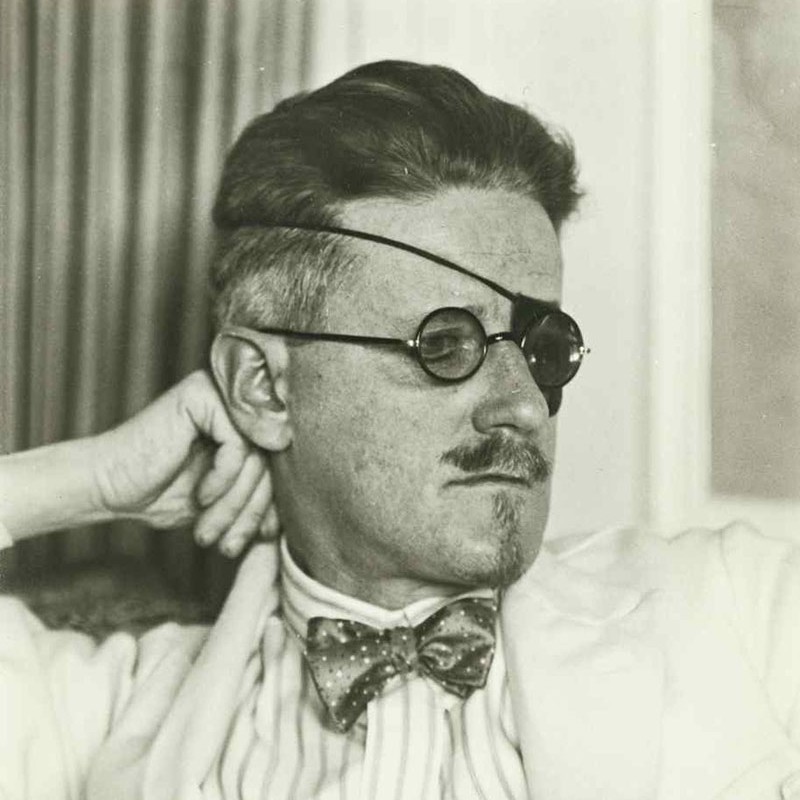

A central literary figure in the 1930s world of New Masses and Partisan Review on what ‘proletarian literature’ learned from James Joyce.

‘The Methods of Joyce’ by Wallace Phelps (William Phillips) from New Masses Vol. 10 No. 8. February 20, 1934.

At this stage in Marxist criticism, the class roots of Ulysses may almost be taken for granted. With the growth of revolutionary literature in America, the really important question about Ulysses is its relation to the methods and sources of revolutionary-proletarian literature.

James Joyce has risen to a new peak in English literature, and he has had a profound influence on contemporary writers. But the most effective part of that influence has been indirect. The school of disciples–centered mainly about transition–who have been experimenting with Joycese have never produced anything of sustained vitality, and they are now fading out in a last flurry of word-capers, which they have ostentatiously named writing of the “vertigral age.”

The demise of Joyce’s disciples proves that the method of any writer, however effective, cannot be transplanted to other literary material, particularly to proletarian material. At most, some aspects of Joyce’s sensibility and innovations in prose form may be assimilated (as Virginia Woolf, Sean O’Faolain, Hemingway, and Faulkner, for instance, have done), but only after the relation of Joyce’s methods to his purpose, his theme, and his sensibility has been recognized. In general, the assimilable elements of Ulysses are few, because the purposes of Joyce are so specialized.

The very existence of guides like Stuart Gilbert’s and Paul Jordan-Smith’s testifies to the detachment of Ulysses as a whole from ordinary human and even literary experience. In A Key to the Ulysses of James Joyce, Smith briefly summarizes the sequence of incidents, and then traces a rough parallel between the situations and characters of Ulysses and those of the Odyssey. He takes issue, though, with Valéry Larbaud, who emphasized the web of symbolism which relates each episode to some technique, color, organ of the body, science, Greek character, Greek myth, etc. “It seems to me,” writes Smith, “that this meticulous analysis adds little to the understanding of the book.” In general, aside from some perfunctory tributes to the depths of Joyce’s insight and the effectiveness of his “vocabulary,” and some objections to occasional overladen word-combinations, Smith avoids broader questions of literary criticism. But the reader of Ulysses will find Smith’s guide very helpful.

Joyce’s characters are probably more complete psychologically than those of any other novelist in the history of literature. A full background of memories and associations is background of memories and associations is woven into the acts and thoughts of Dedalus and the Blooms. This continuity of thought-process underrunning their actions, or stream of consciousness, as it is commonly called, necessarily has been carried through dramatically unimportant as well as important incidents in the lives of the characters. To achieve an intensity of meaning at almost every stroke of the pen, Joyce has introduced two prose forms: a run-on of free association, as in Mrs. Bloom’s soliloquy, giving all the twists of a range of experience, and a use of word clusters, such as “Right and left parallel clanging ringing a double decker and a single deck moved from their railheads, swerved to the down line, glided parallel,” encompassing in a single image a variety of impressions. But, in addition, the prose throughout Ulysses has a remarkable suppleness of idiom which gives a constant sense of recognizable reality to the reader. And the cadence is almost perfectly adjusted to the ring of each situation.

As Robert Cantwell has observed in a recent essay on Joyce, writers have recognized “that under the lens of his methods all the over worked scenes of realistic narrative, like drops of water under a microscope, are suddenly seen to be teeming with unsuspected life; the pauses and silences whose meaning could barely be guessed, the nuances of moods, the emotional guessed, the nuances of moods, the emotional responses which are scarcely reflected in speech or gestures or facial expression–all this, it can be seen now, is packed with infinite voiceless dramas, with dramas which yield less fully to any other method of presentation, or cannot be stated at all.” But these merits have been achieved at the expense of immediate intelligibility to a reader with an average background of experience. By this I do not mean that all great art must be readily understood by the average man. I mean that James Joyce in successfully probing many psychological complexities of modern life has used a method which has detached his characters from significant social patterns. (Robert Cantwell has emphasized the extent to which the Irish revolutionary movement enters into all of Joyce’s writings, but I cannot see that it is any more than a source of memories which rise to consciousness in various parts of Ulysses: the revolutionary movement in no way affects the course of events.) Even time in Ulysses is relative to the thought processes and the acts fulfilling them, rather than to the tempo of the social world. The stream of consciousness follows its own steady course. Consequently, as Edmund Wilson has noted, Ulysses is essentially symphonic, non-dramatic. Joyce’s method could hardly be used to present social conflict or human conflict against a background of class struggle.

Ulysses represents, I believe, the fullest possible exploitation of language for the purposes Joyce has evidently set himself. But there is a limit to the load which language can bear and still remain a medium of communication; and there is a limit to the use to which any literary method can be put if it is not to become sheer method. Though some critics hail the published fragments of Work in Progress as the Ulysses of the dream world, it seems to me that Joyce is crossing these limits. While Joyce is narrowing the social frame of experience, proletarian writers are grounding their themes and forms in the class pattern of life.

However, in that the sensibility of Joyce is an important reaction to the contemporary world, and the technical devices in Ulysses are effective for exploring parts of that world, Ulysses is now part of our literary heritage. And it is likely that proletarian writers will use variants of the Joycean method in some portions of their novels for presenting, for example, a flow of memories, a merging of thought with conversation and action, a sense of multiple meaning in a scene, or, as Dos Passos has done, for relating the lives of diverse characters to a social situation.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1934/v10n08-feb-20-1934-NM.pdf