The lives of Black working class women in America; Otto Hall interviews the mothers of the Scottsboro defendants.

‘Scottsboro Mothers, Still Uncowed In Struggle, Fight For Their Boys’ by Otto Hall from the Daily Worker. Vol. 11 Nos. 107 & 109. May 5 & 7, 1934.

“They Shall Not Die!” Cry of Thousands On May Day, Thrills Scottsboro Mothers

This is the first part of an interview with five of the mothers of the nine Scottsboro boys, by Otto Hall. The second part of this interview will be published in Monday’s Daily Worker. These five mothers are going to Washington on May 13, Mothers Day, to see the President, and demand from him the immediate freedom of the nine boys who are being mistreated in the Birmingham jail, and who have been imprisoned for nearly three years, despite overwhelming proof of their innocence. A send-off meeting will be held Friday night, May 11, In St. Nicholas Arena.

“I’m going to Washington to see the President about my boy,” said Mother Ida Norris, when the writer asked her about her intended trip to Washington on Mothers’ Day.

“Do you know.” she said, “that me and my boy Clarence were born in Warm Springs, Georgia, where the President lives in the winter time? Well, we’re going to find out what kind of a deal Mr. Roosevelt gives his home town folks,” she said, very determinedly.

All five of these mothers were born down in “Dear old Georgia.” where the “Honeysuckles Bloom” and “Everything is Peaches,” according to the song writers. Poets can sing, novelists can spin romantic yams, about southern belles, gallant colonels, Negroes singing in the cotton and such tripe, but to see the careworn faces and toil-ridden hands of these mothers, and to hear their stories of a life of hard work and privation, one gets a real picture of that feudal hell, known as the “sunny” South. This is the South stripped of its halo of romance and exposed as one of the most benighted, disease-ridden, poverty-stricken sections of this great United States. Where the Bourbon rulers have made both Negroes and “poor writes” their beasts of burden.

Encouraged by May Day

I found the mothers still talking about the great May Day demonstration, in which they participated, and they told me how encouraged they felt when they heard the tens of thousands of workers pass Union Square shouting: “The Scottsboro boys shall not die.” They told me that they know that the International Labor Defense, which has the support of all those workers, will save their boys.

The stories of these mothers, which in many respects are similar, give an accurate picture of the oppression and enslavement of the Negro nation in the southern “Black Belt.” Nearly all of them came from large families and have had to toil on plantations as sharecroppers or plantation “hands” and went to work at an age when children in more fortunate circumstances were still in nurseries. The average age of these mothers when they “set out to chop cotton” was seven years.

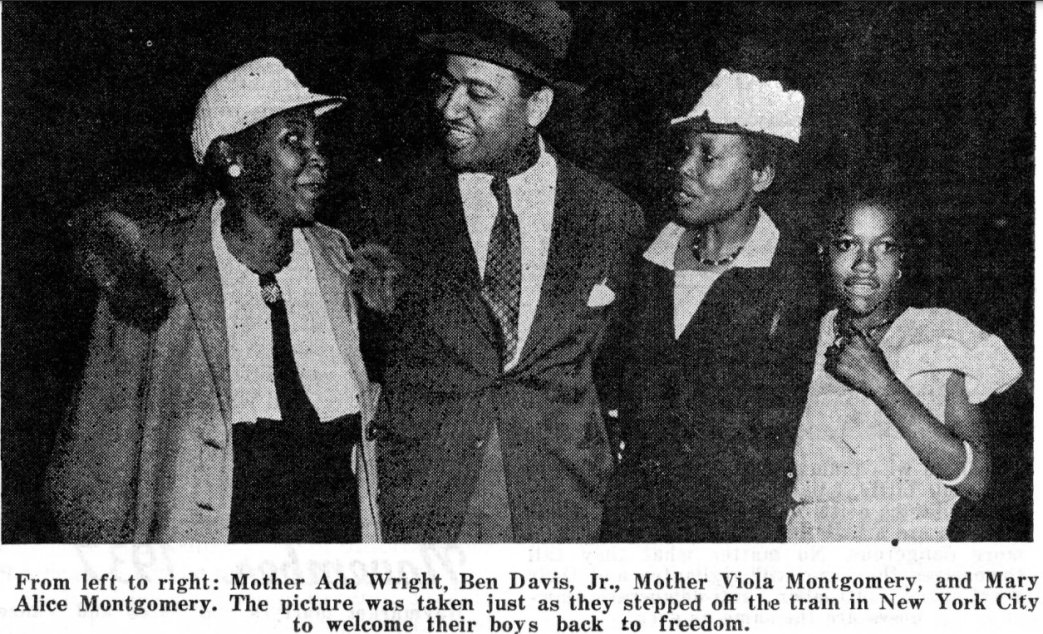

Mother Viola Montgomery says she was about six years old when she started to chop cotton on the plantation of George Felkner, who was the richest plantation owner in Monroe County, Ga., where she was born. She said that she was supposed to have been paid the “liberal” sum of 25c a day for her work at that time, but never saw any money. The “Colonel” said it all went for her “keep.” After she was grown up, she chopped cotton for 65c a day.

Mother Montgomery was born on this plantation 44 years ago and was one of a family of seven girls. The father, a plantation laborer, died when she was very small and all of them were forced to work in the fields from the time they could barely toddle. She married when 15, thinking to escape this slavery, but found that instead of escaping so much toil she had to work even harder than before. She began to have children so fast, she said, that it looked like she hardly got through having one, than she was “big” with another. She was the mother of six, only three of whom are still living. When her boy Olin, who is now in prison, was about four weeks old her husband got into trouble and was sent to the chain gang for a term of years, leaving her to take care of the children. Her oldest daughter died from neglect because she had to toil in the field and couldn’t give her proper care. Because she had to go out and work a few days after Olin was born, she has been in bad health ever since. This is the life of the average Negro toiler in the South.

Olin Supports Family

Her oldest boy married and there was nobody to help the family but Olin, who worked at a boarding house for $3 a week. He told his mother that he was tired of working there and not getting anything for it so he was going to Chattanooga to see if he couldn’t earn more money. Mother Montgomery says that she never saw him any more until she saw him in Kilby prison. Mother Norris, the President’s fellow-townswoman, does not know her age but thinks that she is around 45 or 46 years old. She is the daughter of a sharecropper and as worked since she was seven years old.

She says it seemed as though their family could never get out of debt. The harder they worked, the more they owed. She married at 17, thinking that she would have an easier life but like the others, found she was taking on more trouble and work. She is the mother of 10 children, eight of whom are living and two are dead. She has been a widow for 10 years. She left Warm Springs to get away from the plantation and moved to Moline, Ga., her present home. She took in washing and all of her children had to go to work. Her boy, Clarence Norris, now in prison, was working in a saw-mill for 50 cents a day. He also took a job on a peach farm, picking peaches, but the pay was so small, that he decided to give it up. He told her that he was going away to the North where he could make more money and be better able to take care of her. He said that he “wasn’t going to follow nobody’s mules no more.” He went to Atlanta where he caught the train to Chattanooga.

He never met the other boys until he got on the freight train. She says that she did not see him any more until she saw him in prison.

II.

Mother Powell was born in Sparta, Ga., and was one of a family of ten. Her family, also, were sharecroppers, and she has worked ever since she was old enough to remember. When she was a very little girl, hardly big enough to put her hand on top of the table, she was sent to the “big house” to help in the kitchen. She was so small she had to stand on a box to wipe dishes and iron clothes. A few years later, she was sent to the fields because there were other little children to take her place in the kitchen. At fourteen she plowed with two mules. This was a plenty big enough job for a full grown man.

She was married at the age of 13 to a sharecropper on the same plantation. She had “graduated” into a life time school of misery and hard labor. She is the mother of seven children, and is a widow. Her boy Ozie was only 14-years-old when he was arrested. Like the others he had gone away to get work. He had to help take care of his mother and older sister, who was sick. As a result of the hard work she had to do as a child. Mother Powell’s health has always been poor.

All Are Fighters

I listened to these mothers tell their story and could feel with them a burning indignation against a vicious system that make beasts of burden out of human beings These mothers are all fighters. Suffering, oppression and living in one of the champion lynch states in the country has not cowed them in the least.

Mother Patterson, whose son has been condemned to die three times by the lynch courts, said, “I get so filled up when I think about my boy I can hardly hold myself. My health ain’t been very good, but I’m going to work in the I.L.D till the last breath leaves my body I’m going to make it so that other colored mothers won’t have to go through what I went through.”

Mother Patterson was born in Elberton, Ga. She also comes from a family of sharecroppers. He mother died when she was about seven years old, and she went to work in the fields at that age. She married when she was about 18 she thinks, and is the mother of 11 children. Only six of them are living today. She has gone through a lifetime of miserable toil. Often she worked in the fields while carrying her children up to the day they were born. Her husband, Claude Patterson, is like her, an active fighter in the I.L.D. He has a reputation in his community of being absolutely fearless and is known by the “good” white folk as a “biggity n***r.”

“My husband, Claude, never did take no foolishness off’n white folks,” she told me, proudly, “and Haywood is just like his pa. Ain afraid of nothing or nobody.” She told of the time her husband tried to kill his planter boss, who attempted to cheat him out of his cotton. When the “law” tried to organize a mob to “put this Negro in his place” the planter, fearful of losing a valuable “hand” told the mob not to interfere between him and his “n***rs” because he was able to handle his “n***s” himself.

Patterson was determined to send his children to school and when the planter objected, he moved away with his family to Chattanooga. He told his friends that he was through with ploughing cotton and that even if he only earned a couple of dollars a week in the city he would at least be able to see cash.

In 1931, the year his boy was arrested, he was only making four days a week on his job, and the combined earnings of the whole family was scarcely enough to feed them. Haywood Patterson quit school to go to work because, he told his mother, that he was tired of going to school in overalls.

He said, “I’m big enough to help you and pa out now and I’m going up North where I can make more money.” He said, “Put some starch in my overalls Ma, so that I can look clean when I get there.” “That’s the last I saw of my boy, said Mother Patterson, “til I sa him in jail.”

All of these mothers, in spite of years of toil and bringing many children into the world, are fine looking women. These are working class women and a comparison between them and triple-chinned poodle-dog-following women of the parasite class show the ones who are to survive and who are capable of making the world a fit place in which to live.

Mother Williams, the youngest of the Scottsboro mothers, is only 34 years old and looks even younger. She was born in Atlanta, Ga., and was brought to Chattanooga by her parents when a baby. She went to work at the age of 11, quitting school before finishing the third grade. She married at 14, and the mother of 10 children, seven of whom are living. Her husband died when she was still carrying he youngest baby.

Her boy, Eugene, was only 13 when he was arrested at Scottsboro and charged with rape. When he left he told his mother he was going to Pittsburgh where his uncle lived and that he would soon get work and send her money.

These mothers, in spite of the fact that they have had very little formal education, have plenty of native intelligence. A talk with them blasts the vicious lie spread by Pickens and Walter White of the N.A.A.C.P. that these mothers were ignorant and did not try to bring their children up properly.

According to Du Bois, Schuyler, White, Pickens, Robert Vann of the “Pittsburgh Courier,” and others, these mothers are “ignorant and depraved” because they had too much sense to trust the fate of their boys to these agents of the lynchers. Even today, the leaders of the N.A.A.C.P. are conniving with the Southern lynchers to try to force the boys through torture to repudiate the I.L.D. and let them handle their case. Protests by the thousands must go to Deputy Warden Dan Rogers of Jefferson County jail in Birmingham, Governor Miller, President Roosevelt to stop the torture of these boys.

Workers and those sympathetic should know that the families of these mothers can use children’s clothes and shoes if these are sent to the District I.L.D. office, 87 Broadway.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1934/v11-n108-may-05-1934-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1934/v11-n109-sect-one-may-07-1934-DW-LOC.pdf