Veteran Michigan activist Oakley C. Johnson analyzes a defining movement of the Great Depression, the Hunger March to Henry Ford’s Deaborn, Michigan factories demanding relief for the unemployed and destitute ending in a massacre. The March 7, 1932 demonstration on a cold Michigan day saw the murder of five workers. Joe York, George Bussell, Coleman Leny and Joe Blasio were shot by the Dearborn Police Department and Henry Ford’s gun thugs led by Harry Bennett. Five months later, Curtis Williams would also die of his injuries.

‘After the Dearborn Massacre’ by Oakley C. Johnson from The Daily Worker. Vol. 9. No. 76. March 31, 1932.

DESPITE the first stories issued to the press by the police, the testimony now seems to show that the 3,000 demonstrators in the mass parade to the Ford Motor Company plant were unarmed, and that the Dearborn and Ford police, using not only revolvers but a machine gun, fired at them unnecessarily, even after the crowd had begun to turn back. Already the Civil Liberties Union is taking a hand in the case; the families of the victims are planning to institute civil suits against Henry Ford and the Ford Motor Company; all the “rioters” who were under arrest have been released without being required to give bond; public opinion, particularly in Detroit itself, is largely against Ford; the city administration blames Ford’s own policies, and the repressive policies of the Dearborn administration, for the tragic outcome.

Briefly stated, the following appears to be substantially what occurred:

About 3,0000 participants in an unemployed demonstration on Monday, March 7, marched with police permission along Fort Street from downtown Detroit to the Dearborn city limits. They were walking in orderly formation, four abreast, singing or joking, carrying banners. A few hundred women were among them. They stopped just before reaching Dearborn and were addressed by Alfred Goetz, who instructed them to remain orderly, to use no violence and to maintain “proletarian discipline.” At the Dearborn limits they turned into Miller Road and were met by about fifty Dearborn police, who ordered them to turn back. No parade permit had been issued in Dearborn, in accordance with local policy toward radical demonstrations, although in Detroit the permit, under Murphy’s liberal policy had been freely granted. The marchers insisted on going ahead. The police threw teargas bombs, using up, according to one report, teargas worth $1,750. Maddened by the gas, the crowd picked up stones and threw them at the police. The police retreated, made another stand, retreated again. Finally the police used their guns, killing one and wounding some others. Then Harry H. Bennett, chief of Ford’s private police, drove his car into the crowd and fired either his revolver or his teargas gun at the demonstrators. He was hit by a rock, and was taken back toward factory gate number three by the police, who then, in conjunction with plainclothes men in Ford’s employ, opened up with their revolvers, wounding others. The crowd, several hundred feet from the gate, were then on the point of retreating, when the police and plain-clothes men opened fire again with a machine gun, killing three more and wounding over a score. The crowd broke and ran. The workers carried off some of their wounded fellow marchers, leaving the dead and others of the wounded lying in the road.

A score or so were arrested, and the wounded, taken to the Receiving Hospital and to other hospitals for treatment, were placed under technical arrest and chained to their beds. Maurice Sugar, attorney retained by the International Labor Defense for the arrested men, obtained their release on writs of habeas corpus.

On Friday night the Communists held an immense meeting in Arena Gardens, undisturbed by the police. Nearly six thousand people packed the hall and there were several speakers, including Biedenkapp of New York, and Alfred Goetz, one of the five men the authorities are supposed to be looking for. The police made no attempt to arrest Goetz. The meeting was in preparation for the funeral scheduled for the next day.

At Ferry Hall on Saturday afternoon the bodies lay in state. Above the coffins, against the wall, hung a huge red banner bearing a picture of Lenin. On one side was the motto, “Ford Gave Bullets for Bread,” and on the other “Police Bullets Killed Them.” Red roses were banked in front of the coffins. The band played the Russian funeral march of 1905. Rudolph Baker, Communist district organizer, in a brief address spoke of the lives of Joe York, Joe Bussell, Joe De Blasio and Coleman Lenz–York had worked in Ohio coal mines, seventeen-year-old Bussell had planned to go to the Soviet Union–and declared, “In the name of the district committee of the Communist party of Detroit, we lay the blame for these murders directly upon the shoulders of Henry Ford and Mayor Murphy.”

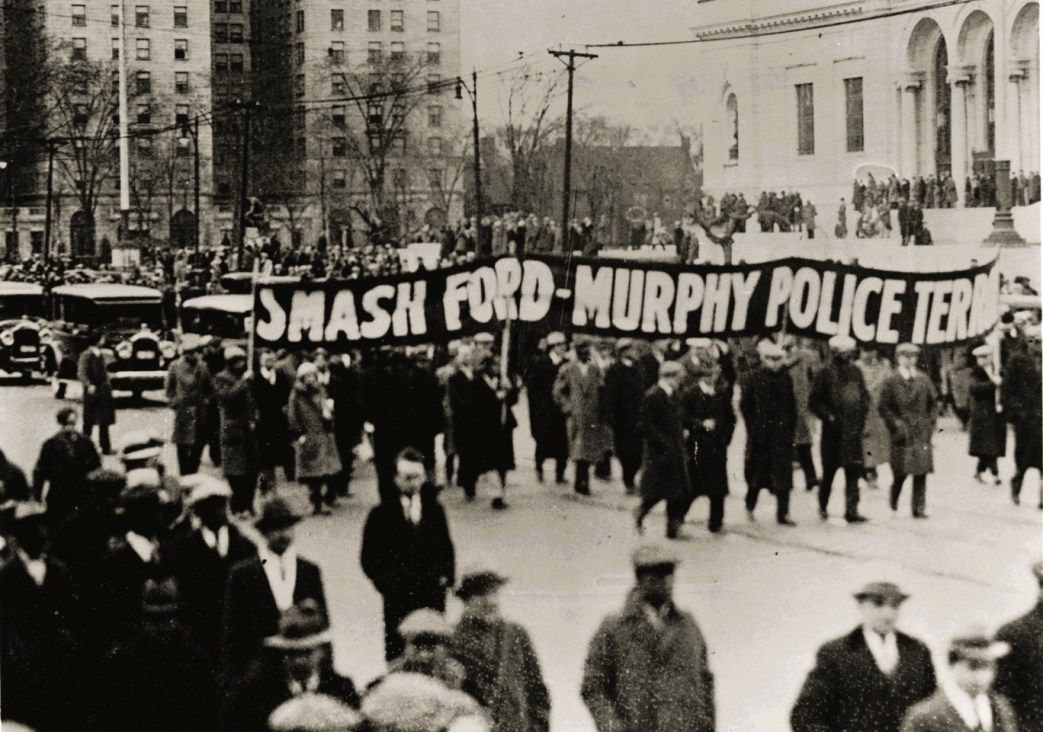

At Grand Circus Park, an hour later, from the thirteenth floor of Eaton Tower, I watched the parade move down Woodward Avenue. Witnessed by several thousand spectators, the procession came slowly toward Grand Circus Park, the band in front playing the “Internationale,” a massed square of workers carrying a huge red banner with the slogan in white letters, “Smash the Ford-Murphy Police Terror.” The funeral cortege of a score of automobiles came next, and after it, as far as I could see up Woodward Avenue, workers in mass formation, carrying banners. At least 20,000 must have participated. According to The Detroit Times, a total of 30,000 gathered at Grand Circus Park.

The police had cleared all traffic off Woodward Avenue. For two hours no wheel moved on that street except those in the parade. The roars of the crowd, cheering their speakers and booing the police, arose in waves to the window at which I watched. The crowd divided, some remaining in the park to listen to speeches, others packing into the five hundred automobiles which drove up, like a huge Ford belt line, to carry the marchers to the cemetery.

It was bitter cold, but the late sun shone on the tall silvered smokestacks of Ford’s River Rouge plant, the smokestacks glistening against the sky like a huge pipe organ. Directly adjoining the road that passes the Ford factory, on the extreme edge of Woodmere Cemetery, a lot had been purchased. Here in one grave the bodies were buried, and here, it was announced, within sight of the Ford Factory, not far from where the men had been shot to death, a monument would be erected, bearing an inscription to commemorate the manner of their killing. In three successive interviews in his office, Mayor Murphy assured me that free speech and free assemblage would be guaranteed in Detroit while he was mayor. “We don’t ordinarily require Communists to get a permit,” he declared. In most cases they need only serve notice and there will be no interference.” He said that while he had no wish to criticize the Dearborn administration, he believed that if they had had similar policy in regard to radical demonstrations, the tragedy would not have occurred. “In Detroit,” he said, “mass meetings and parades are held as a matter of right–police merely supervise and regulate.” Further, all groups have been welcomed regularly at the City Hall compose their grievances of petition for redress.”

In the killings at the Ford plant, he maintained, “the Detroit police and the Detroit policy were not involved…The entire conflict was between the Dearborn police, the Ford police and the demonstrators.”

Police Commissioner John K. Watkins, who is a former Rhodes scholar, confirmed Mayor Murphy’s statements.

“You consider the privilege of demonstrating and holding public mass meetings of a municipal right in Detroit, don’t you?” he was asked.

“Not only a municipal right, but a constitutional right, both state and national,” the police commissioner replied.

It happens that the Ford-Dearborn police policy is directly opposed to Mayor Murphy’s, and at the last election Ford’s candidate, John Lodge, was defeated by Murphy. Ford’s factory is outside the city limits. He does not pay a cent of taxes to the city. Though Detroit has extended its territory in all directions, and is beginning to encircle Dearborn, Ford has steadily resisted the incorporation of Dearborn into the city of Detroit. He steadily refuses, it is said, to contribute to the City Welfare Department, although thousands of his former employees are dependent upon the Department for aid. Clyde Ford, the mayor of Dearborn, is a relative of Henry Ford’s and owns a Ford agency. Henry Ford’s frequent announcements that he is going to “open up,” hire thousands more men, start prosperity going again, “risk all” in an effort to end the depression, and so forth–announcements which he does not carry out and apparently does not intend to–anger Detroit middle-class residents and business men, particularly since such announcements keep unemployed men pouring into Detroit seeking jobs which do not exist.

The majority of Detroiters support Murphy and hate Ford. Barbers, waitresses, clerks, most white-collar workers–not radical in any sense–say such things as, “I wish they’d tear down his whole factory. Maybe that would give the unemployed a job, building it up again.”

Murphy is backed solidly by the American Federation of Labor, by the Negroes because of his fairness as a judge in the trial some years ago of a Negro who defended his house against a mob and was tried for manslaughter, by the Catholic vote (after all, Murphy is Irish), and by a considerable proportion of the liberals, who remember in particular his post-war campaign against the war profiteers. Moreover, Murphy is ambitious. He is an old-fashioned Jeffersonian Democrat with modern political astuteness who is not above political maneuvering for his own ends. Here is his chance. The fight against Ford, if Murphy has the courage to take it up, will make an issue upon which he might climb far above the mayoralty of Detroit.

In this situation, however, Murphy is attacked very nearly as much as Ford. The world thinks of the Ford industries as being in Detroit, and of Frank Murphy, the mayor, as officially responsible. During the half hour that I sat in the mayor’s office on Saturday, his secretary collected the telegrams that had arrived during the preceding few hours and I looked them over. Fourteen protests had come in that morning from various organizations and meetings condemning the murders. There was a telegram from the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union of Chicago, another from the Y.C.L. of Negaunee, Michigan, another from a branch of the International Workers’ Order located somewhere in New York, another, a long resolution adopted at a mass meeting, from students and teachers in the Columbia Social Problems Club. The latter, referring to the fact of industrial depression and the peaceful nature of the unemployed demonstration at which the shooting occurred, declared that “the blame for this ruthless terrorism rests squarely upon the shoulders of Henry Ford and the municipal government of Detroit.”

To a man like Frank Murphy, these things burn. He sent a long telegram to The Young Worker, organ of the Young Communist League. The League had bitterly protested the murder because three of the dead were members of the organization. The telegram was published on the front page of The Young Worker with a list of sharp and pertinent questions for Murphy to answer.

And, after all, Murphy, despite the fact that his city probably provides more freedom of speech than any other in the country, does have things to answer, or at least explain. He does not, probably, expect Communist support in his administration–after all, he favors a retention of capitalism, however much he would like to remove some of its features–but he does want them to let him alone. When telegrams continue to pour in and the demonstrators continue to link his name with Ford’s–“the Ford-Murphy Police Terror” he asks, plaintively, “How can they do this to me?”

It is not his fault, of course, that the Wayne County Council of the American Legion in the Detroit district secretly passed a resolution introduced by Leonard Coyne, an attorney, on the Ford “riot,” saying, “we tender to the Ford Motor Company and other Wayne County industries the assistance of our organization and I pledge them the support of all members in any further emergency.” But it shows a situation which interpenetrates official Detroit. Miles N. Culehan, one of the assistant prosecutors in charge of the grand-jury investigation and an ex-service man, said in an interview with me and another journalist, “I don’t care who knows it, but I say I wish they’d killed a few more of those damned rioters.”

Furthermore, Hugh Quinn and three other Detroit detectives were present throughout the affair, and in the first edition of The Detroit Free Press Quinn is quoted as saying that Harry Bennett shot a man during the riot. But afterward, when quizzed severely by Murphy, Quinn denied everything, claiming that his presence in Dearborn was accidental and that he saw only stones flying in the air. Several raids on Communist Party and Trade Union Unity League headquarters were carried out during the next two or three days after the riot and some of these were made by Detroit police. This is explained on the ground that in Detroit the municipal police serve warrants issued by county officers not under the mayor’s control (an explanation much weakened, however, by the fact that in at least one raid the police had no warrant).

More damaging to the mayor’s claims are certain actions of the Detroit police reported by four injured demonstrators who were treated in hospitals: Robert Dorn, Harry Cruden, Eugene Macks and David Grey, young men varying in age from nineteen to twenty-seven. Grey was injured by a shot which grazed his scalp, but he was able to get away by himself and was treated by a private physician. The next day, his head bandaged, he was arrested in a restaurant by a Detroit policeman, taken to police headquarters in Detroit, finger-printed, then turned over to Dearborn police, who finger-printed him again and kept him in jail a night before he was released. The cases of the other three are all similar. They were wounded by the firing, were taken to the Receiving Hospital for treatment, but under what is called “technical arrest”. That is to say, they were handcuffed and chained to their beds during their stay in the hospital from Monday night till Friday afternoon. Under the terms of the writ of habeas corpus obtained by Maurice Sugar on Wednesday, all arrested persons were supposed to be released without charges and without bond not later than Thursday. These three were taken from the hospital Friday–and instead of being released were taken to Detroit police headquarters and fingerprinted. Then the Dearborn police were called, and the patrol took them to the Dearborn jail where all three were fingerprinted again, photographed, then placed in cells and with no charges against them were detained for four days, when they were released.

It was this many-sided and frequently obscure interworking of the Detroit police with the Dearborn police, as well as the desperate condition of the unemployed generally, against which the Communist delegation of fourteen, headed by George Kristalsky, protested vigorously when they appeared on Monday, March 14–one week after the massacre–before the Detroit Council and the mayor.

Meanwhile new machine guns have been purchased for the Dearborn police, and papers carry announcements that any other attempts at demonstrations will be met with guns.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1932/v09-n076-NY-mar-30-1932-DW-LOC.pdf