Nearing on a world he knew well; the vacuum of academia.

‘Academic Mortuaries’ by Scott Nearing from New Masses. Vol. 4 No. 11. April, 1929.

While a social system is young and vigorous it gives youth a chance to spread itself. As it grows old, and approaches dissolution, it builds an institutional structure in which its remains may lie in decent state. American colleges and universities are a part of the mortuary chapel of capitalist imperialism.

Go to an elementary school, among ten or twelve year old boys and girls, and present some idea that is new to supporters of the present social system. The youngsters will examine it; discuss it; react to it—with facile, agile minds. They may agree or differ, but they display signs of mental vigor and life.

Tate a high school junior class next—boys and girls of sixteen or seventeen. Already blase, and mentally “stiff,” they can still react to ideas, but their memories are so clogged with propaganda that they can no longer receive or examine ideas with anything approaching mental freedom.

Now go into a college.

Let me begin by quoting a letter that recently appeared in one of the daily college papers. The writer, a college junior, described “professors, pale-faced, eyes glazed—truly hopeless; students dull, tired, yawning, and chafing at the system they are entangled in.” This is his summary of the tone of American college life.

Here is a letter from a college Sophomore:

“There is a certain manner of procedure in practice which effectually prevents the student body from learning history. At the first session of any history class each student is assigned a topic on which to report, and a book to review. One report is taken up at each session until these peter out and then the book reviews are used to fill in time until examinations bring sweet release.

“Each student who reports copies paragraphs from the reference books, puts them all together and reads the finished product in a hurried monotone. The object is to finish the ordeal as quickly as possible and the class, in co-operation, goes into a deep sleep so as not to disturb the speaker. If one interrupts this routine and asks questions, students and teacher are alike aghast. One doesn’t receive more information anyway because all the student’s knowledge is contained in the paper and there is no recourse but to re-read the paragraph and go on.

“It becomes amusing when a student chooses as references several books of differing points of view. When a paragraph here and there is taken from each one, the result much resembles marble cake, and is as indigestible.

“Perhaps you will understand why next term I study English.”

Many college teachers will retort that this student pictures the worst side of college academic life. I doubt it. The minds of the college students that I meet “feel” as though they had come out of just such a machine.

Recently I sat in a college class in political science where the professor was discussing the question of sovereignty. He explained Hobbs on Sovereignty; Locke on Sovereignty; Montaigne on sovereignty. Eventually he dug his way through the academic rockpile and got down to Dicey.

“Let me test the application of Dicey’s idea to a type of sovereignty such as that existing in a federal form of government Where does sovereignty rest in the United States?”

“In Wall Street,” replied a student.

The professor’s eyelids never trembled; not a glimmer of interest appeared on his face; without displaying even a trace of humor, he lumbered through a heavy explanation of the mechanical workings of the Federal Government.

In another college, where I had a chance to speak to a graduate student group, a young man of twenty, in making an argument to prove the unworkability of Sovietism said:

“In Russia, when a machine is sent into a village, the peasants pull it all apart. One takes a wheel ; another takes some bolts and nuts. That is their idea of property. How can you do anything with such people?”

“How do you get these facts?” I asked him.

“I read them,” he answered.

“And you believe them?”

“Certainly,” he replied.

Obviously he did. He was mentally in the position of a college student who once said to me: “It must be true because it is in the book. If it were not true they would not have printed it.”

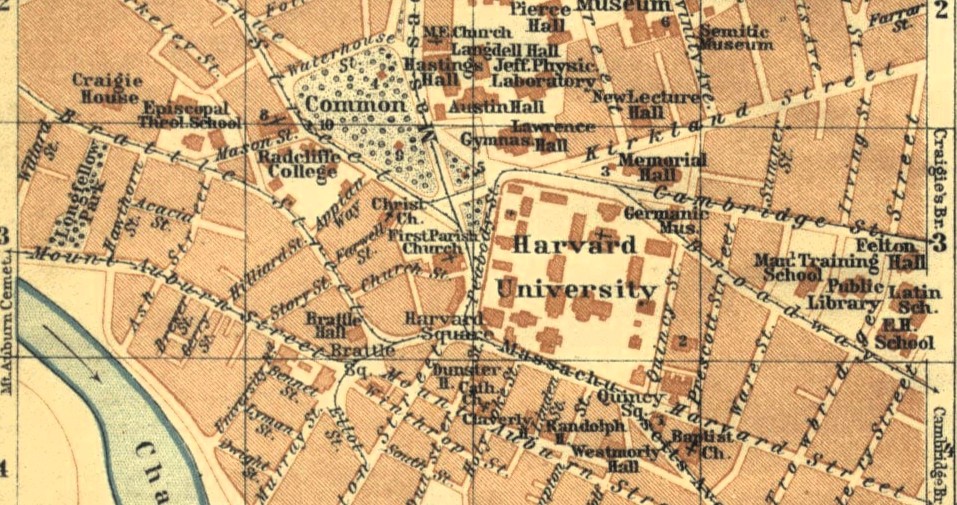

The college students that I meet seem to lack any matured sense of reality. They live in a world of mental make-believe, on a hill, far from the actual struggle of life ; in a social vacuum, where their dolls and teddy-bears are foot-ball games; pool-tables; frats; teas; hops; drinks; smokes. Their nearest approaches to mental reality come in laboratories where they wrestle with the problems of natural science. In the social field they trick and try with “oughts” and “shoulds”; “rights” and other metaphysical concepts while the great world of struggle surges on about the mausoleums in which their youth is being sacrificed to the necessity of pretending that a dying social order is still in the full bloom of youth and vigor.

Are there exceptional students? Of course.

Are there exceptional teachers? Surely.

But the institutions of higher learning in the United States, with their vast endowments; their magnificent buildings; their huge administrative departments; their elaborate curricula are merely one part of a vast tomb which capitalist imperialism in its declining years, is erecting as the Pharaohs of Egypt built the imposing burial chambers in which their mummified bodies were laid to rest.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1929/v04n11-apr-1929-New-Masses.pdf