In the Socialist and later Communist Party since 1914, Marxist intellectual Joseph Freeman was a central figure in the literary Left as writer, critic, founder and editor of both the New Masses and Partisan Review. Here he offers a major survey of U.S. writers of the 1920s, from the world of popular magazines and pulp fiction, to the ‘Wilsonian Liberals’ and the later-1920s conservative and left-wing reaction to them.

‘Notes on American Literature’ by Joseph Freeman from The Communist. Vol. 7 Nos. 8 & 9. August & September, 1928.

WHEN people speak of “Literature”, they generally refer to belles lettres, especially to the better type of novel, short story and poem. In this sense, “literature” is of little consequence in the life of the American masses. There is no comprehensive study of what the workers and farmers of the United States read, but the fact is that the overwhelming bulk of printed matter in this country does not consist of belles lettres. Most residents of Main Street have never heard of Sinclair Lewis and most workers are unfamiliar with Upton Sinclair’s name. The chief ingredients of the people’s “artistic life” are not belles lettres but newspapers, cheap magazines, radios, phonographs and movies. Europeans who read fairytales about the “land of boundless possibilities” often forget that the majority of Americans are absorbed in the struggle for bread and butter. A conservative economist estimates that 80 percent of the population make only a little over their expenses.

This hardly leaves room for the “life of leisure and imagination” out of which literature is supposed to have flourished hitherto. Workers and farmers who have the time and inclination for more than newspapers, magazines, movies and jazz, read adventure novels or sentimental romances like the books of Zane Grey and Harold Bell Wright. The literature of Dreiser, Lewis, Cabell and Anderson to which critics refer forms a tiny island in the vast sea of American printed matter.

A thorough analysis of the United States as reflected in the written word would involve a study of a colossal industry which is based on mass production, division of labor, a highly developed technique, standardization of idea and form, and gigantic advertising campaigns based on effective psychologic principles. Even without such a study, however, it can be noted that literature, in the sense of belles lettres, plays an insignificant role not only in the life of the masses but even in the life of the big bourgeoisie and the professions. There is no writer in the United States today whose position is in any way comparable to that of Gogol, Dostoievsky or Tolstoy in their time; nor has any American writer the same weight in public affairs as Bernard Shaw in England or Romain Rolland n France. An infinitesimal part of the American people reads the American novelists and poets, and “literature” is a decidedly minor cultural -factor in the land of radios and Fords. If there is any point to the intelligentsia’s satire against the babbitry it is precisely that the American businessman despises an art which at one time played a significant role in European culture.

On the whole, Americans do not look to novelists and poets for guidance in life, profound insight into the human mind, or the imaginative solution of social and personal problems. The big bourgeoisie relies rather on science and technique; while the middle classes and workers seek it in non-literary publications like the Saturday Evening Post, the American Magazine, Psychology, and Popular Science Monthly; and in the works of Elinor Glynn, Gene Straton Porter and Will Durant, whom no serious literary critic includes in his estimates. The labor movement finds itself even less in belles lettres. If the American trade-union leaders, socialists and communists are in any way affected by the novelists and poets, they fail to show it. America has no Nekrassov or Gorki; and the revolutionist, like the bourgeois, at bottom despises a form of expression which cannot have any noticeable influence on production, wages, or political alignments. The “good writers” find their readers chiefly among the middle-class intelligentsia, women with a longing for “culture,” students, Bohemians, and other writers.

Several critics are acutely conscious of the feeble position of American belles lettres, though none so far has shown with any thoroughness the connection between this feebleness and the economic milieu in which America belles lettres live. A study is needed of the overwhelming influence on the “better class of books,” of such phenomena as mass literacy, multiple presses, high power advertising, fat royalties for the vulgarisation of ideas: in short, the “rationalization” of the publishing industry. Certain American critics have observed the pressure of commercialism on literature. Van Wyck Brooks has written a book showing how the desire to become a millionaire “like other people” crippled Mark Twain’s genius; and another book showing how the shallow “spiritual life” of America drove Henry James to England and sterility. There is also the case of Jack London, who despised himself as a writer in a milieu of colossal action; and there is the complaint of Upton Sinclair in Mamonart and Money Writes that sooner or later the passion for money and power drives American writers to sell themselves outright to the bourgeoisie. The attitudes of these men are based on ethical assumptions. For them it is not primarily a question of a social-economic organism moulding the minds and actions of writers, but merely of the “moral weakness” of writers in surrendering to the desire for money and power.

In other quarters, however, there is a growing consciousness of the effect on belles lettres of the spread of science and technology. It is becoming clearer and clearer that the intellectual youth of America, whether Left or Right politically, has a greater regard for the psychology of Freud, Watson and Pavlov than for the psychology of the best American novelists; that sports furnish an outlet for energies which in other times and lands express themselves in artistic forms; that the aviator Lindbergh and other “heroes” featured in the press capture the popular imagination far more than any character in fiction or poetry; and that belles lettres remains the work of a small and not very influential class.

This is perhaps true today not only of the United States but of nearly every country in the world. A New York literary publication recently printed an article by the French poet Paul Valery in which he said that perhaps with the old arts succumbing before science and the machine, literature may become a mere sport, like tennis or golf.

With such considerations in mind, it will perhaps not be necessary to add that these notes deal with a slight fragment of American literature in the widest sense of the term. The vast bulk of printed matter, perhaps more important from a sociological point of view, must be disregarded. Here reference is made to a few writers of belles lettres in so far as they reflect, from a distance, certain social tendencies in American life. Naturally, a consideration of the social aspects of any art does not exhaust the subject. American literature can be best understood in the light of American economics; yet this would reveal only the anatomy of literature; its feeling would still be lacking, and the flavor of experience which literature gives us—as distinct from information, which is the business of science—would be lost altogether. Here, too, however, the tremendous production and consumption of printed matter in the United States is of prime importance. The greatest wealth the world has ever known is concentrated in America, and the consequent “free energy” is reflected in belles lettres, as well as newspapers and magazines. Novelists, biographers and “philosophers” who have the good fortune to become best-sellers make money far beyond the expectations of even the greatest European talents. Successful American authors do not have to sell their private libraries like Andre Gide, and successful European authors like Emile Ludwig and Count Keyserling, after achieving fame on the continent can cash in on it in New York.

THE “WILSONIAN” LIBERALS

The writers who reflected the deflated “liberalism” of the Wilsonian era have reached their zenith; many of them have passed it. No new developments can be expected from most of them, though they continue to create. Dreiser has published a series of articles, most of them friendly, on his recent visit to the Soviet Union. It is said he plans to issue a book of stories about women, much like his “Twelve Men,” but his philosophy, individualistic through and through and permeated with the raw determinism of nineteenth century Darwinists, cannot go much further than the American Tragedy. Sinclair Lewis has just published a brilliant satire on the babbitry entitled “The Man Who Knew Coolidge”; but this is an extension of the mood and method of Main Street and Elmer Gantry, and merely carries to a more precise point the post-war dissatisfaction of the liberals with the crudeness of the American scene. The Wilsonian poets—like Carl Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters and Vachel Lindsay—are silent as poets, though Sandburg continues to publish a column of political and economic gossip in a Chicago newspaper, and has issued an excellent collection of American folk-songs.–The Mencken vogue seems to be waning; and of him, too, it can be said that he has no new word beyond his contempt for the American masses, for democracy, prohibition, and the Methodist church. If he has changed at all, it is in his cynicism about university professors. The American Mercury which he edits, carries a disproportionate number of contributions by academic gentlemen.

Sherwood Anderson has quit publishing novels and stories altogether. He has retired to a small town in the mountains of Virginia where he owns and edits two weekly newspapers. One of these is Democratic, the other Republican. A great artist like Anderson is able to edit them both at the same time because he has despaired of solving the problems of industrial civilization, and because there is little difference between the major bourgeois parties. In his earlier books, like Winesburg, Ohio, and Marching Men, he depicted the social and psychological tragedies of American petit-bourgeois life under the pressure of monopoly capital. Later he wrestled with the problems of machine civilization. In his two autobiographical works A Story Tellers Story and Tar he betrays a deep-rooted fear and hostility toward the American machine world, and a longing for the “idyllic” time of handicrafts and “simple” villages. Despairing of the “superficial” culture of big cities, he retired to a southern village and took up the life of a country editor, supporting in one newspaper the activities of local Democratic politicians, and in the other of local Republican politicians, writing gossip about local farmers and small merchants and instructing them about “life.” Here are some passages from his sermon on “Mind and Morals” which appeared in his Democratic newspaper:

“The whole object of education is, or should be, to develop mind. The mind should be a thing that works. It should be able to pass judgment on events that arise, make decisions…Morals also are largely a matter of brains. We are all driven through life by lusts. Why deny it? There is sex lust, food lust, lust for luxuries, for power. The man with good brains simply recognizes his lusts as part of his life and tries to handle them. If he is an artist he tries to divert the energy arising from his lusts into channels of beauty…You have a lust for money or power. To get it you will do anything. You see plenty of such men—in politics, for example. Men who will lie, cheat, steal, sell out their friend—politically, and who in other walks of life are fair enough men. Well, that is just a form of lust, too. It is political drunkeness. There are various kinds of drunkeness in this world…Take the matter of drink…I should think a man of good sense would see it as not a moral question at all. It is a matter of good sense. If a man cannot drink without making a fool of himself and hurting others he should let drink alone. He should let anything alone he can’t handle…I have learned to look at my body as a house in which I must live until I die. I want it to be a fairly clean and comfortable house …A little decent paganism wouldn’t hurt most of us. We ought to try to be less mixed about morals and a bit more clear about mind. A little more decent faith in the house in which we live—the house that is the body—less thinking about death and more about living, more self-respect.”

THE NEW BEST-SELLERS

The lists of best-sellers are no longer filled by the names that were familiar five years ago; and both on the Left and on the Right (these terms will be used throughout as political categories) there is open revolt against the writers and critics who expressed the despair and disillusion of a period now definitely dead. One of the noteworthy aspects of current American literature is the tremendous sale of non-fiction. The Outline of History, published by H.G. Wells several years ago, was followed by outlines of science, art, literature and what not. One ambitious minor novelist has written an Outline of Human Knowledge, which attempts to cover all intellectual spheres, and is even more remarkable for its errors than its scope. There has been a flood of biographies dealing with European and American figures as well as of popular histories and scientific works. American translations of Emil Ludwig’s biographies of Wilhelm II, Napoleon and Bismarck have made him a rich man, and, during his recent visit to New York, a literary lion. Two of his biographies are at this moment among the twelve best selling non-fiction works in the United States. The other ten are:

Trader Horn, an alleged autobiography of lurid and incredible African adventures, by Aloysius Smith, an old man of uncertain age who has made a fortune out of his one book and was feted like a hero by the New York intelligentsia; The Royal Road to Romance and Glorious Adventure, by Richard Haliburton: these are two “thrilling” travel books; We, an “autobiography” by the aviator Lindbergh, dealing chiefly with his transatlantic flight; What Can a Man Believe, an attempt to explain Christianity in American business terms by Bruce Barton, an advertising expert who discovered that Jesus was just like a member of the Rotary Club and the bible like a safety-razor advertisement; Revolt in the Desert by the adventurer Lawrence who was the agent of the British government in Arabia during the war; The Companionate Marriage by Judge Lindsay, a jurist who is attempting to liberalize the sex and marriage laws; and two books by Will Durant: the Story of Philosophy and Transition.

“PHILOSOPHY” OF THE PHILISTINE

The last author deserves a few words. The popularity of his book on philosophy, which made him rich and famous overnight, reflects the present temper of the American petit-bourgeoisie. When due allowance has been made for the power of advertising and salesmanship—often the motive power behind a book’s popularity in the United States—there remains the fact that no “philosopher” has so persuasively stated the self-complacency of the prosperous philistine. Durant began his career first as a Jesuit student, later as an anarchist. For ten years he lectured on philosophy and literature in the East Side section of New York, inhabited chiefly by Jewish, Italian and Russian workers. Philosophically he has always been superficial and eclectic. During the war, after coming under the spell of John Dewey, he wrote a book on Philosophy and the Social Problem which made no great stir. There he urged the formation and training of a ruling class selected on the basis of intellect and knowledge. It was only two years ago, when the passion for biographies and outlines became popular, that he really found himself.

His Story of Philosophy is marked chiefly by anecdotes from the lives of the philosophers and by a vague skepticism: The book had a tremendous sale. Lavish advertising by his publishers convinced well-to-do housewives, immature students, and stenographers, all thirsting for “culture” to be achieved at American speed, that for five dollars they could know all about philosophy from Thales to Bertrand Russell in the time it takes to read a book of several hundred pages. Durant became not only a rich man but an important “figure.” Newspapers and magazines invited him to express his opinions on current questions. One newspaper bought his services as special correspondent at a sordid and sensational murder trial, and soon afterward published his “Outline of Civilization.”

Meantime Durant found himself in the predicament of all successful American authors. He became a slave of “mass production.” Having told the life-story of other philosophers, he turned to his own life-story and produced the “spiritual autobiography” Transition. This book, which is among the best sellers, is an unbroken story of disillusion with a note of sweet acceptance at the end. Durant tells how he was disappointed in turn by Christianity, socialism, anarchism and even philosophy. It was all vanity of vanities. His one consolation at present is his wife, and his little daughter Ethel; they alone, particularly little Ethel, make life intelligible and supportable. Lest it be thought that this is a caricature of Durant’s thought, here are some passages from his article in the Hearst Press in which this “philosopher” discusses character and the “meaning of life.”

“The ideal career,” Durant says, “would combine physical with mental activity in unity or alteration. This is a luxury which few of us can afford. But let us at least mow our lawns and clip our hedges and prune our trees, and let us make any sacrifice to have a lawn and hedges and trees. Some day perhaps we shall have time for a garden…To seek health and strength we may need a new environment; and it is always a consolation to reflect that though we cannot change our heredity we can alter our environment. Are we living among unclean people or illiterates concerned only with material and edible things? Let us go off, whatever it may cost us, and seek better company…Better to listen to greatness than to dictate to fools. Caesar was wrong: it is nobler to be second in Rome than to be first among barbarians.” (Italics mine.—J.F.).

Hope of entering the elegant and exclusive ateliers where they can be “second in Rome.” But to the philistines of the middle-class it must be a great comfort to see that a famous “philosopher” who knows all about Spinoza and Kant has at last prostrated himself before the shabby idols which they have worshipped so long. Durant reaches his apotheosis in his views on marriage:

“Marry! It is better to marry than to burn, as Holy Writ has it, and enables a man to think of something else…We realize that however different the skirts may be, women are substantially identical…And so we become moderately content, and even learn to love our wives after a while…It may be true that a married man will do anything for money (even sell his “philosophic” intellect—J.F.) but only a married man could develop such versatility.”

This “thinker” has now the largest audience in the United States of any man who calls himself a philosopher, chiefly because he flatters the philistines’ self-respect.

This advice cannot be of much use to the 30,000,000 industrial workers and 37,000,000 farmers of the United States, who are in no position to “go off” and listen to “greatness,” and who have little.

II.

PROPHETS OF THE YOUNGER GENERATION

GORHAM B. MUNSON, a young critic at one time connected with the aesthetic group of the Dial, has published a series of literary essays outlining the attitude of the “younger generation” of American writers. He divides contemporary American writers according to a chronological pattern and finds that they fall into three generations.

The Elder Generation is represented by two conservative critics, Professor Paul Elmer More and Professor Irving Babbit of Harvard University. The Middle Generation is represented in aesthetics by J.E. Spingarn; in fiction by Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson; in the drama by Eugene O’Neill; in poetry by Carl Sandburg and Edgar Lee Masters; and in criticism by Van Wyck Brooks and H.L. Mencken. The Younger Generation in Munson’s pattern is represented in fiction by Ernest Hemingway and Glenway Wescott; in poetry by E.E. Cummings; in criticism by Kenneth Burke.

He finds that the Elder Generation is characterized by extensive scholarship, hatred of romanticism, classical religion and classical humanism, and conservatism in general outlook. “The Middle Generation, he says, was rebellious and emotional; it favored socialism and other humanitarian movements and went in for the “craze” of psychoanalysis. Its novels were naturalistic and its criticism impressionistic. “The Younger Generation is suspicious of the enthusiasms of the Middle Generation, and has raised the question: “Are there any new ideas which could be introduced into the minds of our writers, ideas of another order than those to which they are now accustomed, which might have the effect of stimulating American literature to rise to a new level?”

Munson undertakes to answer this question by proposing the “idea” of a quest for “perfection in both literature and character of living.” In this he makes a healthy departure from the Wilsonian group, many of whom tended to set art beyond life as a city of refuge. As part of his “new” program Munson urges “the growth of a profound and embracing skepticism” and the cultivation of “common sense,” which is a decision common to the intellect, the emotions and the practical instincts.” He defines this idea further as “totality of view, impartiality, and purposiveness of writing and reading,” and acknowledges the intellectual leadership of Professors More and Babbit, whom he calls “the two most mature intellects in American letters.”

Professor More is an old critic who edited the Nation some twenty years ago when it was a reactionary journal. He has published a number of volumes on literature and philosophy under the common title “Shelbourne Essays.” Munson describes him as a “Platonist with a Victorian education” and a “religious dualist.” We should describe him as a mystic. More believes that “we are not alone in the universe,” that “forces beat upon us from every side and are as really existent to us as ourselves; their influence upon us we know, but their own secret name and nature we have not yet heard…” He therefore urges that we “hold our judgment in a state of complete suspense in regard to the correspondence of our inner experience with the world at large, neither affirming nor denying, while we accept honestly the dualism of consciousness as the irrational fact.”

More’s metaphysic formulates clearly the “profound and embracing skepticism” which Munson attributes to the younger generation of American writers, and perhaps many of them even share his motives, if not his formulation, when he says that “submission to the philosophy of change is the real effeminacy; it is the virile part to react.” In More they find a Platonist who rejects the Utopian implications of the Republic and a religious dualist who discards the “love” of Christ, giving them only a lofty and erudite snobbishness.

Professor Babbit, the other maitre of the younger conservative writers, is more earthly. His first book was a practical attempt to solve certain educational problems which confronted him as a teacher of literature. His second book The New Lookoon attempts to make precise distinctions among the arts. This was followed by Masters of Modern French Criticism, which deals with the general problems of literary criticism and fires the first shots in his war against the romantic spirit in art and life. His fourth book Rousseau and Romanticism analyses the problem of the imagination, and, from an attack on the romantic imagination, proceeds to certain political conclusions which are elaborated in his latest book Democracy and Leadership.

We have here, then, a practical imagination which moves logically from education and literature to politics and economics. The attitude Munson admires in Babbit is his conviction that art and literature “should stand in vital relation to human nature as a whole and are not to be considered as forms of ‘play’ after occupation with scientific analysis”; his opposition to spontaneity and reveries, the “vogue of suggestion in art”; his attacks on “hypnosis for the sake of hypnosis, illusion for the sake of illusion”; his preference for the “ordered ethical imagination” as against “the anarchic imagination.”

All this bears a striking resemblance to some of the doctrines of Mayakovsky, Brick, Tretyakov, Meyerhold and Eisenstein. The difference lies in the purpose of this intellectual discipline. For Professor Babbit it is the instrument of extremely reactionary social aims. He despises not only the faith in humanitarian “love” (as symbolized by Rousseau) but also the faith in scientific progress illusion” that “because we are advancing rapidly in one direction we are advancing (as symbolized by Francis Bacon). He scorns the rapidly in all directions.” Though no two minds were ever further apart, he finds that Rousseau and Bacon are fundamentally alike because both denied “something more than nature,” both believed in “change, relativity, and endless motion”; and both thought that “mankind is progressing toward a Utopia,” to be achieved, according to Bacon, by the perfecting of machinery; according to Rousseau “by the cultivation of an all-embracing love.”

However else they may differ, then, More, Babbit and those younger writers who follow them agree in their hatred of social progress. “Thus Babbit, mixing his contempt for the sentimental bourgeois reformer with his revulsion for social change in general, attacks the “romanticist” who affirms “the natural goodness of man, transfers the blame for man’s shortcomings upon a vicious artificial society, and declares that man can reach perfectibility simply by tempering his egoism with universal pity.” Romanticism, he finds, distrusts the intellect and denies the will, believes in the “original spontaneous genius,” and under the guise of “humanitarianism” sympathizes with mankind in a lump.

Babbit, in contrast, finds man by nature indolent; he sees man torn by a “real civil war between his natural self and his human self for which society cannot be held responsible” The implication is an old one: men in the mass are poor not because there is anything wrong with the social structure but because of their personal limitations. A definite social attitude is also implied in Babbit’s sensible campaign to have the youth think and will, and to replace the “romanticist” by the “humanist” who expresses “not his unique accidental self but the self that is common to him and all other men.”

But here we must raise the question: What is the “common self” of all men? Has it no connection with the “artificial society” in which men live? Do social classes play no role? Whose thought and will is being considered, and toward what end this thinking and willing?

Babbit lays his cards on the table in Democracy and Leadership. Here he attempts to solve several contemporary political problems, and in confusion clings to the apron-strings of religion. Nevertheless, he is certain of a few things: he knows, for example, that Karl Marx was wrong in “identifying work with value,” when, as “everybody” knows, this is determined by the law of supply and demand and by competition.”

Lest some reader might think that Professor Babbit teaches in Zanzibar it should be made clear that Harvard University is located in the United States, a country with the biggest trusts in the world which have succeeded tolerably well in regulating the “laws” of supply and demand and competition. But perhaps it is good for Professor Babbit to forget where he is living, for he is all in favor of “competition.” He even knows that the attempt to “eliminate competition has resulted in Russia in a ruthless despotism, on the one hand, and a degrading servitude on the other.”

The aim of Babbit’s thought and will becomes visible. “Thinking” and “willing” have been the prerogatives of leaders, and Babbit has something to say about leaders—especially bad leaders. He is, in fact, a connoisseur of leaders, for he urges us to note “a difference between the bad leadership of the past and that of the modern revolutionary era. The leaders of the past have most frequently been bad in the violation of the principles they professed; whereas it is when a Robespierre or a Lenin sets out to apply his principles that the man who is interested in the survival of civilization has reason to tremble.”

THE IDEOLOGY OF FASCISM

The aim, then, is to stifle “romanticism,” destroy the belief in human progress as symbolized by Rousseau, Francis Bacon, Karl Marx, Robespierre and Lenin, steel the intellect and the will toward fascism.

And this is no mere deduction from Babbit’s general point of view; he states his politics explicitly. “The time may come, he says in Democracy and Leadership, “with the growth of a false liberalism, when a predominant ballot-box and representative government, of constitutional limitations and judicial control, will display a growing eagerness for direct action. This is the propitious moment for the imperialistic leader. “Though the triumph of any type of imperialistic leader is a disaster, especially in a country like our own, that has known the blessings of liberty under the law, nevertheless there is a choice even here. Circumstances may arise when we may esteem ourselves fortunate if we get the American equivalent of Mussolini; he may be needed to save us from the American equivalent of Lenin…”

This may appear a long way off from literature, but so much is clear: those members of the younger generation of writers who recognize More and Babbit as the “two most mature intellects in American letters,” differ from the Wilsonian group in refusing to divorce literature from politics. Consciously or unconsciously they, like Marinetti and his followers in Italy, are creating an aesthetic fig-leaf for the politics of fascism. It is difficult to say how many of the younger writers share the social attitude expressed by More and Babbit; but Munson, at any rate, makes the logical literary deductions. Commenting on Vachel Lindsay’s poetry, he finds it a “bad fallacy” to expect a cultural renaissance “from below up”; on the contrary, he looks for it to come “from above down.”

No one has faith, Munson says, that “the Australian bushman or the Negritos in the Philippines will give the impulses toward cultural florescence, but nevertheless many do talk about such impulses rising from the soil of the proletariat…History instructs otherwise. The forming and regenerating impulse appears to come from a leader of great personal development and his band of specially trained followers.”

The great-man theory of history could not be stated more crudely by Mussolini himself. Yet what have these new literary “leaders” to offer us? Munson, despite his avowed contempt for the “romanticism” and “humanitarianism” of the Wilsonian group, simply drains their bitter despair to the last drop. He says:

“Dreiser has given us the youth who perceives that nature is ruthless, unsentimental, and society revealed as a scramble for power, with the rewards, money and women, going to the crafty and strong…Sherwood Anderson carried the symbol further. His youth attained the rewards of such a struggle, but then revolted against the material fixities of life. They were insufficient and more than a little sordid. Something was not satisfied, and his protagonist turned his back on them, turned groper for other values…Is it not possible to carry this symbol still further, until we reach the man who has lost his illusions concerning wealth and sex and art and social reform?”

Such an utterly negative “program” rejects the very foundations of life, and suits either despair or boredom. It may be a “remedy” for people who are impoverished in every way and have lost all hope of ever attaining “wealth and sex and art and social reform”; or for people who have all the wealth and sex and art they want, consider society beyond improvement and play with the notion of “perfecting the individual” in some vague “humanistic” manner.

THE LEFT-WING WRITERS

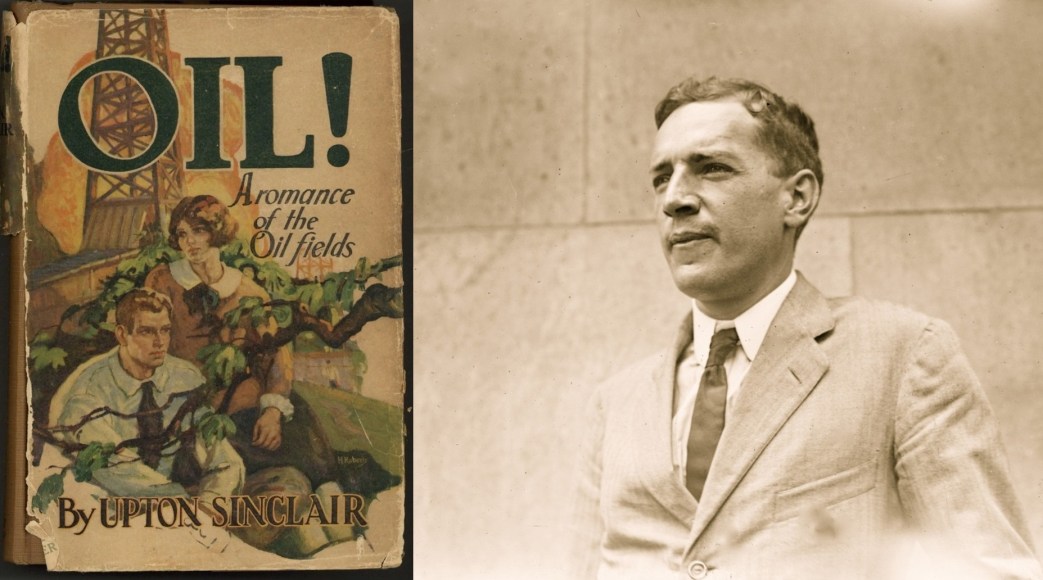

The left wing of American literature, like the right, has passed through some notable changes. The generation which was at its zenith in the Wilsonian period, continues to develop along its established lines. Upton Sinclair, the only living American author with a reputation, who has written novels of working-class life, is still vigorously turning out books. He continues to be the only socialist novelist in this country of any consequence. His collected works make an imposing list and include some great pamphleteering. The suppression of his novel Oil by the Boston authorities brought him back into the literary limelight from which the critics had banished him because he is only a “propagandist.” Oil has been praised now even by the bourgeois critics, one of the most conservative of whom compared it to Balzac’s work; and those American workers who read belles lettres consider it one of their few classics. The same is true of his new novel Boston.

The discussion which these books aroused afforded Sinclair an opportunity to clarify his social philosophy. To one critic who said Sinclair had accepted the Marxian formula at twenty-five and then stopped thinking, he replied: “I don’t think I ever called myself a Marxian and I have changed my views so frequently that my socialist comrades consider me very unreliable. What I accepted at twenty-five was not the Marxian dogma, but the general idea that the reconstruction of capitalist society will be done by the revolutionary workers. That idea was not Marx’s property, nor my own, but the collective wisdom of the workers’ movement for a century.”

Sinclair has been writing for twenty-five years; his work therefore has found its mould and at present reveals no new trends. The same may be said of Floyd Dell, who continues to write novels of family life and the development of sensitive individuals thrown on the periphery of society.

Of the younger men, only one has written a novel dealing with working-class life. He is W.H. Hedges, the author of Dan Minturn. This is the story of a labor leader caught in a conflict between his class loyalty and his love for a millionaire’s daughter.

Michael Gold, the best known of the younger writers attached to the working class, has published a collection of short stories entitled The Damned Agitator. He has since written two plays, La Fiesta, dealing with the Mexican agrarian revolution; and Hoboken Blues, dealing with Harlem.

Most of the other left-wing writers are writing either verse or criticism. The two most ambitious ventures have been the publication of the New Masses and the founding of the New Playwrights Theatre. V.F. Calverton’s magazine The Modern Quarterly, published in Baltimore, also counts itself with the left wing, politically.

It is an unfortunate fact that the left wing coheres loosely and that its thinking is vague. Only three American authors have published books of criticism attempting to give a social—sometimes even a socialistic—interpretation of literature. Upton Sinclair, who wrote an economic interpretation in Mammonart and Money Writes, is mechanical and literal in his judgments. Thus he rejects Goethe because he tipped his hat to a prince, and Dostoievsky because he (Sinclair) found The Brothers Karamazoff disgusting and was unable to finish it. In Money Writes Sinclair contracts his concepts so that the “economic” interpretation of literature means literally that poets and novelists sell their pens consciously for money, instead of being at the same time genuine products of a given social and intellectual milieu.

Floyd Dell’s Intellectual Vagabondage is more flexible in its interpretation, but narrower in range, and while it is more human than Sinclair’s, it is too subjective to serve as a critical instrument.

There remains V.F. Calverton, who has developed his viewpoint on literature in two critical works, The Newer Spirit and Sex and Literature. In these he attempts to relate literary productions to their social background. Like the rest of the left group, Calverton has been influenced by the October Revolution. I quote some passages from a “new critical manifesto” which he issued last year, and which will indicate the trend of his thinking:

“Our age,” the manifesto declares, “is one of change and revolution. We are at the dawn of either a great catastrophe or a great renaissance…The appalling signs of decay fence in our vision in every latitude. Our social and philosophic literature has already begun the swan song of our era.”

After a lengthy description of the imperialist epoch, the manifesto continues:

“Only a social revolution which will end this anarchy and competition can save our century from the devastating chaos that threatens it. To many, Russia is the signal of hope. There the greatest, most dramatic, most sweeping revolution of our age has been effected. A whole new culture is in the active, dynamic process of evolution. Its face is turned toward a new future. Despite concession and compromise, its new economics, new education, new art, new social life have burst upon an outworn civilization like a luminous aerolite upon the dark…In the struggle against the social adversity that confronts us, a new attitude is slowly penetrating into the spirit of our age. It is the growth of this attitude that will fortify our generation for its great task. This attitude is a new realism, a tough-minded, skin-bared approach to life that is defiant of sentimentality and idealism. It abhors euphemism and circumlocution. Its aim is directness and expedition. It is impatient of delay and contemptuous of evasion…It is radical; it is revolutionary…The nineteenth century with its poetry of hope and philosophy of progress was an age of ideals. The new age we may call the IDEAL-LESS AGE…It was the aftermath of the World War that plunged us into the Ideal-less Age. What do we mean by the Ideal-less Age? As part of the Ideal-less Age we have discarded first of all rhetoric and exclamation. We have scorned into silence the cry of ideals such as love, truth, justice…We have become sick of preachments and abstractions, skeptical of word and gesture. Through idealism men have been tricked by phrase and ruined by aspiration. We on the other hand shall be realistic.”

Here we find a few points of resemblance with Munson, for Calverton, like the politically conservative critic, is concerned about “our century” and “our generation,” without emphasizing the social gulf, for example, between the striking Pennsylvania miners and the investors of the Pittsburgh Coal Company, who happen to belong to the same century and generation. His formulation of the contempt for “love, truth and justice” is sufficiently abstract to tally with the similar contempt of Munson, as is his abstract scorn for ideals. He differs from the conservative critic, however, in his faith that a change in the social structure will save humanity.

“Those of the Ideal-less Age,” the manifesto continues, “talk not of love but of social conditions, not of peace but of economic reconstruction…They organize trade unions and not ethical clubs, teach science and not superstition, discuss economics and not religion.”

Passing to the positive side of his program, Calverton proposes a “social art which will meet its summation in the form of social beauty…Ever since the sweep of the commercial and industrial revolutions and the progress of individualist enterprise, art has become a thing of individual emotions and ideas. Its universality of approach has been largely sacrificed. Today with the growth of collectivist production, a new attitude, reminiscent of the mediaeval, is gradually beginning to crystalize.”

As an example of collectivist art Calverton points to Mayakovsky’s 150,000,000 and to the Soviet film Armored Cruiser Potemkin. With so unstable a critical foundation it is hardly any wonder that he includes among the examples of the new “social art” not only Soviet authors of all sorts of conflicting schools and tendencies, but works as diverse and often antagonistic in spirit as Ernst Toller’s Massemensch and Maschinenstuermer; Franz Werfel’s Goat Song, and Juarez and Maximilian; Upton Sinclair’s Singing Jailbirds and Eugene O’Neill’s Hairy Ape.

Perhaps even in this critical manifesto, which Calverton calls “our revolutionary declaration,” it may be possible to detect if not a note of despair at least of confusion; for after all, this is not an ideal-less age; on the contrary, as far as ideals realizable on earth go, no age has been as rich in “ideals” as this one. It is possible to define an “ideal” as the projection of class aims into an imaginary future. The most secret personal “ideals” would come under this definition, too, for private ambitions and aspirations have their roots in the standards of the class in which a man has his being. In this sense, we may say that our age is marked by two colossal social “ideals:”

Fascism, or the utmost imaginable power for the imperialist bourgeoisie; and Communism or the utmost imaginable freedom for the mass of humanity.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v07n08-aug-1928-communist.pdf

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v07n09-sep-1928-communist.pdf