A Russian stays a night in New York City’s Bryant Park among the detritus of imperialism, homeless veterans of the World War sleeping rough in the world’s richest city.

‘In The Lower Depths: A Night with the Unemployed in Bryant Park’ by V. Klimov from The Toiler. No. 193. October 22, 1921.

A few days before the November revolution in Russia I happened to see Gorky’s famous drama, “In the Lower Depths,” as played in the Moscow Art Theatre. The impression of Stanislavsky’s admirable presentation was overpowering. I perceived the grim reality of those living symbols of the decaying world which we usually pass without notice. “There is the last phase,” exclaimed my companion after the performance, “Our present system can sink no lower. When men with energy and enthusiasm, men who have offered society their blood and their muscle, their ability and their devotion, are condemned to perish miserably, what remains for the future? The great change is bound to come. The old world must be wiped out. The day is at hand when all these at the bottom, all the wretched outcasts, will rise to avenge themselves upon society and make an end of this terrible social system.” This remark impressed itself upon my memory and recurs whenever I see those at the bottom, those who have been forced by capitalist society into the lower depths.

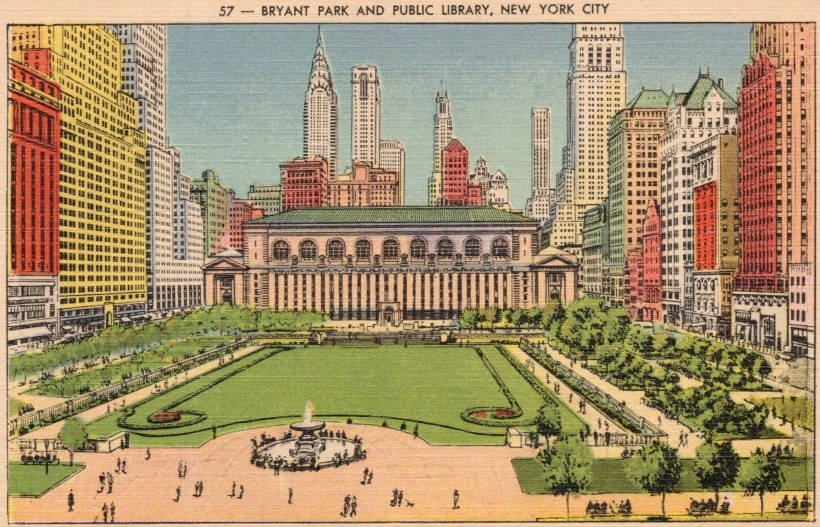

A few days ago I went to Bryant Park with some American comrades. It was rather late in the evening. Fifth Avenue was swarming with automobiles filled with self-satisfied men and women in evening dress. The side-walks were crowded with richly-clad pedestrians just emerging from various places of amusement. One of my comrades said, “Here is wealthy New York enjoying life to the full without ever realizing or giving a thought to the fact that not one block away there is the misery of people in rags, without a roof over their heads, starving.”

Almost at once we were in Bryant Park, and I encountered a scene such as I had never imagined could exist in the heart of New York. Scattered about on the turf worn thin by human feet, were heaps of muddy white. They might have been piles of dirty snow about to melt, yet these were human bodies covered with old newspapers. Some were sunk in heavy slumber, some were lying with wide-open eyes looking into the clear sky overhead. One of those awake noticed me and remarked bitterly: “Newspaper reporters, eh! Want to make a job, coin an extra couple of dollars out of us?” Other eyes followed us with a blank, weary expression as we moved on.

Not far away a group of men were sitting under a lamp- post playing cards for buttons. They were so absorbed in the game that they did not even notice us. Some one called out “Joe, don’t forget us,” and the man named Joe came up grinning, and explained “When you’ve got no coin and you want your rebellious stomach to shut up you have to gamble on the buttons from your own rags. I offered Joe a cigarette. It was evidently an event for him as he clutched eagerly at it. As he inhaled he remarked, “I hadn’t smoked for five days now, and I need fifty a day. Can’t do with no less. It’s become a habit, y’ know.”

Joe was clad in nondescript rags, which might originally have been men’s or women’s, clinging to his body in shreds. The shoes exposed his naked toes black with mud. His bare breast was in no better shape. He wore no shirt, no socks. Owing to his unkempt hair and his rough face, which had not been touched by a razor for weeks, it was impossible to tell whether he was young or old. In the dim light one could only see his eyes glowing as if in fever. We offered him some sandwiches which he proceeded to stow away with such beastly greed that I turned away. It was painful to look upon the voracity to which this man had been driven by hunger. He seemed to have forgotten all about his surroundings. Only his loud munching was to be heard, and we felt ashamed, ashamed for our own satiated selves- ashamed for humanity.

A little later, seated on the bench beside him, we learned that Joe was an ex-service man. His home was in the far West, where he left an old mother and sister. They both depended upon him for their support. He had worked in a shoe factory, but it is six months now since he lost his job. He sold all of his scanty possessions, left nothing for himself and sent the money to his mother. Now he is absolutely penniless. Six weeks ago he was thrown out from the cellar, where he was living with several others, because they could not pay the five dollars rent. He doesn’t care much about himself, but he thinks of the old mother and little sister. What will they do? The tears came into his eyes when he talked about them. He had turned to the American Legion but in vain. “You can bet,” he said bitterly, “that before I die of hunger like a dog somewhere under a fence, I shall get even with those fakers at the Legion. And I am not the only one who has got that notion. Look at the boys here; they all say they’re going to do the same as the Bolsheviks did in Russia. They’re the real guys, them Bolsheviks. When we get down to business, we will send Rockefeller to sleep in this park and we’ll take rooms in his house. Wait till winter comes. We’ve got nothing to lose, anyhow. Ha, ha, ha! Ain’t I right?” “See here,” and Joe resumed his speech after some moments of silence, “there is a feller over there among the papers, that skinny one with the long hair and the lady’s jacket. He’s an Italian. He’s been with Mr. Ledoux in Boston, at the slave auction. Well, nobody cared to buy him, there’s no flesh on his bones. Bones, that’s all there is to him. He won’t hold out very long now. He has not been able to earn a penny for eight months. He used to be a tailor. Well, he’s always talking about the Bolsheviks. He says we would be better off if Honorable Lenin was here. Never mind, boys, we’ll show them what we can do first, then we’ll get Honorable Lenin to come here and fix things up. Say, Willie, come over here. Quit your game.” Willie rose from his place and came toward us with the others. There were ten of them. All of them were ex-service men and Americans. Willie was the only immigrant, but he talked a fluent English. They all looked alike, haggard, unkempt, with feverish eyes. They eyed us suspiciously but Joe reassured them. Never mind, they’re all right, no sleuths.” I asked, “How do you know that?” Joe replied without hesitating, “Never mind, I can tell a spy a mile away. These skunks can’t fool me. Why I’ll bet you’re Bolsheviks yourselves.”

The slender Italian gave us a look as if to say: “That’s all right, we understand each other.” However, Joe seemed to be in a good mood and wanted to do all the talking himself. “Well, boys,” he said. “Some concert in your bellies! It’s fiddling there just as in Caruso’s throat, as Willie would say, eh?” They all smiled, wanly, as sick children might.

We gave them what money we had and Willie went to get some sandwiches and cigarettes. Now they all started to talk. And when I listened to their talk and looked at them, I thought I was seeing Gorky’s “In the Lower Depths,” played this time in English in the open air. Here they are, these living symbols of the decayed old world. What is it that keeps them alive, what are they waiting for, what are they hoping for? I hear the answer in Willie’s sick voice coming from the depths of his bare, thin chest.

“Steal! Why, everything belongs to us. These skyscrapers, this library, it’s all our sweat that made it. And made it. And we! We’ve got to lay here in the parks, and it’s a favor that they don’t turn us out. But we’ll pay them for all their favors. We’ll give them a lesson. Never mind!”.

The others nodded their heads. Joe returned with the cigarettes and sandwiches. They threw themselves upon the food like a pack of hungry wolves. We stepped aside and listened to the noise of their munching jaws. A policeman appeared and examined us mistrustfully, then walked away as if satisfied that there was no “revolution” in sight.

We left the park at daybreak. In the first rays of dawn, the skyscrapers had the air of ghosts waiting for the unveiling of a mystery.

The New York of the Rich is sound asleep. All is still. But it is a sullen stillness. For Bryant Park never sleeps. Bryant Park is never quiet. A storm of hate and bitterness is gathering there among the homeless and starving denizens of the parks which will break one day and sweep all before it. They curse their fate and the society which has brought it upon them. Like the cripples and hunchbacks of Sholom Asch’s tale they go, “without flags, with no songs. Only a curse is folded in their rags, is heard in their weary steps, the most terrible curse to our civilization, a curse which makes the old world shrink in a paroxysm of terror, in an agony of death.”

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n193-oct-22-1921-Toil-nyplmf.pdf