The Popular Front-era, in which Communist, Socialist, and bourgeois Radicals ruled France saw no significant change in colonial policy, let alone independence. For Communists and revolutionaries in France’s colonies, the Popular Front naturally created expectations, soon to be dashed. Albert Weisbord looks at the situation in ‘Indo-China,’ where the Popular Front, forming alliances with bourgeois nationalists and the independence movement, necessarily came into conflict with the policies of the Popular Front in metropole France, also in alliance with bourgeois forces, but opposed to independence.

‘French Imperialism in Indo-China’ by Albert Weisbord from Class Struggle (C.L.S.). Vol. 6 No. 7. November, 1936.

Once the revolution reaches the point of civil war in the imperialist countries, the colonial question is bound to become a decisive one. Will anyone deny that it was with the aid of the Moroccan troops that the Spanish “rebels” were first able to launch their attack or that the use of the Moors has been decisive in enabling them to continue their aggressions? It is the Spanish Revolution that poses this question first as one to make or to destroy the proletarian revolution. Sooner or later, this question must come to the fore in France also.

The only way the workers in the imperialist country can win the colonial peoples as allies in their struggle is to demand and fight for the freedom of the colonies. Just as the existence of the mother imperialist country depends upon the revenues sucked like so much blood from the veins of the colony, so indeed must the maintenance of the revolution for such countries as France, England or Spain depend upon setting free the colonial masses. Can anyone imagine a Workers’ State owning colonies? This is, however, no question of morality or abstract economics. In the life and death struggle between the capitalist regime and the budding workers’ power, if the colonies are not won to the workers’ side, they will become vast reserves for the reactionary Fascist forces to draw upon, to the defeat of the workers both in the colonies and in the mother country.

So far, the experience of Spain and France would seem to show that this question has not been in the least understood. It is the nationalism of the Second International that prevails. The Leninist theses of the Third Congress of the Third International are buried so deep that no thought of bringing the demand of freedom for the colonies to the fore ever ruffles the pages of L’Humanite nor indeed, so far as we can see, agitates very much even the advanced groups of Spain and France. Yet in this colonies themselves the advent of the People’s Front in France and the events of the civil war in Spain must have aroused deep agitation and hope. We quote to this effect from La Lutte, an Indo-Chinese paper in the French language, to which, by the way, we are indebted for the descriptions of life in Indo-China which follow: “We, the colonial peoples, deprived of all rights and liberty, are awaiting a change in our conditions. …The victory of the People’s Front in France will open up a new era full of promise and hope for the colonial peoples.” (April 22, 1936)

But in each subsequent issue of the paper, we find only the failure of these hopes recorded as the months of the People’s Front government go by. Evidently, the sufferings of the colonial masses are still a matter of indifference to the worker in the industrial country. So wrapped up is he in his own national struggle that he does not see that his conditions, which are so wretched as to drive him to revolution are still miles beyond the darkness of such places as Indo-China. Nor does he realize that these same oppressed peoples can strike a body blow at that very power he is trying to defeat, if he will but help them in their struggle.

The French colonial system is a classic one in the sense that all its enormous territories including the African colonies, Madagascar, Indo-China, French Guiana and other American possessions, have been kept at the most backward possible level. Here is a country of only a little over 210,000 square miles in area, possessing colonies that total nearly five million square miles. The imperialist country is here seen as the apex of a pyramid which has as its base a vast mass of over 60 millions of people, most of them belonging to the colored races. In none of these colonies has industry been developed to any considerable extent. They are sources of raw material and especially of revenue which is squeezed out of the wretched bodies of natives who are forced to live in ignorance, poverty and terror.

The conditions in Indo China, the most important of the French colonies from the point of view of population and trade, may be taken as typical of those prevailing in any colony. With this difference, however, that Indo-China is far more backward than such colonial or semi-colonial countries as India or China. There at least industry has been allowed to thrive up to a certain point; there the working class has reached a degree of strength to organize and even force some concessions for itself; there the national revolution has been carried on for generations and has compelled a certain amount of bourgeois development to be tolerated within the country. But the French colonies suffer from being the dependencies of a decadent country, a country living on revenues rather than on the expansion of industry; they are victims of economic and social stagnation as well as of terrible oppression.

French Indo-China, in a total area of about the size of Texas, comprises six provinces, of which the smallest, KwangChow, is leased from China. Cochin-China (ceded to France in 1862 by the King of Annam) has the status of a colony, the other four provinces (Annam, Cambodia, Tonkin and Laos) are kingdoms under a French protectorate. The nationalities included are Annamite, Chinese and Hindu as well as a small number of French and other Europeans. Practically all of this country is given over to agriculture (rice, rubber, and cotton plantations and small economy) or to jungles. There are few cities, and no city of great size. Saigon, the seaport of Cochin China and former capital, has 123,291 inhabitants. Of about the same size is the present capital, Hanoi, in Tonkin. Roads of a sort have been built, and some railroads, so that the raw materials and products may be exported. The industries are coal-mining in Tonkin especially (1,680,000 tons of coal were produced in 1932), some sugar refineries and distilleries, saw mills, match and glass factories, tobacco, cotton and paper manufacture. In Laos there are extensive teakwood forests, and some gold, tin and lead is produced. The working class of Indo-China totals about two million in a population of about 21 million. With the exception of a small percentage of natives surrounding the native kings and part of the government apparatus as petty officials, the vast mass of the population are either serfs or poor peasants raising a little rice and vegetables and catching fish for a living. The country is under the jurisdiction of a French Governor-General (R. Robin at the present time) with French governors in the provinces, supplemented by figureheads of native kings. The whole government apparatus down to the lowest native official is corrupt, and graft is rampant.

Most of the people enjoy no civil rights. The natives are subjected to a constant hounding by the ever-present officials. Especially the collection of taxes burdens them. There is a yearly personal tax upon payment of which the native is given a card. Woe to him who cannot show his card, the receipt for his tax! Periodically the local police round up all the people they can find in the market or other public place, and thrust into prison such as cannot produce their card. Or as an alternative, in districts where the government is constructing a road or other public works, the poor wretch without a card may have the privilege of working off his tax. To quote from the pages of La Lutte (The Struggle), faithful chronicler of the abuses of Indo-China: “…In VinhLong, along the colonial highway, the Administration is digging a long canal. Here, under the leaden sun, a crowd of coolies are toiling in the mud, their heads barely protected by a poor hat of palm leaves. They are paid thirty cents a day, the Administration keeps 20 cents for the payment of the personal tax. At the end of a month’s time, the coolie will have worked off his tax; in reality he will have earned ten cents a day for a ten-hour day’s work. …Even this forced labor is a favor. It provides a means of liberation unknown in other places where the man-hunt fills the prisons and police stations.” Not merely is the penniless native subject to imprisonment for the non-payment of his tax, but he is fallen upon and beaten barbarously by the “guardians of the peace” who arrest him.

As for the conditions of life of the peasants, the following story will give an idea (from La Lutte, June 24, 1935):

“The other day at Bung (Thuydaumot) I met an extremely poor peasant, by the name of Nguyen-van-Buu. He told me all his troubles. As I listened, I seemed to be transported into an unreal world. “He owns a bit of land, a tiny plot. It is an ungrateful soil like all that part of eastern Cochin- China. The whole year he digs this land, his only resource. He alternates the raising of rice and of vegetables. His average harvest is about 40 gia, that is, about 1,600 litres of paddy, worth about 20 piastres (Note—the piaster in 1930 was worth 10 francs). “This rice must do after a fashion to feed a family of six mouths, he, his wife and four children. His wife sells salted fish, or vegetables, anything she can get. After paying the taxes, her earnings are ten cents a day. Even if she can work a whole year, she does not earn more than 30 piastres a year.”

The result of such poverty is that the poor peasants everywhere fall victim to the loan sharks, the curse of every poor countryside. Once in debt, it is practically hopeless ever to get out of it. The debtor is at the mercy of the money-lender as well as of the legal authorities who support him. The poor quality of the soil as well as the backward methods of cultivation make famine a frequent occurrence here, carrying off thousands in North Annam particularly. As for these who live and till the land of others, the serfs, they have no rights at all. If it is found that a serf has erected a new hut of straw for himself, even though the old one was burned down or destroyed, he can still be ordered to tear down his house, if he has not obtained the necessary permission from the local authorities to build it.

On the plantations the exploitation is unspeakable. The working day is 10 to 12 hours; the wages of 20 or 30 cents leave the coolie penniless when he gets ready to go. More often than not, however, he is bound by contract so that he cannot leave until death by fever or overwork claims him. As for the public works which the government undertakes, it is not an exaggeration to say that thousands of natives literally pay for these with their lives. In some provinces such as Laos, where a new road is now under construction, the natives are compelled to give the government 16 days work in addition to paying their personal tax. Only by paying four piastres can this forced labor be escaped. But in Laos the agricultural worker earns only 12 piastres in a whole year (a woman worker only 6) so that very few can pay their way out.

The natives must walk 100 or 150 kilometres through the dense forest to reach the work camp. There, instead of 16 days’ work, they find tasks assigned them that will take a month or six weeks. To protest would mean immediately to be thrown into prison. Sometimes the victims risk everything and flee, crossing the frontier into Siam. Theoretically the coolie is paid 25 a day, out of which he must provide his own food. But he is at the mercy of the contractor. The latter brings his relatives to the camp where they set up commissaries and charge what they please for the coolie’s rice and dried fish. The work consists in felling age-old trees of great size, and moving tons of earth and rocks. The sleeping quarters are in the dank forest with no protection from the swarms of mosquitoes, carrying the germs of swamp-fever to which the workers, underfed, overworked, without suitable drinking water, succumb like flies.

Wherever one looks, whether to the railroad workers, to the dock workers, or to the factories, there is the same savage exploitation. In the factories, there is unlimited child labor and night work of both men and women. Sanitary precautions or compensation for accidents are unknown. Children of 8 to 14 years have had their arms crushed in the sugar cane factories. For a mangled arm, one worker was given three piasters by his employer…about $2. …But after all, where life altogether is so cheap to the exploiters, need we wonder that one arms costs only $2?

All the abuses that prevail have not been endured without protest. In spite of the peaceful character of the people, there have been many rebellions in Indo-China, the last, in the years 1930 to 1933, having been bloodily repressed. One city was bombarded, machine guns were used as well as all ordinary means of brutality. The jails were filled to overflowing. Most of the rebels condemned at that time, as well as many arrested since for organizational activity or for real or suspected seditious opinions, still remain in prison. In Poulo-Condore, a penal island prison are kept a few thousands of political prisoners under unspeakable conditions.

These unfortunate men are compelled to work as much as fifteen hours a day at hard labor. They are fed the worst quality of rice mixed with gravel, boiled weeds in place of vegetables, and rotten fish which stinks to heaven. Tuberculosis, dysentery and scurvy are common. Not merely this, but the helpless prisoners are visited with punishment upon the least or no provocation. The sadism of the keepers vents itself sometimes in orgies of beating, kicking and blows with clubs lasting for hours. Death has resulted for some prisoners for these frightful attacks; others will never regain normal health. In Saigon at the police station is a torture chamber to which any militant who is arrested is taken and subjected to “treatment” in the hope of forcing a confession from him involving his friends. In order to leave no marks on the victim, modern methods are used such as the electric current and “gizzard twisting.” Once released, the victim is a nervous wreck for life.

In spite of the relentless persecution by the authorities, in spite of the prohibition of meetings and of the right of organization, nevertheless there have taken place many strikes both on the plantations, in the factories and in the prisons. The struggle has been, however, sporadic rather than continuous, and strong working class organizations have not as yet been built. There is an Indo-Chinese Communist Party and even a group of Trotskyists and of internationalist communists. We do not know the policies of these groups, but we are safe in saying that their members are willing to suffer heroically for the freedom of their people. In fact, a secretary of the C.P. has recently died as a result of the terrible tortures inflicted upon him when arrested. Opposition to the government centers to a great extent around certain newspapers such as La Lutte and others in the native language. These papers expose the abuses and advocate as radical a policy as they dare.

The election of the People’s Front government in France meant a great awakening for the downtrodden people of Indo-China. Not daring to hope for freedom, they still believed that some alleviation of their conditions would be granted, that at least the political prisoners would be freed and that some of the codes for workers in France, such as the 40 hour week, would be applied to them. The radical papers like La Lutte have carried on a constant agitation and have petitioned the central government in France. The appointment of a former militant socialist, Marius Moutet, to the post of Minister of Colonies aroused more hope than they dared express.

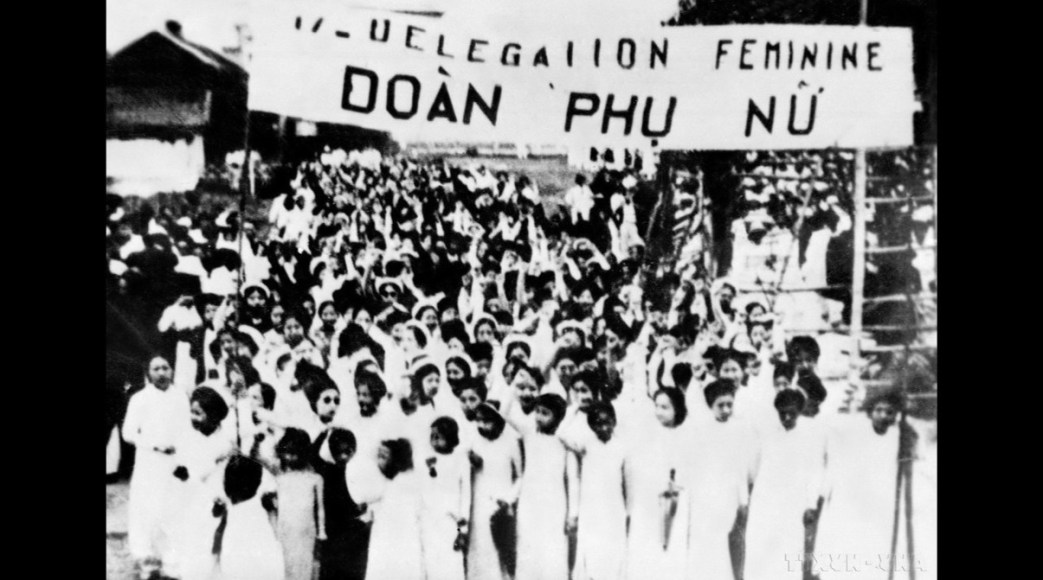

But what has been the outcome? The only tangible move of the Blum government for Indo-China has been … to promise a Commission of Inquiry. Even this crumb has been taken very seriously. A demand has been raised for a national Congress to formulate the demands to be placed before this Commission of Inquiry when it comes. A provisional committee has been formed which has met. It is no easy matter to organize such a congress in a country where all rights are forbidden, and where everyone is so poverty stricken and illiterate. In order to further the calling of the Congress, Committees of Action are being formed on all sides. These are little groups of workers, of peasants, or of intellectuals who get together in threes and fours or perhaps half a dozen at a time to discuss their grievances, to seek out the causes of their oppression, and to send in demands to the Congress. All this activity has been within the realms of legality. The committees are never more than 19 in number, for if they were 20 it would be called a “meeting” and would be illegal.

What has been the response from France, from the great liberating People’s Front government? Two telegrams have been sent to the government in Indo-China by Marius Moutet. The first was a somewhat wordy document giving publicity to the Commission of Inquiry and asking cooperation in putting over this move harmoniously. Guardedly it cautioned against agitation or demonstrations which would make matters difficult. But the second telegram was much more to the point. It came after the Committees of Action had spread like wild fire and were becoming one of the biggest popular movements these colonies had ever seen. It read as follows: “You will keep public order by all legitimate and legal means, even by pursuit of those who attempt to disturb it should this seem necessary.”

The authorities have not hesitated one minute to use this authorization and everywhere there have been raids, arrests and persecutions of those who were active in the Committees of Action and the National Congress. A fake Congress was hastily organized, with the members of the provisional committee for the real congress notified that they must send in their demands in four days, and must dissolve their organization as well as the committees of Action. Thus by violence and ruse everything is being done to break up this real people’s movement which is putting forth nothing extreme, but is asking only the most elementary rights of freedom of the press and assembly, the right to organize and strike, amnesty for political prisoners, relief for the unemployed, etc.

Now indeed have the Indo Chinese militants become disillusioned with the People’s Front. Now do they see that not merely is no demand for their freedom raised in France, but that entirely the old policy of repression, the boot, the club and the machine gun is the People’s Front policy for the colonies. And they are saying that they must continue the struggle alone. Yet this conclusion of disillusionment is not correct either. The colonies must have the help of the workers of the mother country, but they will get this help only when the workers there have learned to break the discipline of the parties they have now and to set up fresh organs of struggle that will really join hands with the colonial people and fight for their freedom as for their own.

The Communist League of Struggle was formed in March, 1931 by C.P. veterans Albert Weisbord, Vera Buch, Sam Fisher and co-thinkers after briefly being members of the Communist League of America led by James P. Cannon. In addition to leaflets and pamphlets, the C.L.S. had a mostly monthly magazine, Class Struggle, and issued a shipyard workers shop paper,The Red Dreadnaught. Always a small organization, the C.L.S. did not grow in the 1930s and disbanded in 1937.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/the-class-struggle_1936-11_6_7/the-class-struggle_1936-11_6_7.pdf