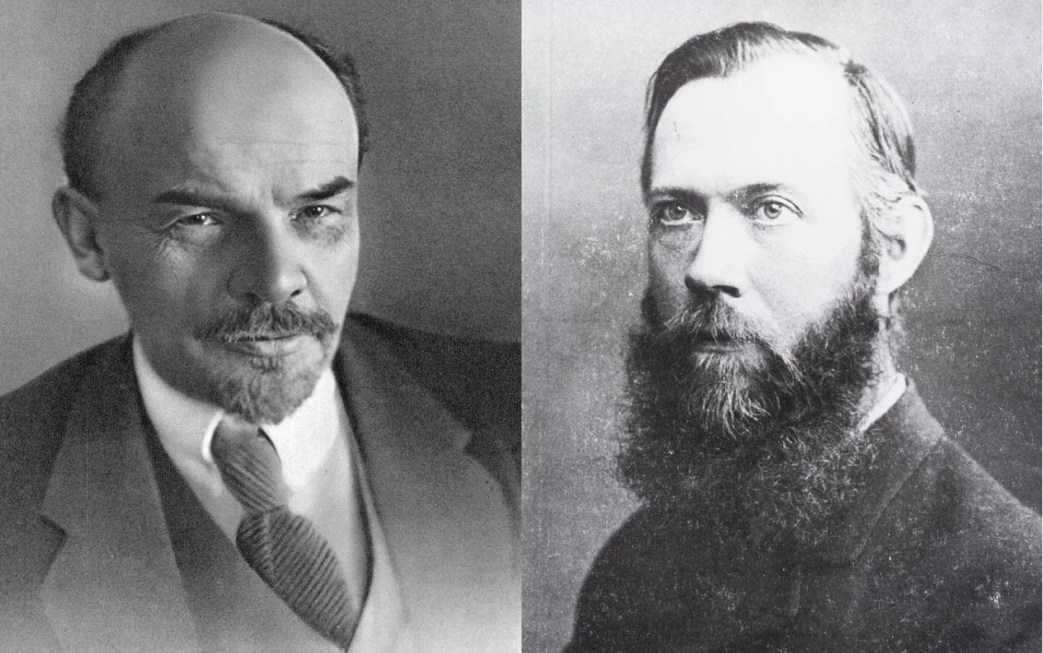

Lenin introduces Russian workers to Anton Pannekoek’s The Tactical Differences in the Labour Movement and its larger lessons.

‘Difference in the European Labour Movement’ (1910) by V.I. Lenin from Selected Works Vol. 11. International Publishers, New York. 1939.

THE principal tactical differences in the present labour movement of Europe and America reduce themselves to a struggle against two big trends that are departing from Marxism, which has in fact become the dominant theory in this movement. These two trends are revisionism (opportunism, reformism) and anarchism (anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-socialism). Both these departures from the Marxist theory that is dominant in the labour movement, and from Marxist tactics, were to be observed in various forms and in various shades in all civilised countries during the course of the more than half-century of history of the mass labour movement.

This fact alone shows that these departures cannot be attributed to accident, or to the mistakes of individuals or groups, or even to the influence of national characteristics and traditions, and so forth, There must be radical causes in the economic system and in the character of the development of all capitalist countries which constantly give rise to these departures. A small book published last year by a Dutch Marxist, Anton Pannekoek, The Tactical Differences in the Labour Movement (Die taktischen Differenzen in der Arbeiterbewegung, Hamburg, Erdmann Dubber, 1909), represents an interesting attempt at a scientific investigation of these causes. In the course of our exposition we shall acquaint the reader with Pannekoek’s conclusions, which it cannot be denied are quite correct.

One of the most profound causes that periodically give rise to differences over tactics is the very growth of the labour movement itself. If this movement is not measured by the criterion of some fantastic ideal, but is regarded as the practical movement of ordinary people, it will be clear that the enlistment of larger and larger numbers of new “recruits,” the enrolment of new strata of the toiling masses, must inevitably be accompanied by waverings in the sphere of theory and tactics, by repetitions of old mistakes, by temporary reversions to antiquated ideas and antiquated methods, and so forth. The labour movement of every country periodically spends a varying amount of energy, attention and time on the “training” of recruits.

Furthermore, the speed of development of capitalism differs in different countries and in different spheres of national economy. Marxism is most easily, rapidly, completely and durably assimilated by the working class and its ideologists where large-scale industry is most developed. Economic relations which are backward, or which lag in their development, constantly lead to the appearance of supporters of the labour movement who master only certain aspects of Marxism, only certain parts of the new world conception, or individual slogans and demands, and are unable to make a determined break with all the traditions of the bourgeois world conception in general and the bourgeois-democratic world conception in particular,

Again, a constant source of differences is the dialectical nature of social development, which proceeds in contradictions and through contradictions, Capitalism is progressive because it destroys the old methods of production and develops productive forces, yet at the same time, at a certain stage of development, it retards the growth of productive forces. It develops, organises, and disciplines the workers—and it crushes, oppresses, leads to degeneration, poverty and so on. Capitalism creates its own gravedigger, it creates itself the elements of a new system, yet at the same time without a “leap” these individual elements change nothing in the general state of affairs and do not affect the rule of capital. Marxism, the theory of dialectical materialism, is able to embrace these contradictions of practical life, of the practical history of capitalism and the labour movement. But needless to say, the masses learn from practical life and not from books, and therefore certain individuals or groups constantly exaggerate, elevate to a one-sided theory, to a one-sided system of tactics, now one and now another feature of capitalist development, now one and now another “lesson” from this development.

Bourgeois ideologists, liberals and democrats, not understanding Marxism, and not understanding the modern labour movement, are constantly leaping from one futile extreme to another. At one time they explain the whole matter by asserting that evil-minded persons are “inciting” class against class—at another they console themselves with the assertion that the workers’ party is “a peaceful party of reform.” Both anarcho-syndicalism and reformism—which seize upon one aspect of the labour movement, which elevate onesidedness to a theory, and which declare such tendencies or features of this movement as constitute a specific peculiarity of a given period, of given conditions of working class activity, to be mutually exclusive—must be regarded as a direct product of this bourgeois world conception and its influence. But real life, real history, includes these different tendencies, just as life and development in nature include both slow evolution and rapid leaps, breaks in continuity,

The revisionists regard as mere phrasemongering all reflections on “leaps” and on the fundamental antithesis between the labour movement and the whole of the old society. They regard reforms as a partial realisation of Socialism. The anarcho-syndicalist rejects “petty work,” especially the utilisation of the parliamentary platform. As a matter of fact, these latter tactics amount to waiting for the “great days” and to an inability to muster the forces which create great events. Both hinder the most important and most essential thing, namely, the concentration of the workers into big, powerful and properly functioning organisations, capable of functioning properly under all circumstances, permeated with the spirit of the class struggle, clearly realising their aims and trained in the true Marxist world conception

We shall here permit ourselves a slight digression and note in parenthesis, so as to avoid possible misunderstanding, that Pannekoek illustrates his analysis exclusively by examples taken from West European history, especially the history of Germany and France, and entirely leaves Russia out of account. If it appears at times that he is hinting at Russia, it is only because the basic tendencies which give rise to definite departures from Marxist tactics are also to be observed in our country, despite the vast difference between Russia and the West in culture, customs, history and economy.

Finally, an extremely important cause producing differences among the participants in the labour movement lies in the changes in tactics of the ruling classes in general, and of the bourgeoisie in particular. If the tactics of the bourgeoisie were always uniform, or at least homogeneous, the working class would rapidly learn to reply to them by tactics also uniform or homogeneous. But as a matter of fact, in every country the bourgeoisie inevitably works out two systems of rule, two methods of fighting for its interests and of retaining its rule, and these methods at times succeed each other and at times are interwoven with each other in various combinations. They are, firstly, the method of force, the method which rejects all concessions to the labour movement, the method of supporting all the old and obsolete institutions, the method of irreconcilably rejecting reforms. Such is the nature of the conservative policy which in Western Europe is becoming less and less a policy of the agrarian classes and more and more one of the varieties of bourgeois policy in general. The second method is the method of “liberalism,” which takes steps towards the development of political rights, towards reforms, concessions and so forth.

The bourgeoisie passes from one method to the other not in accordance with the malicious design of individuals, and not fortuitously, but owing to the fundamental contradictions of its own position. Normal capitalist society cannot develop successfully without a consolidated representative system and without the enjoyment of certain political rights by the population, which is bound to be distinguished by its relatively high “cultural” demands. This demand for a certain minimum of culture is created by the conditions of the capitalist mode of production itself, with its high technique, complexity, flexibility, mobility, rapidity of development of world competition, and so forth. The oscillations in the tactics of the bourgeoisie, the passage from the system of force to the system of apparent concessions, are, consequently, peculiar to the history of all European countries during the last half-century, while, at the same time, various countries chiefly develop the application of one method or the other at definite periods. For instance, England in the ’sixties and ’seventies was a classical country of “liberal” bourgeois policy, Germany in the ’seventies and ’eighties adhered to the method of force, and so on.

When this method prevailed in Germany, a one-sided echo of this system, one of the systems of bourgeois government, was the growth of anarcho-syndicalism, or anarchism, as it was then called, in the labour movement (the “Young” at the beginning of the ‘nineties, Johann Most at the beginning of the ’eighties). When in 1890 the change towards “concessions” took place, this change, as is always the case, proved to be even more dangerous to the labour movement, and gave rise to an equally one-sided echo of bourgeois “reformism”: opportunism in the labour movement.

“The positive and real aim of the liberal policy of the bourgeoisie,” Pannekoek says, “is to mislead the workers, to cause a split in their ranks, to transform their policy into an impotent adjunct of an impotent, always impotent and ephemeral, sham reformism.”

Not infrequently, the bourgeoisie for a certain time achieves its object by a “liberal” policy, which, as Pannekoek justly remarks, is a “more crafty” policy. A part of the workers and a part of their representatives at times allow themselves to be deceived by sham concessions. The revisionists declare the doctrine of the class struggle to be “antiquated,” or begin to conduct a policy which in fact amounts to a renunciation of the class struggle. The zigzags of bourgeois tactics intensify revisionism within the labour movement and not infrequently exacerbate the differences within the labour movement to the pitch of a direct split.

All causes of the kind indicated give rise to differences on questions of tactics within the labour movement and within the proletarian ranks. But there is not and cannot be a Chinese wall between the proletariat and the strata of the petty bourgeoisie contiguous to it, including the peasantry. It is clear that the passing of certain individuals, groups and strata of the petty bourgeoisie into the ranks of the proletariat is bound, in its turn, to give rise to vacillations in the tactics of the latter.

The experience of the labour movement of various countries helps us to understand from the example of concrete practical questions the nature of Marxist tactics; it helps the younger countries to distinguish more clearly the true class significance of the departures from Marxism and to combat these departures more successfully.

December 1910

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/selected-works-vol.-11/Selected%20Works%20-%20Vol.%2011.pdf