A two-parter looking at the impact of China’s revolutionary crisis on a rising class struggle and Communist movement in the Dutch colony.

‘The Revolutionary and Labor Movement in Java’ by P. Bergsma from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 5 Nos. 73 & 74. October 8 & 15, 1925.

The violent collisions between the tremendous masses of China and the imperialist Powers, are having also a great influence on the national revolutionary movement in Indonesia.

Up to the present the native population has always carried on its struggle against Dutch imperialism independently and not in connection with the 800,000 Chinese who reside there. After the world war a certain contact did, it is true, develop between Chinese and native workers; the difference in religion however led again to a separation and even to mutual hostility.

Now that the great national fight against European imperialism has flared up, the Chinese and natives of Indonesia work together in brotherly agreement in the support of this struggle. The Chinese trading companies in Java send large sums of money to maintain the fight. Of far greater import however is the fact that thousands of poor Chinese in common with the Indonesian workers, call upon the people to fight against imperialism, and organise big demonstrations. In many of these assemblies conflicts have arisen between the Chinese and Indonesians and the police.

Even the simplest Chinese people, those suffering most from oppression, the so-called “contract coolies”, collected amongst them 10,000 Gulden for the struggle in China. They thus put to shame the leaders of the Amsterdam International who have, up to the present, refused any financial support.

The Government of Java passed a law forbidding the collecting of money for the struggle in China on the grounds of its being raised in aid of a cause “with a political background…”

As is always the case, many leaders are arrested. Terror does not decrease but is rather on the increase. The Government explains this by alleging that the action of the Chinese and natives in the interests of China has given rise to great unrest in Indonesia itself. As a matter of fact, many strikes have broken out spontaneously. The dockyard-labourers and sailors of Semarang have gone on strike, the nursing staff in various hospitals as well as typographers refuse to work; in Priok, the Custom-house officers are on strike, and even in the remotest districts the peasants refuse to bring their produce to market.

At the place where the strikes and agitations are centred, a law has been passed prohibiting the holding of public meetings. The police of Semarang, who had been entrusted with the task of keeping the strikers under observation, joined forces with them with the object of exhorting better pay.

Soldiers and non-commissioned officers who were suspected of having connections with the Communists, were discharged from the army. Workers in private enterprises, as well as those in State employ, who dare to have any intercourse with a Communist or receive him into their homes, are dismissed.

The national Association of the Javanese Intelligentsia “Boedi Oetomo” tends towards the Left. The Indonesian Association of students in Holland was violently attacked by the bourgeois Press on account of its anti-imperialist politics.

The bourgeoisie is doing a rattling good business with the Colonies. One of their financial experts in a recent speech, said; “The returns from the plantations in the Dutch Indies, which are of as much importance for the money market and the stock exchange as they are for the industry of the homeland, have been of decisive importance in maintaining the stability of the Gulden during the post-war years.”

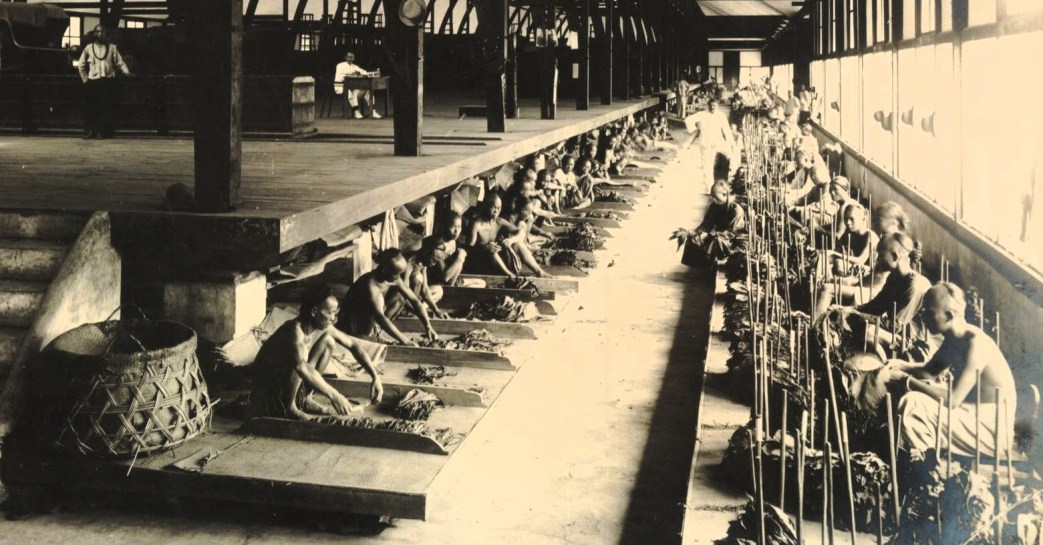

The tobacco harvest in Deli produced 81 million Gulden during the period from April 1st 1924 to March 31st 1925. The largest returns previous to that time had been 63 million Gulden.

Tea, coffee and sugar also command high prices. The high price of rubber was the cause of a conflict between the American capitalists as consumers and the English capitalists as producers. The Americans for this reason have again invested money in rubber plantations both in Indonesia and in the Philippines. The Dutch bourgeoisie is of the opinion that this need not alarm the English capitalist as it will take years before the new plantations yield any produce whilst, at the moment, England is in possession of three-fifths of the total production of rubber in the world.

Just as rubber caused a conflict between English and American capitalists, the same article was at the root of a conflict between the Government and the native population.

On Sumatra the natives themselves produce rubber and at the present time put on the market rubber to the value of over 80 millions annually. In this way they have become rivals to their foreign oppressors. As is always the case, the bourgeoisie is here again making efforts to undermine the native industry. Plans are being made with the object of bringing the native production entirely under European “control”. Measures are being taken for limiting their plantations. In these attempts however the bourgeoisie is faced by difficulties as the Djambil natives plant their rubber trees deep in the wildernesses of the country, where there is no possibility of “control” being exercised. The bourgeoisie nevertheless does not give up the fight.

The English are daily on the track of the rubber smugglers. on the coast of Sumatra. All coasting boats with a cargo of more than one kilo of rubber are confiscated.

The centre of the revolutionary struggle is lava. In accordance with the latest resolution of the Enlarged Executive, the Communist party has altered its tactics and adapted the propaganda more to the requirements of the peasants and petty bourgeois. The national bourgeoisie in Java is extremely weak because of the fact that national capital practically does not exist. The young generation of the intelligentsia tends towards. the Left and detaches itself from the petty bourgeois nationalists who make use of Islamism to bring about a counter action against the revolutionary people’s movement “Sarekat Rajat”. As a matter of fact, success has not yet been reached in welding the national and revolutionary movement into a united anti-imperialist Bloc. The existing tendencies however go to prove that a comprehensive organisation of all revolutionary groups is indeed possible.

Opposition reveals itself most openly among the proletariat, whereas the peasants, in spite of their great discontent, have up to the present participated too little in the struggle. The bourgeoisie is endeavouring to keep the peasants out of the revolutionary struggle and uses for its propaganda purposes the priests, who persuade the peasants that the communists and Sarekat Raja are carrying on a fight against religion. These lies, in time, are not without effect. Nevertheless the communists have a great influence over the peasants who appear in considerable numbers at the meetings of the Sarekat Raja which are conducted by the communists. The latest events have opened the eyes of the Chinese to the fact that the Dutch bourgeoisie is working hand in hand with the English bourgeoisie. As the result of this, the Chinese and the Indonesians have joined forces and the fight against imperialism has thus gained in strength. The Government has expelled some Chinese editors of Chinese newspapers and has thus added to the number of its enemies.

It is the task of the Communist Party to unite these enemies of the bourgeoisie into an anti-imperialist fighting line.

Labour Struggles in the East Indies.

Strikes are spreading in the East Indies. More and more printing works are closing down. The movement is no longer limited to Java but is spreading to Celebes and Sumatra. In Semarang almost all the workers in the printing works are on strike. In other places, the typographers are on strike, as for instance in Surabaya and Makker (Celebes). As a result many bourgeoise papers cannot appear; others are appearing in a smaller form. Conflicts have further broken out in metal works, sugar and opium factories, hospitals and many other concerns. The struggle in the harbours of Semarang and Batavia has been going on for some weeks and in Semarang is spreading further and further.

Only a small part of the workers is organised; most of the workers first joined the organisation during the strike. In consequence of the lack of a good organisation, the strike cannot be carried on intensively everywhere. The bourgeoisie in the East Indies is using Europeans, especially those who are out of work, as strike-breakers.

The strikes are, as a rule, the result of a refusal to increase wages. In some cases whole staffs of workers have gone on strike because one of their comrades was dismissed. Finally, in Semarang, some sympathetic strikes with the dockworkers are to be reported.

Apart from the intensification of the conflicts, there is a revival of political interest among the peasants, who are attending the communist meetings in large numbers.

Among the persons living on private landed-property, there is a state of ferment. The landowners, who are assisted by the police in the forcible collection of their rent, are squeezing them dry. The conditions which prevail are absolutely feudal.

The Railwaymen’s Union, which suffered a defeat in a strike a few years ago, has so far regained its strength, that the bourgeoisie has to reckon with it. The police and the railway directors are trying to suppress the congress of railwaymen which has been planned, by forbidding assemblies and refusing leave.

Among the soldiers also, a spirit prevails which is alarming for the bourgeoisie. Army Headquarters has issued a list of those publications which soldiers are forbidden to read, among them being the publications of the R.I.L.U. and of the “Inprecorr.” The bourgeois Press urges the army chiefs to increased vigilance because, so it maintains, there are close connections between the soldiers and the communists. Demands are also made that the civil population should be forbidden to read certain publications.

The bourgeois Press is conducting a furious campaign against our Comrade Darsono. He was arrested on the charge of having been a leader in the strike movement. The bourgeoisie is trying to enforce his banishment. The editor of the communist paper, “The Proletarian”, has also been arrested.

The legal authorities are trying, in common with the police, to intimidate the population. In Soemedang 163 revolutionaries were dragged before the Court; 41 of them were sentenced to periods of imprisonment up to four years. They were charged as a result of a conflict with the police, to which they were provoked nine months ago by a band calling itself “Sarekat Idjoe” (The Green Association”), which, in the service of the Fascists, attacks and removes communists by night.

Furthermore, 31 members of the People’s Association. “Sarekat Rajat” were sentenced because they held an assembly without having obtained permission.

The behaviour of the police is becoming more and more brutal. They follow the directions of the capitalist Press which is always clamouring for the exercise of more force.

In spite of all this, the revolutionary development in the East Indies cannot be arrested by the power of the Government.

The revolutionary movement in China had the effect of establishing fraternal co-operation between the East Indies and China. The Government is deporting revolutionary Chinese teachers and journalists. This however has only resulted in many Chinese newspapers, which previously held a more or less neutral attitude towards the Government, being now in sharp opposition to it. They are now openly making propaganda for Sun Yat Sen’s ideas and have declared their sympathy with the Soviet Union.

In this way, constantly increasing numbers are being drawn into the anti-imperialist struggle in this important colonial territory. All the groups of eastern peoples, living in the East Indies, such as the Javanese, the Sumatrans, the Chinese, etc., are expressing their sympathy with the struggle against Anglo-American imperialism in China. This sympathy brings them into conflict with the Dutch bourgeoisie and intensifies the antagonism between the latter and their colonial slaves.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n73-oct-08-1925-inprecor.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1925/v05n74-oct-15-1925-inprecor.pdf