Direct action gets the goods in Grand Rapids as ‘night soil’ (human waste) workers make their point and win demands for themselves and their horses.

‘Justice is Blind, but it Can Smell’ by T.F.G. Dougherty from Industrial Worker. Vol. 4 No. 24. September 5, 1912.

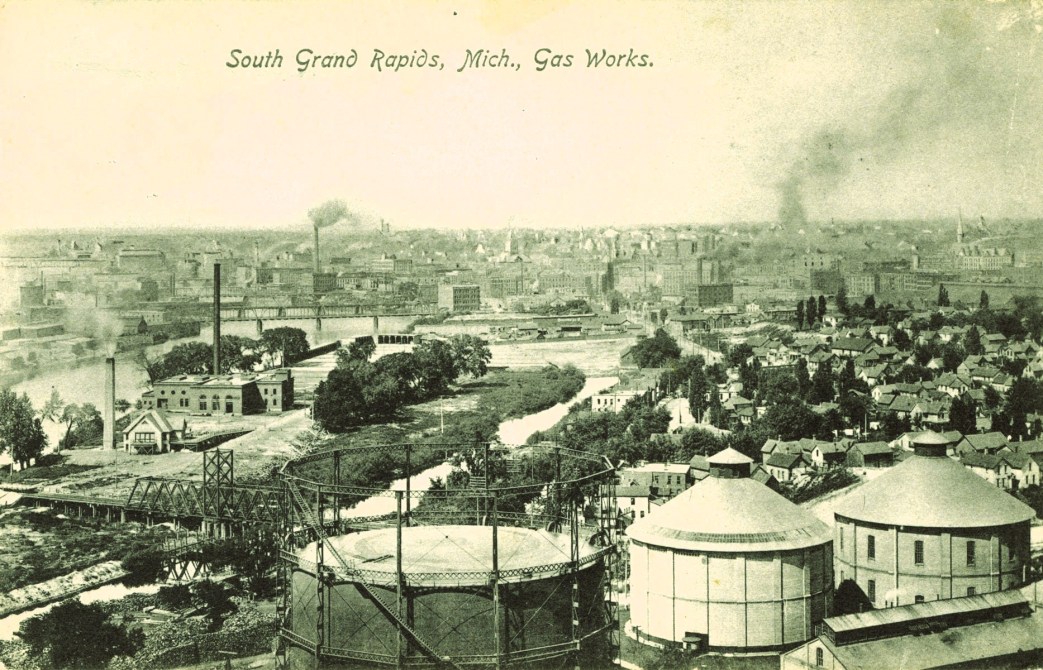

Some time ago the health board of Grand Rapids, Mich., appointed a new superintendent of the garbage and night soil department. The night soil is removed and disposed of by the “city” at so much per barrel, charged to the householders, and the slaves who do the actual work of removal are paid at the rate of ten cents per barrel for performing this useful service to society; for, if this human excrement were not removed and disposed of, it would be a stench in the delicate nostrils and a menace to the health of our useless masters; besides it might so increase the death rate of the useful slaves as to deplete the labor power market, thereby having a tendency to send up the price of this useful commodity.

The new superintendent thought it would be a good idea to have the night soil removers remain at the barn from one to twelve o’clock, thus knocking the slaves out of a trip and thereby reducing their “earnings” considerably. The slaves stood it for a few days, and then a few of them, who had “imbibed” some I.W.W. ideas, resolved to act directly. They got the other drivers together and explained to them the course of action they intended to pursue; the others readily assented, and so, attired in their work clothes, these men marched to the city hall and proceeded to the room occupied by the health board.

The city health officer, the clerk of the board, and two newspaper reporters were present when the men, who are humorously and thoughtlessly referred to as “honey dippers,” entered. The day was hot and sultry. The health officer endeavored to divert the attention of the men by a “pleasant” conversation, but the spokesman of the party called a halt at the start and said they had come on business. He stated their grievance, and by this time all the windows, transoms and doors had been flung wide open, the newspaper reporters had fled, and the health officer and the secretary kept smelling bottles to their nostrils. The men stated that they either wanted the trip restored or the price per barrel increased to 15 cents. The odor from their work clothes so strongly impressed the health officer with the “justness” of their grievance that a restoration of the trip was readily assented to, and the “boys” were implored to go back to the barn at once.

But the “boys” had another matter to settle, and the health officer, who by this time looked quite “sea sick,” told them to hurry. These men then demanded fly nets for the horses they drove, stating that the animals were cruelly tortured by flies, from which they were unprotected. This demand was also acceded to.

The spokesman called the officer’s attention to the fact that he could not stand the odor of their clothes and asked him how he would like to work in the vaults.

These men did not petition the health board, they did not go to the craft union workingman’s friend, Mayor Ellis; they did not wait till election day to cast a ballot for some social “resolutionist” who believed that under a plan of society laid out by Victor Berger, machinery would be developed to do this work, or mayhap Vic would place human society on a diet that would do away altogether with waste: nix, they got busy on the job right now, directly. They practically said to hell with Berger’s interminably “slow” evolutions that stretch out like Herbert Spencer’s “great unknowable.”

Now, here is an idea for the useful slave: Organize all the men in the garbage and night soil department, then drive your LOADED wagons up to the city hall and with your WORK CLOTHES on, assemble in the office of the health board and DEMAND a flat scale of $5.00 for an eight-hour day. PICK OUT A HOT DAY. Try it, fellow workers, and see what the result will be.

Think of the service these workers perform for society for a little more than $3 per day, working like hell to get that, besides being looked down upon by the rest of society, large numbers of whom would be “back to the soil (six feet back of it) were it not for their hard and poorly “rewarded” toil. Great system, but the DIRECT ACTION of the workers, industrially organized, can and shall change it.

“The emancipation of the workers must be the work of the workers themselves.”

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iw/v4n24-w180-sep-05-1912-IW.pdf