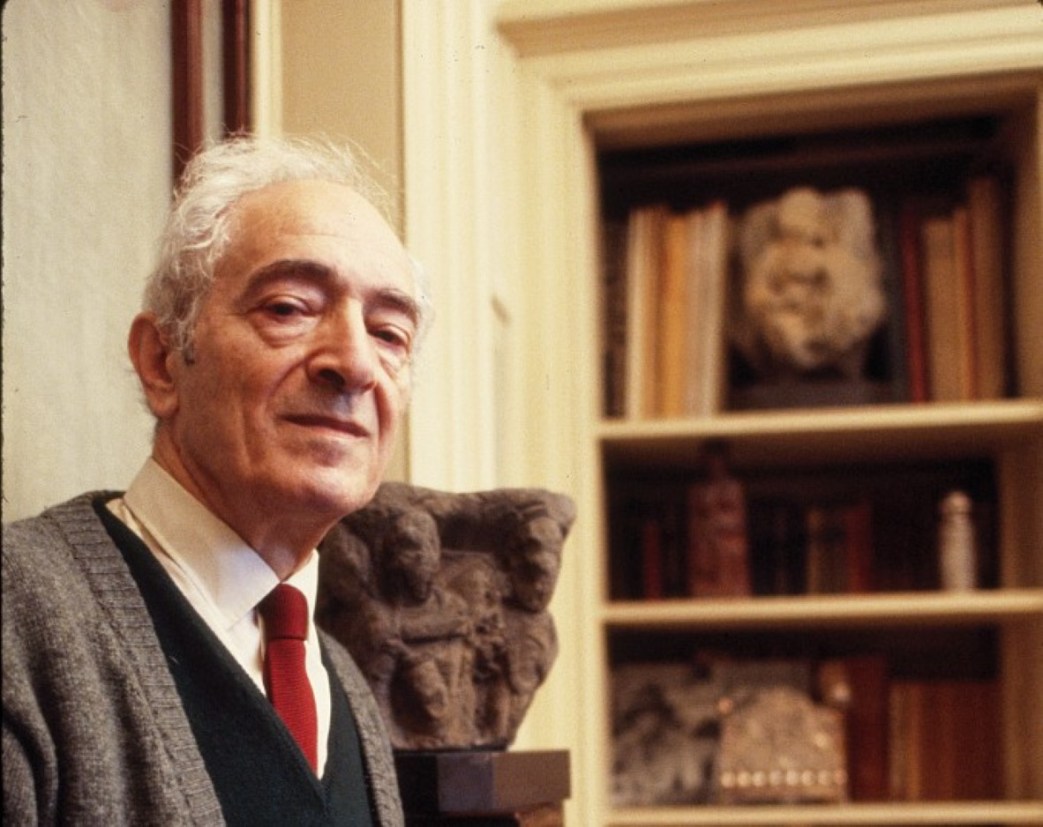

Prudes have often attacked Hollywood as a morally degenerative influence in present society, when in reality Hollywood helps to shape and uphold society’s dominant conservative mores. In another fine essay, Marxist art critic Meyer Schapiro reviews Catholic philosopher Mortimer J. Adler’s Art and Prudence, and with it the relationship of the Church’s demand for a metaphysical world view with Hollywood’s machine of bourgeois myth-making.

‘A Metaphysics for the Movies’ by Meyer Schapiro from Marxist Quarterly. Vol. 1 No. 3. October-December, 1937.

In Professor Adler’s book on Art and Prudence1—the conflict between the value of the movies as an art and their possible dangers to morality—the movies have at last found a metaphysical justification of their vices and virtues, and even of their existence. The owners of the moving-picture industry, having been disturbed by the charges of various moral agencies and investigators that the movies are bad for the morals of the audience, entrusted Adler with the task of criticizing these opinions. His report to the industry and his views on the relations of the film and morality fill a considerable part of the volume. With great care he demonstrates that most of the charges are based on opinion and not on knowledge, that several of the investigations which have supported these charges are scientifically defective, and that we lack reliable knowledge of the influence of the movies, so that a sound practical conclusion is impossible. He admits finally that the problem is almost insoluble, except by “a perfected Christian wisdom”; the best one can do is to keep the children away from bad movies; censorship or extirpation is impossible.

The interest of the book hardly lies in this conclusion. Certainly the latter does not require the immense arsenal of argument and the seven hundred pages of analytical bombardment which Adler brings to his attack on the question. But it is apparent that the morals of the movies are only the occasion for expounding and applying principles nearer to his heart than this limited subject matter. The core of the discussion is not so much the movies as the author’s ideas on philosophy, morals, society, science, religion, metaphysics, tradition, esthetics and education, in fact on everything but contraception and war. If its length seems disproportionate to the results—-the latter could be deduced more simply and directly and from assumptions less extensive than his own—on the other hand, the presuppositions which are the real interest of the book are insufficiently developed in proportion to the author’s claims. The first principles are not systematically stated, nor are the difficulties of his position met. And in the same way, the social aspects of the movies relevant to the artistic and moral questions are completely neglected. Hollywood is absent or is masked by transpositions into general categories, and the material grounds of moral conflict evaded. And although the author speaks constantly of a superior Christian wisdom and morality in the light of which alone the conflicts of art and morals, not to mention the greater social struggles, can be resolved, these eternal criteria of man’s ultimate good are not applied to the movies. His analysis of the esthetics of the film, patterned on Aristotle, contains hardly a single independent reference to the structure of an actual film. Hence the book has a misshapen magnitude; it abounds in everything but what the critical reader looks for in the contexts introduced by the author.

What unites the opinions in this work is not so much their consistency as the programmatic assertion of a Catholic or perennial philosophy. It is part of the tendency toward the reinstatement of metaphysics as a superior knowledge which already has adherents in the universities; one of the most aggressive movements in educational theory proceeds from assumptions like his own. The criticism of the schools by President Hutchins2 of the University of Chicago calls finally for a return to metaphysical first principles not merely as a matter for disinterested contemplation, but as the necessary basis for the solution of contemporary social and economic problems. Now Adler’s book, which deals with a “practical” question, therefore provides at least one test of these theoretical claims, a test all the more significant since few Catholic writers are so insistent on the need for logical rigor. The convergence of his principles on the problem of the movies is especially piquant; for the movies, the most modern of the arts, become the entering wedge of his traditional metaphysics. The newest art is examined in order to confirm the oldest wisdom, and the movies are shown to conform to Aristotle’s analysis of art. But behind this intellectual tour de force lie the more serious purposes of Hollywood and the Catholic church: the first is defended against its secular critics and the second is presented to Hollywood as its proper ally and the real bulwark of morality.

I. The First Principles

Adler contrasts the uncertainties and shabbiness of our everyday empirical knowledge and even the results of scientific investigation—”which of course (sic) adds nothing in the way of ideas”—with the self-evident truth and “completeness” of first principles and the propositions deduced from them. Hence he distinguishes two levels of knowledge, the knowledge of first principles or self-evident truths, and the knowledge of things tainted by contingency, which can at best be opinion and not true knowledge. Within this lower level, however, he sets apart the data of the natural sciences, which constitute probable knowledge, though not certainties, from the data of the sciences of man—psychology, history, etc.——which are merely an unscientific and prejudiced report of particulars and are usually unreliable.

What are these certain and “complete” principles and what are the grounds for his belief that they are self-evident? Neither the principles nor the grounds are submitted connectedly for the reader’s examination, but some of the principles can be picked up in the course of the argument. They are so vaguely stated and applied that when Adler attributes self-evidence to a proposition it is unclear whether he means it literally or is using the rhetoric of the pulpit. The principles are simply assertions of constancy, that human nature is always. essentially the same, that “common experience is always and everywhere the same, as man and the world are,” that “moral principles are everywhere basically the same,” that “the nature of art can be stated with finality,” etc., etc. It is this constancy which is the subject-matter and basis of philosophy as distinguished from the inferior field of science. “Philosophy rests upon common experience, arising therefrom by reflection…The metaphysician and the mathematician do not need any more experience than that which is possessed by the least experienced of men.” The practical importance of metaphysics lies in just this independence of special experience and history. Dealing with unchangeable essences and possessing an eternal truth “which is therefore traditional and conservative,” Adler can easily deduce from the self-evident principles a necessary hierarchy of mankind and the virtue of submission to the existing order. Obviously, if society is in its essence always the same, the good man conforms and non-conformity to custom, according to Adler, is contrary to nature; it is morally vicious, anti-social and a sin (pp. 163-65).

As a philosopher who begins by distinguishing true knowledge from opinion or merely probable knowledge according to the element of contingency present in the objects of the latter, it is surprising that Adler can still attribute certainty and necessity to statements about nature, man, society and experience. If these are subject to contingency, as he says again and again, then no synthetic statement about them can be more than probable. But by the very admission of their contingency it also becomes ambiguous to say that these things are always the same. What is it in them that is always the same? and what is it that changes? and how can we know in a given practical context whether what is in question is the invariant or changing? The meaning of terms like “basic,” “essential” and “same” are nowhere explicated in spite of the constant iteration of the author’s demand for rigor in those he criticizes.

But apart from this vagueness and ambiguity, the principles are suspicious because of the contradictions that appear in their application. The principles are said to rest on experience, but their truth is also said to be independent of questions of fact, as if they were tautologies or analytic statements.3 They cannot depend on questions of fact since appeal to fact, by his own word, can only yield probabilities, not certainties, whereas the principles are necessary and self-evident. Yet the universality of the principles is made to depend finally on experience, and it is even presented as a certainty that experience is always basically the same, although this can never be verified and this non-verifiability is no less probable than the assertion that experience is always the same.

II. Human Nature and Morality

Now consider, for example, Adler’s principles of human nature. Although he asserts that human nature is always basically the same, he tells us that human behavior is unpredictable. It is unpredictable not only because subject to accidents, but because the will is free–man being a rational creature endowed with something of God’s essence. If two men are completely alike, and are in identical circumstances, according to Adler they will clearly behave differently since each has a free will. Thus reason becomes an element of contingency in human behavior and, moreover, with the will (contrary to Thomist teaching), a principle of individuation. The will being free and uncaused, like God, we cannot know the effects of various things on behavior. And since the power of choice is unconditioned yet variable, choice itself becomes meaningless or unintelligible. Human nature, however, is described as different by Professor Adler when affected by divine grace than when unaffected, when guided by Catholic principles than when unbaptized. Man is unpredictable, not because he is irrational, but because he is rational. A scientific empirical psychology he holds to be impossible, but man can discover by his reason self-evident first truths about his soul. But of such necessary truths Adler gives no convincing examples; his psychological statements are either meaningless views like the “basic principle of the separation of reason and the body” or common-sense observations.

Whatever his views on the caused and unpredictable nature of human behavior, Adler cannot touch on any subject without committing himself to predictions about man and the consequences of such and such influences on his behavior. In posing the problem of the effect of the movies on human feeling and action, whether esthetic or moral, he assumes that man is affected in his behavior by given causes; even his rules of art are rooted in observations, interpreted as cause and effect. If in one place he asserts in defense of Hollywood that we have no scientific knowledge of the effects of the arts or spectacles on behavior, elsewhere he accepts as a matter of fact the charges of the Christian fathers that the Roman spectacles were ruinous to morality and attributes changes in taste to particular social and psychological causes. And although he insists rightly on man’s distinctive capacity to modify himself as well as his surroundings he denies this to the artist: the arts are “only a mirror of already existing manners and morals.” Certainly the virtue of prudence, the taking of counsel with regard to action, would be impossible unless the effects and causes of behavior were knowable. And Adler himself, in denouncing the social scientists who adopt a social relativism with regard to moral standards, predicts that if their teaching is not extirpated civilization will perish; and in spite of his disavowal of prediction in social affairs he is sure that only Christianity will save man and solve his earthly problems.

Nothing in this book, it seems to me, is more contradictory, yet more dogmatic, than Adler’s ideas about morality. On the one hand, he tells us that failure to conform to local customs is anti-social and morally vicious, since these customs are the momentary determinations of the basic and eternal principles of morality. By the same token, on the other hand, he considers it morally pernicious to present virtue as always rewarded and vice as always punished (perfect justice is reserved for the Last Judgment); yet the movies, which by his own admission exhibit this pernicious view of vice and virtue, he will not permit to be called immoral since they conform in their morality to the customs and views of the modern Christian community. Moreover, the movies are made for a hierarchy of people with different needs and capacities, and for some of them it is congenial to see vice always punished and virtue always rewarded. He admits ignorance of how arts affect behavior, but he asserts that by getting the art they need people are kept from crime and the community is preserved. And finally, it is wrong to criticize the arts for their effects on morals and manners, since the arts are “only a mirror reflecting the already existing manners and morals of their time.” Verily, “our” Adler is both a menace to morality and its greatest defender. It becomes doubtful, after reading him, that immorality is possible or that there is a Christian morality distinct from others. The pagan arts, he says, were offensive to Christians as “transgressions of Christian values and manners. But Christian manners [and why not values?] are no less conventional than other manners. They have changed from time to time, although always remaining expressions of Christian morality, since as conventions they are determinations of the principles of that morality. What Christians find offensive has, therefore, changed in the course of centuries.” But since the “basic principles of morality are everywhere the same,” it is evident that the moral difference between Christianity and paganism is merely conventional, at any rate not basic. The church fathers asserted again and again that they did not differ from the pagans in their manners, but unlike Adler they also insisted on the moral difference and sometimes defended the moral right to disobey what they considered unjust laws.

III. The Rules of Art

All of Adler’s general principles with regard to the arts are also compromised by ambiguous statements. The rules of the arts cannot be violated, he Says, except by genius. But these principles are simply a description of the arts as practised. Are the rules based then on the works of non-genius? And if mediocre works adhere to them without success and genius violates them with impunity, what sense do they have as rules of art? What determines the selection of relevant examples from which the rules are to be deduced? But in spite of his admission that the rules are descriptions of the arts as practised and that these arts are subject to historical change, Adler employs the rules academically, as if they were absolute principles, to set limits to the arts and to judge particular works. Art becomes a metaphysical entity of which “the nature can be stated with finality.” Only from such a view could he write that everything to be said about the movies was said before the movies existed; nevertheless he is compelled to add later, in describing present practice, that new inventions will change the character of the movies and the full nature of the movies is still problematic. Armed with his first principles and the fullness of his prehistoric knowledge of the movies, it is natural that he should find the modern empirical literature on the movies “vaguely discursive” and that his own account of the esthetics of the film should be so poor in concrete illustration. But at the same time he draws heavily on these vaguely discursive writers and has to acknowledge their “clear formulations” and “insights.”

IV. The True Nature or Democracy

In the field of society this pretension to first principles and to a profounder knowledge than is given to mere empiricists, leads to the greatest absurdities. Adler e.g. attempts to describe the nature of democracy in its “deepest sense,” and discovers that it lies in modern technology which imposes on all governments to-day the same submission to the will of the people. In this “deepest sense” the governments of Italy, Germany, Russia, the United States and England are all democratic.4 But having identified democracy with the use of radios and machines—the United States being no less democratic than Italy since here, too, the trains run on time—he tells us that Elizabethan England was also democratic, in spite of the monarchical form of government, because of the democratic spirit of the citizens. And in discussing the democratic as distinguished from the classic and Christian views of the problem of art and prudence he cites the writings of Milton, Rousseau and Tolstoy, all belonging to pre-modern technology, as examples of democratic opinion. Further, while he speaks of the individualism of Milton, his refusal to let the state regulate his own moral welfare, as “a peculiarly modern note and one of the expressions of the democratic temper,” he includes fascism as democratic, although he admits elsewhere that it regulates every detail of individual life. His conception of democracy is contrary to his own principles since he defines an order of government by an order of technology, an effect by one of its possible, but not sufficient causes. More essential to democracy is the concept of individual rights; it is by the limitations and extensions of these rights that we judge a government to be more or less democratic and not by the character of its vehicles and traffic. The very classification of views on art as Greek, Christian and Democratic indicates the arbitrariness of Professor Adler’s thought; for these three categories—a cultural, a religious and a political—are hardly comparable and conceal the feudal aspect of the Christian stage. The analysis terminates in the view that since democracy, i.e. fascism, communist dictatorship and liberal representative government, is the modern political form, the Catholic church accepts it as the status quo and considers its conditions in solving the problem of art and prudence.

V. The Christian Tradition

But in doing so, the church maintains its perennial philosophy inherited from Aristotle and Plato. This tradition is described as unified, unchanging and non-progressive, advancing only by a sharpening of analysis, by a dialectic growth toward higher syntheses, never through new experience. Inspired also by divine truth, which is transmitted through the canonical books of the Bible, Catholicism is declared to be the only doctrine that can solve the issues of our time. There can “obviously” be no conflict between Catholicism and science, for the latter as a product of reason, issuing finally from God, can hardly be inconsistent with the divine revelation. But Adler has still another guarantee of this harmony of truths in the imposing choice he offers the reader: either you accept Catholicism, in which case there is for you no conflict with science, or you do not accept it, in which case, by “a higher dialectical principle,” you must take its doctrines on their face value as revelations of divine truth (p. 55). Before these clear alternatives who can dare to doubt the Virgin Birth or the Resurrection of the Dead!

Throughout this argument Adler arbitrarily assumes a unity of Christian doctrine for which there exists no historical evidence. By an elegant but obvious selection of texts he tries to present a Catholic view on art and prudence as a dialectical synthesis of Plato and Aristotle; the moralism of the first and the catharsis of the second, sophistically regarded as opposites, are fused in a higher Christian theory which synthesises both aspects. But he has to admit that Aristotle already sees both aspects of the problem and that Christianity in general inclines to the Platonic moralism rather than to a synthesis. What then is the unique Christian synthesis? It lies, Adler tells us, in the problem of Church and State, in Thomas Aquinas’ view that the State ought to extirpate immoral arts. How does this differ from the classic view? He is willingly obscure on this relation of Church and State; certainly, in his own consideration of art and prudence, which he declares to be guided by Christian principles, the state is left out altogether. Yet in this omission he runs counter to the highest spokesman of the church, the present pope, who vigorously recommends the intervention of the secular arm. Hence the trim dialectical synthesis in Catholic wisdom turns out to be irrelevant to Adler’s learned conclusions which in turn contradict the last encyclical of the pope.

It should be observed at this point that although Adler attacks with unbridled vehemence, and in the aroused manner of one who is defending the most sacred values, those writers who speak of the bad effects of the movies without having supported their opinions by the most rigorous method, and opposes to their laxity the superior wisdom of the perennial Christian-Aristotelean tradition, yet he passes over in complete silence the equally loose statement of the pope on the same matter, a statement which he undoubtedly knows since other parts of the encyclical are quoted in the book: “Now then it is a certainty that can readily be verified that the more marvellous the progress of the modern motion picture art and industry, the more pernicious and deadly has it shown itself to morality, to religion and even to the very decencies of human society.” For their prejudiced and unscientific opinions Adler denounces the academic investigators as a menace to society; but there is hardly an error he reproaches in them which cannot be found in the Latin emanation from the Holy Father. “Every one knows what damage is done to the soul by bad motion pictures. They are occasions of sin…they show life under a false light; they cloud ideals…” The appeal to morals in the papal encyclical is not criticized in the same language as the corresponding appeal in non-Catholic writers; it is simply characterized as a bit of papal Platonism and therefore within the great perennial tradition. And in rejecting “science” as of any use in the problem Adler can say without irony: “the appeal to science is notably absent from the writings of Pope Pius XI on the problem of the motion pictures.”

To establish the unity of Aristotle, Thomas and Christian tradition as a whole, Adler must resort to a doubtful manipulation of texts. Plato and Paul are equated as rationalists, and Aristotle’s assertion of the animal nature of man is regarded as an anticipation of the Christian doctrine of original sin, as if Aristotle understood man’s animality to be a corruption of a higher human nature and as if this animal nature (contrary to Thomas) was implanted in man after the Fall. With a similar license Aristotle, who used the term catharsis metaphorically to designate the homoeopathic relief of overcharged feelings through tragic drama and certain kinds of exciting music (and in his Politics explicitly distinguished these arts from others), is interpreted by Adler to mean that all arts, in fact all recreation and amusements, have a cathartic function and that catharsis is identical with what Freud describes as sublimation. Even sports and parades are included, and Adler is compelled by his theory to consider these as forms of imitation, like tragedy, as if card-games and fishing were representations of action and as if the architecture of church buildings were designed for the amusement of the faithful. Having elastically deformed the sense of Aristotle in this way, he stretches the rare and unexplicit remarks of Thomas on the value of play and relaxation after labor to mean the purgation of the passions through contemplation of spectacles of human action.

It is by such laxities of scholarship and by such misinterpretations that Adler tries to establish his perennial philosophy and give to his views of the film the dignity of a continuous tradition accepted by the greatest minds, yet accepted because of its self-evident first principles. True, he tells us that his task is not the philologist’s of determining the precise meaning of texts, that he makes the interpretations which these texts permit, but it is not evident on what grounds he believes that the texts permit them or that his selection of texts is appropriate. Reading him, an innocent person must assume that Adler as a Catholic is representing the perennial Catholic position, that if he admits some differences within the church on these matters, nevertheless they are resolved in the official view. But how does he do this? By having Thomas answer Bossuet, although he is compelled to say in a note that Bossuet can in fact cite a lengthy opinion of Thomas favorable to his own position. But Adler is led to downright misstatements of history since he limits himself to a few writers and neglects Christian practice as distinct from Christian philosophers. Thus he maintains that the church has never thought to regulate the recreations of the people, when it is notorious that for centuries its councils and penitentials have pronounced against dancing and popular singing, even in religious festivals.5 The tradition of censorship in the West has been Catholic, whatever Adler may say to throw the burden of fault on Protestants, Platonists and social scientists.

VI. Art and Prudence

In spite of this Christian harmony of art and prudence in the Middle Ages, Adler speaks of the conflict of art and prudence as “inevitable,” and pretends that this inevitability was recognized by the scholastic philosophers. For the scholastics, however, art is simply good workmanship and prudence is counsel or deliberation with respect to a choice in action. For them to speak of an inherent conflict of art and prudence would be like speaking to-day of a conflict between skill and foresight. Nor did the scholastics conceive of the fine arts in Adler’s sense as liberal arts—the artist conveying knowledge of his soul or mind (an expressionistic view entirely foreign to scholasticism and mediaeval practice). For such a distortion of medieval thought Adler must depend on the eclectic Maritain, rather than on Thomas or Bonaventure. Similarly his notion of the “inviolable autonomy” of the artists, which is one of the theoretical sources of the conflict of art and prudence, is so foreign to the scholastics that it is inconceivable how a Catholic scholar could attribute this modern “Protestant error” to the medieval church. The latter thought of the sculptor as an artisan who faithfully carried out the assignments of the church.

If, as Adler says in defense of mediocre and corrupt art, “human society includes all kinds of men and the hierarchy of the arts is responsive to the hierarchy of needs,” it is even more difficult to understand why there should be a conflict between art and morals. He distinguishes elsewhere, it is true, between moral and artistic needs. Against those who condemn a work of art as immoral he insists that the goodness of art must not be confused with morals; and against those who refuse to consider the consequences of art for morality he argues that morality is superior to art. But after having taken such pains to distinguish moral from aesthetic criticism, the first being called extrinsic and the other intrinsic, and after having bludgeoned several innocent writers for neglecting this distinction, he concludes towards the end of his book that the two criticisms are finally inseparable, that “both moral and technical criteria inevitably enter into the intrinsic criticism of works of fine art. They are only analytically separable, as the soul of the artist and his art are analytically separable as principal and instrumental causes of the work done.” It is not made clear why the two should be inseparable nor why the separation should be “important for the sake of clarity” if it leads to confusions.

As a Catholic Adler must make moral values central in the conception of a work of art. His assertion of the superiority of medieval art (Dante and the cathedrals) could not be supported on the basis of technical or formal excellence alone. The greatness of a work varies as the goodness of its subject matter, presupposing, of course, its technical perfection. But this conception of the content lies finally in the moral values of the artist, since he is representing human actions and moral problems. The moral values are judged by an eternal morality, a morality independent of particular social conditions. On the other hand, an artist who deals with contemporary social experience from the viewpoint of a single group is not dealing with moral problems; according to Adler he is dealing with irrelevant “sociological” matter and is bound to produce bad art. If some Russian films, like “Potemkin,” are good it is in spite of their “alien burden of propaganda and sociology.” He forgets here his principle that contemporary moralities are only local determinations of the eternal moral laws—the moral values in “Potemkin” were those accepted by the community in which it was produced—and that moral and technical criteria are inseparable. The conflicts that arise from the desire of human beings for freedom and well-being cease to be human actions and moral problems for Adler once they are tainted with contemporaneity; they become an alien burden of propaganda and sociology. (Since he calls openly for the extermination of sociologists, in fact of all teachers who are not “trained” in his metaphysics, we can imagine what “prudence” supported by state power would prescribe for the inviolably autonomous art with an “alien burden.”) This is the church view; but this view would have excluded the Divine Comedy, the Evangiles and even the Old Testament, which abounds in theocratic propaganda and partisan reference to momentary conflicts. Following Maritain, Adler says that the artist should “express himself fully”—provided he has no interest in the present and is fully orthodox in his social convictions. If he happens to hold radical views he cannot be a good artist, as a priori demonstration from first principles shows.

Adler’s concern for the liberty of the artist is positively touching. But in the particular context of the book the “inviolable autonomy” of the artist is nothing other than the right of the movie industry to produce the films which are profitable to it. If the Catholic church has attacked the movies, Adler comes forward to assure the owners that the church alone respects their inviolable autonomy as producers of the greatest modern art, that Catholic doctrine resolutely denounces those liberal and radical busy-bodies who wish to see films with a morality not accepted by “society,” but the movies ought to conform to Christian morality for the sake of art as well as decency, since technical and moral criteria are inseparable. The church will not dictate what should be made or how it should be made, but rather “what shall be received and by whom and under what conditions.” In this alliance against sin Hollywood and Rome represent the eternal interests of art and prudence. The producers need not, of course, imperil their investment by trying to turn out masterpieces; just as superstitions are necessary to keep the ignorant contented, so there must be films “proportioned” to their lower intelligence and needs. The people require a purgative as well as an opiate; the films which effect this purgation are indispensable to social stability. But the dose must be properly proportioned, according to the rules of morals and art supplied by the perennial tradition. Hollywood has in its own self-imposed code adequate criteria of moral propriety which assure conformity with customs and the maintenance of the existing order. If conflicts and uncertainties remain, Adler reminds us that only a perfected Christian wisdom can solve them, and then “only in ideal terms—the ideal of a supernatural perfection healing the wound of intellect divided against will…Christian wisdom alone can completely reconcile Art and Prudence, since it is endowed with the outlook of Good and ranges over Action and Making alike.” It can also reconcile these moral pretensions with an open indifference to, and even defense of, actual miseries. What shall we say of a moralist who at one point quotes with pietistic unctuousness the phrase of Léon Bloy on the pitiable state of those who do not even wish to become saints, and at another announces that God doesn’t expect all of us to become saints, that we are not all capable of the highest Christian virtue? The priggishness of the book is so evident that even the author feels compelled on his last pages to apologize, but not to prune his moralizing and fulminations. In dealing with such serious matters, he tells us, one cannot help being so solemn and insistent on virtue. But all the incense to moral goodness cannot overcome the stale odor of these old and self-contradicted arguments of reaction.

NOTES

1. Mortimer J. Adler, Art and Prudence (New York 1937, 686 pages, $5.).

2. Reviewed by Abraham Edel, Marxist Quarterly, 1937, pp. 324-27.

3. His remarks on obscenity are a case in point. He argues (1) that the “intrinsic evil of obscenity is not a question of fact but a moral principle,” irrespective of how our idea of what is obscene may change and “regardless of its effects”; (2) that sexual taboos are universal and (3) that obscenity is wrong because it arouses sensuality and sensuality is “morally condemned.” In accord with these principles the naked Eve in the churches of the Middle Ages is regarded as moral, but the naked Venus of the Renaissance as obscene.

4. Concurrent with this profundity, and a symptom of his final solidarity with the lowest levels of the social sciences that he takes such pains to denounce as unscientific, is Professor Adler’s opinion that “what the communists call wage-slavery is consistent with democracy in so far as it depends upon an equality of economic opportunity which is proportional to the abilities of different men.” The Catholic Church is against capitalism “in so far” as it exploits the worker, and against socialism “in so far” as it excludes the capitalist.

5. See Dom. Gougaud, Revue d’Histoire Ecclésiastique, 1914.

Marxist Quarterly was published by the American Marxist Association with Lewis Corey (Louis C. Fraina) as managing editor and sought to create a serious non-Communist Party discussion vehicle with long-form analytical content. Only lasting three issues during 1937.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/marxism-today_october-december-1937_1_3/marxism-today_october-december-1937_1_3.pdf