Sergius Kravchinsky, Stepniak, was born in 1850 and became a leading activist and chronicler of the Narodniks. Among his activities was organizing Kropotkin’s 1876 escape from the Peter and Paul Fortress and the 1879 execution of the Police Director of St. Petersburg. However, his most important contribution was his book ‘Underground Russia’ written in exile of those events. Below, a biography of his comrade Vera Zasulich, who in 1878 shot the Police Prefect Trepov after he ordered the whipping of an imprisoned student.

‘Vera Zasulich: The First Terrorist’ by Stepniak from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 7 No. 2. July 15, 1922.

In the whole range of history it would be difficult and perhaps impossible to find a name which at a bound has risen into such universal and undisputed celebrity.

Absolutely unknown the day before, that name was for months in every mouth, inflaming the generous hearts of the two worlds, and it became a kind of synonym of heroism and sacrifice. The person, however, who was the object of this enthusiasm obstinately shunned fame. She avoided all ovations, and, although it was very soon known that she was already living abroad, where she could openly show herself without any danger, she remained hidden in the crowd, and would never break through her privacy.

In the absence of correct information imagination entered the field. Who was this dazzling and mysterious being? Her numerous admirers asked each other. And every one painted her according to his fancy.

People of gentle and sentimental dispositions pictured her as a poetical young girl, sweet, ecstatic as a Christian martyr, all abnegation, all love.

Those who rather leaned towards Radicalism pictured her as a Nemesis of modem days, with a revolver in one hand, the red flag in the other, and emphatic expression in her mouth; terrible and haughty—the Revolution personified.

Both were profoundly mistaken.

Zasulich has nothing about her of the heroine of a pseudo-Radical tragedy, nor of the ethereal and ecstatic young girl.

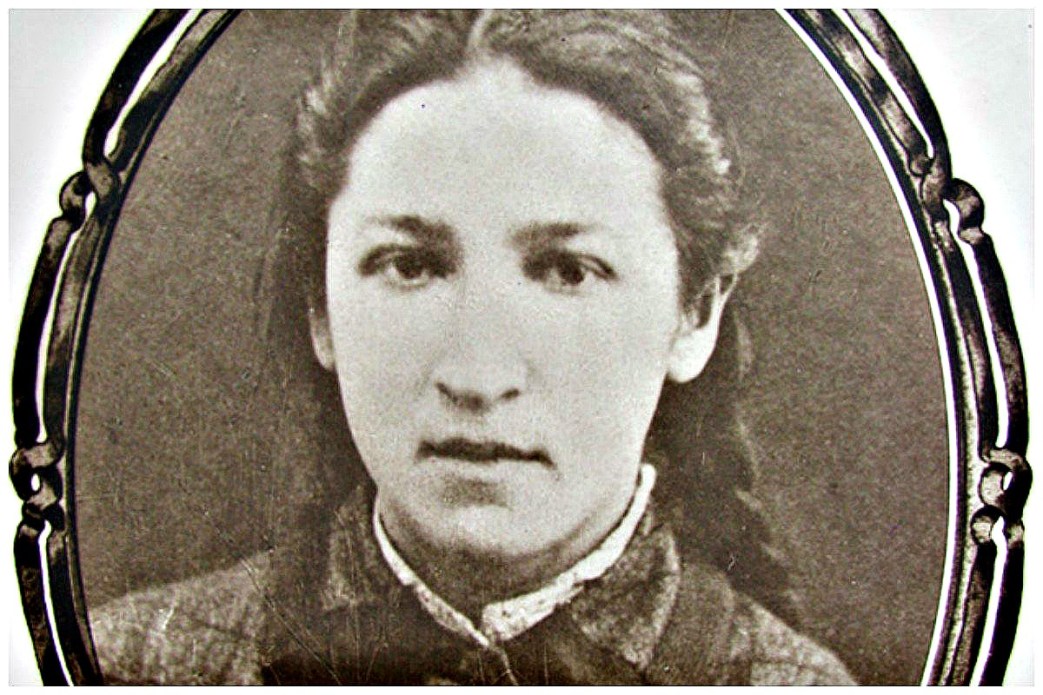

She is a strong, robust woman, and, although of middle height, seems at first sight to be tall. She is not beautiful. Her eyes are very fine, large, well-shaped, with long lashes, and of gray color, which become dark when she is excited. Ordinarily thoughtful and somewhat sad, these eyes shine forth brilliantly when she is enthusiastic, which not infrequently happens, or sparkle when she jests, which happens very often. The slightest change of mind is reflected in the expressive eyes. The rest of her face is very commonplace. Her nose somewhat long, thin lips, large head, adorned with almost black hair.

She is very negligent with regard to her appearance. She gives no thought to it whatever. She has not the slightest trace of the desire, which almost every woman has, of displaying her beauty. She is too abstracted, too deeply immersed in her thoughts, to give heed continuously to things which interest her so little.

There is one thing, however, which corresponds even less than her exterior with the idea of an ethereal young girl; it is her voice. At first she speaks like most people. But this preliminary stage continues a very short time. No sooner do her words become animated, than she raises her voice, and speaks as loud as though she were addressing some one half-deaf, or at least a hundred yards distant. Notwithstanding every effort, she cannot break herself of this habit. She is so abstracted that she immediately forgets the banter of her friends, and her own determination to speak like the rest of the world in order to avoid observation. In the street, directly some interesting subject is touched upon, she immediately begins to exclaim, accompanying her words with her favorite and invariable gesture, cleaving the air energetically with her right hand, as though with a sword.

Under this aspect, so simple, rough, and unpoetical, she conceals, however, a mind full of the highest poetry, profound and powerful, full of indignation and love.

She is incapable of the spontaneous friendship of young and inexperienced minds. She proceeds cautiously, never advancing to supply with imagination the deficiencies of positive observation. She has but few friends, almost all belonging to her former connections; but in them is her world, separated from everyone else by a barrier almost insurmountable.

She lives much within herself. She is very subject to the special malady of the Russians, that of probing her own mind, sounding its depths, pitilessly dissecting it, searching for defects, often imaginary, and always exaggerated.

Hence those gloomy moods which from time to time assail her, like King Saul, and subjugate her for days and days, nothing being able to drive them away. At these times she becomes abstracted, shuns all society, and for hours together paces her room, completely buried in thought, or flies from the house to seek relief where alone she can find it, in Nature, eternal, impassible, and imposing, which she loves and interprets with the profound feeling of a truly poetical mind. All night long, often until sunrise, she wanders alone among the wild mountains of Switzerland, or rambles on the banks of its immense lakes.

She has that sublime craving, the source of great deeds, which in her is the result of an extreme idealism, the basis of her character. Her devotion to the cause of Socialism, which she espoused while a mere girl, assumed the shape in her mind of fixed ideas upon her own duties, so elevated that no human force could satisfy them. Everything seems small to her. One of her friends, X, the painter of whom I spoke just now who had known Zasulich for ten years, and was a very intelligent and clever woman, seeing her only a few weeks after her acquittal, a prey to these gloomy humors, used to say:

“Vera would like to shoot Trepovs every day, or at least once a week. And, as this cannot be done, she frets.”

Thereupon X tried to prove to Zasulich that we cannot sacrifice ourselves every Sunday as our Lord is sacrificed; that we must be contented, and do as others do.

Vera did so, but she was not cured. Her feelings had nothing in common with those of the ambitious who want to soar above others. Not only before, but even after her name had become so celebrated, that is, during her last journey in Russia, she undertook the most humble and most ordinary posts; that of compositor in a printing office, of landlady, of housemaid, etc.

She filled all these with unexceptionable care and diligence; but this did not bring peace to her heart.

I remember that one day, relating to me how she felt when she received from the President of the Court the announcement of her acquittal, she said that it was not joy she experienced, but extreme astonishment, immediately followed by a feeling of sadness.

“I could not explain this feeling then,” she added, “but I have understood it since. Had I been convicted, I should have been prevented by main force from doing anything, and should have been tranquil, and the thought of having done all I was able to do for the cause would have been a consolation to me.” This little remark, which has remained as though engraven upon my memory, illustrates her character better than pages of comments.

A unique modesty is only another form of this extreme idealism. It may be called the sign of a lofty mind to which heroism is natural and logical, and appears, therefore, in a form divinely simple.

In the midst of universal enthusiasm and true adoration. Vera Zassulich preserved all the simplicity of manner, all the purity of mind, which distinguished her before her name became surrounded by the aureole of an immortal glory. That glory, which would have turned the head of the strongest stoic, left her so phlegmatic and indifferent, that the fact would be absolutely incredible, were it not attested by all who have approached her, if only for a moment.

This fact, unique perhaps in the history of the human heart, of itself suffices to show the depth of her character, which is entirely self-sustained, and neither needs nor is able to derive any inspiration or impulse from external sources.

Having accomplished her great deed from profound moral conviction, without the least shadow of ambition, Zasulich held completely aloof from every manifestation of the sentiments which that deed aroused in others. This is why she has always obstinately avoided showing herself in public.

This reserve is no mere girlish restraint. It is a noble moral modesty, which forbids her to receive the homage of admiration for what, in the supreme elevation of her ideal conceptions, she refuses to consider as an act of heroism. Thus this same Vera, who is so fond of society, who is fond of talking, who never fails to enter into the most ardent discussion with anyone who appears to her to be in the wrong; this Vera no sooner enters any assembly whatever, where she knows she is being regarded as Vera Zasulich, than she immediately undergoes a change. She becomes timid and bashful as a girl who had just left school. Even her voice, instead of deafening the ear, undergoes a marvelous transformation; it becomes sweet, delicate, and gentle, in fact an “angelic” voice, as her friends jestingly say.

But that voice of hers is rarely heard, for in public gatherings Vera ordinarily remains as silent as the grave. She must have a question much at heart, to rise and say a few words about it.

To appreciate her originality of mind and her charming conversation, she must be seen at home, among friends. There alone does she give full scope to her vivacious and playful spirit. Her conversation is original, exuberant, diversified, combining racy humor with a certain youthful candor. Some of her remarks are true gems, not like those seen in the windows of the jewelers, but like those which prolific Nature spontaneously scatters in her lap.

The characteristic feature of her mind is originality. Endowed with a force of reasoning of the highest order, Zasulich has cultivated it by earnest and diversified studies during the long years of her exile in various towns in Russia. She has the faculty, which is so rare, of always thinking for herself, both in great things and in small. She is incapable by nature of following the beaten tracks, simply because they are the tracks of many. She verifies, she criticises everything, accepting nothing without a serious and minute examination. She thus gives her own impression even to the tritest things, which ordinarily are admitted and repeated by everybody without a thought, and this imparts to her arguments and to her ideas a charming freshness and vivacity.

This originality and independence of thought, united with her general moral character, produce another peculiarity, perhaps the most estimable of this very fine type. I speak of that almost infallible moral instinct which is peculiar to her, of that faculty of discernment in the most perplexing and subtle questions, of good and evil, of the permitted and the forbidden, which she possesses, without being able, sometimes, to give a positive reason for her opinion. This instinct she admirably evinced in her conduct before the court on the day of her memorable trial, to which, in great part, its unexpected result is to be attributed, and in many internal questions.

Her advice and opinions, even when she does not state her reasons, are always worthy of the highest consideration, because they are very rarely wrong.

Thus Zasulich has everything to make her what might be called the conscience of a circle, of an organization, of a party; but great as is her moral influence, Zasulich cannot be considered as a model of political influence. She is too much concentrated in herself to influence others. She does not give advice, unless she is expressly asked to give it. She does not, on her own initiative, interfere with the affairs of others, in order to have them arranged in her own manner, as an organizer or an agitator endeavors to do. She does her duty as her conscience prescribes, without endeavoring to lead others by her example.

Her very idealism, so noble and so prolific, which makes her always eager for great deeds, renders her incapable of devoting herself with all her heart to the mean and petty details of daily labor.

She is a woman for great decisions and for great occasions.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf