One of the few Southern states with an early labor union presence, Alabama saw the U.M.W.A. successfully organize Black and white miners together in the 1890s. And then the reaction. William Mailly, a former Alabama miner blacklisted for his union activity, revisits his former home fifteen years later, and in the aftermath of the Banner Mine explosion in which 128 miners were killed, over seventy of them Black convicts in forced leased-labor.

‘Alabama–A Slave State’ by William Mailly from Coming Nation. No. 43. July 11, 1911.

“ALABAMA is a slave state. There isn’t one of us miners but is in slavery. The capitalists have not only smashed our organization, they have made it impossible for us to reorganize. We’re watched and spied upon every moment of our lives. We’re afraid to talk to each other, and we dare not trust our oldest friends and nearest neighbors. Slavery is no word for it.”

It was an old miner, a staunch trade unionist all his life, that said this to me. And it was all true. Capitalism is in absolute, almost undisputed control in the district, where, with Birmingham as the center, efforts are being made to build up another Pittsburg that will rival the Northern city in everything, including its vile labor conditions. To this end all else is being sacrificed so that investing capital can have free rein and the fever for industrial development which permeates the whole South can vent itself. At all hazards, industrial development must go forward, and in their warfare upon organized labor, therefore, the corporations have always had the active, whole-hearted support of the political machinery of the cities, counties and state, which machinery, of course, is in the hands of the Democratic party.

When, after an absence of fifteen years, I visited Birmingham a couple of months ago, and announced my intention of visiting the mining camps to see old friends, I was warned to be careful in doing so and not get myself or any of the miners into trouble. I thought this was a joke at first, but I soon learned that it wasn’t and that I was liable at any time to be made to feel unwelcome at any place I visited. And it required one to go out into the mining camps to learn how bad conditions are.

No miner can have anyone visit him from the outside without having to give an account of the visitor. The companies have at each camp hired guards who patrol the camps and meet the trains as they arrive. If a stranger gets off the train he is usually accosted by one of the guards, asked his name, where he lives and what his business is in camp, or he is followed and watched openly in all his movements. If he goes to a miner’s house, the miner has to explain to the satisfaction of the company or get out. Sometimes the miner is not given a chance to explain and is told to get out anyway. The company takes no chances. The most rigid watch is kept on the men for fear they may make a move to organize.

The Curse of the Company Store

The company store flourishes in all its profitable glory. No miner who does not trade in a company store can work anywhere. Indeed, there is rarely any other store for him to trade in, unless he can go into the city, and he can seldom save up enough to do that; the company store gobbles up his wages as he makes it. The independent stores around the mines have nearly all been driven out of business by the company stores and the few that remain have but a precarious existence.

Even the farmers, who are proclaimed by the Southern political orators in all seasons, and especially at campaign time, to constitute the backbone of the nation’s manhood and prosperity, even they have been made to feel the iron heel of the oppressor. Once they did a thriving business peddling their products through the camps among the miners, but now they have lost their former customers, because the miners are prohibited from buying of them. So the farmers now sell direct to the companies at the various local stores and the companies obligingly set their own prices and dictate terms to the farmers.

There have been other changes. In the old days, when I worked in the mines of Alabama, there was hardly a house but was kept clean and in good order and had its little garden when the springtime came, and these gardens were cultivated by the miners and their wives. The camps looked fairly neat and bright and wholesome as a consequence. But now, where before there were rows of potatoes, cabbages, peas and other vegetables, weeds are growing abundantly, the fences are either broken down or gone entirely and the horses are dirty and dilapidated beyond the power of words adequately to describe. And this change has come about because the miners’ gardens interfere with trade at the company stores and the miners are forced to depend for whatever vegetables they need upon the company stores and them alone.

And the people in the camps have changed also. Of all those who came from the North years ago and who furnished the skilled labor that made it possible for the mines to be opened at all, only a few remain. Gradually they have been weeded out to make room for the negro and native white who has come in off the farm, attracted by the fairy stories of the “big money” the miners were making. Successive strikes and lockouts have seen importations of strike breakers from the cotton fields and Southern city slums and the farms, until the pioneer miners from the North have been scattered, many of them returning back whence they came or going where they could have more freedom and work under organized conditions.

Cheating in Weight

There are no longer checkweighmen on the mine tipples employed by the miners themselves to see that their coal is weighed and credited to them correctly. Now the company weighmen can do as the company pleases and the better he does it the longer he will hold his job. As a result, cars containing two tons of coal of 4,000 pounds, are usually credited to the miner at 2,500 or 2,700 pounds, or he is, docked for “dirty coal”–that is, when his car is said to contain too much slate or coal–and he has no redress. He will get paid for only what appears against his number on the tally sheet.

There is also the contract system, which has become one of the greatest evils. Under this system, a miner contracts to get out the coal on a certain entry for a fixed price per ton, usually the prevailing rate, and employs others to dig the coal, either negroes or Italians (many of the latter have recently come into the state, and they work long, cheap and hard). The contractor is held responsible for conditions on his entry and he in turn pays those who work for him either a daily wage or a certain price per ton. These contractors are usually the more skilled and experienced miners remaining in the state, and the system is used by the companies both to keep down the expense of mine operation and to prevent the miners from having mutual interests that would bring them together.

And all these changes have come about within a few years. They have followed naturally upon the wiping out of the miners organization–for it is wiped out, and so effectually that hardly a vestige remains. Yes, there is a district office of the United Mine Workers in Birmingham, with district officers and all the paraphernalia of organization, but there is no organization, though the officers heroically make a brave front at it. The form is there, but the substance is missing. There is no secret about this, everyone knows it. The national organization keeps up the district office, in the hope of a revival of interest, sometime, somehow, but there is little warrant for such a hope. Even the most optimistic admit this.

Politics Play Part

For this state of affairs, the corporations have, first of all, the various state administrations, supported by those of the cities and counties, to be grateful to The Democratic party, without serious opposition for possession of the political machinery throughout the state, has always been in complete subserviency to capitalist interests. Only here and there is there a public official who has any sympathy for organized labor and he has to keep pretty quiet about it or the bosses will see that he is not renominated, which is equivalent to an election, or reappointed when a new administration comes in. On the other hand, very seldom are there any of the company thugs arrested for beating up or shooting a miner or other workman, and if he is, seldom is there any punishment meted out to him. The courts–all the legal machinery–are in the hands of the capitalists and they look after their own.

In all of the miners’ strikes that have occurred in Alabama during the past twenty years, the strikers have had solidly arrayed against them all the forces of government, backed by the press and the business element. To recite all this history in detail would take up too much space. I cannot do more than give a mere sketch that can only present a slight idea of what has occurred to place the miners of Alabama in the degraded condition they now are. And perhaps no body of miners in the United States have contended so bravely against adverse conditions to build up an organization and better their condition than have they. That they have failed has not been because of lack of courage, capacity for endurance and devotion to their cause.

The first state strike of miners took place in the winter of 1890. The issue was a demand for an increase of 5 cents per ton. The strike was inspired by the national miners’ union, then District 135 of the Knights of Labor, it was a short one and it was lost. It was not until 1893 that the miners attempted to organize again and that was brought about through the demand of the companies for a 25 per cent decrease in the scale. That was the panic year and the miners were ill-prepared for a strike, but they resisted the decrease and the companies were compelled to withdraw their demand.

But it was only for a while, until the companies could be in a better position to enforce it. The demand was renewed the following year, when the miners were believed to be down so low in the standard of living, after months of enforced semi-idleness and semi-starvation, that they could not longer resist it. But they did resist, for they, too, had been organizing. The final result was that a strike began in April, 1894, a week before the great national strike of miners headed by John McBride began. It was during this strike that the negro miners, who had acted as strike breakers in 1890, came out with the white men, and this marked the first concerted effort of the white and colored miners to act together for their mutual benefit. And ever since that the negroes have played a good part in the fight with their white brothers against the exactions of the companies.

Crushed by Military Force

The strike of 1894 was notable for the intensity and bitterness which marked its progress. It lasted five months and it had every indication of complete success, even up to the very last, notwithstanding that the state government conducted throughout an active campaign to break the strike. Thomas G. Jones was then governor of the state, and he was imbued with a fine frenzy of military ardor. He ordered the state troops to Ensley, near Birmingham, where he “commanded” them personally. The American Railway Union strike came on at the same time. Jones stationed a detachment of troops in the Union Depot in Birmingham, with mounted gatling guns, and he declared martial law in the city. Jones was a little despot for a while. Several times he summoned the union leaders before him and warned them what would happen to them if they persisted in their “lawless” course. He also headed a company of troops at night-time through several mining camps, where the strikers were quartered in log huts which they had erected after being ejected from the company houses, and there he had the huts searched by the soldiers for the “desperadoes” who inhabited them. The strike was settled on a compromise, but was practically lost. The adoption of a sliding scale by which the miners were paid per ton according to the price of iron in the market was claimed as a victory. The sliding scale, which sometimes went up, but more frequently slid downwards, no longer exists. There is no definite scale of wages now; the miners take what the companies give them.

About five years ago, President Roosevelt recognized former Governor Jones as a man after his own heart by appointing him United States Circuit Judge in Alabama and the decisions of Judge Jones since then have amply justified his appointment as a conscientious and faithful friend of the corporations of that state.

It was some time before the miners’ union recovered from the strike of 1894, but there was continual friction between the miners and operators until 1902, when the questions at issue were submitted to arbitration, Judge Gray of Delaware acting as presiding judge. The miners won almost every contention for which they pleaded before the arbitration board and obtained a new and better adjustment of wages and conditions. But the companies were not satisfied with the working out of the award, and in 1904 they asked for a reduction in wages that brought on a strike that was nearly a record-breaker for the length of time it lasted. When this strike started the miners’ organization was in the best condition of its entire history. was then part of the national organization with John Mitchell as president, and everybody working around the mines, including store and office clerks, and in some cases even mine foremen belonged to the union, the system of collecting dues through the company office assisting materially in bringing this about.

That strike lasted two years from 1904 to 1906–and cost the national organization over a million dollars in strike benefits and relief. It was a test of endurance between the companies and the men and the companies eventually won, for the strike was called off. Again the state government had done its share to bring about this result and the history of the strike is a long and black record of intimidation, assaults, arrests and misrepresentation on the part of the law administering powers, the press and the business people. The loss of that strike broke the back of the miners’ union in Alabama, the end that the operators had spent, and had been willing to spend, millions to accomplish. In 1908 the miners attempted to recover the ground lost. The national organization, with John L. Lewis, president, sent in organizers in an effort to reorganize the shattered forces. There was a strike for the recognition of the union and a return to the former union control of the mines. The national organization itself took charge of the strike and its representatives were active in the field. They met with a warm reception. They were driven out of every camp in the state at the point of guns and they were beaten with clubs and subjected, in several cases, to unspeakable indignities until they could find no rest or haven anywhere. They were denounced as “carpetbaggers” who had come from the North to batten on honest Southern labor and interfere with legitimate business enterprise.

The state government was again active. The governor this time was one B.B. Comer, owner of a cotton mill in Birmingham where children are employed at as low wages as possible and as young as the law allows–if not younger–and a highly respectable and very religious man. But Comer went Governor Jones one better. This time the strike only lasted two months, although the call was generally responded to throughout the state. Comer was even more advanced than Jones. He also took the field with the state troops and not only invaded the strikers’ camps, but had the soldiers cut down and destroy the tents which the strikers were sheltered in. The strike was lost, and since that time the miners’ organization has vanished from Alabama, smashed into smithereens by the combination of the corporations, the government, the press and the business people, who believe that industry should be kept running, whether the wages paid to the workers be good, bad, or indifferent.

It is significant that since the decline of the miners’ union the number of mine accidents in Alabama, through explosions and otherwise, has greatly increased. This is partly because there is no longer union control around the mines and also because most of the best skilled miners have left the gate, as I have previously pointed out. There are fewer competent foremen and efficient miners than there formerly were and the safer methods of mining have passed away. Now, instead of mining the coal, using chiefly skill and muscle, and black powder for blasting purposes, dynamite has come into general use, and this has increased the possibility of explosions and other accidents.

So frequent have these explosions become that a new mining law was enacted by the legislature last winter. The original bill was drafted by representatives of the coal companies. The provisions of the bill were so outrageously bad, however, that the miners’ union officials were able to make a fight against it and the bill was amended and some of the most objectionable features stricken out. While the law is admitted to be an improvement over the previous one, yet the companies have much the best of it and increased responsibility is placed upon the miners in various ways. The latter are skeptical as to whether the new law will effect anything better or not.

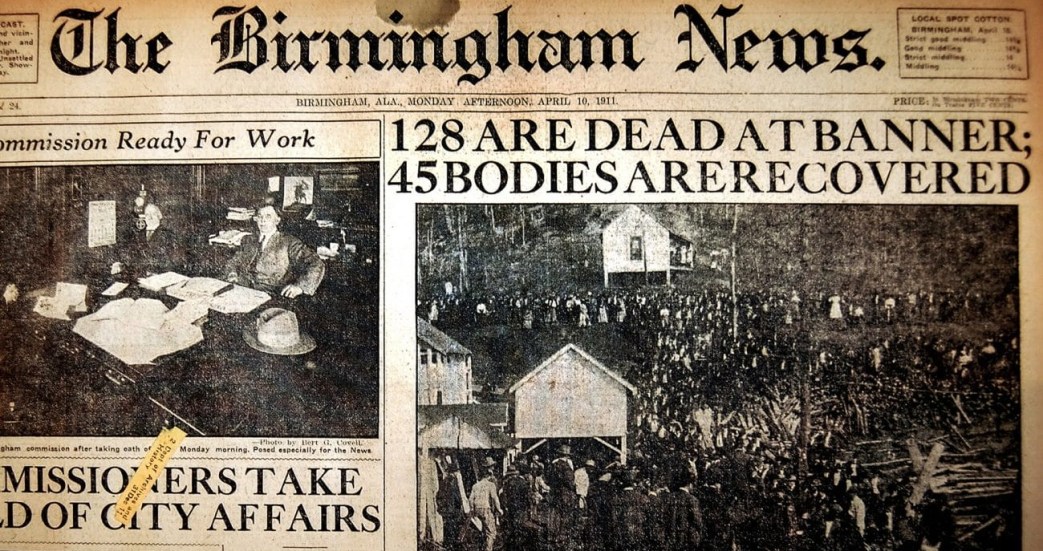

Then there is also the convict lease system, by which convicts are worked in mines in competition with the “free” miners. It was in a convict mine at Banner that the disaster occurred last April by which 125 men were killed, all except three or four being convicts. These convict mines are worked 310 days in the year and they have been very useful to the corporations in enabling them to supply the market with coal during strikes. The system stands as one effectual barrier against the organization of the miners of Alabama.

But not only the miners’ union has suffered. The entrance of the United States Steel Corporation into the Birmingham field, through the absorption of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company, has seen every branch of organized labor decline. There is not remaining a single lodge of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers in the entire district. The open shop prevails in every mill and furnace and that means that there is practically not a single union member working in them. Trade unionism generally was never in such a disorganized, demoralized condition.

Alabama is indeed a slave state. But what matters it so long as Capitalism reigns and the Democratic administration at Montgomery still lives?

The Coming Nation was a weekly publication by Appeal to Reason’s Julius Wayland and Fred D. Warren produced in Girard, Kansas. Edited by A.M. Simons and Charles Edward Russell, it was heavily illustrated with a decided focus on women and children.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/coming-nation/110708-comingnation-w043.pdf