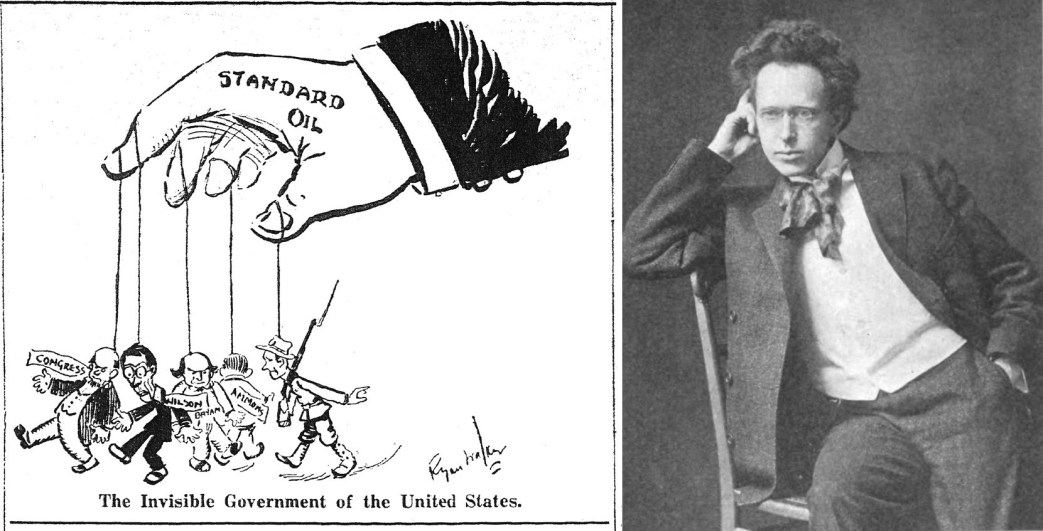

While largely unknown today, every radical of Ryan Walker’s day would have known the work of Walker, revolutionary cartoonist and creator of ‘Henry Dubb’ whose hugely popular, simple proletarian drawings adorned the Appeal to Reason, New York Call, and nearly every other Socialist paper in the country for decades. Born in 1870, he would later join the staff of the Daily Worker and the Communist Party. He died while touring the Soviet Union in 1932 leaving a vast printed legacy. Below are a biography and an appreciation from fellow DW artist Jacob Burck.

‘Ryan Walker’s Life and Work Built Around Struggles of American Labor’ by Jacob Burck from The Daily Worker. Vol. 9 No. 151. June 25, 1932.

Revolutionary Artist Was Known to Thousands of U.S. Workers

BORN at Springfield, Ky., on December 26, 1870, Ryan Walker’s early life was spent on a hilly, rolling farm. His people were of the early English settler stock, with a dash of Scotch and Irish.

Early Talented

At a very early age, Ryan Walker developed the traits which had such a decided influence upon his career. To think for himself and express his own ideas, to read and reach out beyond his narrow environment, to draw pictures on every scrap of paper he could find, and to have a warmth for working folk—the twenty miles from a railroad, in the days before the telephone, radio or automobile.

Ryan’s particular delight was to print with a pencil and draw cartoons for a little newspaper, and his mother used to help him print the words. From his mother, he acquired that fine sympathy and understanding which made him rebel against the hidebound religious bigotry and rotten injustice, which later found a definite expression in his intensity as a Communist.

Studies Art

Ryan went to Texas with his parents. Later his father died and his mother remarried and went to Kansas City. Ryan attended the public schools in Kansas City and then spent two years studying art in New York.

He sold his first political cartoon to “Judge,” when he was sixteen years old. Upon finishing his art schooling, he returned to Kansas City, where he took his first newspaper job with the Kansas City Star. It was on the Kansas City Times, that Ryan’s cartoons began to attract national attention and be copied in publications all over the world. The country was at high pitch over the Bryan-McKinley campaign, and Ryan’s pictures of McKinley as puppet Napoleon on a hobby-horse and Mark Hanna dressed in a dollarmark checked suit created a great demand and many copies were distributed in the campaign.

Ryan then went to the St. Louis Republic and developed the first color section for that paper. His work by this time was well known throughout the newspaper world and he began to get offers to come east. About this time, he married Maud Davis.

Comes East

Ryan came to New York in 1901, and during the following years contributed work to a large number of newspapers and magazines. Later, for three years he was art director of the New York Graphic.

For a number of years he was a regular contributor to the Appeal to Reason, creating the comic strip, “Henry Dubb” which became famous. “Henry Dubb” was reprinted in booklet form and hundreds of thousands of copies were distributed. He illustrated many tracts and booklets which were sent out by thousands. Ryan developed a series of “chalk talks” which went over big with thousands of workers and farmers all over the U.S. and Canada. These talks were very popular and rolled up thousands of subscriptions for the Appeal to Reason. Then Ryan devoted his efforts to the New York Call, before the left wing split in 1919.

The Truth Seeker printed many of Ryan’s cartoons and he illustrated a booklet for them entitled “Funny Bible Stories” which was widely circulated.

While Ryan had no children of his own he was very fond of children. He used to have great fun in mill and mining towns, drawing little “Henry Dubb” sketches for crowds of children who would gather about him. The frightful condition of children in these towns touched him very deeply, and stirred him to greater activity.

Joins Communist Party.

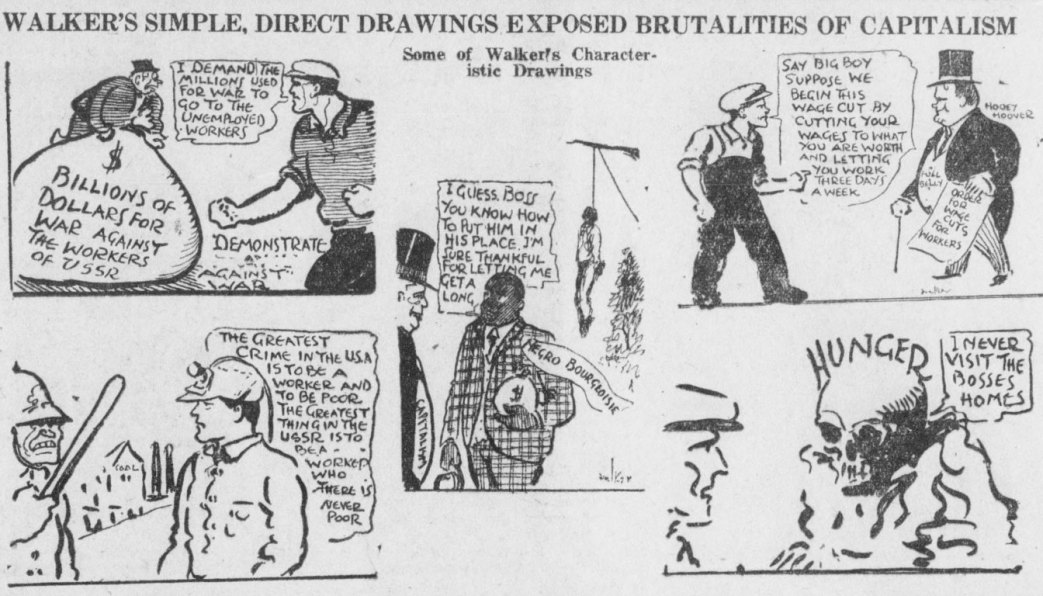

In the autumn of 1930, after several years of isolation from the revolutionary movement, Walker joined the Communist Party of the United States. Several months previously he had already come to the Daily Worker as one of its staff artists. With characteristic fervor and enthusiasm, he threw himself into his work, creating the new character “Bill Worker” which became known to thousands of miners, farmers and workers in the shops and mills.

Loved by Children.

His juvenile characters “Red Pepper” and “Joe, Jr.” were especially loved by the children, and the Young Pioneers of the country claimed Ryan Walker as their own. At this time, too, his “chalk talks” again were in great demand among the workers.

Will Be Remembered.

Ryan Walker will live in the hearts of the workers, and particularly those who knew him. He had a most lovable and charming personality. He was unselfish, and a loyal fighter in the ranks of the working class. His visit to the Soviet Union, though being then quite ill, was the crowning adventure of his eventful career, he had travelled 16,000 miles over the U.S.S.R, seeing the great work of Socialism and glorying in the realization of his dream, the triumph of the workers.

A Co-Worker Writes About Ryan Walker

Jacob Burck, “Daily” Staff Artist, Tells of His Day-to-Day Work With Him

IN THE rush of daily struggle we do not always stop to think of the qualities of those working with us. The death of a comrade brings home sharply what we have lost. In the last couple of years of acute strife, many of our comrades have fallen on picket lines, in protest demonstrations ana on the no-man’s land of the coal barons. RYAN WALKER WOULD HAVE PREFERRED TO HAVE DIED THAT WAY. He was that sort of revolutionist. Instead he daily stuck to his drawing board and sent out his “Bill Worker,” “Red Pepper” and “John Henry” to carry on the fight with those comrades.

Ryan Walker is dead. He died in the Soviet Union, the land where “Bill Worker” rules. Born on a small Kentucky farm in 1870, he grew up with the labor movement which was beginning to assert itself alongside the rise of big industry. He was still in his ’teens when the Haymarket martyrs went to the scaffold.

Thomas Nast was making the Tammany tiger squirm with his savage drawings. Ryan Walker had just begun to draw. There were practically no art schools then in young artists with false grandiose notions removed from actual life. Even if there were, the social consciousness and fire in young Walker could not have been drowned out by fallacious teachings. He was Irish-American— a fighter. His home-spun technique expressed exactly what he felt with no frills or trimmings.

Quite naturally he found himself in the company of other American fighters. Mother Jones, Bill Haywood, Mother Bloor and Eugene Debs. There he found his real function. And so “Henry Dubb,” the strip character known to all old revolutionaries was created and lived for years.

The war was over. The socialist party divided into two camps, the red and the yellow. Things were moving fast. The Soviet Union became an established fact. Ryan Walker found himself in a whirlwind of emotions. Old friendships proved disillusioning, old ideas had to give way to new. Ryan Walker had to readjust himself. He stopped drawing until he could see his way clear again.

The big crash came—1929. The Communist Party organized the big March 6th demonstration against hunger and unemployment. Workers and intellectuals became aware that the Party showed the only way out of this insane, vicious system. The rebellious spirit in Comrade Walker could not be quieted. Almost 60, he decided to cut himself completely off with old friends, and strike out on a new revolutionary road continuing where he left off after the war. He joined the staff of the Daily Worker and was admitted to the Communist Party. It was then that I met him. The surprise was that this peppy, youthful man with a head that resembled very much that of a curly-headed child, was well past middle age.

Walking to Thompson’s for a coffee and hamburger. It was I (less than half his age), who felt the older, hearing him get explosive at seeing a young bootblack chased by a cop—or a young girl slaving away in a restaurant. Like most artists he was extremely emotional, but unlike them he was keenly aware of the sort of world in which he lived. His work showed the same blending of qualities. He was like a mischievous kid running after a person it disliked and taunting him with embarrassing truths—Full-Belly-Hoover, Lord-Cutthe- Dole-Mac-Donald–Hev-Gin-Broun, etc.

His cartoon strips were drawn in his own unique manner. They were carefree, full of spirit, untainted by any art snobbery, uninfluenced by any of the stereotyped technique characterizing most strip artists. They were not “great” drawings according to the standards of the art critics. But they were genuinely part of the man himself. And is more, part and parcel of the lives and struggles of thousands of workers. I say that is real art!

We have lost an artist and fighter. The younger artists who are now working in the movement can learn from Ryan Walker what qualities make working-class art.

JACOB BURCK.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1932/v09-n176-NY-jul-25-1932-DW-LOC.pdf