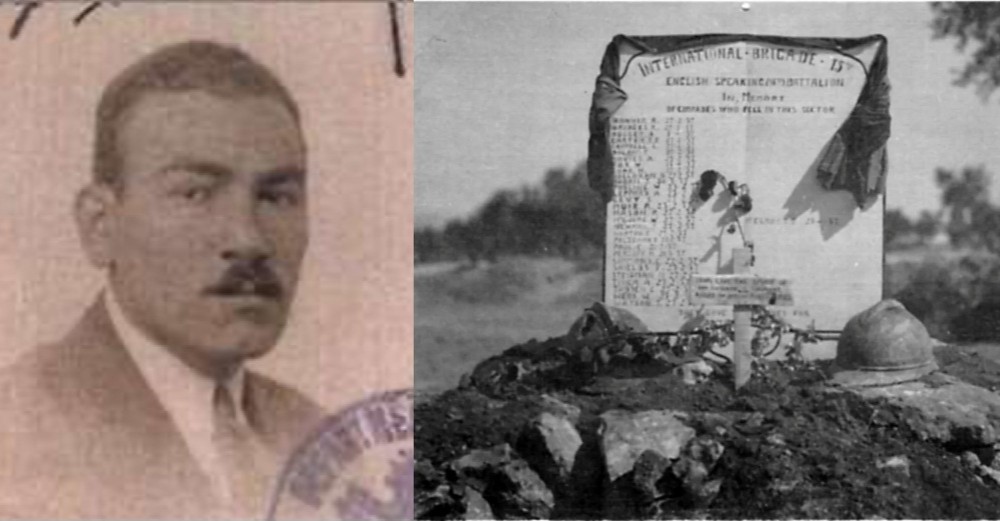

One of the first to die on a disastrous day for the Lincoln Battalion, 27-year-old New York teacher Joseph Streisand was shot while attempting to place a signal on February 27, 1937 during the Battle of Jarama. Dozens of members of the Battalion, mostly from the U.S. and Canada, would be killed in the suicidal assault on fascist trenches that immediately followed.

‘Teachers Union Member Dies a Hero in ‘No Man’s Land’ in Spain’ from The Daily Worker. Vol. 14 No. 117. May 17, 1937.

A complete account of how Joseph Streisand, a leading member of the WPA Teachers Union, Local 453, was killed in action on February 27 while carrying out a highly dangerous assignment during an attack against the fascist position on the Jarama River Front, has been received by the Teachers Union in a cablegram from one of Streisand’s comrades in the Lincoln Battalion.

A campaign has been launched in the union to raise a “Streisand Memorial Fund” for the purchase of an ambulance for Spain.

The cable follows:

Joseph Streisand was a trusted personal runner, an extremely dangerous job, for Robert Merri- man, Commander of the Lincoln Battalion. During the first American attack on the Jarama River front, February 23rd, where the enemy was attempting to cut the Valencia-Madrid road, Streisand five times journeyed across no-man’s land, raked by the fiercest machine-gun fire, bearing most important battalion orders to company commanders.

When night fell, and firing ceased, he was unscratched. Commander Merriman described Streisand as follows: “Very quiet, very responsible and always interested in spending his spare time in improving conditions in the trenches. by helping to improve the dugouts, cleaning up, building better parapets, etc.”

KEEPS CONTACT

The 27th of February dawned wet and cloudy. At 11 A.M. the Americans launched an offensive up the slope of an olive field, aiming to capture the enemy positions which dominated the strategic government-held road. Streisand was in the battalion headquarters of the front line trenches.

During the early part of the attack he kept contact between the Lincoln Battalion and other sections of the International Brigade. This required long, dangerous trips over rocky, exposed terrain and he was open to the grimmest fire.

One hour after the launching of the attack, Merriman was informed over the field telephone that government planes were coming to assist in the attack. It was necessary, therefore, to place white airplane signals in the most advanced positions so that the government planes would know where these positions were. “We were moving up all the time,” Merriman explained, “while our own planes were raking the enemy lines with machine-gun fire.”

In order to protect our own men, Merriman called Streisand and asked him to put out the airplane signals. “Although this was the first job of this kind that he had ever done, Joe did not ask for further instructions.

SETS OUT

“He began gathering bandages and old shirts–anything white he could find suitable for signaling. With the material tucked inside his shirt, and accompanied by a slightly wounded runner, Streisand went along the trenches to the extreme right of the American position.

“The lives of many of our men depended on the proper placing of these signals. He crawled over the parapet into no-man’s land where the deadliest fire was raking the earth. He reached the proper position safely and set the signal, only to be mowed down by a burst of machine-gun fire. Dragged back by stretcher bearers, he died-shot through the head.

“I saw him carried by battalion headquarters through the trenches, en route to the first aid station,” Merriman continued. “We all gave him the anti-fascist, clenched-fist salute. He died a few minutes after.”

There is a cemetery at that Jarama olive field, and Joe lies buried there, his grave marked by stones where his name is firmly fastened. “Streisand’s death was felt most sharply by the soldiers themselves, who knew him for fearlessness and coolness under fire,” Merriman testified, “that is a real attribute here, let me tell you. How we long for people who can hold their heads.”

Signed by another member of the union at the front.

Streisand Among Leaders Of WPA Teachers’ Union

Joseph Streisand was born in New Jersey 27 years ago. He received his education in the New York City schools. The depression forced him, as it did 20 million other Americans, on the relief rolls. As research worker on Project 6063, at the Speyer School, he became active in the WPA Teachers Union Local 453, and at one time was chairman of the Speyer School local. His duties here brought him into constant contact with the injustices that beset WPA workers. Success in adjusting local grievances led to his appointment to the Central Grievance Committee of the union of which he later became co-chairman.

Intensely anti-fascist, he decided that his place was in Spain, fighting side by side with the Spanish people in defense of their liberties. The WPA, however, put a temporary halt to his plans. On December 4th, he and 110 others were unjustly dismissed in a general lay-off of non-relief personnel and all those “not in current need.”

Although he was impatient to leave, he considered it his duty to postpone departure until he and the 110 others were reinstated. On December 10, Joe led 60 of these dismissed workers in an all-night sit-in at the headquarters of the ERB, to force the relief authorities to expedite the proper certification of these workers as former relief clients. As a result of this action, he and the others were reinstated. Immediately following his reinstatement, he left for Spain.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: