Built in to circumvent an unnavigable stretch of the Columbia River and facilitate the extraction of Pacific Coast resources, the Celilo Canal cost huge amounts of money and many lives. The entire area was flooded in 1957 to make way for Dalles hydro-electric dam. ‘Wilby Heard’ gives us a fantastic on-the-ground, workers-eye-view of the process of construction.

‘“Our” Cililo Canal’ by Wilby Heard from International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 8. February, 1914.

CAPITALISM believes that certain achievements, like certain little children, should be seen and not heard, while others again must not even be seen until a certain age. They must not make their debut till the profits to flow from them are all corralled and headed safely for certain favorite coffers. Such an achievement is the Dalles-Cililo Canal, now under construction on the mighty Columbia River on the Oregon side, some ninety miles east of Portland.

Approach any politician or business man and mention the Cililo canal, and if he does know anything about it, he glares at you, fires a thousand and one questions at you, to your one, demands your pedigree, and whether you give it or no, he informs you that there is nothing to tell about it, and that no publicity is asked for on the matter, anyway.

In the last year or so a few skimpy statements on this governmental chunk of philanthropy have found the light. And the present seems to promise that the near future will tear down the blinds altogether, which means that someone’s pockets are well lined and the graft well cinched.

The reason given by a few for this silence is that the Oregon-Washington Railroad & Navigation Company had its heart set against the canal, and the matter was pulled off on the Q.T. to get one over on it. But this holds no water, since the congressman who got through the first appropriation is said to be a particular friend of the poor O.-W.R. & N.

Far more plausible are the few rumblings escaped from the dungeon where the truth lies chained till the fat checks are cashed. Chief among these is the story that things must now stay hushed till the U.S. government and the states of Oregon and Washington make their appropriations of $15,000 each for the construction of a proposed dam across the Columbia River right at the Cililo falls, where the canal opens. This dam, it is claimed, will have a waterpower generating more force than the Niagara Falls.

But it is declared that if the dam be built it will make utterly useless the canal by flooding over half the canal territory. And, almost strange to say, that part of the canal to be affected most by the dam is the part about complete So mum must be the word till that dam money is safely landed and the canal completed. Then some gilded-tongued congressman will up in his glory for a new appropriation for a new canal to take the place of the present canal which is being built to make it useless.

Another reason for the silence is given by men who know the river, and these claim that even should the dam not materialize, the canal must still remain a white elephant because of the river between The Dalles and Cililo being so narrow and so rapid at places as to make boat navigation next to impossible. This, too, seems to explain why the O.-W.R. & N. pretends to be ignorant of the whole scheme which is being pulled off so close to its line as to remove its tracks along that section so as to give the diggers more room.

Should the undertaking, however, have been for the good of the people, instead of a few business philanthropists and contractors, the canal could prove a valuable asset in more ways than one. And since ere many decades rush by the workers will own the machinery of production and transportation, a few words on the canal may be in place.

The Dalles-Cililo canal will be about eight and one-half miles long; have five locks, with a total lift of seventy feet. The idea was born in the balmy days of Henry Villard, the great western railroad promoter, and brought to a paying proposition for contractors by The Dalles, Portland & Astoria Navigation Company.

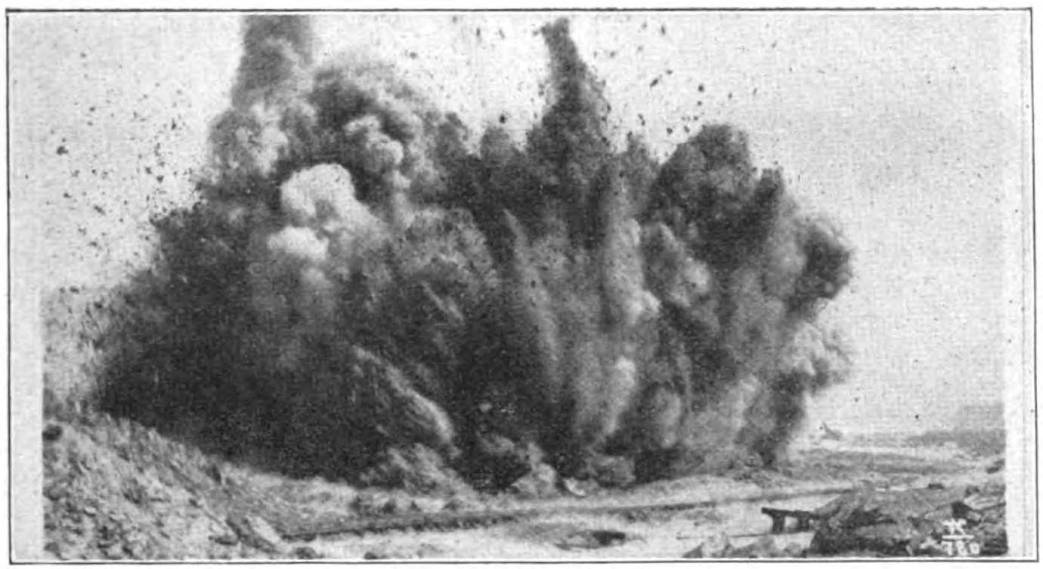

AND LOOSENED 600 YARDS OF ROCK AND EARTH

If the rapids and narrows below the lower end of the canal be overcome and the upper end be not dammed, the canal will open the river to boats as far as Lewiston, Idaho, on the Snake River, and to Kettle Falls, Wash., on the Columbia. And should the obstruction of Kettle Falls be removed, rumors to that effect already being afloat, it will open river traffic for five hundred miles into British Columbia. Thus it will make all of the Kootinia lake country, which is rich in coal, copper, silver and some lead and gold, tributary to ocean commerce.

This canal project was approved by Congress in 1905. And before the “builders” are through with Uncle Sam it will cost him about $5,000,000. The work for the common dubs involves the excavation of 700,000 cubic yards of earth, 750,000 cubic yards of sand, and 1,300,000 cubic yards of rock. They will construct 2,000,000 cubic yards of concrete, and about 5,000 cubic yards of rubble masonry. The human ants practically began to get their grub for this task in 1910.

It is claimed that this little job will come to an end in 1916, and then the flowing waters will carry the Inland Empire’s products, main among which are wheat, hay, fruit and livestock, to Portland via river and to the world market via ocean courses. That does not mean, however, that prices of these commodities will be lowered to the working class thereby.

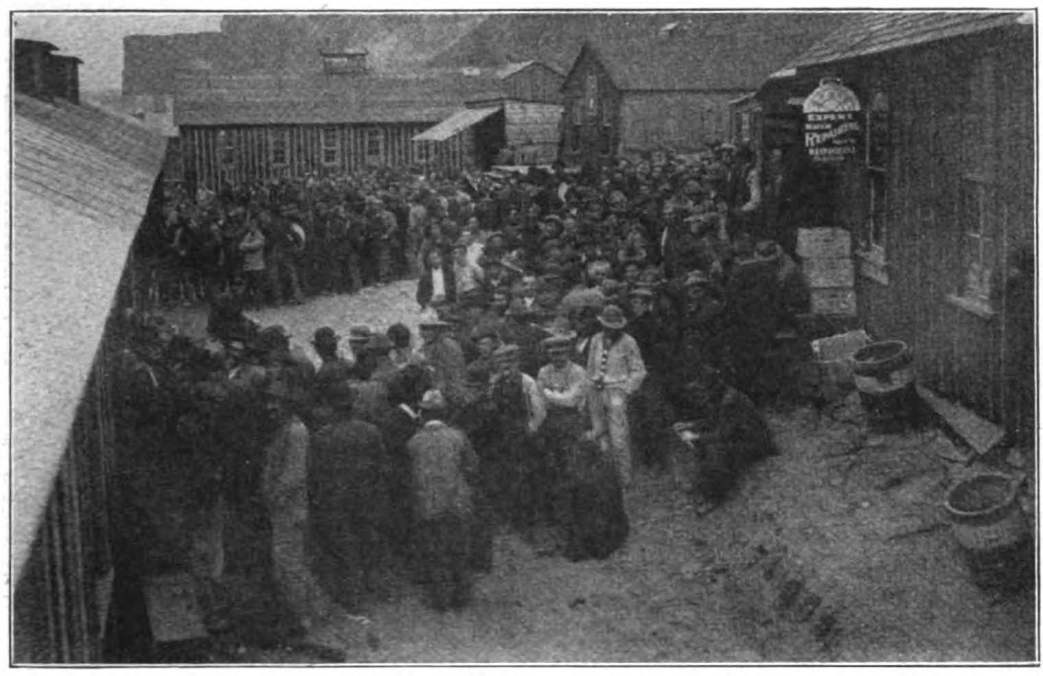

Now, as to the labor conditions maintaining at these government camps, the usual capitalist methods prevail. The 1,200 to 1,400 men are separated into three camps—Big Eddy, or Camp 1; Camp 2, an annex to Big Eddy, and Robert, or Camp 3.

Stationed at Big Eddy are the highest officials and their underlings, the clerks and straw Dosses, and a gang of about 200 common delvers. This is the camp to which visitors are taken. The few articles which have crept into the press of late have all been centered about Big Eddy, with the impression between the lines that the same holds true of all the camps. And true it is that Camp 1 is the best managed of the lot. From what can be gathered, the aim of the officials here seems to be to treat the wage-slaves as fair as can be expected under this hellish system.

For one reason or another, men leave every day, and every sun looks down upon a greater number of blanket stiffs coming in than can be put to work. The majority of newcomers, as well as many of those already at work, for some time are toilers well starved, and their table manners lead the “well bred” to conclude that these bunk dwellers had their etiquette caught in the railroad ties they measured, and that they left them to perish there. So much for Camp 1; but Camp 3, all declare, is a hell hole of disgust and abuse.

Camp 2, as stated before, is but a “Jungle Town” suburb to Big Eddy. In this “suburb” 200 men or more, some with families, waste their nights as well as days. These consist in the main of foreigners who feed themselves. These two camps are about three miles apart, and midway between them is a small schoolhouse for the children of these workers.

Robert, at present, holds the biggest herd of laborers. And here is where complaints are loudest. While 800 men are employed, the bunkhouses can accommodate but 500. The ventilation is very poor. The bunks are arranged in two layers, one above the other. The men furnish their own bedding, and all mattresses consist of Oregon pine or fir, soft enough for any rock to linger on.

The men here, as at the other two camps, work in two shifts of eight hours each. The night gang gets through at 2 a.m. and their bunkhouse, being far too small, the overflow crowds into the bunkhouse of the day shift for warmth and are the means of aiding the board mattresses in driving all sleep beyond the towering palisades of Camp 3.

The dining rooms at both camps are walled off into three separate divisions: One room for the high and holy officials, one for the straw bosses and clerks, and one for just the common herd. A few say that the food served is the same for all, many declare that it is served according to caste. Among the latter is a waiter who served

the foremen’s mess. This waiter told me that while the officials and straw bosses get real butter, the actual workers never see anything but oleomargarine.

He also stated that he personally saw some potato bills which had come in from Portland, and that there were two different bills. The one for the government was marked $1.25 per sack, and the one for the man who had to do the paying was marked 25 cents per sack.

Another of his statements worthy of publication was that a certain bookkeeper was transferred to the Philippines for tattling the fact that during the winter of 1910 the pay roll at Washington numbered 300 men, while at the camps the number of men actually at work was twenty-five. So if someone doesn’t become a fat philanthropist and good church member by the time the canal is finished, it won’t be the pay roll’s fault.

Sanitation, too, could be improved a thousandfold. One instance will suffice. There are twenty toilets, all in one room, for the accommodation of 800 men. The crank to the flush pipe is off to one corner of the place, and instead of running all the time, the water is supposed to be turned on and off by each individual—a thing the laborers all ought to bear in mind, but which many do not.

There is but one small hospital, and that at Big Eddy, and this is ever brim full. A man hurt at Robert has to be hauled fully five miles or more on the rickety Portage railway, which, by the way, is state owned, to the hospital for treatment. It seems true, however, that commercial murderings are not as numerous here as they are in privately run institutions.

The latest death occurred at Camp 3, on Tuesday, December 2, last. The victim was one Frank Lynch, who was working on the bed of the canal. A skipload of dirt, weighing a ton and a half, dropped twenty feet, crushing him beyond recognition. The accident was due to the breaking of a gooseneck on a derrick.

The verdict of the coroner’s inquest was that the death was due to the negligence and carelessness of the engineers. But the gentlemen demanded a second inquest, claiming that because the witnesses at the first inquest were all laborers they were prejudiced. They were promised another investigation, but at the time of this writing nothing new has come forth.

But it is an ill wind that blows no one good. This government job is, at present, like an oasis in the desert to many of the vast army of out-of-works. On their travels from place to place in search of a grubsupplier, hundreds pause here for a few weeks’ recuperation, to earn enough to take them to some other place where lying ads glare brightly from the pandering columns of the capitalist papers.

Rebels! The camps are overrun with them. And the gospel of the toilers is being drilled into the minds of the sleeping slaves as carefully and accurately as the dynamite holes into the canal rocks. The I.W.W. has a fair and solid representation among that gang. And it is but right to mention that the good work is going on in a healthy manner, though much of it must be done under cover. Our day is dawning and we have no reason for despair.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n08-feb-1914-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf