Rationalization and automation in the 1930s sparked the ‘disappearance of the working class’ discussion, to which Lewis Corey crunches the numbers and finds a working class still predominate, with conclusions drawn.

‘American Class Relations’ by Lewis Corey (Louis C. Fraina) from Marxist Quarterly. Vol. 1 No. 1. January-March, 1937.

THE APPROACH of fundamental social change makes the problem of classes crucial. An understanding of class interests, consciousness and action is necessary if social change is to become social engineering, animated by awareness of purposes and means. Society is not, moreover, a unity, and no fundamental social change affects all interests alike; progressive interests are fulfilled only as reactionary interests are limited or destroyed. And a multiplicity of minor interests become decisive as they merge into major class interests.

Progressive classes, as they acquire increasing awareness of purposes, means and power, sharply emphasize class interests and the class struggle, identifying their own class aspirations, rightly, with social progress in general. That is precisely what the revolutionary bourgeoisie did.

Conservative and reactionary classes, on the contrary, identify their interests with an ideal “classless” social unity which does not exist and is used to disguise and justify reaction. The triumphant bourgeoisie claimed to represent a democracy in which there were no classes. It is historical necessity that makes fascism, monstrous expression of the most brutal reactionary interests, deny the existence of classes and the class struggle. “How mistaken Marx was,” shouts the bandit Mussolini, “when he claimed that society can be divided into classes, clearly divided and eternally irreconcilable!” Mussolini has “ended” the class struggle by crushing the popular masses and all progressive forces and by diverting Italian aspirations into a madman’s dream of empire—”reconciling” classes in reaction, decay and death. It is, significantly, socialism and communism, whose recognition of classes and the class struggle is basic in their theory and practice, that represent the progressive forces of our age moving toward a new classless civilization.

One of the signs of multiplying social tensions in the United States is the increasing theoretical denial of classes. This is a reversal of the tendency of the more original American historians, during the past thirty years, to apply the class concept to study of our institutional development: an application that, however limited, produced fruitful results. The theory of “no classes” is a retreat to irrationalism and reaction. It is disquieting that many liberals and radicals emphasize the theory; for where the approach to problems of social change is not concrete and realistic, it must promote confusion and reaction.

I. SURVEY OF CHANGES IN AMERICAN CLASS RELATIONS

The “no class” theory emphasizes a classless American democracy. “Classlessness…an attitude hostile to the idea of classes, unwillingness to admit their existence…has been a dominant note throughout American history.”2 That is true, but it is also true that American society has been divided into classes that interpreted the classless ideal in conformity with their own interests. American history is unintelligible unless it evaluates the existence, changes and struggles of classes. Colonial society was marked by an effort to transplant English class relations, including feudal landed estates. The American Revolution was not simply a “national” struggle for independence, considering the hostility of the majority of merchant capitalists, the inner class struggle over democratic rights, the class interests identified with the Federalist reaction. Jacksonian democracy was animated by the struggle for greater rights and power of the farmers, workers and lower middle class. While the Civil War assumed sectional forms, it involved a clash of class interests among Southern slaveowners, Northern capitalists and Western farmers. Nor was Populism a classless affair: it was a struggle of farmers and workers against the magnates of industry and finance. Trade unionism is an expression of class struggle, however limited its purposes and forms. Classless America? Its history is scarred with the struggle of classes.

True, American classes have been extraordinarily mobile and fluid. But that is no proof of classlessness, for the mobility and fluidity are impossible unless classes already exist. In the earlier stages of capitalism, varying according to historical conditions, classes are distinguished by their mobility and fluidity from the status and rank of feudalism; as classes are stratified, and capitalism reacts against its progressive forces, fascism reverts to the feudal ideal of status, rank and hierarchy: the meaning of the totalitarian state…

The classless ideal flowered in the America of the 1820’s-30’s, when class mobility and fluidity were greatest. There were no remnants of feudal relations. The nation was dominated by agriculture, in which the majority (excluding, of course, Negro slaves) were independent propertied farmers, 70% of the gainfully occupied, tenants and laborers being a negligible quantity. The frontier made acquisition of landed property comparatively easy. Industry and trade were in the hands of an urban middle class, 15% of the gainfully occupied, composed of small enterprisers, artisans and craftsmen. Only 15% were industrial or other wage-workers, the industrial revolution having made any real progress only in textiles. Farmers and urban enterprisers constituted 85% of the gainfully occupied. It was a middle class America. A rough economic equalitarianism was created by the widespread ownership of independent productive property. No one expected to remain a propertyless worker.

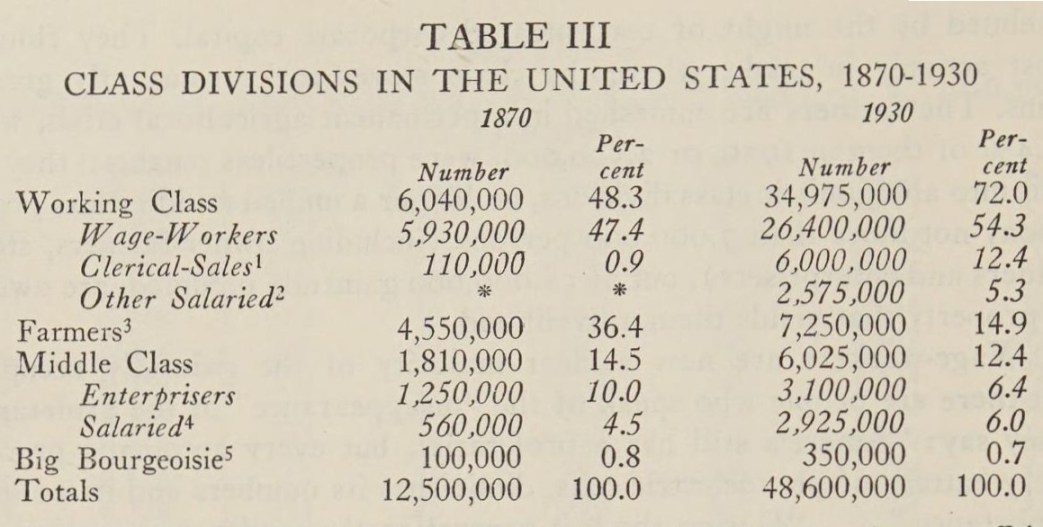

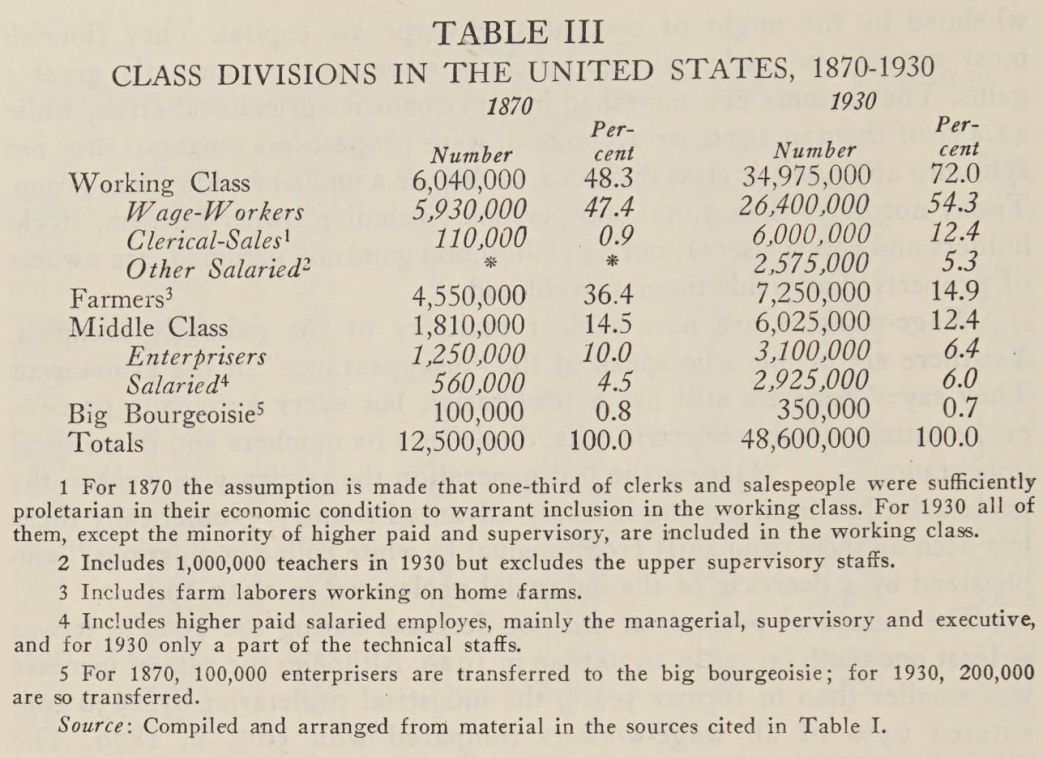

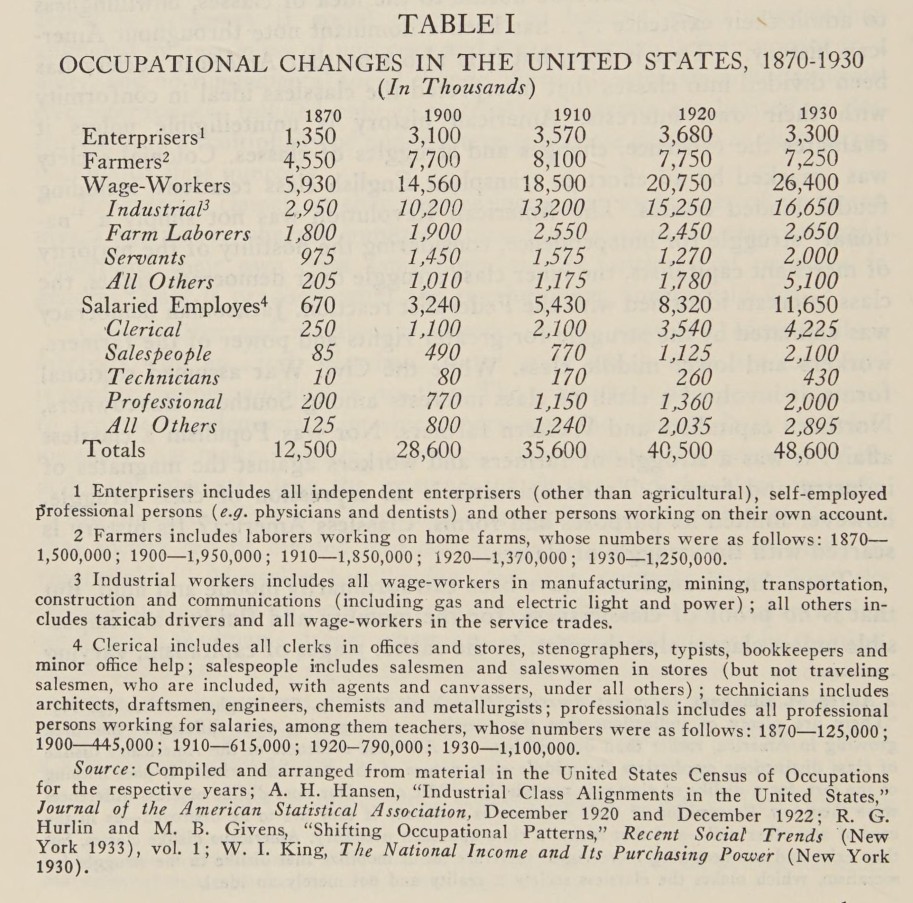

By 1870 all that was changed (Table I). The onsweep of the industrial revolution, and its new technical-economic forms of production, increasingly proletarianized the American people. Now a minority, the farmers included nearly 25% of tenants, while 30% of all persons engaged in agriculture were propertyless laborers. Nearly one-half of the gainfully occupied were propertyless wage-workers. The growth of collective large-scale industry, with its complexity and its separation of ownership from management, was producing a constantly larger class of salaried employees, almost completely propertyless, who performed the managerial and administrative tasks formerly performed by the capitalist owner-manager. The older middle class America was going, and by the 1930’s it was practically gone. The end-product of American “classlessness” was conversion of the majority of the people into propertyless dependents on the property of a small minority and the stratification of classes.

2. AMERICAN CLASS RELATIONS TODAY

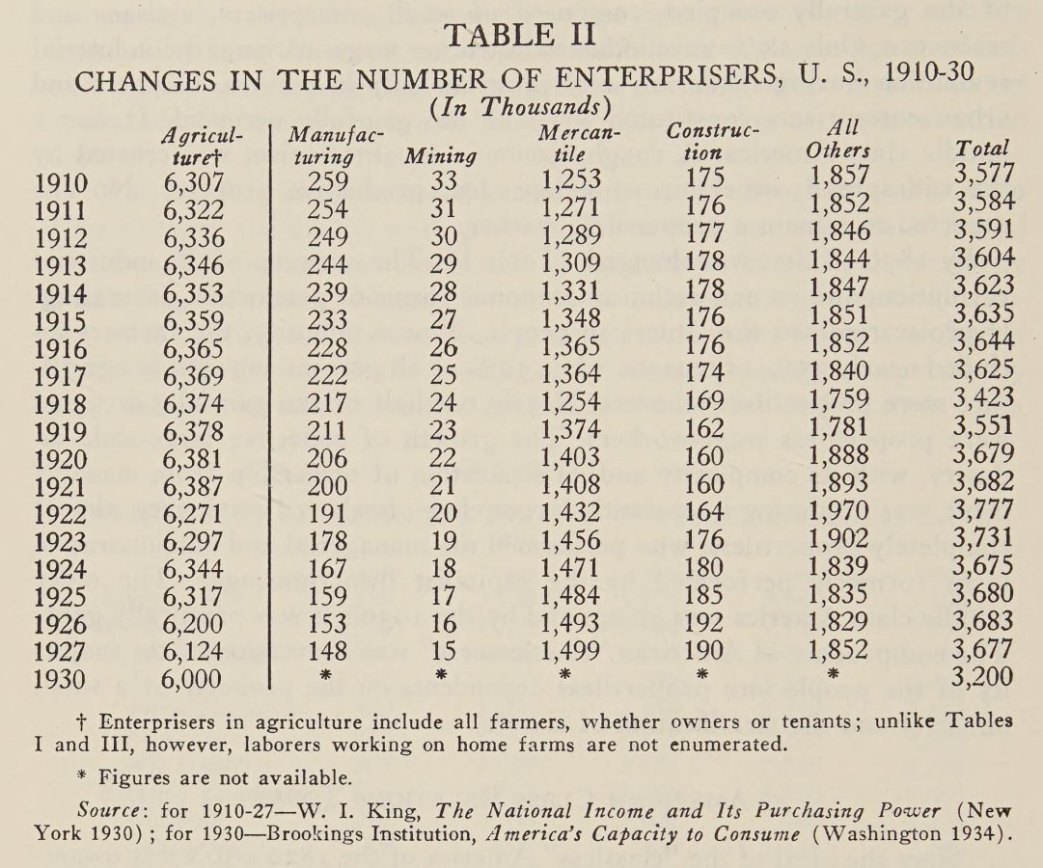

Since the ideal of the “classless” America of the 1820’s-30’s was ownership of independent productive property, it is significant that independent enterprisers today, including farmers, are only 21% of the gainfully occupied, compared with 85% a century ago. The change appears most strikingly in the case of business and professional enterprisers, whose numbers by 1930, despite the increase of industrial activity, were smaller than in 1910.3

That point is important. Up to 1910 the numbers of independent enterprisers mounted steadily, if slowly; thereafter they were practically stationary (Table II). Commenting on his own figures an economist says:

“While the absolute numbers of gainfully occupied, and also the absolute numbers working as employes, have grown steadily larger, the number of entrepreneurs has remained practically constant throughout the two decades [1910-27]…It obviously follows that the percentage of the population classed as entrepreneurs has diminished…It [is] perfectly plain that the independent entrepreneur is playing a relatively much less important role in industry than was the case a score of years ago.”4

There was a considerable decline in the number of independent enterprisers during the depression of the 1930’s,5 but some of the losses have been recovered during the past three years.

The economic power of independent enterprisers is as relatively insignificant as their numbers. Not more than 400,000 are engaged in manufacturing, mining, construction and transportation, where they are overwhelmed by the might of concentrated corporate capital. They flourish most actively in trade, where the chain stores make constantly greater gains. The farmers are enmeshed in a permanent agricultural crisis, while 42.4% of them in 1930, or 2,500,000, were propertyless tenants;6 they are split into antagonistic class divisions, no longer a unified middle class group. Today not more than 7,000,000 persons (including owner-farmers, stockholders and enterprisers) , out of 52,000,000 gainfully occupied, are owners of property that yields them a livelihood.

Wage-workers are now a clear majority of the gainfully occupied. Yet there are people who speak of the “disappearance” of the proletariat. They say: “America still has a proletariat, but every automatic process, every battery of photoelectric cells, diminishes its numbers and its political importance.”…“During the last generation the tendency to weaken the proletariat has been gaining in every advanced country. Numerically there has been an increasing shift from manual to white collar occupations,” emphasized by a decrease of the industrial proletariat in 1919-29.7

The industrial proletariat did not decrease during the 1920’s; it was at least one-tenth larger in 1930 than in 1920. Although the rate of increase was smaller than in former years, the industrial proletariat by 1930 constituted 65% of all wage-workers compared with 50% in 1870. The decrease in the rate of growth was a result of more intensive mechanization, it is true, but it also was a result of the downward movement in the rate of growth of American capitalist industry; hence it marks the beginning, not of the disappearance of the proletariat, but of the decline of American capitalism. To assume disappearance of the proletariat is nonsense: it presupposes a development of technical-economic forces that would strangle capitalism in an unprofitable abundance.

Undoubtedly salaried employes have increased much more rapidly than wage-workers since 1870—a result of the shift from economic individualism to economic collectivism (multiplying managerial and supervisory employes) and the expansion of service industries. But the rate of growth among salaried employes, too, has been decreasing. It reached its peak in 1910; from that year to 1920 the increase in salaried employes fell to 53% and to 40% from 1920 to 1930. Wage-workers, on the contrary, increased more in the later period than in the earlier.

But the increase of salaried employes does not necessarily weaken the working class, although it profoundly alters its composition and creates problems of the utmost importance. For while salaried employes were definitely members of the middle class a century ago and most of them still were in 1870, today the majority of lower salaried employes must be assigned to the working class because of the proletarianization of their economic condition. Security of employment, privileges and differentials in salaries compared with wages have all been undermined. This is particularly true of salespeople and clerical labor. “Only when combined with administrative responsibility is clerical labor well paid…The shadowy line between many of these clerical tasks and unskilled factory occupations is becoming more and more imperceptible.” The prospects of promotion are negligible, while mechanization and scientific management have led “to the virtual elimination of individual initiative.”8 Four out of five professionals are dependent salaried employes and their earnings are comparatively small. Millions of organized skilled workers earn more than the majority of salaried employes: they are no longer separated from one another by a social-economic gulf. The masses of lower salaried employees, who like the workers must sell their labor power, belong to a new proletariat.

The working class, including lower salaried employes, is now an overwhelming majority of the gainfully occupied (Table III). Upper salaried employes, primarily executive, managerial and supervisory, are now the most important part of the middle class, while the big bourgeoisie is a class of predatory financial capitalists performing no useful social-economic function. Middle class America has been transformed economically into a proletarian America prepared for a socialist transformation.9

3. SOME GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Alongside of the effort to prove “classlessness” is the effort to prove that the majority of the American people is middle class—denial of classes becomes an arbitrary regrouping of classes! The following observations are characteristic of that intellectual tendency:

“Already the middle class in America, not including the farmers, outnumbers the working class. Adding farmers to the middle class, the majority in sheer numbers is large.”…“If half the white collar workers be transferred from the proletariat to the middle class and also a fourth of other skilled workers, the middle class would surpass the proletariat. This is a modest estimate of the proportions of these two groups that might be expected to respond to appeals directed to middle class consciousness rather than to appeals directed to the self-consciousness of the proletariat.”…“If the middle classes are taken to include the farmers, professional workers, ‘petty bourgeoisie’ in the strict sense, and white collar workers, the middle classes are at least equal to the working class.”10

But what do they mean by “middle class”? Historically the middle class is a class of independent small enterprisers, owners of productive property from which a livelihood is derived. That includes propertied farmers, but surely not the 2,500,000 tenant farmers who, while they aspire to ownership, are now propertyless. Nor can the middle class include the masses of propertyless, dependent salaried employes, although it may include the upper layers of managerial and supervisory employes whose interests, however, are identified with large corporate capital more than with independent small enterprisers. One may designate salaried employes as a new middle class, but it is a class most of whose members are a new proletariat: a wholly logical economic classification.

It is sheer invention to argue that Marxism recognizes only two classes. Marxism identifies the existence of a number of classes, permanent, transitional and mixed. It is, however, social atomism of the worst sort to speak of a multitude of groups whirling on their independent ways. Many types of groups exist and are important in many respects, but for decisive social action they merge into classes. A class is characterized by its relation to production, its identity of general economic interests, and its relation to the social order, old and new. From that angle the wage-workers and masses of lower salaried employes are united in the working class:

1. They are propertyless dependents in industry and must sell their labor power to live: a proletarian condition.

2. They have the same general economic interests in terms of immediate and final resistance to capitalist exploitation.

3. They are equally the product of economic collectivism (while the middle class of small enterprisers represents an outworn economic individualism), and that collectivism is the objective economic basis of the new social order of socialism.

Within that unity are all the progressive elements of a decisive social change—all the elements of a great mass movement against capitalism, for socialism.

Against that, what is offered? An arbitrary “psychological” regrouping of classes that abandons the concrete, realistic approach to social change. “Psychology is of the essence of classes…We are what we think we are.”11 That is philosophical idealism, which makes objective reality a figment of the human mind—an idealism in which lurk obscurantism and reaction. That people are not conscious of belonging to a class does not make classlessness a fact, any more than a belief in the “Americanism” of J. Pierpont Morgan makes manual workers and salaried employes members of the plutocracy.

The kernel of truth in “psychology is of the essence of classes” involves the problem of class consciousness. That is crucial, as Marxism recognizes, for classes must become conscious of interests, purposes and means to act decisively in the social arena. But classes cannot become conscious unless they objectively exist. The “psychology” argument is used, however, to suggest an acceptance of existing “middle class consciousness” because it cannot be changed: which means abandoning the struggle for a decisive social change incompatible with that consciousness. Nor is it an unchangeable consciousness: it is changing. Fascism changes it in a reactionary sense, for fascist repudiation of democracy and insistence on caste violate all the old libertarian ideals of the middle class. It is changed in a progressive sense when salaried employes form unions, go on strike,12 impose “job control” (which is potential of the final social control of socialism) ; it may be changed by emphasizing that socialism liberates and amplifies the functional services now performed by salaried groups. The problem is to broaden these changes into a socialist transformation of consciousness. Decisive social change involves elements of social engineering: the concrete, sober understanding of forces and interests, of their strength and weakness, of whether they are identified with potential progress or reaction. That is impossible without an understanding of class relations.

NOTES

1. This article is introductory to a series of articles analyzing more fully the historical-theoretical and statistical-occupational aspects of American class relations.

2. Alfred M. Bingham, Insurgent America (New York 1935), p. 92. Bingham writes (p. 94): “There are plenty of indications that the aversion to recognizing class differences has been growing in America, rather than diminishing…All these evidences of the American’s dislike of class distinctions emphasizes the middle class nature of the American mind.” It does nothing of the sort, for a dislike of classes is not wholly middle class. Nor does dislike of class differences wipe them out. Recognition of their existence is necessary if they are to be destroyed—as in the case of any other evil—and that makes a class approach necessary. Americans dislike classes, but they exist and are becoming more rigid: therefore let us mobilize that dislike in the struggle for socialism, which makes the classless society a reality and not merely an ideal.

3. In the National Industrial Conference Board’s publication, National Income and Its Elements (New York 1936), p. 40, Robert B. Martin estimates the number of independent enterprisers for 1930 at 3,825,000. Simon Kuznets, National Income, 1929-32 (New York 1934), p. 11, estimates them at 3,268,000. Alba M. Edwards, of the Bureau of the Census, “A Social Economic Grouping of the Gainful Workers of the United States,” Journal of the American Statistical Association (December 1933), pp. 379-80, estimates “proprietors, managers and officials” at 3,643,000, proprietors alone, it appears, numbering about 2,750,000; adding to proprietors the 500,000 self-employed professionals gives a total of 3,250,000 independent business and professional enterprisers.

4. W.I. King, The National Income and Its Purchasing Power (New York 1930), pp. 52, 64.

5. Kuznets, of. cit., p. 11, indicates a decline of 345,000 from 1929 to 1932 in business and professional enterprisers.

6. United States, Department of Agriculture, Yearbook of Agriculture, 1932 (Washington 1932), p. 492.

7. Stuart Chase, The Economy of Abundance (New York 1930), p. 257; Bingham, of. cit., p. 23.

8. Amy Hewes, “Clerical Occupations,” Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. Il (New York 1930), pp. 552-53.

9. Class relations are roughly similar in England. According to Colin Clark, “Further Data on the National Income,” Economic Journal (September 1934), pp. 385-88, the gainfully occupied are thus divided: Enterprisers, 1,272,000; managerial, 1,180,000; clerical, commercial and professional, 3,698,000; wage-workers (including agricultural), 12,649,000; unemployed, 1,525,000, Industrial workers numbered 7,951,000—exclusive, however, of workers in telephones and telegraphs and in electric light and power.

10. Chase, of. cit., p. 23; A. N. Holcombe, The New Party Politics (New York 1933), p. 101; Bingham, op. cit., p. 56.

11. Bingham, of. cit., p. 17. Bingham argues (p. 27) that universal smoking of the “classless” cigarette and the “equality of clothes” making it “no strange sight to see young workers in a mill town wearing striped flannel trousers, associated a few years ago with Newport,” are “revealing symptoms of the process of social leveling and elimination of class distinctions,” and concludes: “Truly the class struggle may become for many merely an intellectual concept in the face of such significant little facts as these.” Truly a desperate argument! Newspapers report Spanish girls clad in beach pajamas formerly a luxury of the upper classes, fighting against the mercenary hordes of military-clerical-fascist reaction.

12. This is happening with increasing frequency. The New York Times of November 25, 1936 has two suggestive reports: 1) A strike of managers, officials and clerks in nearly all the 100 Schulte stores; 2) licensed ships’ officers strike in Atlantic and Gulf ports and join the ordinary seamen’s picket lines carrying placards and distributing literature.

Marxist Quarterly was published by the American Marxist Association with Lewis Corey (Louis C. Fraina) as managing editor and sought to create a serious non-Communist Party discussion vehicle with long-form analytical content. Only lasting three issues during 1937.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/marxism-today_january-march-1937_1_1/marxism-today_january-march-1937_1_1.pdf