By far, the best showing of the Socialist Party in a New York City mayoral race was Morris Hilquitt’s 1917 run, gaining over 21% of the vote and nearly coming in second. The Socialist Party had split that April over the war, with the pro-war Right asserting that the Party would isolate itself with its militant anti-war position. To the contrary, the Party gained massively, in both new members and votes, after it turned to the Left as the war approached. Below is an illuminating analysis and context of the race from leading Left Winger, New York Volks-Zeitung’s editor, Ludwig Lore.

‘The New York Mayoralty Campaign’ by Ludwig Lore from Class Struggle. Vol. 1 No. 4. November-December, 1917.

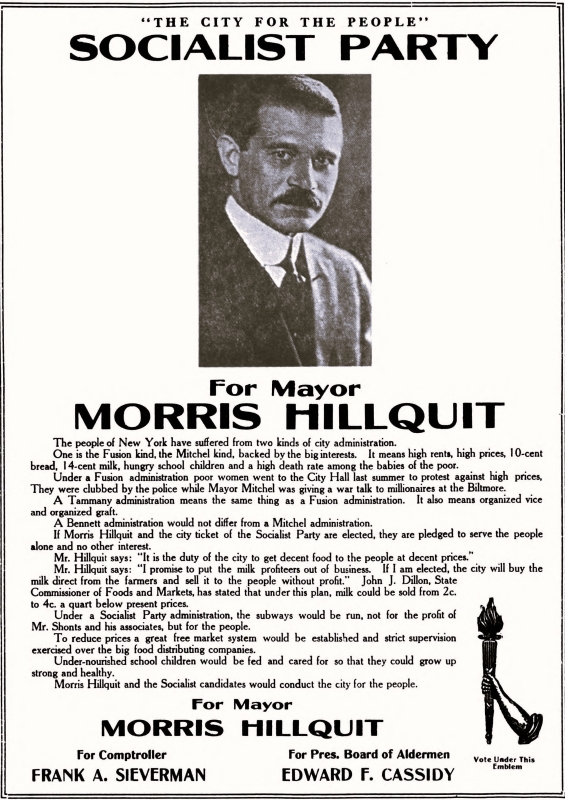

Apparently the New York Municipal campaign of the Socialist Party was a great success. An increase in votes from 33,000 cast for Charles Edward Russell in 1913 to 142,000 polled for Morris Hillquit in 1917, the election of ten Assemblymen, seven Aldermen and one Municipal Court Judge, have established the prestige of the Socialist Party as a political factor in Greater New York. Not only newspapers like the N.Y. Evening Post and The World, but political organizations like Tammany Hall, with its unparalleled capacity for judging the real significance of election returns, admit that the Socialist Party has become a dangerous competitor.

To the Socialist, this is, however, only one of the criterions by which a campaign may be judged—and by no means the most important one. Does the gain in prestige, before the general public coincide with a real augmentation of our Socialist strength? Was this campaign worthwhile, from the point of view of a Socialist? Has it served to bring us a step nearer to the final aim of our movement? Has it made Socialists? Has it done more than to persuade a few thousand people to vote for candidates on a Socialist ticket?

We nominate candidates not for the purpose of electing a few men or women to office—but mainly for the purpose of taking away political power from the capitalist class and placing it into the hands of the working class. And this, again, is done with the understanding that it is not enough to elect workingmen, but people who understand the incessant struggle between capital and labor, and who recognize that the struggle can be ended only by the socialization of the means of production.

If there are to-day, in the city of New York, more working people than there were three months ago who understand the essence of Socialism, then the 1917 municipal campaign of the Socialist Party was a success, was well worth all the sacrifices in time, effort and money that it demanded.

Is the increase in socialist sentiment and understanding in sound proportion to the actual vote cast for our candidates? This, and this alone, is the criterion by which the true worth of this campaign may be judged.

* * *

There is no question that the main issue this year was not Socialism, but Peace. The peace issue overshadowed all other questions. The people at large were indifferent to everything else; the one question of war and peace was everlastingly in their minds. If there had ever been any doubts in our minds as to where the American people, or at least the population of New York, stood on the war, a visit to a few of the innumerable hall and street meetings would have effectually banished them.

At all the many meetings we attended, on the Jewish East Side of Manhattan, or in the heart of the American West Side, among the Italians of Harlem, or in the real cosmopolitan Scandinavian, Irish-English districts along the South Brooklyn water front, even the poorest speaker could not fail to arouse the greatest enthusiasm when he touched upon the demand of immediate peace. On the other hand we could not help noticing how coldly those comrades were received who spoke only of municipal affairs and state problems, and forgot to mention the war situation. We distinctly recollect two such cases, where the speakers were not only of the highest type, but possessed the rare gift of entertaining their audiences while educating them in the fundamentals of Socialism as well.

It was, under these circumstances, inevitable, that the campaign should become one of protest and demonstration rather than one of education. It could not have been otherwise, much as most of us would have liked to have it so. Since it so happened that the Socialist Party was the only political organization that stood in opposition to the war and was not afraid to say so, many who, a year ago, were so prejudiced against Socialism that they refused to listen to a Socialist speaker or attend a Socialist meeting now came to us, read our literature, donated to our campaign-fund, and in many cases were eager to assist in every way they could. For the first time in the history of the Socialist movement of New York our meetings were crowded with audiences made up of such newcomers. To speak to these people in the phraseology of scientific Socialism would have been more than futile.

One might, perhaps, find fault with the exaggeration of the importance of municipal reform. This is, however, a fault common to all municipal campaigns.

* * *

The one real mistake made in this campaign was the exploitation of a common garden-variety politician like Mr. Dudley Field Malone. If this campaign was a fight for Socialism, this man, an avowed adherent of the present system, surely had no place in it. Neither should he have been allowed to speak from the same platform with Morris Hillquit, Sieverman and Cassidy in a campaign fought with the slogan “Down with the war!” For he declared frankly and unhesitatingly, at every meeting at which he spoke, that he was in full agreement with the National Administration as far as the war was concerned, that there was only one point of disagreement between them: the federal woman suffrage amendment. He supported—from the platform—conscription, favored a thorough war-policy, and indorsed, with special emphasis, the Wilsonian peace idea. He went out of his way to contrast President Wilson favorably with war shouters of the Root-Roosevelt type, contending that they stood for conquest and imperialism, while Mr. Wilson symbolized the highest ideals of Democracy and Progressivism.

To the “business” mind, there was, of course, a third “issue” in the mayoralty fight. The “good” people of New York had united to defeat the bad boy of New York politics. All respectable men and women had joined hands in the Fusion camp once more, to kill that much hunted beast that has the unfortunate habit of always surviving his most expert hunters. Mr. John Purroy Mitchel, this noble representative of the finest of goodygoody politics, controlled and operated exclusively by the big capitalistic interests, was chosen for the second time, to be the savior of society, from the evils of Murphyism. But Mr. Malone, who, like the Mayor himself, is a graduate and a former ardent and obedient member of Tammany Hall, believed the choice of the reform element to be an unfortunate one, and was sure that Mitchel had no chance of election and supported our candidate, therefore, not from choice, but as the lesser of two evils. Surely, this is the impression that his constant reiteration of the cry: “to beat Tammany you must vote for Hillquit,” was bound to create. But even herein he was not quite above board; for he repeatedly emphasized in public statements for the press and at meetings, that he would gladly have supported Tammany Hall had it been led by an upright man like Mr. Smith, the Democratic candidate for President of Board of Alderman, instead of a man like Murphy. Tammany led by a man with the “outward appearance of decency” of Gaynor fame, would to him have lost all of its terrors.

It is already rumored—and Mr. David Lawrence, the well-informed Washington correspondent of the N.Y. “Evening Post,” indicated this in the columns of his paper—that Mr. Dudley Field Malone will be a gubernatorial candidate in the coming state election on one of the capitalistic “reform” tickets. This “rumor” receives support from the fact that the new mongrel political organization, “The National Party,” has announced this oratorically gifted gentleman as one of the twenty members of its National Executive Committee.

It seems to us extremely poor politics from any point of view to have allowed Mr. Malone to present himself before tremendous audiences of the working class as its friend, and to assist him, in this way, in his hunt for bigger game.

* * *

A review of the municipal campaign would be incomplete without giving due attention to the activity of those of our ex-comrades, who under the guise of “Internationalism” took pains to attack and calumniate the Socialist Party, its membership and, with special venom, Comrade Hillquit. If ever there was a disgusting and sorry spectacle, it was the one we were forced to witness in New York, during the month of October 1917.

First came the little band of heroic knights yclept “Alliance for Labor and Democracy” under the leadership of that “mental giant” Chester M. Wright, and his boss, the unspeakable Maisel. Night after night their chariot toured the Jewish districts, and always with the same pitiful success. No one took them seriously enough to listen to their tirades, or even to jeer at them. The population of these districts—even its unsocialistic part—showed its contempt so plainly that these “real socialistic” supporters of the most outspoken representative of the big financial interests, the intimate friend of the Morgans and Vanderbilts, of the Roots and Roosevelts, became the laughing stock of the whole campaign.

Then the big guns appeared upon the scene to save the situation. Mr. Charles Edward Russell, who as the Socialist mayoralty candidate—four years ago—had contributed to Socialist literature a splendid characterization of the scare-crow Tammany-cry, was brought all the way from Michigan to speak for Mr. Mitchel. He spoke just once and—disappeared. The cordiality of the reception offered to him—the cries of “traitor” and “renegade” that greeted him, sent him back to Michigan, where he is “working for the government.” William English Walling, the industrious author of at least five newspaper articles daily—every one of them written for the capitalist press and for the benefit of anti-Socialist capitalist politicians, did his goodly share. Mr. Phelps Stokes, whose honesty and earnestness of purpose everybody appreciates as much as his lack of Socialist understanding, spoke at a number of meetings for the Fusion cause. But saddest of all is the case of Henry L. Slobodin, who has hopelessly sacrificed a splendid record of more than twenty years of useful service for the labor and Socialist movements, by working side by side with Root, Roosevelt and Hughes.

The most amusing—or shall we say tragic—of the extravagant pretenses made by these men, is their claim to represent in this country, the ideas, principles and tactics of Karl Liebknecht, the staunch and uncompromising foe of capitalism and militarism. They feign ignorance of the fact that this real internationalist and revolutionist has proclaimed it to be the duty of all Socialists to fight their own capitalist governments and give no quarter. By using Liebknecht’s name in this peculiar manner they not only do injustice to the Socialist movement of the United States but create an impression of Karl Liebknecht which cannot but lower him in the eyes of the world.

* * *

To what extent, then, did the municipal campaign prove a success from the Socialist point of view?

The Hillquit vote was somewhat above 140,000, the vote for the head of the state ticket, Comrade S. John Block, candidate for Attorney General, almost 120,000 in Greater New York. The vote cast for Comrade Block is generally conceded to be the straight Socialist vote. Four years ago our candidate for Mayor polled 33,000 votes. A year ago our candidate for governor received 38,500 votes in the city, while our presidential candidate polled about 10,000 votes more. This increase in the straight vote, therefore, is proportionally much larger than that of the floating vote.

This proves one gratifying fact—that the real pro-German vote went to Hylan and not to Hillquit. This vote, undesirable from any point of view, went to Hylan because the typical pro-German represents that element of society that belongs to the middle-class and is essentially bourgeois and therefore anti-Socialistic in its feelings and political affiliations. No branch of the American Socialist movement is so conspicuously lacking in professionals and “intellectuals” as the German Language Federation. Nowhere is the genuine labor element in such an overwhelming majority in the Socialist organization of this country as in the German speaking branches.

The genuine pro-German could have been persuaded, perhaps, to vote for an isolated candidate who “had a chance.” He would never, however, allow himself to be so far swayed by his idealism to vote for a lost cause. He will vote the straight Democratic or Republican ticket, as may seem, at the time, most compatible with his immediate interests. But nothing could persuade his pennywise mind “to throw his vote away.” We know of no more reactionary influence in the United States today than that of the average German voter.

* * *

The battle has been fought and won. A new and a bigger fight is on, the fight, not for “humanity and the people,” as it was rather unfortunately expressed in our city campaign, but for Socialism and the working class.

Education along the lines of revolutionary Socialism, organization of the newly won forces to prepare them for the final aims of the Socialist movement, the emancipation of the working class throughout the world, now more than ever before must be our goal.

The Class Struggle and The Socialist Publication Society produced some of the earliest US versions of the revolutionary texts of First World War and the upheavals that followed. A project of Louis Fraina’s, the Society also published The Class Struggle. The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America. ‘In the two years of its existence thus far, this magazine has presented the best interpretations of world events from the pens of American and Foreign Socialists. Among those who have contributed articles to its pages are: Nikolai Lenin, Leon Trotzky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Lunacharsky, Bukharin, Hoglund, Karl Island, Friedrich Adler, and many others. The pages of this magazine will continue to print only the best and most class-conscious socialist material, and should be read by all who wish to be in contact with the living thought of the most uncompromising section of the Socialist Party.’

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v1n4nov-dec1917.pdf