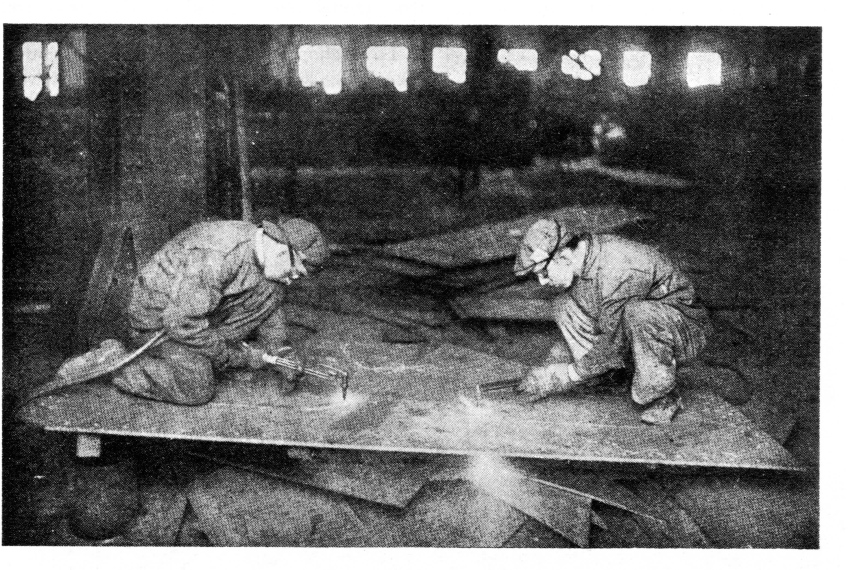

Parts of workers’ bodies are literally pressed into steel at Cleveland’s Midland factory.

‘Hurling Steel 12 Hours Daily’ by Sol Auerbach from Labor Defender. Vol. 4 No. 9. September, 1929.

MACHINES grind, steel bangs, cranes roll along, hammers swing, riveters play their steel song making the din of a steel products plant. Machines grind not only steel here, but also workers’ flesh and blood. Many 12-hour shifts have been sweated into the steel. Many arms, fingers and feet have been impressed into the steel. This is the Midland Steel Products Corporation plant in Cleveland.

Every worker of any standing in Cleveland knows Midland. He knows it as the place to keep away from. He knows it as a slave pen and butcher shop. Not that the other plants are much better. Midland is only a little worse.

Yet, over a thousand men work in Midland, most of us as laborers. There are but few skilled workers here. All of us, Negro, Mexican, Hungarian, Slav, American work on the lines, shoving a frame into a rivet machine, or hammering a few rivets into a frame, or hurling tons of steel on the pile. All the operations here require strength.

A nine-hour whistle blows at 4:30 P.M. That is only the signal for the straw boss to come around and yell into your ear, with a smile on his jaws and furtive look in his eyes, “We’re working to 6 tonight, boys.”

Overtime. It takes your bones and warps them. It makes you flop into bed as soon as you come home. Twelve hours of steady work in a metal plant, flinging steel frames, every motion requiring strength, day after day, kills you. Not only 12 hours of work, but every minute full of speed, every minute a steel frame bumping you from behind into action. Chaotic, frenzied work, rubbing elbows with toilers on every side.

The line must stop for nothing. Midland Steel must increase its profits 100 percent in 1929. It is taking its wallop at the prosperity which gave the stockholders of the United States Steel Corporation $132,100,842 for the first six months of 1929. So Midland has put three lines in the same space as was formerly occupied by one freight-car door line. It cut down on the number of “hands” to a minimum. It worked out an efficient system for reducing wages without the workers knowing it and increasing speed-up.

The promises of piece-work rates do the trick for the Midland bosses. If you work on the repair gang on the Ford truck frame line, pulling the heavy end of a steel frame. from one bench to another and then onto the pile, always on the run, you are promised $1.08 for every hundred frames the inspector passes. Running at full speed, not stopping for a drink or a rest, you can handle 400 frames in 9 hours. That means $4.32 for the 9-hour day. Another 2 or 3 hours work and your pay-check will be 75 cents more. If you work an average of 11 hours a day and 9 hours on Saturday you can figure on a week’s pay of about $27.50. But Midland does not give you the privilege of slaving 11 hours a day for more than two weeks at a stretch. Then there come days of idleness when all that was gained by killing oneself at overtime is more than lost twice over.

Due to the complicated jumble of piece and day rates on all jobs, you are left so much in the dark, that calculate as much as you might, you will not guess what is coming to you at the end of the two week pay period.

For the forging plants, machine shops and metal plants in the state of Ohio, the average hourly wage for unskilled labor is reported to be 31 cents per hour by state statistics. Most of the labor in these mills is unskilled. Picture the lives of the tens of thousands of steel and metal workers in the state.

Overtime, piece-work, speed-up, cutting the number of workers–it is by these methods that prosperity in the steel industry is created.

A steel plant is a battlefield. Stretchers are in place ready for use. The doctor always has his implements ready. It is cheaper to pay for a doctor and for a few dozen stretchers than for safety guards on the machines. At Midland Steel not a day passes when a finger, a foot, or an arm is not squashed into the frames that make the new luxurious Studebaker sedans.

This is the record for four days, including only those instances which I saw myself:

Monday: A young worker, about 18, rushed by the repair gang on the Ford truck frames, holding his arm, leaving a stream of blood behind him. The foremen signaled that 2 fingers, young and straight, had been left in a punch press. The line keeps on working. Tuesday: A stretcher, bearing a limp mass, is stealthily stolen out of the shop thru the rear past the hot riveting machine where I am working. A whole arm caught on a huge punch press on the freight-car door line. Wednesday: Machine repeats while oiler is at work. A foot is left in the steel. Thursday: A machinist loses a foot while repairing a press.

In all cases the line keeps on working. In all cases the workers are restless and mumble but are forced to keep on working. If they leave they are fired. And what of the innumerable bruises, cuts and bumps that color your body with the red, white and blue of Yankee profits? Watch the men as they go in to work and you will see hands without fingers, scars, limps. No safety guards on the machines. Where safety devises exist the foreman will tell you not to use them for it takes too much time. The line must go on and it must turn out its allotted number of pieces, or the scheduled profit promised by the company will not be achieved.

And what of the workers? Do they submit? No one can tell them anything about their conditions. They know them only too well. Long hours, hard labor, low pay, speed-up, lost limbs, are good lessons in class struggle. A shop paper issued by a Communist group in Midland Steel was pasted on the walls of the factory and in the toilets by the workers. The road of action has been pointed out to them. They talk strike every day, they are only waiting for a determined call. And the workers in the other metal plants in Cleveland, in the steel plants of Youngstown and Canton, in the concentrated metal plants in the Beaver Falls River valley, will also follow.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1929/v04n09-sep-1929-LD.pdf