A moving report of The New York ‘funeral’ for John Reed with speeches by Max Eastman, Arturo Giovannitti, and others.

‘Workers Cheer Cause For Which Reed Died’ from The New York Call. Vol. 13 No. 300. October 26, 1920.

Thousands Gather to Hear of Deeds of Young Revolutionist Who Gave His Life That Labor Might Continue Its Onward March. Throng Suppresses Sobs.

In commemoration of the efforts of John Reed, a victim of typhus in Russia, thousands of his former associates in the movement of the workers and in the field of proletarian journalism gathered in the Central Opera House, East 67th Street, last night.

The vast audience, prone to mourn the ill-timed death of one of labor’s most sincere workers, soon responded to the sentiments of the speakers — “Jack Reed would not have us weep.” Cheering the appeals for a rededication to the cause for which Reed gave his life, the members of the audience with one accord gave evidence of their desire to act as Reed would have wished them to.

Nevertheless, despite the cheering and the singing of “The Internationale,” there was present a deep undercurrent of sadness.

Dances to Funeral Tones.

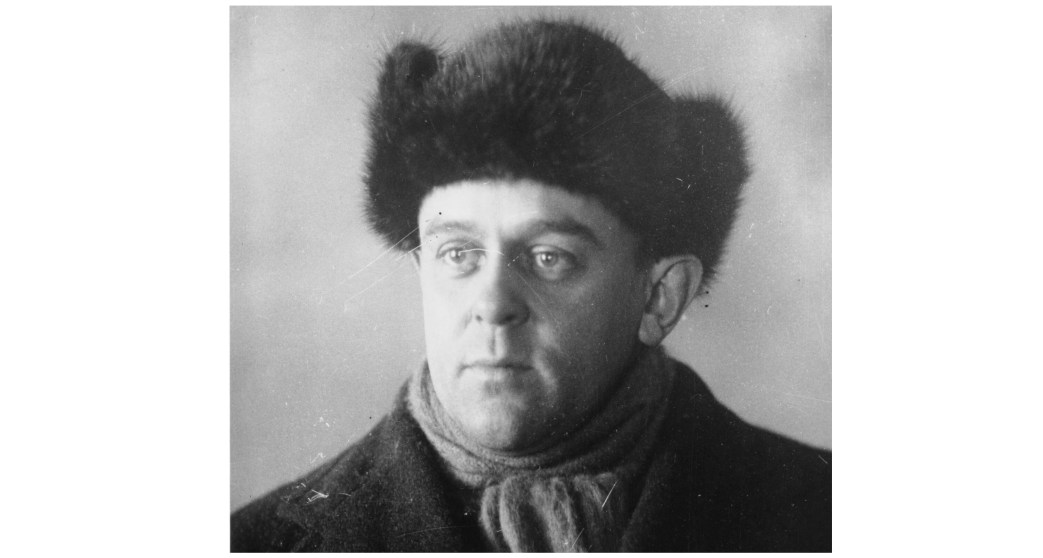

In the center of the platform was a large crayon drawing of Reed, drawn by Hugo Gellert. In marked contrast to the impressive sadness of a young girl who, draped in black, danced to funereal tones, was Reed’s face, with its flush that indicated only wholesome fun and adventure.

The attempts of hundreds of men and women to suppress their sobs, resulting in sudden gasps, was plainly evident through the dance. During it all, Reed’s eyes gleamed.

Arturo Giovannitti was the first speaker. Not a sound greeted his appearance. He started to speak, saying:

“Comrades, we are not here to weep and mourn. We do not mourn heroes. Nevertheless, the passion pent up in us is so great that it cannot be worthily expressed by word of mouth.”

“John Reed died as truly for the Russian Revolution as did any of the brave soldiers of the Red Army who fell on the 13 fronts of Russia. He gave his heart for the revolution, even as if his heart had been shattered by shrapnel.”

Reed was the ambassador of the American class conscious workers to Russia, Giovannitti said.

While the workers of all European countries were doing things of tangible value to the Russian Revolution, declared the Italian poet, the American workers alone were silent and did not lift a hand.

It was for Reed to go to Russia and die for the revolution so that the workers of this country might be saved from condemnation in the future, he said.

“This man died of typhus. A few ounces of American medicine might have saved his life. A little bottle of medicine that we could have bought at the drug store on the corner might have gone through the parcel post to save a life. But this could not be. The Americans have declared that no medicine will go to Russia.”

“He died but 4 days before his 34th birthday, the age of all the heroes of the world. The age of the Carpenter of Nazareth when he died on the cross; the age of Robespierre when he ascended the guillotine; the age of Shelley when he heard the call of the Revolution of 1821.”

In his eulogy of Reed, Giovannitti turned to another event. He said of the death of MacSwiney, in a London dungeon, that it was to be compared to the death of the American Communist.

“This day is twice hallowed. Mayor MacSwiney lies dead today. He died because of a hunger strike. So it was that Jack Reed also died of a hunger strike. And the saddest part of it all is that there are so many millions of others in that great Russia who are dying of a hunger strike. MacSwiney lasted 74 days and Jack Reed starved 4 months. The workers of Russia are now starving in the dungeon of the Allies, even as MacSwiney died in the dungeon of the British Empire.”

“I repeat, let us not weep,” Giovannitti concluded.

“Let us answer Jack’s call. I can see him waving the red flag of the international revolution. Let us give him a fitting burial. Let his body be placed on the pyre of the martyrs of history. But from the flames let us snatch his big, palpating, beating heart and hold it up to the sun, saying, “Hurry on sun in your course, travel faster so that soon you may fly over the White House as you do the Kremlin.”

Max Eastman, editor of The Liberator, to which magazine Reed was a frequent contributor, also spoke. He told of the days when The Masses was in the process of formation. Reed’s persistency alone, said Eastman, forced the publication of the magazine, now suppressed by the government.

“Reed Chose Truth.”

“What a load of bad judgment, coupled with enthusiasm, Reed brought into our editorial conclaves,” Eastman remarked. He said that Reed had to choose between the popular hypocrisy of capitalist journalism and lonely truth with the workers’ press, and without wavering chose the latter.

A message from Ben Gitlow, now imprisoned in Dannemora, was read to the audience. He said that it was hard to believe “that the cheery good-bye and good luck of a year ago was not to know a hello.”

Ludwig Lore, editor of the Volkszeitung, spoke in German. The audience made a liberal response to an appeal for contributions, which will go to purchasing a memorial for Reed.

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.