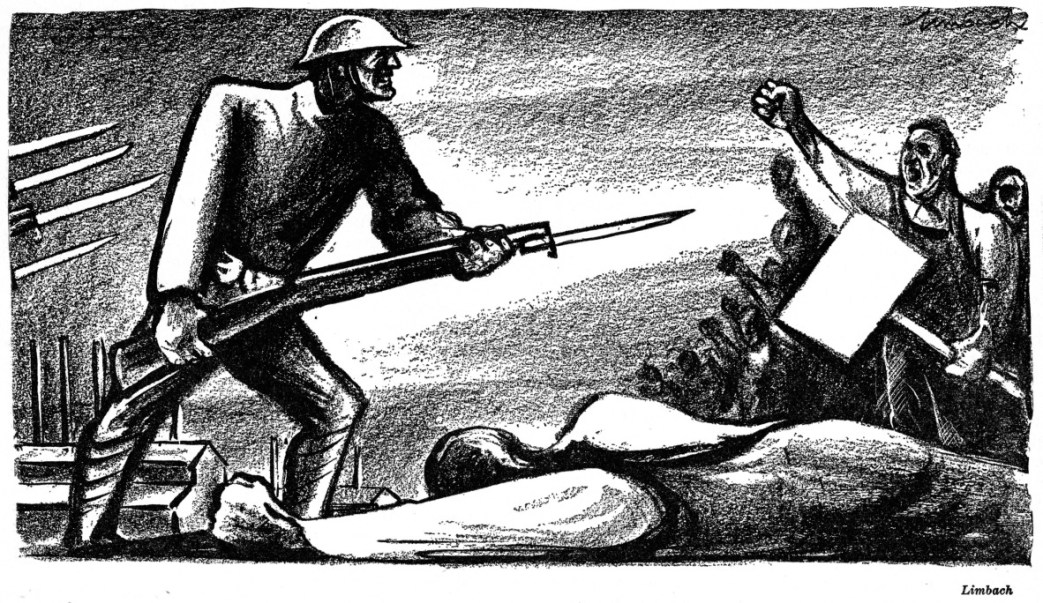

There is a reason that the National Guard were called ‘Father Killers’ in mining communities across the country. Long a force to break strikes and discipline labor, Ben Page looks at its nationalization in the 1930s.

‘Whose National Guard?’ by Ben Page from New Masses. Vol. 14 No. 11. March 12, 1935.

NINE WORKERS were killed by National Guard bullets in labor disputes in the United States, during the nine-month period from January 1 to October 1, 1934.

When the question is posed, “Why do we need the National Guard?” the answer to it is the old army answer, “for defense.” If the United States should send an expeditionary force abroad, as it did in 1917, the reason given would be the same, “for defense.” But from time to time, the highest officials in the army give themselves away.

General Howard, of California, when he recommended the increase in the National Guard strength, stated explicitly, for example, that the civilian forces were for use in the event of “internal disturbances.” Assistant Secretary of War Harry Woodring implied the same thing in the article in MacFadden’s Liberty on the C.C.C. Guardsmen will be called out to protect the scabs, to act as strike-breakers. The best proof that the National Guard will be used for “defense” against American workers is the fact that it has been done and is still being done.

The present administration is openly concentrating the national military forces by increasing the size of the army and navy and creating “industrial mobilization” plans. As a part of this huge war-program, the National Guard has ceased to be primarily a state institution. Without much ballyhoo, quietly and unanimously, the officers of the National Guard have taken the oath of allegiance to the President. Accompanying this significant act, the name of the Guard was changed to “The National Guard of the United States.”

Thus the National Guard of the United States becomes the main auxiliary of the federal army. It might just as well have been recognized as such all the time, since all its pay and equipment is met with federal funds. According to the annual report of the Chief of the National Guard Bureau for 1934, the composition of the National Guard is as follows:

Officers: 13,309

Warrant officers: 198

Enlisted men: 171,284

Total: 184,791

Under the proposed increase this figure will be brought up to about 230,000.

An analysis of the membership of these groups brings to light some very pertinent facts. First, all the higher grades of officers are either wealthy capitalists, leading business or professional men or holders of governmental sinecures (judges, city and state employes in the higher brackets); that is, they all belong to the coupon-clipping groups and they are directly or indirectly tied up with state, city and federal politics of a dubious sort. Second, the lower grades of officers and at least about 5 percent of the enlisted men belong in the category of bank clerks, municipal clerks, laundry-truck drivers, young lawyers, etc. They form a typical lower middle-class following for the officers by whom they are completely controlled, socially and politically. Third, as National Guard units are normally located in centers of population, the majority of the enlisted men are workers. However, the demagogy of the leaders, the subtle persuasion of obedience and fascist discipline, encouraged by War Department agitation, make these workers difficult to approach.

Loyalty to the President, Americanism in its narrowest and most reactionary form, blind discipline–these are the main characteristics desired in an enlisted guardsman. But these men are workers and so it happens that the policy of the National Guard is to use out-of-town troops against local strikers, instead of those stationed in the local armories. The authorities cannot trust the local rank-and-file of the Guard to shoot on crowds of people in whose ranks their own relatives might be fighting. They prefer to have these boys shoot other people’s relatives and bring in other worker-guardsmen to shoot the local citizenry.

The fact that the workers in the ranks of the National Guard obeyed the orders of their officers to kill fellow workers on strike is due to the systematic government propaganda that forms a part of their daily mental ration.

They, as workers, have nothing to gain by obeying these orders; they merely help to fasten the halter of capitalism more securely about their own necks and split the unity of the workers. The Guard itself gives them nothing to brag about. Under the forty-eight-drill system, the guardsman private receives $48 a year plus $14 for his two weeks’ duty in summer camp. However, in 1934 he drilled forty-eight times but was only paid for thirty-six drills, with an additional 15-10-5 percent cut (returned to him piecemeal); he was required to attend the twelve payless drills or be discharged for various unexplained reasons. The guardsman’s total pay-cut for 1934 was 43 percent. Though the pay disbursements dropped, the army appropriations increased tremendously; out of these appropriations the National Guard received increasing allotments for mechanization, in addition to various slices of money from P.W.A. and C.W.A. funds.

The claim has been made that men join the National Guard as a hobby. This may have been the case with many until 1929, but the fact is that today the small quarterly drill pay-checks are eagerly looked forward to by an increasing number. Quite often it was difficult in prosperous times to keep units up to strength; today the precariousness of existence helps to give the National Guard a false prestige as a bread-ticket and accordingly encourages a pro-fascist feeling.

Very recently the chief of staff of the army, General Douglas MacArthur, yielded to the pressure of National Guard officers for an increase in its strength; his support to the National Guard has resulted in a reciprocal support of his army budget both by the National Guard Association and the Reserve Officers Association. This three-cornered alliance of the militarists and pro-fascists maintains a lobby in Washington to fight for bigger armaments. It is, of course, supported by the great munitions firms, by Hearst and the United States Chamber of Commerce.

Opposition is growing in the ranks of the gaurdsmen themselves. Recently, on several occasions, guardsmen have protested against being turned into strike-breakers. In some cases they have mutinied and been withdrawn. Several guardsmen spoke at the Chicago Convention of the League Against War and Fascism; guardsmen in Chicago and New York have made combined protests against intimidating and attacking strikers, against company fund-rackets, uniform-purchasing rackets. Men in the ranks are beginning to realize their position and see through the fog of propaganda to which they are subjected. Sooner or later the guardsmen will learn that they have a common cause with the low-paid white-collar workers, trade union men and unemployed. When that time comes, strikes in the United States will have a different outcome.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v14n11-mar-12-1935-NM.pdf