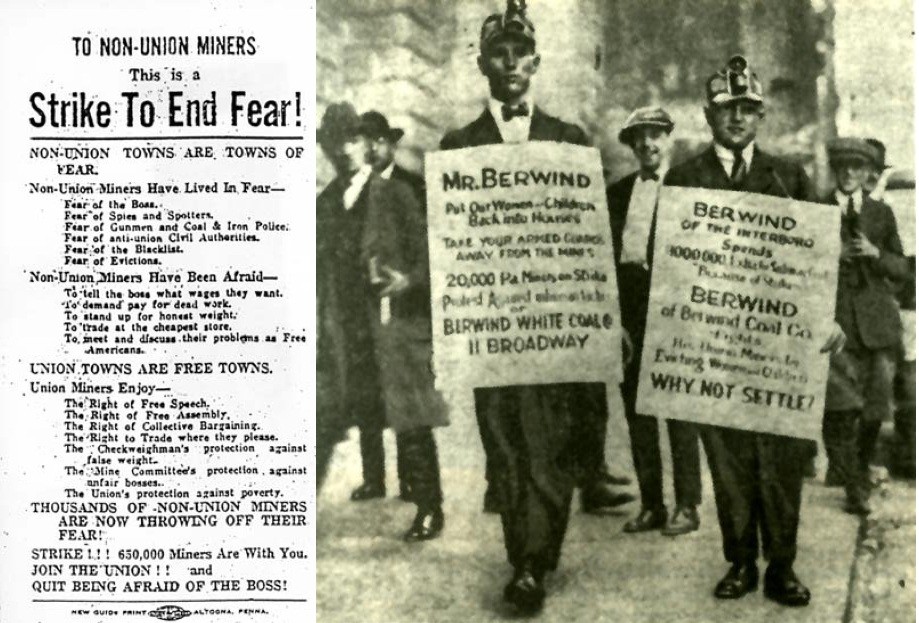

One of the great class battles in U.S. history was the national strike of half a million miners in 1922 against post-war retrenchment. Many of those were non-union miners walking out in solidarity and for a union themselves, only to be betrayed by the U.M.W.A. leadership and left out of the final contracts. Tom Tippett visits the seat of that betrayal, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in an excellent articles on the strike’s aftermath.

‘Aftermath of the Coal Strike’ by Tom Tippett from Truth (Duluth). Vol. 6 No. 8. February 23, 1923.

NOTE. On a visit to the Fayette County, Pennsylvania, soft coal fields Tom Tippett found extreme discouragement and discontent with the miners’ union among the heroic strikers. They had left their nonunion jobs almost a year ago and joined the national strike of the union. Their loyalty was a principal factor in the union victory last August. But they did not share in its fruits and are now suffering the privations of cold and hunger as evicted miners without a job. Tippett explains the situation.

NEW SALEM, Pa.—Van A. Bittner, representing the international executive board, United Mine Workers of America, together with Win. Feeney, international organizer, and Wm. Hynes, subdistrict board member, have put into effect the decision of the international board, calling off the coke region strike in. Fayette county, Pennsylvania. This was done at a delegate meeting of the striking local unions here Jan. 39, 1923. The strike, which at first involved 45,000 coal diggers in this field, had been in effect since the national coal strike called April 1, 1922, The Fayette county field had been under the control of the international organization pending the reorganization of District No. 4, which collapsed with the strike of 1910.

The Executive board of District No. 2 decided, however, Jan. 26, to continue their strike in the nearby Somerset field, called at the same time as the one in Fayette county and maintained under similar conditions. There has arisen here among the Fayette miners and their sympathizers a resentment against the union, which, if ml satisfactorily explained, will prevent organization of the coke mines for years to come.

The coal operators on their part are refusing reemployment to the strikers who apply to their mines for work. Hundreds of families are in dire need of food and clothing. Thousands of little children shiver in their tent or barrack homes, caught in the grip of the steel trust, and neglected by an uncomprehending labor movement in the world outside.

Their story deserves telling, which accounts for this article, put down as it was gathered in the strike zone among the sufferers.

The Surprise of the Strike.

The one surprise in the great 1922 coal strike was the response to the national call by the nonunion coal diggers of the country who downed tools and joined the strike. Unorganized miners everywhere heeded the call, but nowhere with so much unanimity as in the Pennsylvania fields. For the most part these were employed in the mines owned or controlled by the steel trust or the Rockefeller interests, whose labor record is well known.

The strategic points in the Pennsylvania strike (bituminous field) crystalized in the Somerset field and in the coke region in Fayette county. The mines in the Somerset field are owned largely by the Consolidation Coal Co., a Rockefeller concern. The workers in these mines, who struck last April and joined the miners’ union, came under the jurisdiction of District No. 2, headed by John Brophy, with offices in Cleveland.

The Fayette county mines in the coke region. 40 miles away, belong to the H.C. Frick Coal & Coke Co., and like all other steel interests it has kept its grip on the workers in its mines for the last 20 years. When the miners struck there was no district organization functioning to direct them. Win. Feeney, an international organizer, in cooperation with the executives of District No. 5, in the Pittsburg field, took charge of the strike, pending the reorganization of District No. 4 for the coke region.

Thousands Join Union

In the Somerset field 18.000 unorganized men struck and joined the union April 1. In Fayette county 4 5,000 did likewise. Before the strike the Pittsburgh district had a membership of 15,000; District No. 2 in the Somerset region had 43,000 members.

Working condition in Fayette county at the time of the strike were akin to those which obtain in nonunion mines in West Virginia. They worked until the coke ovens were full, regardless of the length of the shifts. They were paid by the car, not by weight. The mine cars were supposed to hold three tons, and for this amount the digger was paid from 66 to 75 cents. This was the rate for machine work. The solid work rate was $1.19 for three tons. All other non-union conditions prevailed, including the company-owned stores and houses.

Company scrip was not used (the company boasts of this), but orders on the company store were given between paydays. The miners could spend their cash wages, left after the company check-off had been applied, where they pleased, with the tacit understanding that if they did not spend it at the company store they would be discharged from the company’s employment.

In Somerset the conditions were nearly as bad. A typical example of the situation before April 1 in this field can be seen in an incident related to the writer by Power Hapgood, now in charge of a part of the Somerset strike. Hapgood applied for work at Vintondale, a camp that is now on strike, in March. When he alighted from the. train a mounted policeman demanded his business and then directed him to the company offices with instructions to “come back here” after he had applied for work. He was about to be given a job when he asked what the rate for dead work was. For daring to ask whether or not that kind of work was paid for (every union mine has a scale for this work), he was summarily ordered out of the office and driven out of town by the officer on horseback.

All attempts in the past had failed to organize these men, but when the call came in April, with ‘‘‘every coal miner in the country” to back them up, they responded in droves. Thousands of them had to wait from one to three weeks to receive the union obligations from the overworked union organizers.

All the methods of opposition, commonly used by bosses in labor disputes, were employed against the new recruits to unionism. In the Fayette field 4000 families had their belongings thrown out of the company-owned houses. Women and children were grossly insulted by company thugs. Many were beaten and thrown into jail. There is no pity shown–women and children by coal barons in this region. Five strikers have been murdered and their murderers allowed to go free by company-owned courts.

No Gamer Bunch Ever Lived.

There is no charge made here from any source against the strikers for violence, he part they played in winning the strike for the miners’ union by told in their organizer, Wm. Feeney, in a printed statement in October, 1922 (after the signing of the Cleveland agreement). It says in part:

“When the history of the great coal strike of 1922 is fairly written there will be outstanding one of the greatest elements that contributed toward bringing together the warring factions, and that will be the tenacious struggle that has been going on in the Connellsville coke region.

“No other factor aided so much in file victory of the miners as did the 50,000 nonunion miners who laid down their tools, joined the United Mine Workers of America and steadfastly refused to be coerced into accepting a few crumbs from the hands of those who for years had owned them body and soul.”

At the same time (October), a subdistrict board member, Wm. Hynes, said also in a statement to the labor press:

“The sixth month of the great coal strike in the Connellsville coke region finds the miners standing solid, but fighting with their backs to the wall and with a spirit that can never be broken and must be seen to be appreciated.

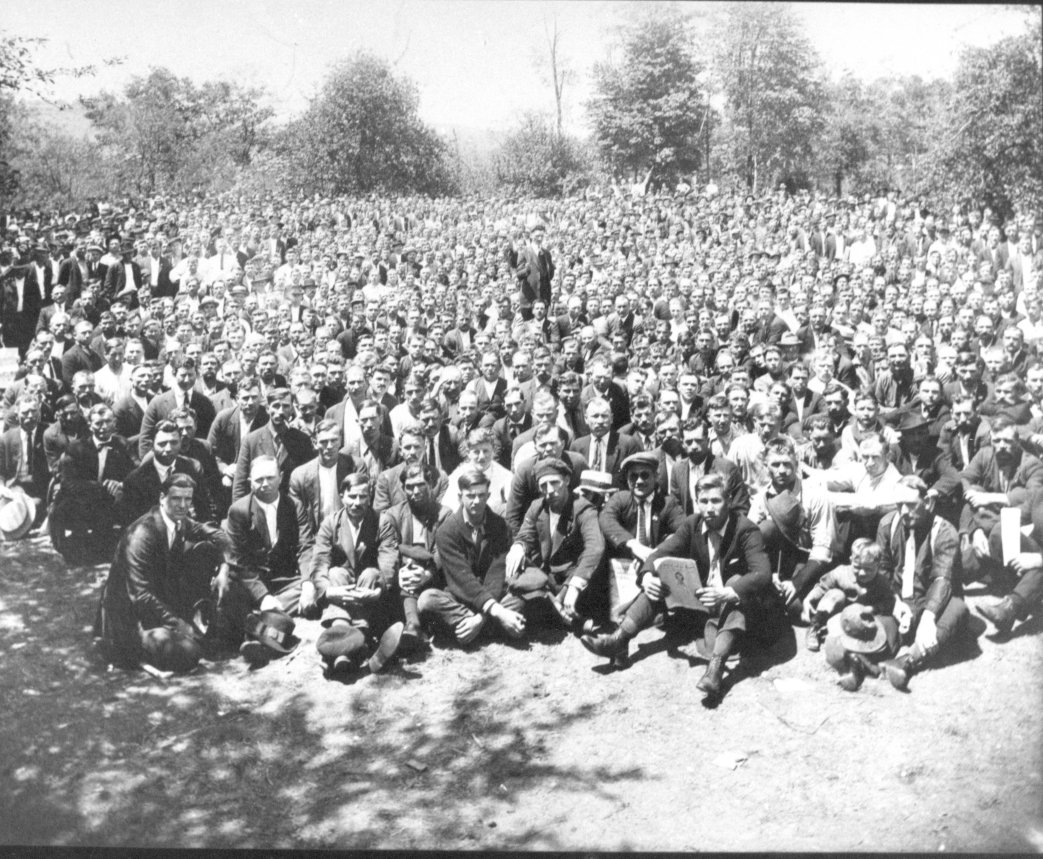

“More than 30.000 of these miners marched in the Labor day parade, Sept. 4, in Uniontown, county seat of Fayette county, where for 30 years there was never a meeting of union miners previous to April 1, 1922.

“On April 1, 1922. the miners of the coke region. 45,000 strong, laid down their tools with their fellow miners and joined the U.M.W.A. About 4000 families have been evicted and these miners bought their own tents. Men have been killed and jailed and mistreated.

“As I write this, their furniture is piled on the fields all over Fayette county. They are sleeping out tonight with their families with the sky for a roof in this rich coal field where they have worked for 30 years to make millionaires and produced the coal that made industrial civilization possible.

“No gamer or nobler bunch of men ever lived. Their strike saved this union beyond the shadows of a doubt. They have paid their debt.”

What the Union Did For Them.

So much for the admitted contribution of these strikers to the national strike victory. What the union has done for them is being debated throughout the country.

The unorganized miners responded to the strike call sent out by the miners’ union because they believed that a strike, national in scope, would entail a national settlement. This was not the position of the union. This article deals with the aftermath of the strike as it affects the Fayette county, Pennsylvania coal diggers who struck with the union miners, but who were not included in the strike settlement.

During the strike union representatives spoke to the effect that “no strike settlement will be made that does not take in the coke region.” Union organizers usually promise more than they can produce to keep up the morale of the strikers.

The Pittsburg Coal Co., reported to be the largest coal producer in the world, is the dominant operator group in District No. 5. This company was not a party to the Cleveland agreement made Aug. 15, and did not sign with the miners until after an unsuccessful attempt to operate one of its mines, known as Montour mine No. 4 at Laurence, 17 miles out of Pittsburgh.

An American flag was set up as part of the open shop plan by which the mine was to he operated. Machine guns and armed guards were established and a call sent out for miners. The coal diggers responded in droves from all over the state. They marched to the mine, saluted the flag and marched away, every man of them. Now pep came into the coke region but not for long.

The Pittsburgh operators signed a contract with District No. 5 Aug. 28. This agreement did not include the Fayette county miners and made it plain to them that they were not to be included in a general settlement. The Somerset county strike was still on, however, and the international union collected a $4 assessment to be used, in part, for the benefit of the strikers. The assessment was collected in November and December. December was the ninth month of the Fayette county strike.

Fayette’s Wounds Will Heal Slowly.

Discouragement turned into resentment when the strikers were notified Jan. 19 that their strike had been called off by the international executive board during the week of Jan. 8. Protest meetings were called. Truths and half-truths, coupled with rumors and falsehoods were hurled into the assemblage of enraged men. I was present at one such meeting in New Salem Jan. 27. The dominant press did not overlook this opportunity to further alienate these men from the cause of unionism. Its stores in bold headlines pointed a “sell out’’ and said that the union had left the coke region strikers “holding the bag,” etc. Hundreds of these papers were in evidence at the meeting which continued in session until night. It was explained that there was no dinner to be had, hence no adjournment was necessary.

Calling off the strike has made no difference in the status of the workers. They are still without jobs, still living in tents and barracks and are still in great need of assistance. They decided at a delegate meeting to return to work, to press no demands but merely seek their old places in the mines. They were ordered out of the company office and told to “go to the union for work.”

When the strike was called off they were told by international representatives that it was done because the union was unable to finance them any longer. They have received benefits since the strike was ended but a union that could not finance their strike will be unable to support the lockout.

There is no strike assessment in effect to finance these workers. The Pittsburgh Miners’ relief, an organization created at a conference of trade unions, fraternal and working class political organizations, is still collecting funds for the coke region but with a strike publicly called off interest dies.

In the Somerset field, District No. 2 is maintaining the strike with a district assessment of $1 per man per week. When the Somerset strike is called off it will be by referendum vote of the membership.

Some strikes must be lost. In industrial war, as in every kind of war, someone pays, but the wounds in Fayette county will heal slowly. The owners of the great steel mills that flare and roar in constant operation I between the coke region and Pittsburgh have won again. The coal larges that have floated uninterruptedly down the Monongahela river from the steel trust mines to the mills in every other coal strike, are not likely to be stopped again for many years.

The Fayette county strikers believe that the 1922 coal strike settlement was a victory for the previously organized miners and that it was made so by reason of their own defeat. They are mistaken about that. The defeat in Fayette county is defeat for every coal digger in the union for, until unorganized mines in Pennsylvania and West Virginia are unionized the United Mine Workers of America is not secure.

Truth emerged from the The Duluth Labor Leader, a weekly English language publication of the Scandinavian local of the Socialist Party in Duluth, Minnesota and began on May Day, 1917 as a Left Wing alternative to the Duluth Labor World. The paper was aligned to both the SP and the IWW leading to the paper being closed down in the first big anti-IWW raids in September, 1917. The paper was reborn as Truth, with the Duluth Scandinavian Socialists joining the Communist Labor Party of America in 1919. Shortly after the editor, Jack Carney, was arrested and convicted of espionage in 1920. Truth continued to publish with a new editor JO Bentall until 1923 as an unofficial paper of the CP.

PDF of full issue: https://www.mnhs.org/newspapers/lccn/sn89081142/1923-02-23/ed-1/seq-1