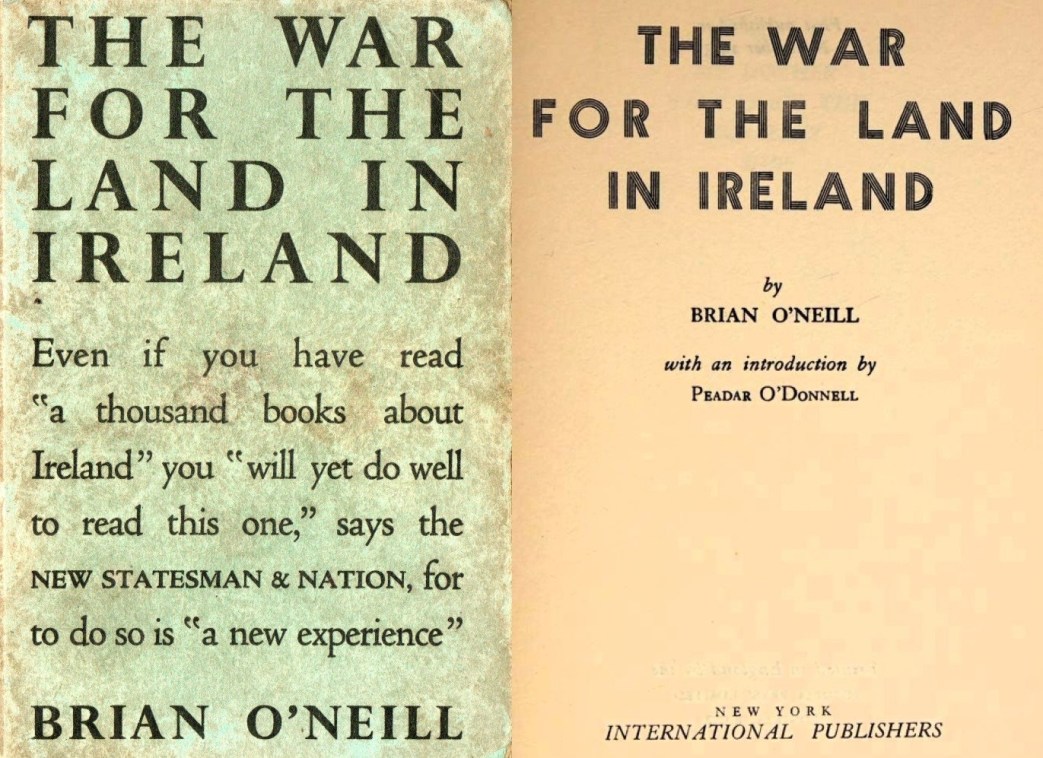

Brian O’Neill’s 1933 Marxist study, “The War for the Land in Ireland,” traces indigenous Ireland’s dispossession and its centuries of struggle to reclaim the land from the invaders, settlers, and landlords. Below are two worthy reviews—one from James Shields (born to Irish parent in Scotland, Chair of the South African Communist Party in the 1920s, and later a leading figure of the British C.P.), the other from Martin Moriarty (a leader of the British C.P.’s Connolly Association and on his move to the U.S., the Irish Workers Clubs). O’Neill was a young American-Irish (possibly born to an Irish family in Pennsylvania as Frank Ward, to also write under ‘Aodh MacManus’ and ‘Seumas MacKee’), by 1933 living in Dublin as editor of ‘Irish Workers Voice’, paper of the new Communist Party of Ireland. There he finished this work, with a formidable introduction by veteran left-wing I.R.A. leader Peadar O’Donnell. Though long out of print, this important forgotten work is freely available as a PDF. While clearly the ’peasant question’, so long a predominant feature of Ireland’s strife, is no longer a central issue in the overwhelmingly working class country, the quality of O’Neill’s work continues to illuminate Irish history, its recent revolutions and counter-revolution, and the larger processes of imperialist colonization not unique to Ireland.

‘The War for the Land in Ireland’ by Brian O’Neill reviewed by James Shields and Martin Moriarty, 1934.

‘The War for the Land in Ireland’ by J. Shields from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 14. No. 8. February 9, 1934.

Written by a member of the Young Irish Communist Party. this is a book which strikingly portrays the course of the Irish land struggle during the past two hundred years, and analyses it from the revolutionary working class standpoint.

With keen Marxist penetration and accuracy, Brian O’Neill traces the struggles of the Irish peasant masses right from the end of the Cromwellian settlement up until the present moment. Throughout the pages of the book he gives a gripping account of the age-long fight of the Irish countryside against rack-renting landlordism and the tyrannical domination exercised over the Irish people by the merciless bloodsucking British bourgeoisie.

The despotic yoke of British capitalist might has wrought almost indescribable havoc and ruin upon generation after generation of the Irish people. The record of Britain’s reign, as O’Neill impressively demonstrates, has been written over Ireland in figures of appalling mass impoverishment, famine upon famine, wholesale eviction of the poor peasantry from the land, and the widespread use of unbridled terrorism against the Irish masses.

This book shows the monstrous character of the early exploitation of Ireland by the English landlords, gives details of the enormous sums of plunder which were extracted to fill the pockets of the latter, and presents a graphic picture of the deliberate ruination of Irish agriculture by the British ruling class.

As Frederick Engels states in his book, “Conditions of the Working Class in England in 1844,”

“the rapid extension of English industry could not have taken place if England had not possessed in the numerous and impoverished population of Ireland a reserve at command.”

Brian O’Neill makes clear how this reserve was created by the hounding of the Irish peasantry from the land and the terrible ravages of the great Hunger, for which the British bourgeoisie were criminally responsible.

He shows how time and again the masses of Ireland have risen in open revolt, and deals at length with the many heroic struggle which they have waged for their emancipation.

The history of Ireland, as this book demonstrates, is rich revolutionary struggle. But it is also characterised by a long record of betrayal of that struggle at the hands of petty-bourgeois and capitalist leadership, whose vacillations, compromises with the enemy, and outright acts of treachery have time and time again robbed the struggling Irish masses of success.

This is fully outlined by the author in describing the early and later land struggles from the time of the Ribbonmen, the Land Leaguers, etc., up to the present period when the British imperialis economic blockade of the Irish Free State is operating in full blast. The figures of such courageous fighters as Mitchell, Davitt, Lalor, are sketched in bold relief, and here also is set forth the defeat role of Parnell, the stifling activities undertaken by the leaders Sinn Fein, and the reactionary onslaughts of the Catholic clergy.

Drawing the lesson from the failure of the struggle in the past Brian O’Neill shows that only under the leadership of the Irish proletariat, led by its own Communist Party, can the fight for national and social emancipation be successfully carried, through to a finish.

He examines in detail the situation of Ireland in relation to the world agrarian crisis, and deals very effectively with the question of the revolutionary way out.

The brilliant achievements of the Russian workers and peasants are illustrated, and the triumphant progress of socialist agriculture, which the October Revolution of 1917 under Bolshevik leadership made possible, is presented as a glaring contrast to the chaos and ruination of agriculture under capitalism.

At the end of the book there is attached that part of the famous speech of Comrade Stalin, which was delivered in January, 1933, to the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party d the Soviet Union, wherein the achievements of the first Five-Year Plan in the field of agriculture are recorded.

The appendix also contains a number of useful informative tables concerning the number and size of Irish land holdings, tails of livestock, agricultural labourers’ wages, etc.

It is a book which, as Peadar O’Donnell, the well-known Republican Army leader states in his introduction, “will sparks” in Ireland.

And it will serve to further emphasise to the working class of Britain the need for still greater solidarity with and support of the struggle of the Irish masses against our common enemy, if the stranglehold of British imperialism upon both British and Irish workers is to be smashed.

For it is a fact which is inescapable, that the holding down of Ireland has not only meant the terrible ravaging and oppression of the Irish people but it has been the means of enabling the British bourgeoisie to rivet tighter the chains of wage slavery and capitalist exploitation upon the limbs of the British workers themselves.

Success in carrying forward the struggle for complete Irish independence is a vital issue for the working class of Britain they, too, hope to achieve their emancipation.

“The War for the Land in Ireland,” by Brian O’Neill, with an introduction by Peadar O’Donnell. London: Martin Lawrence. Ltd Cloth covers, 5s.; paper covers, 2s. 6d.

‘Who Can Free Ireland?’ by Martin Moriarty from New Masses. Vol. 11 No. 3. April 17, 1934.

THE WAR FOR THE LAND IN IRELAND, by Brian O’Neill. International Publishers. $1.50.

Within the framework of international antagonisms, the swift drive for war between the British and American empires emphasizes anew an observation made by Lenin in his defense of the Irish Insurrection of 1916. Certain Socialists had brushed aside the Easter Week revolt as a defeatist conspiracy of no consequence.

Fiercely deriding this viewpoint, Lenin declared: “A blow of equal strength, when struck against the power of the English imperialist bourgeoisie by a rebellion in Ireland, will have a hundred times greater political effect than if it occurred in Asia or Africa. In “The War for the Land in Ireland” Brian O’Neill digs to the roots of this international “nuisance.” It arises from the ancient battle of the Irish poor to wrest a living from the soil, to wrest the soil from the Gentlemen of Property. Not that this is “just an agrarian question” as the Social-Democrats of 1916 parroted and as many well-meaning radicals repeat even today. Virgin Socialists of the Second International were blind to an imperialism which begets its own “little” ironies: the Irish question becomes as far-flung as the oppressing “empire on which the sun never sets.” It influences the war machinery of British and American empires. “Ireland without British naval bases?” English ministers cry in horror. “Ireland’s coast, potential war base of an enemy power, unguarded by British wireless stations? England cut adrift from her source of food supply? From such disasters may God and our field guns preserve us!”

Scattered over the earth, the Irish brood over black and bitter memories of clearance and famine, of coercion and transportation enforced by bestial Christians of the empire. Profound hatred of everything British does not cease with the first generation. It spurs on the Fenians seeking vengeance in America as in 1866; and if their raid on Canada (unofficially encouraged by the United States) failed, nobody denies the British empire’s fathers were scared. Thousands of the dispossessed are forced by economic conscription into the British Army. There they preach “sedition” as they did in India during the war. British generals were then rubbing their hands over the slaughter of the Dublin insurgents. But when the last firing squad had butchered the last rebel, the generals were appalled by another mutiny–a sympathetic outburst (in India!) led by Irishmen of the Connaught Rangers’ Regiment.

Strengthened by revolutionaries hounded from Ireland after the Anglo-Irish wars, the huge Irish population here is a jealous prize of skilled demagogues. They play upon a widespread anti-British sentiment which is rooted in a revolutionary struggle against British domain in Ireland. They fashion this sentiment in a weapon of the U.S. Navy League against the ex-queen of the seas: “Build a Navy Second to None! Make England Pay her Just War Debts to the American People!”

Hence the Irish question is no mere nationalist noise. It is more and more of international concern to the labor movement.

“Who would own and control the land?” James Connolly, Easter Week’s socialist hero, infused a new and vibrant meaning into the Irish revolution when he posed this question as the dynamo of Irish politics in his classic Labor in Irish History in 1910. “Who owns the land?” This was the question that famished peasants sought to answer with pike and gun in the revolutionary explosions of 1798 and 1848 and 1867 and the black years between a heroic background for middle class knaves to whom the revolution was a platform oration. “Who owns the land?” asked the Moonlighters, the Whiteboys, the Hearts of Steel as they houghed cattle, levelled enclosures and shot rackrenters. These annals of the Irish landless were written by Ireland’s greatest revolutionary “that other and abler pens may demonstrate the manner in which economic conditions have dominated our Irish history.”

Where else those “other pens” than in the revolutionary working class? Brian O’Neill, spokesman of the young Communist Party in Ireland, worthily carries forward the tradition of Connolly. Tersely and dramatically he unfolds the broad sweep of the land war and hammers away at its vital lessons: the poor fought; the rich betrayed. But betrayals then and now are not defections peculiar to individuals, O’Neill shows. Betrayals are shaped by the pressure of class forces and class ideas. Wrong programs can strangle a movement as effectively as nests of informers. Take the Fenian revolt of 1867, about which O’Neill gives his best writing. Discontent smouldered over the countryside after the great famine and tithe wars of the ’48 period. From the “rough and ready roving boys” of the agrarian rebel lodges arose the Fenians (the name is derived from the traditional Fianna, the military defenders of ancient Ireland,) who saw a military insurrection alone as the escape from national slavery. But though the leaders recruited from the poor of town and country, though they roundly denounced “the thuggery of the landlords,” they dodged the land question organizationally and thus their bravery when they did take to the field does not disprove this–dislodged from the revolution one of its most powerful forces.

What a lesson for certain Irish revolutionaries today! How well does this keen analysis of the Fenian movement–the grandfather of the Irish Republican Army of today–answer those who seek to free Ireland by a military coup, to be accomplished by select bands of skilled marksmen wholly unconcerned with such trifles as evictions and unemployment and wage-cuts.

Then which class and which program can free Ireland? O’Neill asks. Certainly not the wealthy cattle ranchers who want a grazing land for bullocks. Nor the business men of Fianna Fail who paint lofty visions of peasant proprietorship. (“Wiping out peasant proprietorship is an integral feature of bourgeois society.”) Nor can the poor farmers, for all their gallant fights of yesterday and today. The farmers are scattered. They have not the industrial discipline which binds the working class together into a solid fighting army. And as Peadar O’Donnell, an outstanding leader of the Irish Republican Army, notes in his introduction (a little history within a history, by the way: “The small farmer dearly loves to see men of property on his platform.”

The solution? It has to be “the solution offered by James Connolly when he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in 1896: The forcible overthrow of capitalist-imperial- ism and the establishment of the Irish Workers’ and Working-Farmers’ Republic.”

That task can be carried out only by the “unconquered Irish working class” to whom Connolly dedicated his Labor in Irish History years ago. Ireland’s working-class historian was attacked-as Brian O’Neill will surely be attacked–by the hired scribblers of native Irish capitalism. But no cheap sneers could prevent Labor in Irish History from imprinting its lessons on the brain of the Irish working class. An eloquent proof is The War for the Land in Ireland.

Brian O’Neill has written a sturdy little history. Its insight is sharp and its conclusions bold and revolutionary. Its strength is the strength of its source: “the unconquered Irish working class, the incorruptible inheritors of the fight for freedom in Ireland.”

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.536586/2015.536586.The-War_text.pdf

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1934/v14n08-feb-09-1934-Inprecor-stan.pdf

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v11n03-apr-17-1934-NM.pdf